NaomiMartinez-Whose Skeleton is it anyways

advertisement

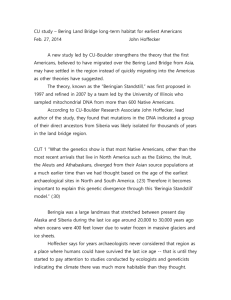

Whose Bones are they anyways? Whose Skeleton is it anyways? For SBS 200 Professor Morley By: Naomi Martinez May 11, 2015 California State University, Monterey Bay 1 Whose Bones are they anyways? Figure 1. Map showing Kennewick, Washington. Figure 2. Topographic map showing the locality where the Kennewick skeleton was found. 2 Whose Bones are they anyways? 3 Introduction During class discussions of the Kennewick Man, we have concentrated on a controversial issue regarding whether or not anthropologists and scientists should control Native American skeletal remains for study or be repatriated to the Native American tribes. In this essay I will argue that these remains must be rightfully reburied because under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA, 1990), tribes should be returned what is rightfully theirs. On one hand, keeping the remains for study is a great idea because it gives us a look at prehistory generations and generations to come (Chatters, 312). On the other hand, and I will demonstrate why, the remains should be repatriated to its rightful owners. I will begin with an examination of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA, 1990). Though I concede that studying this remain is essentially beneficial for science and mankind, I still maintain that the remains belong and deserve to be with their tribe, to be left in peace and reburied according to traditional practices. The issue is important because it not only involves a controversy between two very different, but important groups. There is really no right or wrong answer, which is, who really has the right to keep remains and what should be done to figure this out. Whose Bones are they anyways? 4 Brief Background of the Case It was July 28, 1996 when two college students were walking along the Columbia River to sneak into the annual boat races, in Kennewick, Washington (Coleman, 66). One of the students tripped over what turned out to be a human skull and quickly contacting enforcement, the skeleton was extracted from the river (Coleman, 66). James Chatters, an anthropologist who lived near the area, was called to study the skeletal remain and as he was carbon dating the remain, Kennewick city workers “contacted officials who managed the river and natural resources, including members of the Umatilla Tribe, to decide what to do with the skeleton” (Coleman, 66). Kennewick Man, became a global sensation when Chatters learned the body was over 9,000 years old, making it the oldest skeletal remain found in North America (Coleman, 66). He stated that Kennewick Man does have similar traits with other Paleoamerican males, although he’s taller and “has a more projecting face” (Chatters, 312). What was not determined was the way he died but “acute and chronic bone infections point to septicemia and a possible, final shoulder-dislocating injury is a strong candidate” (Chatters, 312). Coleman explains that James Chatters saw this as “‘an opportunity to learn from ancient ancestor and to convey what [could be said about] future generations’” (Coleman, 66). Local tribes, backed by the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (1990), “requested the return of Kennewick Man” (Coleman, 66). Chatters, with the help of fellow anthropologists, immediately called together eight scientists who sued for the right to study the remains (Coleman, 66). Attorneys, reporters, politicians, scientists, and Native American activists “struggled to make their voices heard in the circuits of discourse” (Coleman, 66). For almost a decade a controversy between the scientists and tribes occurred over who should keep the remains. Whose Bones are they anyways? 5 The NAGPRA Pensley argued that museums failed to represent Native American “culture accurately and appropriately,” keeping and showing off Native American “human remains, sacred and culturally sensitive materials;” (Pensley, 37) and sometimes having to use violence to obtain some of the objects museums hold in their collections, is what NAGPRA exists to stand for. NAGPRA is a legislation that protects Native American “burial sites and regulates, through administrative permitting, the removal of human remains, burial artifacts, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony located on federal or tribal lands” (Pensley, 38-39). NAGPRA also oversees how quickly something is repatriated to a tribe and it “encompass enforcement mechanisms,” (Pensley, 39). NAGPRA shouldn’t be seen for what it seems to accomplish, but for the language and ideas it stands for, and that’s to remember and respect the dead (Pensley, 39). Just as anything, NAGPRA isn’t perfect and it has faced situations where not everyone is happy or Native American’s voices weren’t heard. Pensley states that someone can’t claim a “piece of personal or real property,” because the item is owned by many (Pensley, 54). Whose Bones are they anyways? 6 The Scientists Weiss states that under NAGPRA rules, the government has 30-days to tell in local newspapers its intentions of repatriating a skeleton (Weiss, 14). “During this 30-day waiting period, and before the Army Corps of Engineers could hand over the bones to the coalition of Columbia River tribes headed by the Umatillas, eight anthropologists filed suit against the repatriation of the skeleton on the grounds that Kennewick Man might not be a Native American and, thus, not subject to NAGPRA” (Weiss, 14). Weiss states that “if Kennewick Man had been reburied immediately, it would have been a major loss to research on the origins of the prehistoric peoples of America and” could have been used as evidence that the Caucasoids were early settlers (Weiss, 15). My Argument It’s just crazy to think that Kennewick Man has been a controversy for over a decade now. Although Chatters states that Kennewick Man is beneficial to science for knowing what occurred during those times I feel like there’s no need for it because there is so much we already know about history that I think that it’s enough. The anthropologists are being selfish and thinking about their career and not considering the feelings of the people who the body belongs to. Kennewick Man should be repatriated to its rightful owners because that is what should happen when under NAGPRA (1990). I understand that reburying remains leads us to losing precious evidence, but Native Americans have the right to rebury their ancestors. And that’s the thing, since Native Americans have been walked all over almost all their lives, people think it’s still okay to do that, when in reality, it’s not. A person doesn’t really know how it feels to go through that situation. Whose Bones are they anyways? 7 My Conclusion Kennewick Man is the remains found near the Columbia River. This skeleton has become a global controversy because it involves two very different, but important groups, the anthropologists and the Native Americans. Under NAGPRA, what should have already been done was the repatriation of the body, but since anthropologists kept it for scientific purposes, the body wasn’t repatriated to the tribe who rightfully owns it. The body is 9,000+ years old, there’s so much that you can get out of a body. We have enough knowledge of history that another body isn’t necessary. Kennewick Man should and needs to be repatriated to its tribe because there’s just no need for this controversy, because what should be done should’ve been done a long time ago and that is that the rules of NAGPRA should be obeyed. Whose Bones are they anyways? References: Chatters, J. (2000). The recovery and first analysis of an early Holocene human skeleton from Kennewick, Washington. American Antiquity, 65(2), 291-316. Coleman, C. (2013). The extermination of Kennewick man’s authenticity through discourse. Wicazo Sa Review, 28(1), 65-76. Pensley, D. (2005). The Native American graves protection and repatriation act (1990): Where the native voice is missing. Wicazo Sa Review, 20(2), 37-64. Walker, D. & Jones, P. (2000). Other perspective on the Kennewick man controversy. American Anthropologist, 102(4). 907-910. Weiss, E. (2001). Kennewick man’s funeral: the burying of scientific evidence. Politics and the Life Sciences, Vol. 20, No. 1, pp. 13-18 8