Pre-Socratic Seminar Questions and Articles Packet

advertisement

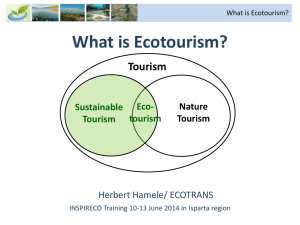

Name: ______________________ Class Period: ______ Socratic Seminar: Human Environment Interaction in Latin America 1. Read the following articles about various topics in Latin America a. Highlight key terms b. Underline important passages c. Write questions and comments in the margin 2. Answer the following questions: a. What are the reasons for blackouts in Brazil? b. Why is hydropower also a problem for Brazil? c. What is slash and burn agriculture? d. Describe TWO negatives of the practice. e. When was it used effectively and what was different then? f. Define infrastructure. g. What is ecotourism? h. What makes Latin America a perfect region for ecotourism? 1|Page 3. Create FIVE questions of your own (using Bloom’s Question Stems worksheet to help) to bring to the seminar. Write the questions below: 2|Page Power Quest: Brazil Works to Wipe "Blackout" From the Lexicon As Rio de Janeiro prepares to host the World Cup finals in 2014 and summer Olympics in 2016, pressure is rising to improve electric service there and throughout Brazil. For National Geographic News Published December 13, 2011 When the lights go out these days in Brazil, the one word that Energy Minister Edison Lobão doesn't want to hear is apagão, or "blackout." The word took on multiple meanings for citizens in the world's fifth largest nation after crippling power outages and government-mandated energy rationing in the early 2000s. Any massive failure of government or corporate officialdom-from plane delays to shortages of skilled workers-came to be branded as apagão. In last year's national elections, before Dilma Rousseff won the presidency in a runoff, there was vigorous dispute on Twitter over apagão, and which party had left more people in the dark most often. And last February, when 50 million people lost 3|Page electricity for hours in the impoverished northeast, Lobão said it should not be considered an apagão, but a "temporary interruption of the electricity supply." Keenly aware of domestic pressure over reliable electricity service, and knowing that the world will be watching as Brazil hosts both the World Cup and the Olympics within the next five years, public and private officials are working to bolster power delivery. But solutions are not easy in this sprawling country, South America's largest nation. While faced with feeding one of the world's largest cities, São Paulo, Brazil also is steward both to the Amazon and to more rural poor than any other nation in the Western Hemisphere. Brazil is roiled by conflict between city and village, development and preservation, as it considers how to fuel its economy and deliver future energy. Wide Reach, Many Complaints AES Eletropaulo, which serves 6.1 million customers in São Paulo and the 23 cities in the surrounding metropolitan region, has plenty of critics. Procon, São Paulo state's consumer protection agency, lists it every year as one of the companies that receives the most complaints. The agency says blackouts are occurring more often in the city. A judicial sentence that took effect in August against Eletropaulo, in a case brought by Procon after a nationwide blackout in 2009, established that for any blackout exceeding four hours, the company would be fined 500,000 Brazilian reais ($300,000) for each hour of power outage beyond the initial four. Despite frequent displeasure over outages, the reality is that electricity has wider reach in Brazil than any other public service, according to newly published figures from Brazil's census. The official records show the electric grid reaches up to 97.8 percent of homes throughout the country. In contrast, only 82.9 percent of homes have access to water supply, and just 67.1 percent of homes are hooked into public sanitation systems. Energy consultant Roberto Kishinami, a former adviser to Brazil's government, described how private multinational companies developed the first power plants around São Paulo city in the 1920s, tapping the power of the Tietê River to generate electricity. While powering the industrialization of São Paulo, they left treatment of sewage to the same river, causing an environmental and urban problem for decades. Kishinami says water resources were viewed as a public good, and entrepreneurial spirit was unleashed to advance electricity. But these were not accompanied by commitments to efficiency or environmental protection. Distribution of electricity is by no means equal across the country. In the poor northern states, including the Amazon, nearly one in each four rural homes still needs candlelight at night. But in São Paulo, only 1 in 2,000 homes lacks access to the power grid. As a result, more than 10 percent of Brazil's electricity is consumed in an area less than 1/1000th of the nation's size. The most frequent power shortages in Brazil are actually in the poor rural areas where electricity coverage is limited, and where cities are small and sparse. Nearly 30 percent of the 65 incidents registered in the first half of 2011 by the national grid operator ONS (National Operator of the System), occurred in the Amazonian states of Pará, Acre, and Rondonia. 4|Page "I have worked in the north of Brazil," says Otavio Grillo, operational director of AES Eletropaulo. "Sometimes, power lines have to extend for 400 kilometers [248 miles] in the jungle to reach the population," he says. That, according to him, increases the chances that environmental factors will interfere with the lines. (Related: "Amazon Opportunity: Brazil Doesn't Count on Carbon Market") Official data kept by Brazil's National Agency of Electric Energy (Aneel) shows that blackouts in São Paulo are less frequent than in rural areas. When blackouts happen in the city, though, they affect areas vital to Brazil's economy; São Paulo generates 15 percent of Brazil's GDP. "We have the most critical clients in Brazil," says Grillo. When power outages happen in the north of the country, few outside the affected region hear about it, like a tree falling in the Amazon. In São Paulo, due to the high concentration of energy consumers-more than 4,000 per square kilometer-any such disruption generates a swarm of complaints, making Eletropaulo's call center buzz. On the worst day, when a cyclone hit the city in July, there were 240,000 calls an hour. Eletropaulo issued a press statement that the outage should not be considered an apagão because only a few streets experienced outages. Goal: Better Service Pressure to improve the nation's electric service is expected to increase in the next five years, when Brazil's second-largest city, Rio de Janeiro-capital of state adjacent to São Paulo-hosts the finals of the 2014 FIFA World Cup and the summer Olympics in 2016. "Quero ver na Copa" has become a common remark when a Brazilian faces a lapse in any public service, including electrical: "I want to see what happens during the World Cup." Power upgrades are integrated with construction planning for the events. In the capital of Brasília, a substation is being built just to power the national stadium for the games. In Paraná, just south of São Paulo state, the state power company is investing 500,000 Brazilian reais ($269,500) to improve the system for faster response to outages. In Rio, served by the electric company, Light, authorities are pouring millions of dollars into revamping the decades-old underground electricity and gas utility infrastructure. Last summer, exploding manhole covers became epidemic in Rio as sparks from old transformer junctions ignited gases beneath the street. Eletropaulo says that since 2006 it has invested more than 3 billion Brazilian reais ($1.6 billion) in its network and it plans to invest a like amount before 2015 to improve services. This past summer, it announced a collaboration with General Electric and Trilliant to install smart meters and wireless communication to improve its electric delivery. Brazil's government has put an emphasis on new energy generation, focusing on the same kind of development that has served the nation in the past: Hydroelectric, which currently provides nearly 85 percent of the nation's power. Regulators at the Aneel are discussing how to privatize power generators in Brazil's north, which currently are enterprises administered by Brazil's staterun Eletrobras. (Most other power companies in the country-like AES Eletropaulo-were 5|Page auctioned away by the federal government in the late 1990s.) In the past five years, there have been ten auctions for licenses to build new power plants. Three of the new hydroelectric plants would be in the Amazon, tapping the energy potential of the Madeira and Xingu rivers. But one project, Belo Monte, threatens to displace native populations, causing the Organization of the American States in April to demand suspension of construction. Brazil's government criticized the OAS move, and president Rousseff suspended Brazil's payment of $800,000 to the organization in retaliation. Lobão once attacked critics of the Belo Monte project as "the demoniac forces that are pulling Brazil down." But the new hydro generation will only partially help address the electricity delivery problems that trouble Brazil's residents. Critics of Belo Monte are quick to point out that its power is likely to flow, at least in part, to new and growing industrial development. Brazil's giant mining company, Vale, and steelmaker Sinobras are shareholders in the consortium of government and private companies building Belo Monte. Hydropower Dependence But getting power from rivers to the cities and industry has often been a challenge in a nation that is more than 8.5 million square kilometers (3.3 million square miles) in size. This is true even though Brazil has what Kishinami describes as "a very robust interlinked system," a grid that covers the entire country, north to south, east to west. "Few countries as big as Brazil have the same kind of [interconnection]," said Kishinami. (In contrast, the United States has no interconnection between its east and west grids and Texas is isolated on its own grid.) In 2007, a blackout that left 3 million Brazilians in the dark was caused by accumulated soot in power line insulators. Such incidents are becoming less frequent, though. Aneel's official figures say the average Brazilian consumer loses power nearly 15 times a year, for a total of 18 hours, down from 21 times and 26 hours a year in 1998, when the agency was created. But the general interconnection can allow trouble to spread far and wide. That's what happened on November 10, 2009. After a triple failure in energy transmission circuits, 18 Brazilian states were in the dark for as long as seven hours. The entire neighboring country of Paraguay also faced a brief power shortage, because the two nations share the second-largest hydroelectric dam in the world, Itaipu on the Paraná River. In Rio de Janeiro state alone, the outage cost industries 1 billion Brazilian reais ($539 million). Officials blamed strong wind and lightning for the power failure, although researchers have disputed these findings. Since the final report on the incident found flaws in maintenance of the transmission lines, Aneel fined Furnas Centrais Elétricas, a private company that manages power distribution, 53.7 million Brazilian reais ($28.9 million) -one of the largest fines in the agency's history. It is not only the maintenance of the long transmission lines that is a problem, but the political tension that results from Brazil's decision to have power travel long distance from rivers in rural areas to its metropolitan centers in the south. Critics say the nation is both failing to serve the 6|Page power needs of its rural poor, and threatening the culture of the indigenous people who rely on the rivers. Kishinami believes that Brazil has focused on large hydroelectric projects to the exclusion of other energy alternatives, just as the building of roads has crowded out other transportation alternatives, such as trains and navigation by water. He believes Brazil should be spending more resources to explore technologies like biomass and solar energy to power rural communities. "Brazil has the challenge to incorporate new technologies to minimize environmental impact and make alternative energy an economic alternative," he said. In addition to "big solutions" in the interest of the nation, he said, "small solutions" need to be developed in the interest of communities. "We still don't have a planning system that's able to think in different scales and levels," he said. 7|Page Geography Slash and Burn Agriculture Slash and Burn Can Contribute to Environmental Problems By Colin Stief, Geography Intern A slash and burn fire burns in the Amazon rain forest. Stockbyte/Getty Images Slash and burn agriculture is the process of cutting down the vegetation in a particular plot of land, setting fire to the remaining foliage, and using the ashes to provide nutrients to the soil for use of planting food crops. The cleared area following slash and burn, also known as swidden, is used for a relatively short period of time, and then left alone for a longer period of time so that vegetation can grow again. For this reason, this type of agriculture is also known as shifting cultivation. Generally, the following steps are taken in slash and burn agriculture: 1. Prepare the field by cutting down vegetation; plants that provide food or timber may be left standing. 2. The downed vegetation is allowed to dry until just before the rainiest part of the year to ensure an effective burn. 3. The plot of land is burned to remove vegetation, drive away pests, and provide a burst of nutrients for planting. 4. Planting is done directly in the ashes left after the burn. Cultivation (the preparation of land for planting crops) on the plot is done for a few years, until the fertility of the formerly burned land is reduced. The plot is left alone for longer than it was cultivated, sometimes up to 10 or more years, to allow wild vegetation to grow on the plot of land. When vegetation has grown again, the slash and burn process may by repeated. 8|Page Geography of Slash and Burn Agriculture Places where open land for farming is not readily available because of dense vegetation are the places where slash and burn agriculture is practiced most often. These regions include central Africa, northern South America, and Southeast Asia, and typically within grasslands and rainforests1. Slash and burn is a method of agriculture2 primarily used by tribal communities for subsistence farming (farming to survive). Humans have practiced this method for about 12,000 years, ever since the transition known as the Neolithic Revolution, the time when humans stopped hunting and gathering and started to stay put and grow crops. Today, between 200 and 500 million people, or up to 7% of the world’s population, uses slash and burn agriculture. When used properly, slash and burn agriculture provides communities with a source of food and income. Slash and burn allows for people to farm in places where it usually is not possible because of dense vegetation, soil infertility, low soil nutrient content, uncontrollable pests, or other reasons. Negative Aspects of Slash and Burn Many critics claim that slash and burn agriculture contributes to a number of reoccurring problems specific to the environment. They include: Deforestation: When practiced by large populations, or when fields are not given sufficient time for vegetation to grow back, there is a temporary or permanent loss of forest cover. Erosion: When fields are slashed, burned, and cultivated next to each other in rapid succession, roots and temporary water storages are lost and unable to prevent nutrients from leaving the area permanently. Nutrient Loss: For the same reasons, fields may gradually lose the fertility they once had. The result may be desertification, a situation in which land is infertile and unable to support growth of any kind. Biodiversity Loss: When plots of land area cleared, the various plants and animals that lived there are swept away. If a particular area is the only one that holds a particular species, slashing and burning could result in extinction for that species. Because slash and burn agriculture is often practiced in tropical regions where biodiversity is extremely high, endangerment and extinction may be magnified. The negative aspects above are interconnected, and when one happens, typically another happens also. These issues may come about because of irresponsible practices of slash and burn agriculture by a large amount of people. Knowledge of the ecosystem of the area and agricultural skills could prove very helpful in the safe, sustainable use of slash and burn agriculture. 9|Page Lack of Airports Hinders Tourism Growth for Latin America Latin America must invest in airports The International Air Transport Association (IATA) yesterday called on governments and other actors in the industry in Latin America to invest in security and infrastructure to cope with the expansion of air travel in the region, this year will increase by 7.2%. “There is great potential to develop if we work near the Governments to secure our future,” said IATA Director General, Tony Tyler, in an exhibition in the framework of the International Fair Air and Space Fair (FIDAE), held in Santiago, Chile. Tyler said that aviation in the region has a future “bright”, but success will depend “to be able to have the right conditions” for the industry. “Many of they require that both industry and governments work together towards a common vision and purpose, “he said. On the safety of passengers, last year was “the best ever” worldwide, while Latin America and the Caribbean Region was below average. “Traffic Latin America accounts for 6% of world traffic, but accounted for 27% of the total loss of aircraft hulls,” said the head of IATA. “If this does not improve, That means that with a like accident rate in six years the airlines here will experience a major accident every eight weeks, “said Tyler. Another problem facing the aviation industry in the region is the lack of airport infrastructure and management air traffic. “Infrastructure is clearly deficient in many countries but do not perceive a level of urgency among governments to solve the problem through integrated solutions,” said Tyler. The CEO of IATA said that the recent privatization of airports in Brazil seek making investments in infrastructure indispensable to the 2014 World Cup and Olympic Games 2016. Despite this, he was concerned about the high prices paid by new investors to the concessions. “The investments must be recovered through increased efficiency allow traffic growth, not through higher charges to airlines, “he said. also urged to cut rates for passengers and tourism in the region and criticized the allocation of tax collection. “The region collects to least four billion for airlines and their customers. There is little transparency in the allocation of these funds, but our best estimate is that less than one third falls on the industry, “said Tyler. The executive predicted that passenger traffic in Latin America will increase by 7.2% this year and that the benefits of the airlines in the region will reach one hundred million dollars. IATA brings together 240 airlines from 130 countries, representing 94% of international air traffic. http://tropicaldaily.com/uncategorized/lack-of-airports-hinders-tourism-growth-for-latin-america/ 10 | P a g e Latin America Ecotourism by Ron Mader Latin America is the cradle of ecotourism. What is it? There are many definitions of ecotourism, sustainable tourism and responsible travel. There is little consensus. That said, in our view ecotourism is overreaching at its finest and calls upon inter-sectoral alliances, comprehension and respect among stakeholders. While the details vary, ecotourism is special form of tourism that meets three criteria: 1) it actively facilitates environmental conservation 2) it includes meaningful community participation 3) it is profitable and can sustain itself. The tourism industry can be a leader, though recent history throughout the region is a series of battles between traditional tourism and those who promote alternatives. In many Latin American countries officials intrigued by the promise of ecotourism have attempted to regulate this niche market. In each case, the first challenge has been uniting energies of the tourism and environmental departments. Unfortunately, there have been more failures than successes as leaders have difficulty working together, preferring to be 'in charge' of projects that require collaboration and communication. CENTRAL AMERICA Central America is known as a prime destination for those seeking nature travel. This is due in large part to the reputation gained by Costa Rica over the past 20 years. Yet there are few efforts at developing the region for passionate eco travelers. The status is unclear of the Mesoamerican Ecotourism Alliance and the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor. These efforts were initially well-funded, yet neither organization has developed an effective communications infrastructure -- meaning that it remains a challenge to find out what these organizations are doing, who they recommended as local operators or guides. Cynicism arises from the fact that in the 1990s several Central American countries set up their own national ecotourism associations. Unfortunately, many of these have been created in government conferences, often at the urging of international development agencies. Few of which show a long-term commitment to ecotourism development. 11 | P a g e USAID, for example, funded and promoted several ecotourism associations throughout Central America, most of which existed solely on paper and disappeared within a year of their creation. Like "paper parks," "paper ecotourism organizations" give the illusion of action and coordination, but lack substance and continuity. Some operators prefer to work within existing organizations. In terms of national ecotourism organizations, it is interesting to note that Costa Rica, the country with the best reputation for ecotourism practices and destinations does not have a formal ecotourism group. Says Amos Bien, the owner of Rara Avis Lodge: "We've always been too busy to start a national ecotourism association, preferring to work within the sub-commissions of the Environmental Secretariat or the Costa Rican Tourism Institute instead." What is the role to be played by the national governments? In 1999 the Costa Rican Tourism Institute launched a certification program for hotel sustainability. The program's reputation is mixed. Some tout its usefulness and others consider it an example of greenwashing, the practice of giving a positive public image to an environmentally unsound practice. Honduras, for example, offers a great deal of potential in the field of ecotourism. The past few years have seen a number of new developments, but few have taken off. Obstacles, however, include a lack of coordination in-country and throughout the region. It remains a challenge to get current information from the government tourism institute, let alone details about eco-friendly tourism services. SOUTH AMERICA South America's best source of responsible tourism information is the South American Explorers, with clubhouses in Quito, Lima, Cusco and Buenos Aires. Travelers have access to well-stocked libraries and trip reports compiled by fellow members. In Ecuador a national ecotouurism association (ASEC), works on policy issues. However its communication, or lack thereof, frustrates members and travelers. In Brazil operators complain that the national government confuses authentic smallscale 'green' tourism with corporate concerns. Certification efforts have only confused matters. "There's no participation by anyone who can even remotely claim to represent tourists," says Bill Hinchberger, editor & publisher of BrazilMax. "Many of the participants at the meeting that created the Brazilian Sustainable Tourism Council (Conselho Brasiliero de Turismo Sustentável) spent much of their time dissing tourists. Now, many tourists deserve to be dissed, but not by certification groups that need to attract their support." "Even responsible tourists are unlikely to pay attention to certification. And if they don't, there's no point to this exercise," added Hinchberger."This is partly a marketing problem, but marketing seems to be at most an afterthought in all the certification schemes I've seen. 12 | P a g e MEXICO Mexico should be the case example of things done right. It is one of the few Latin American examples in which the Tourism and Environmental Secretariats signed an agreement to collaborate on ecotourism development. This took place in 1995. However, while the offices are officially working together, coordination remains problematic. Also, lack of continuity is a problem at federal- and state-level tourism levels. That said, Mexico has spurred on a number of initiatives, some regional, some national in scope. A group of private entrepreneurs set up their own group, an association for adventure travel and ecotourism (Amtave). Created in 1994, Amtave was the outgrowth of a coincidental meeting of nine associates who met at the annual Tianguis Turistico in 1993. Unable to afford marketing their companies, they formed a group to share the promotion expenses. Amtave raises its funds via membership fees and profits generated at events that the organization co-sponsors and promotes. This is not to say that everyone who offers nature or ecotourism in Mexico are -- or want to be -- members of AMTAVE. Many operators simply work out from environmental ethic and the knowledge that travelers are receptive to eco-friendly hotels and services. "People talk about ecotourism, but the fact is that the tourism industry is always looking for a quick buck," said one hotelier. "Hotels throughout the Copper Canyon still lack waste treatment facilities. Some of the garbage is thrown into the canyon or disposed of near community wells." MEDIA AND MARKETING Travelers interested in nature want to know how to get to where the wild things are and how to do so in a responsible manner. Unfortunately, governments rarely provide quality, up-to-date information for the general public. One missing ingredient is visual information, including maps. The tourism institutes of both Costa Rica and Honduras publish country maps showing how to visit protected areas. Mexico once published such a map (1995), but it quickly went out of print. One of the best tools for travelers to find information about ecotourism destinations is not from government offices or environmental groups, but from regional guidebooks. Guidebooks offer a holistic vision of a country or a region and are publicly accessible. The author freely crosses political and/or vocational borders to provide a manual of use to travelers from a variety of backgrounds. 13 | P a g e A key text that deserves special kudos is The New Key to Costa Rica (Ulysses Press), one of the first guidebooks that explained the concept of ecotourism and sustainable development and promoted the hotels and lodges that were working toward environmental protection. Such books contrast with more traditional guidebooks that either belittle the "friendly people" or focus only on more popular coastal resorts. Such books are instrumental not only in directing travelers where to go, but how to travel in a responsible manner. WHAT'S NEXT? One of the frequent discussion threads during the Media, Environment and Tourism Conference is the value of local reporters versus parachute journalists. Why don't we write more about the places where we live? No doubt the next stage of ecotourism reporting will be conducted more by travelers and locals. A good example is the afterwilma website, created to track news about development after Hurricane Wilma. While it's not focused on ecotourism, it pays attention to 'sustainable tourism' and has provided an opportunity for hundreds of people to collaborate in commons-based peer production. 14 | P a g e

![Ecotourism_revision[1]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005398532_1-116d224f2d342440647524cbb34c0a0a-300x300.png)