Palaeontologist careers

advertisement

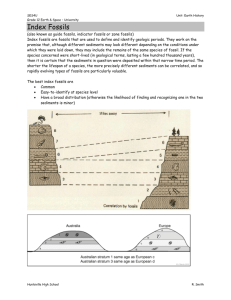

Palaeontologist Introduction Palaeontologists study fossils to develop knowledge of ancient life forms and their environments. Palaeontology can also reveal how the environment and climate have changed over time. Palaeontologists are involved in research, education, managing museum collections, and the exploration of oil, coal and gas. Work Activities Palaeontologists study fossils to develop knowledge of ancient life forms, including their anatomy, physiology, evolution, and the ecosystems that they would have been part of. Palaeontologists can establish which plants and animals lived in particular areas. The types of fossils found can reveal if the area used to be a desert, forest, river bed, ocean floor, etc. This gives us information about climate and environmental change. They can also use fossils to establish the type and age of the rocks that contain them. This information helps in the exploration of oil, coal and gas because certain rock layers are more likely than others to contain deposits of these resources. Fossils are usually preserved in layers of sedimentary rocks. Palaeontologists can identify them based on their shape, size and the material they are made from. While fieldwork to find fossils is very important, palaeontologists spend most of their time in laboratory work. This involves preparing specimens, doing experiments and analysing the results, working with other scientists and writing up results in scientific papers and reports. Palaeontologists usually have very specialist knowledge of one particular area of the science. They often also have expertise in a related area, such as oceanography, anatomy or evolution. They might be experts on: Vertebrate palaeontology, for example, fish, reptiles, dinosaurs, birds and mammals. Invertebrate palaeontology, such as sponges, corals and molluscs. Micropalaeontology - small, single-celled or multi-celled organisms. Palaeobotany - larger, multi-celled fossil plants. Invertebrate palaeontology involves the broadest range of fossils, including those that are most likely to be found in fieldwork, such as ammonites. Most of the academic posts in palaeontology are to do with invertebrates. However, most professional palaeontologists are involved in micropalaeontology. This is partly because of the area's importance in the search for fossil fuels like oil, coal and gas. Also, microfossils are widely found across the world. They can often be collected without the palaeontologist being there, for example, when they are gathered up in mud taken from oil, gas and water wells. When oil is drilled, pieces of rock come to the surface. These can contain microfossils. With further drilling, the microfossils that are uncovered become older and older. Palaeontologists can date these microfossils, which helps them to work out the age of the rock that is being drilled and therefore to predict the presence of oil. A very small number of palaeontologists work in palaeobotany. This is a highly specialised area. It plays an important part in increasing our understanding of ancient ecosystems, including the animals that would have eaten the plants. Fossil plant data is widely used in climate change studies. In a museum, a palaeontologist working as a curator would probably divide their time between activities such as: Checking the physical condition of the fossils. Cleaning and repairing fossils ready for display. Updating computer records of the collection. Searching for new fossils, including negotiating to add them to the collection. Answering enquiries from other academics. Organising public events, exhibitions and talks. Working with volunteers. Applying for funding. Academic research. Academic palaeontologists, for example, in a university, will spend time on their own area of research. They also give lectures, mark essays and support PhD students. Personal Qualities and Skills To become a palaeontologist, you'll need: An interest in ancient life forms and ecosystems. An interest in environmental issues, such as climate change, can also be important. Laboratory skills, for example, using techniques like radiometric dating to establish how old fossils are. Patience to be involved in a research project over a long period of time. Communication skills to work with other scientists, write reports of your findings or give talks and lectures to the public in a museum. Computer skills for tasks such as research work or updating museum collection databases. Willingness to do fieldwork, including in remote areas. Pay and Opportunities Pay Salaries for palaeontologists vary. The pay rates given below are approximate. Palaeontologists earn in the range of £25,000 - £30,500 a year, rising to £40,000 - £45,000 with experience. Higher salaries are available depending on employer, role and responsibilities. Hours of work Palaeontologists usually work 35-39 hours a week, Monday to Friday. Demand This is a small profession, with fierce competition for jobs. Where could I work? Most employment is with universities, museums and consulting organisations. There are opportunities in the four broad categories of palaeontology: Micropalaeontology offers the greatest number of commercial job opportunities, for example, in the energy, oil and gas industries. Invertebrate palaeontology offers most academic job opportunities, mainly in universities (although there are still not many vacancies). Vertebrate palaeontology offers only limited academic job opportunities, mainly in museums. Palaeobotany is a small area of employment. Most is in academic departments allied to botanical training programmes, with a few commercial opportunities. Where are vacancies advertised? Vacancies are advertised on the Natural History Museum website; in science magazines such as New Scientist (which also posts jobs on its website); on specialist job boards (academic, scientific and for the energy, oil and gas industries); and in national newspapers. Entry Routes and Training Entry routes Usual entry is through a first degree in a relevant subject. Most entrants have degrees in geology or earth science. Entry can be possible with a degree in a biological science subject.. Although this is much less common generally, many palaeobotanists, for example, have a background in botany rather than geology. When looking at a geology/earth science degree course, you should check to make sure the course includes topics relevant to palaeontology. A small number of specialist degrees are available, for example, in palaeontology, palaeobiology, and geology with palaeobiology. For a specialist first degree course, A level Biology might be specified. Please check prospectuses carefully. You will then usually need a postgraduate qualification (either an MSc or PhD) in palaeontology. Most palaeontologists in the oil, coal and gas industries have an MSc. Museum-based research palaeontologists and university lecturers almost always have PhDs. In museums, palaeontological curators have at least a degree. Many will also have an MSc or PhD. Entrants to museum work have usually first gained skills and knowledge through voluntary work experience. Training You might have training on-the-job in particular lab techniques or specialist equipment. Palaeontologists also go to conferences, seminars and workshops to develop their knowledge. Progression In universities, palaeontologists can progress to become senior lecturers and professors. In industry, progression could be to a supervisory or management position. Qualifications Most entrants have a first degree in geology or earth science, followed by a postgraduate qualification in palaeontology. For entry to a degree in geology, the usual minimum requirement is: - 2/3 A levels, including at least one science subject, Maths or Geology. Some universities accept Geography as a science subject. - GCSEs at grade C and above in your A level subjects. - A further 2/3 GCSEs at grade C and above, often to include English and Maths. Alternatives to separate science GCSEs (Biology, Chemistry and Physics) are: - Science and Additional Science, or - Science and Additional Applied Science. Equivalent qualifications, such as Edexcel (BTEC) level 3 Nationals and Progression or Advanced Diplomas might be acceptable for entry. However, some universities will accept these only alongside the A levels they ask for. Please check prospectuses carefully. Adult Opportunities Age limits It is illegal for any organisation to set age limits for entry to employment, education or training, unless they can show there is a real need to have these limits. Skills/experience Some entrants have skills and abilities gained in laboratory work during relevant work placements, or in relevant scientific fieldwork. Courses If you don't have the qualifications needed to enter a relevant degree course, you might be able to start one after completing an Access course (for example, Access to Science). You don't usually need any qualifications to start an Access course, although you should check individual course details. A foundation year before the start of a science degree is available at some universities and higher education colleges for students who don't have the science A levels usually needed for entry to the course. Birkbeck College (University of London) offers degree and postgraduate courses in geology and earth sciences. It offers these on a flexible basis: part-time (evenings) or by distance learning. The Universities of Leeds, Brighton and Derby also offer part-time degrees in geology. The Open University offers a degree in Geosciences, by distance learning. Funding Funding for postgraduate study and research is available, through universities, from the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC). Statistics 6% of people in occupations such as palaeontologist work part-time. 14% have flexible hours. 8% of employees work on a temporary basis. Further Information Resources New Scientist. New Scientist. (www.newscientist.com) Contacts Geological Society, Burlington House, Piccadilly, London W1J 0BG. Telephone: 020 7434 9944 Website: http://www.geolsoc.org.uk Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD. Telephone: 020 7942 5045. Website: http://www.nhm.ac.uk Palaeontological Association, Website: http://www.palass.org