SSR Bornstein

advertisement

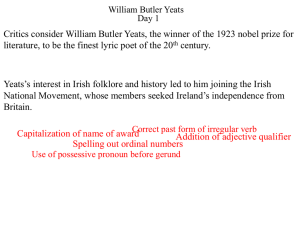

Bettina Lemm SSR- Bornstein Bornstein, George. "Of What Is Past, or Passing, or to Come: Recent Years of Scholarship." Modernism/Modernity 16.4 (2009): 609-14. Project MUSE. Web. Hook: The title of Bornstein’s article is a verse that alludes to Yeats’ poem “Sailing to Byzantium.” The author then gives us a works cited list of the five books that he will review in his article. This means that from the start, Bornstein offers a quick outline of what his argument will be. He will look at individual books and examine how each book is a different method for the scholarly study of Yeats. Thesis: He spreads out his main argument across the main paragraph- “Sixty years ago those pioneers of the first generation of Yeats scholars Richard Ellmann and Thomas Parkison had to legitimate in their graduate programs […]the acceptance of a doctoral dissertation on so a recent writer as Yeats…The books discussed here exemplify the impressive textual, critical, and historical scholarship of the generation that came after Ellmann and Parkinson, and therein lies both their glory and their limit. On the one hand, that they bring such historical, biographical, critical, and textual approaches to disparate culminations make them worth the attention of any student modernist poetry…On the other hand, methodologically their work displays an indifference to changes in literary study for the past three decades that leaves plenty of territory for future scholars to investigate (610).” Bornstein argues that the study of Yeats is relatively new and still evolving. The generation of scholars that really solidified the study of Yeats were Vendler, Grene, Schuchard, Gould, and Finneran, who’s books we will learn about in the article. Borstein wants to convey that the study of a text or an author can vary depending on the approach, or context. The scholars the article investigates have different approaches from historical to critical and although their study of Yates is thorough, there is still room for new scholars to develop their own methods of study. Line of argument: If Bornstein was to make an outline of his paper, his topic sentences would be headed by the titles of the different books. He begins with Richard Finneran’s The Tower: Manuscript Materials. Like the title suggests, Finneran collected all of the original manuscript drafts of all of Yeats’ poems. Bornstein finds it important to note that Finneran did all of his research in the “pre-internet age of card catalogues, handwritten lists, and often expensive travel to collections (610)”. From this sort of compilation of work, Bornstein highlights three opportunities for scholars today: understanding the evolving themes in Yeats’ work, understanding the orderings of the poems, and paying attention to “the material text (611),” since Yeats paid special attention to the cover design and such. Finneran’s enabling the study of the material text leads Bornstein to the next scholar, critical reader, Helen Vendler. The material text is only a display for what really matters- the content. Vendler offers a thoughtful book on Yeats in what Bornstein considers is “the best reading we have yet of Yeats in formalist terms (611).” Vendler does an analysis of techniques in Yeats’ early poems and then organizes them by genre. Vendler failsin paying closer attention to the form of Yeats’ poetry and his “design of individual volumes” (612) and how intentional he was about page layout and book covers. Third, Bornstein looks at Nicholas Crane and claims that Crane is more “relaxed” than Vendler. In his book, Crane talks about “poetic codes”- special words that tell us “not so much of the meaning of Yeats’s poems, but of how they mean what they mean” (613). Crane points out that Yeats would manipulate historical context and dates in order to manipulate meaning. Apparently Yeats manipulated the actual age of one of his characters, Maud Gonne, so that it would tie in with his story. More importantly, Bornstein calls attention to the fact that Crane used Finneran’s volume as a reference for the dates of composition of poems such as “Sailing to Byzantium.” This helps the reader grasp more thoroughly how these books serve as references and make for good, scholarly research because they complement and contribute to one another. Next, the article touches on Ronald Schuchard’s The Last Minstrels: Yeats and the Revival of the Bardic Arts and how the book examines Yeats’s poetry from a historical perspective through the tradition of chanting poems orally. Finally, Bornstein brings up Influence and Confluence, Yeats Annual No. 17 by Warwick Gould. This last text is the most specialized of the five according to Bornstein, and specialization provides a “solid ground for broader work” because the book includes thoughtful reviews by others (614). However, this last book is so specific on Yeats’s work that it overlooks the literary movement that was occurring around Yeats. In his concluding paragraph, Bornstein tells us why his quick overview of these five books is important. He poses the question of who the intended audience for these books is. The books are all pricey, limiting them only to an exclusive group of experts. However, Bornstein condemns that approach and suggests that this sort of research should be made available and accessible to other scholars and not just experts. Techniques that motivate/inspire/encourage me and some that bother me: -Bornstein uses descriptive action verbs. “Her opening chapter on three well-known lyrics exemplifies her pervasive virtues… (612).” ; Vendler swiftly zeroes in on telling details… (612).” -His article is not just a summary of these five books, or a “list of grievances.” He does not just make a critique of the books; he also offers suggestions for improvement. “His convincing argument might have had wider effect in condensed form rather than at 447 pages, especially if he had included examples of how knowledge of the chanting context can illuminate individual poems (613).” -I do not like how he devotes so many paragraphs to talking about Finneran and Vendler, but by the third writer, it is almost like he notices he has been talking too much and he shortens the length of what he has to say for the last three, particularly the last two books. This is even evident in the way that I analyzed his argument and how I had more to say about the first two authors and their books.