Macrophytes (accessible version)

advertisement

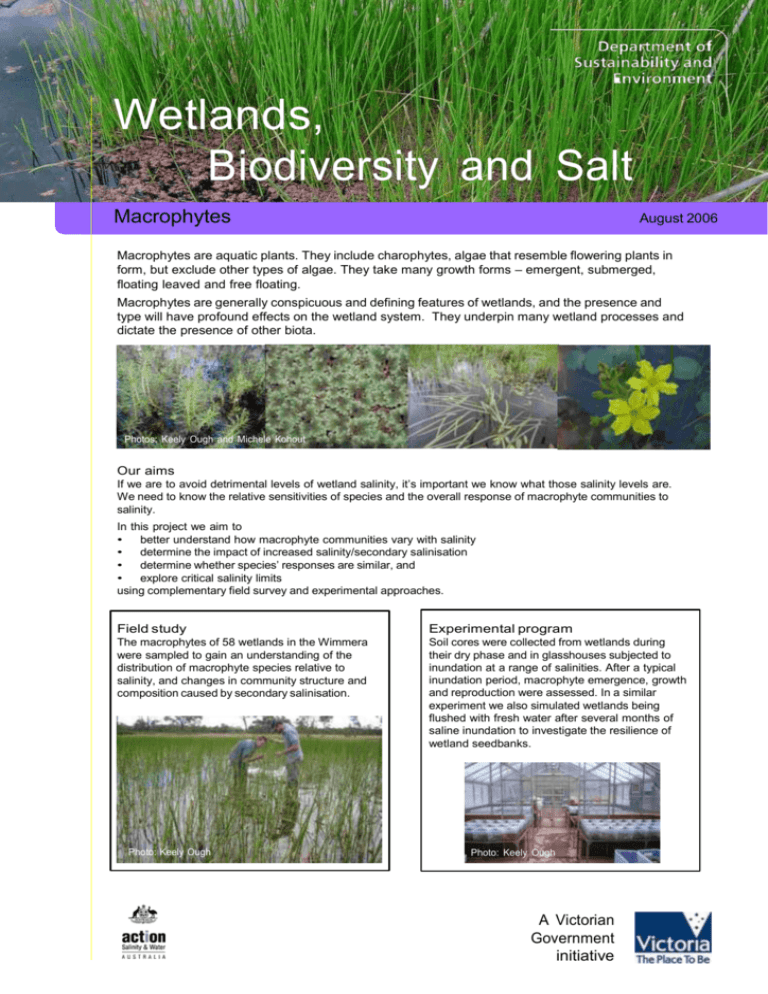

Wetlands, Biodiversity and Salt Macrophytes August 2006 Macrophytes are aquatic plants. They include charophytes, algae that resemble flowering plants in form, but exclude other types of algae. They take many growth forms – emergent, submerged, floating leaved and free floating. Macrophytes are generally conspicuous and defining features of wetlands, and the presence and type will have profound effects on the wetland system. They underpin many wetland processes and dictate the presence of other biota. Photos: Keely Ough and Michele Kohout Our aims If we are to avoid detrimental levels of wetland salinity, it’s important we know what those salinity levels are. We need to know the relative sensitivities of species and the overall response of macrophyte communities to salinity. In this project we aim to • better understand how macrophyte communities vary with salinity • determine the impact of increased salinity/secondary salinisation • determine whether species’ responses are similar, and • explore critical salinity limits using complementary field survey and experimental approaches. Field study Experimental program The macrophytes of 58 wetlands in the Wimmera were sampled to gain an understanding of the distribution of macrophyte species relative to salinity, and changes in community structure and composition caused by secondary salinisation. Soil cores were collected from wetlands during their dry phase and in glasshouses subjected to inundation at a range of salinities. After a typical inundation period, macrophyte emergence, growth and reproduction were assessed. In a similar experiment we also simulated wetlands being flushed with fresh water after several months of saline inundation to investigate the resilience of wetland seedbanks. Photo: Keely Ough Photo: Keely Ough A Victorian Government initiative Our results so far Both field and experimental data indicate that increased salinity leads to a • reduction in the abundance of macrophytes • decline in species richness, and • change in community structure. This will have flow-on effects to wetland function such as primary production, nutrient cycling and habitat provision. Critical levels of salinity No. of individuals Individual taxa show a range of responses to an increase in salinity, rather than all taxa declining at the same level of salinity. Increasing salinity Species response to salinity varied, from unaffected to very sensitive. For example we might wish to compute the salinity at which the number of emergents is reduced to say 50% of the optimum – Salinity Level 50 for emergence (SL50e). Or we could use any desired proportional response. These figures would allow comparisons between species, and between life history stages, and could represent critical levels of salinity that lead to response of a particular magnitude – somewhat analogous to LD50 figures used by toxicologists. We will do this over the coming months. Optimal No. of emergents We propose a useful procedure is to compute the salinity that decreases the number of plants (or biomass or reproductive capacity) to a given proportion of the modelled number at the salinity of optimal response. SL70e SL50e Increasing salinity Proposed critical salinity levels, which will allow comparison between species and life history stages, and could allow us to set wetland salinity maxima. Potential uses of relative sensitivity data This variation in species response could be used as a management tool, both in terms of determining how much salt is too much, and being better able to monitor the outcomes of increased levels of salinity. For example, to protect a particular wetland, the salinity could be kept below the critical level for a suite of the most sensitive taxa. These taxa then provide the basis for a targeted monitoring program, which would simplify measuring of the performance of programs designed to avoid or alleviate salinity. For rehabilitation programs, species would best be chosen from the least sensitive end of the spectrum, potentially saving money on the planting of salt sensitive taxa whose critical salinity levels have been exceeded. As more of our analyses are completed, we are building up a picture of the range of critical salinity levels important to the long-term maintenance of freshwater macrophyte communities. Published by the Victorian Government Department of Sustainability and EnvironmentMelbourne, August 2006 © The State of Victoria Department of Sustainability and Environment 2006 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Authorised by the Victorian Government, 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne. ISBN 1 74152 603 5 For more information contact the DSE Customer Service Centre 136 186 or Dr Michael Smith on (03) 9450 8612 or michael.smith@dse.vic.gov.au, Arthur Rylah Institute, Department of Sustainability and Environment, PO Box 137, Heidelberg 3084. This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. www.dse.vic.gov.au/ari/ the Wetlands, Biodiversity and Salt project can be found by following ‘Research Themes’ to ‘Salinity and Climate change’