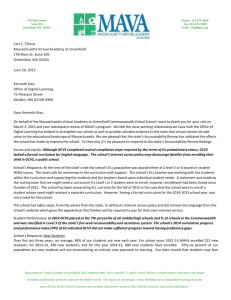

March 2015 Accountability Review Report: Massachusetts Virtual

advertisement