WB_4 - SEAS

advertisement

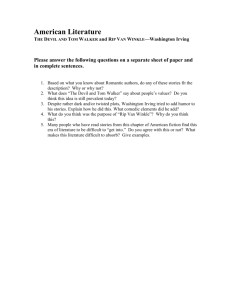

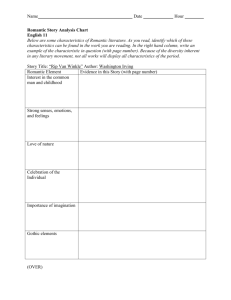

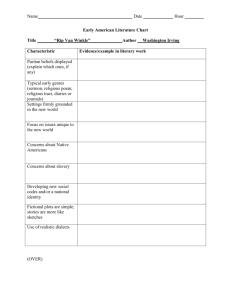

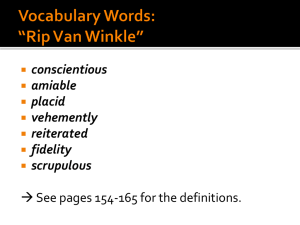

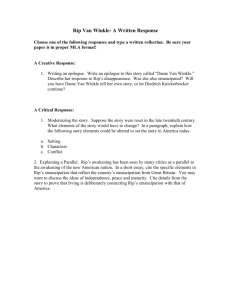

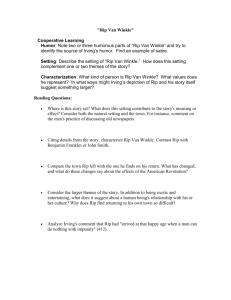

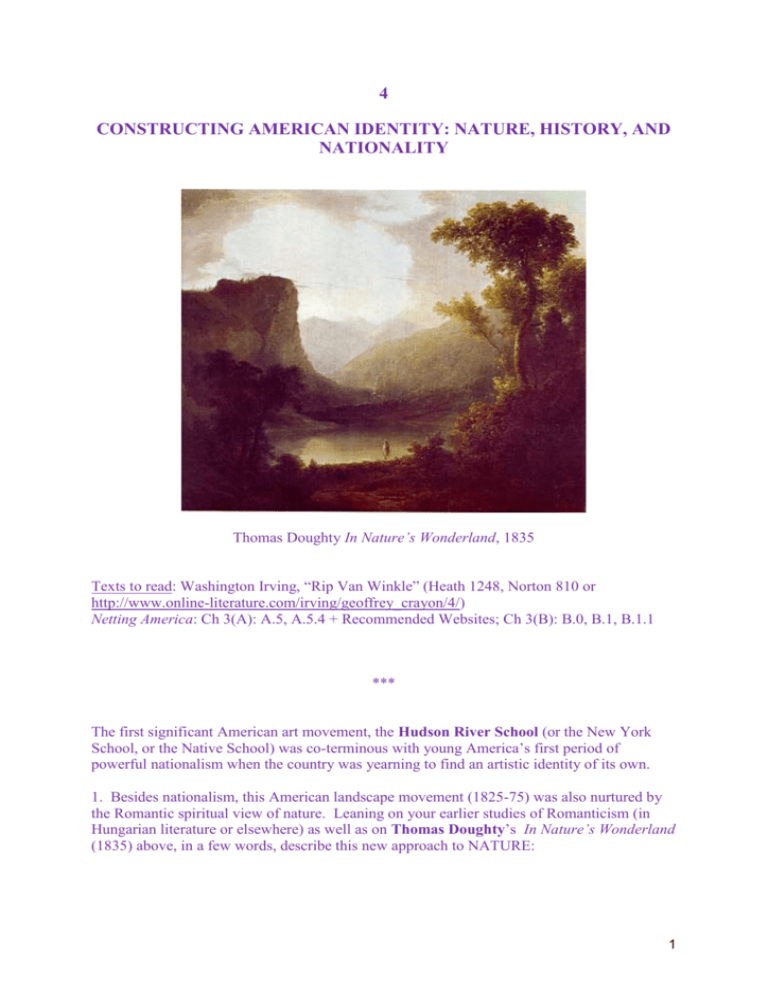

4 CONSTRUCTING AMERICAN IDENTITY: NATURE, HISTORY, AND NATIONALITY Thomas Doughty In Nature’s Wonderland, 1835 Texts to read: Washington Irving, “Rip Van Winkle” (Heath 1248, Norton 810 or http://www.online-literature.com/irving/geoffrey_crayon/4/) Netting America: Ch 3(A): A.5, A.5.4 + Recommended Websites; Ch 3(B): B.0, B.1, B.1.1 *** The first significant American art movement, the Hudson River School (or the New York School, or the Native School) was co-terminous with young America’s first period of powerful nationalism when the country was yearning to find an artistic identity of its own. 1. Besides nationalism, this American landscape movement (1825-75) was also nurtured by the Romantic spiritual view of nature. Leaning on your earlier studies of Romanticism (in Hungarian literature or elsewhere) as well as on Thomas Doughty’s In Nature’s Wonderland (1835) above, in a few words, describe this new approach to NATURE: 1 2. Stately portraits and canvases depicting historical scenes adorned only certain private homes and grand public institutions; paintings representing wild American nature, on the other hand, “offered a universal, and more democratic artistic expression to be exhibited in any parlor and admired by any viewer” (Louise Minks). So the landscape as a theme and genre gained special significance in the young American republic and it came to be regarded as congenial to American democracy. On what basis do you think this is a tenable argument? Try to reason as early nineteenth-century Americans could have for the interconnectedness of the American landscape with American democracy. 3. Read William Cullen Bryant’s lines from “To Cole, the Painter, Departing Europe” and paraphrase this excerpt from his poem, also describing their implications with regard to the specificities of American landscape painting. Do this in a way that makes it come alive in your own imagination. Fair scenes shall greet thee where thou goest – fair But different – everywhere the trace of men, . . . Gaze on them, till the tears shall dim thy sight, But keep that earlier, wilder image bright. 2 4. Study Thomas Cole’s Sunny Morning on the Hudson River (c. 1827) and describe what you can see in the picture. Allow your eyes to see from an artist’s perspective, so that you are not just listing details. Pay attention to its tripartite structure (foreground, middle ground and background) that Cole learned from his predecessors, the French artist, Claude Lorraine, and the Italian Salvator Rosa. Thomas Cole, Sunny Morning on the Hudson River, c. 1827 3 5. After reading Washington Irving’s “Rip Van Winkle,” what associations can be made between the picture painted by Sanford Robinson Gifford below and the picture drawn by Irving of the Kaatskill Mountains in his story? Namely, how does Irving’s introduction depicting the Kaatskill Mountains relate to this picture? Sanford Robinson Gifford, Kauterskill Clove 1862 4 6. As suggested by Asher Durand’s famous picture, Kindred Spirits (on the cover of your Norton Anthology vol. 1!), poets and painters shared many interests and perspectives in spite of the differences in their artistic medium. (Their common interests and enthusiasm fomented friendships, such as among Durand, Cole and Bryant.) An especially good example is Washington Irving and John Quidor, who were both fascinated with picturesque representations of everyday life. This type of interest by Quidor and others (George Caleb Bingham, William Sidney Mount) was realized in genre painting, which was the other type of painting flourishing in the mid-19th-century. Use your dictionary, but first define these words from your own knowledge. a) Now, look up picturesque, and then write down its definition(s). How does it compare to what you thought it meant? b) Compare picturesque with sublime. Were your ideas correct before you used the dictionary or did you find the dictionary a good tool to understand these better? 5 7. Study John Quidor’s The Return of Rip Van Winkle (1829). Using Washington Irving’s words and phrases from his own representation of Rip’s return, describe the scene in Quidor’s picture. Besides the characters, take note of the picturesque local details that both the story and the picture have in common. John Quidor, The Return of Rip Van Winkle 8. Have a close look at Irving’s story again and using the author’s words, give a short description of the main characters. Instead of complete sentences, you may opt to pick only a few characteristic words or phrases from respective passages of the text: The Author, D.K. (from The Author’s Account of Himself and Note): 6 Rip Van Winkle: a) before his trip to the Kaatskills b) after his trip Dame Winkle: The odd-looing personages playing at nine-pins: The orator in Rip’s village: Rip Van Winkle Jr.: Judith Gardenier: Peter Vanderdonk: 9. This apparently sketchy and humorous story takes a sinister turn from the comic to the near-tragic at one crucial point. a) Where does this change occur in the text? Write down the first sentence of this passage. 7 b) Where is the climax of this eery scene? Write down the sentence(s) used to this effect. 10. Why do you think Washington Irving structures his story into 3 parts? See 1) The Author’s Account of Himself, 2) Rip Van Winkle, 3) Note *** Try to think of the answer by recalling what happens in those parts and how they relate to one another. 11. The scene captured by Quidor, renders the beginning of a historical allegory, which Irving works out at the end of his narrative. So both artist and writer stress the importance of change in Rip’s life as an allegorical potential with which to capture the essence of the culture of the USA. Briefly explain this allegory of history by translating Rip’s life into the history of his country. *** Before engaging with this problem, search for a tenable definition of allegory either in a dictionary or on the internet. If you’ve encountered several descriptions, make up your own, based on the recurring (or even same) words and phrases in your findings. 8