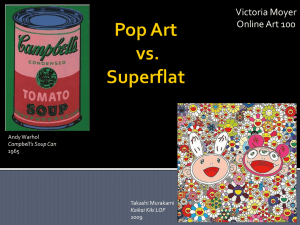

A Reflection of Postmodern Japanese Society

advertisement