Balancing selection

advertisement

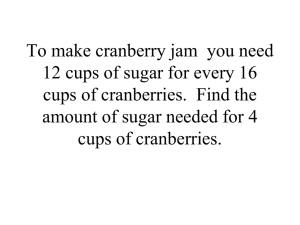

Miller 1 Katie Miller Biology 303 Honors Dr. Bert Ely November 1, 2012 The Balancing Selection Hypothesis and Explaining the Survival of Homosexual Genes For many years both science and society alike have grappled with the existence of homosexuality. What started as something many in Western society shunned and the medical community classified as a mental disorder, acceptance of homosexuality in humans is now something very commonplace and, in most places no longer considered a crime or an illness. However, we as a society are still trying to figure out the origins of this variance in sexual orientation. Most agree that homosexuality is something an individual is born with and is not a choice. But, the influence of genes on sexual orientation is something that has not yet been explained. A curious question arises as explained by Blanchard (2012): “How can genetic variants that predispose to homosexuality remain at a (seemingly) constant rate in the population, when the men who carry them are so much less likely to produce offspring?” An almost perfectly precise answer to this question is the Balancing Selection Hypothesis. As defined in Blanchard’s 2012 paper by Schwartz et al. (2010), the Balancing Selection Hypothesis is explained by saying “the decreased fertility of men with the heritable form of homosexuality is offset by an increased fertility of biological relatives who carry the same genetic variants.” The Balancing Selection Hypothesis is a possible answer as to why these genes predisposing individuals to homosexuality are not decreasing from the population. Blanchard’s 2012 research used six previous studies’ data to correlate evidence for the Balancing Selection Hypothesis and built on the research of Camperio-Ciani et al. (2004) and Iemmola and Camperio-Ciani (2009) that first outlined a correlation between homosexuality and the birth rate in the relatives of homosexual men. Blanchard formulated his hypothesis with the help of two papers, one being CamperioCiani et al. (2004) which documented an increase in fecundity (fertility) from the female Miller 2 maternal members of the homosexual subjects’ families. The same increase, however, was not found in the heterosexual subjects’ relatives. In Camperio-Ciani et al. (2004), 98 homosexual and 100 heterosexual men from northern Italy were studied. Each filled out a survey providing their family size, sexual orientation of male relatives and birth order and gender of siblings. The data showed that the homosexual men’s maternal side of the family had increased fertility and also these subjects had more older siblings, in particular more older brothers, than their heterosexual counterparts. The paternal side of the family did not have an increase from either group. Later the researchers discussed how this increase in maternal fecundity of homosexual men and no change in paternal fecundity of heterosexual men showed a correlation that would lead to a hypothesis suggesting that these genes are linked to the X chromosome (Camperio-Ciani et al. 2004). The second paper Blanchard (2012) used as the basis of his research was Iemmola & Camperio-Ciani (2009). In this paper, 250 probands (test subjects) were sampled with 152 being homosexual. These men were mostly picked from tourist industry jobs, so they likely came from all over Italy despite the sampling haven taken place in Northern Italy, similar to Camperio-Ciani et al. (2004). Again the men filled about a survey about their family size and demographics. The researchers also asked about how many children each group of probands had. The homosexuals had about one fifth of the children the heterosexuals had, showing the natural decline in passing on the genes. Once again the data showed that homosexuals had a higher maternal fecundity rate than the heterosexuals and had a greater difference than with the previous study, which yet again showed a possible X chromosome link to these genes. However, this study also showed a higher paternal fecundity rate. The researchers admitted that there was a bit of sampling bias in how they recruited probands (since they went to bars, resorts, clubs, gyms, etc. to recruit homosexuals and to the same types of places to recruit heterosexuals, it probably resulted in an oversampling of non-married heterosexuals) and they stress the importance of repeating the experiment with a larger sample to eliminate biases and to try to repeat the results (Iemmola & Camperio-Ciani 2009). The main paper that tested the Balancing Selection Hypothesis is Blanchard 2012. Blanchard built onto the ideas presented by both Camperio-Ciani et al. (2004) and Iemmola & Camperio-Ciani (2009) and took it one step further. Instead of testing the probands’ entire family size, Blanchard (2012) instead focused on the number of siblings each subject had. While just Miller 3 testing sibling numbers, the Balancing Selection Hypothesis still applies but this time focused on the mothers of the probands (Blanchard 2012). Also, Blanchard (2012) only used first-born homosexual and heterosexual probands to eliminate any bias from the Fraternal Birth Order effect (FBO effect). Blanchard (2012) cites the Zietsch et al. 2008 definition of FBO as an effect “… where males with a greater number of older brothers and sisters are more likely to be homosexual …” The direct mechanics of why the FBO has an influence with homosexuality is not elaborated in these papers, but both previous papers, Camperio-Ciani et al. 2004 and Iemmola & Camperio-Ciani 2009, show a trend where homosexuals who have more siblings tend to have many more older brothers and sisters than younger (Camperio-Ciani et al. 2004 and Iemmola & Camperio-Ciani 2009). So to eliminate any bias from the FBO effect, Blanchard (2012) only used first-borns because the Balancing Selection Hypothesis should still have applied (Blanchard 2012). In his study, Blanchard (2012) used data from six previous papers(he participated in all six). These papers all have slight differences among how their data was presented but otherwise have almost the same main idea: 1) Blanchard and Bogaert 1996a (first-borns 18 and older sampled to prevent incomplete sibships) 2) Blanchard and Bogaert 1996b (used a full heterosexual group instead of subdividing to match each homosexual group) 3) Blanchard and Lippa 2007 (combined bisexual and homosexual probands into one group instead of keeping them separate) 4) Blanchard and Zucker 1994 (used this studies data; in the original study the family size mean was calculated including the probands in the family size, but it was corrected for use in Blanchard 2012) 5) Blanchard et al. 2006 (eliminated one group sampling because it did not include data on younger siblings. This study only uses 2,764 of the 3,146 probands of the original study) 6) Blanchard et al. 1998 (this study did not compare number of siblings of the homosexuals and heterosexuals against each other; this error was corrected for Blanchard 2012) Miller 4 Blanchard’s results were quite surprising and unexpected. Having only tested first-born homosexual and heterosexual probands, the results showed either that the heterosexuals had more siblings than the homosexuals or that the data was not statistically significant. Also, the mothers of both groups of probands had statistically more children than average (about 2.1 births for industrialized countries) which showed that the probands sampled have some sort of increase in maternal fecundity rate yet the heterosexuals still had more siblings than the homosexuals. These results were in direct contrast to the Balancing Selection Hypothesis (Blanchard 2012). As Blanchard (2012) quoted himself in the discussion section, “What can explain the discrepancy?” Blanchard threw around a number of ideas including, but not limited to, the FBO effect, sampling bias, too small of a sample and not taking into account birth weight of the probands to test for discrepancies in the womb. He also said this study would need to be repeated so as to replicate the results. He believed that replication would be easy considering that there are already lots of data archived on this subject that could be examined and compiled into another study. Blanchard supported more research on the subject because until this paper was published, the two previous papers, Camperio-Ciani et al. 2004 and Iemmola & Camperio-Ciani et a. 2009, confirmed the Balancing Selection Hypothesis (Blanchard 2012). Whether there was an error in Blanchard’s 2012 paper or not, the Balancing Selection Hypothesis is one of the most comprehensive and plausible hypotheses proposed in recent years to explain how a genetic aspect related to homosexuality in humans could survive in the population. Researchers should still consider it a valid direction of thinking until more definitive answers come to light, especially with data both confirming and denying this hypothesis. Literature Cited Miller 5 1. Blanchard, R. 2012. Fertility in the Mothers of Firstborn Homosexual and Heterosexual Men. Archives of Sexual Behavior 41:551–556. 2. Schwartz, G., Kim, R. M., Kolundzija, A. B., Rieger, G., & Sanders, A. R. (2010). Biodemographic and physical correlates of sexual orientation in men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 93–109. 3. Camperio-Ciani, A., Corna, F., & Capiluppi, C. (2004). Evidence for maternally inherited factors favouring male homosexuality and promoting female fecundity. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B, 271, 2217–2221. 4. Iemmola, F., & Camperio-Ciani, A. (2009). New evidence of genetic factors influencing sexual orientation in men: Female fecundity increase in the maternal line. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38, 393–399. 5. Zietsch, B. P., Morley, K. I., Shekar, S. N., Verweij, K. J. H., Keller, M. C., Macgregor, S., et al. (2008). Genetic factors predisposing to homosexuality may increase mating success in heterosexuals. Evolution and Human Behavior, 29, 424–433.