Maria Lucia Karam

advertisement

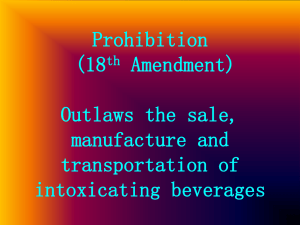

DECRIMINALIZATION VERSUS LEGALIZATION OF DRUG TRAFFICKING Maria Lucia Karam I speak on behalf of Law Enforcement Against Prohibition (LEAP), which is a nonprofit organization made up of current and former members of the law enforcement and criminal justice communities who have enforced drug laws and understood the failures and harm provoked by the existing drug policies. Drugs that are now illegal were prohibited worldwide at the beginning of the twentieth century. In the early 1970s, the “war on drugs” was declared by former North American president Richard Nixon, and soon spread throughout the world. Nevertheless, illegal drugs keep getting cheaper, more potent, more diversified and far easier for everyone to access than they were before they were prohibited and their producers, sellers and consumers were branded as “enemies” in this war. Prohibition, however, is not only a failed and ineffective policy. It is much worse than that. Besides increasing the risks and harm caused by drugs themselves, prohibition causes more serious risks and harm, the most evident and tragic of which is violence – a logic outcome of a policy based on war. Much more people die because of drug prohibition than because of drugs themselves. It is prohibition that creates and places in what before was a legal market the gangs, the cartels and mafias. The production and supply of illegal drugs have become the main opportunity for profits from illicit activities, and therefore the greatest incitement to the corruption of state officials, along with providing money for other illicit activities, among which is terrorism. Prohibition implies the lack of any control of the illicit drugs market, which is handed over to the underground gangs and cartels, therefore not being submitted to any kind of regulation. The gangs and cartels are those who decide what they will produce and sell; what will be the toxic potential of the drugs; what cutting agents they will use; what price they will charge; where and to whom they will sell the drugs. Prohibition also hinders assistance and health services, either by ordering compulsory treatment, which besides being inefficient violate human rights, or by inhibiting the search of a voluntary treatment. Prohibition causes environmental harm, either directly by required manual drug crop eradication, or even worse, by aerial spraying of chemical herbicides, as has happened in Latin America, in the Andean region. Drug prohibition is driven by the provisions of the three UN conventions, which give the guidelines to the domestic laws of almost all countries of the world. These provisions introduce an arbitrary differentiation between the conduct of producers, sellers and users of the selected drugs that were made illegal (such as marijuana, cocaine or heroin) and the conduct of producers, sellers and users of other similar drugs that remain legal (like alcohol). The conduct of some producers, sellers and users are crimes, while the conduct of other producers, sellers and users are legal. Such an unequal treatment to absolutely similar activities is a clear violation of the principle of equality, according to which all persons shall be treated equally under the law. Many other principles guaranteed in declarations of human rights are systematically violated by the UN conventions and domestic drug laws. In effect, prohibition and its “war on drugs” are inconsistent with human rights. These are contradictory concepts. Wars and human rights are not compatible in any circumstances. The “war on drugs” is not truly a war against drugs. It is not a war against things. Like any other war, it is rather a war against people – the producers, sellers, and consumers of the arbitrarily selected substances that were made illegal. It is more properly a war against the most vulnerable among these producers, sellers and consumers. The “enemies” in this war are the poor, powerless, and marginalized people. The massive incarceration of African Americans in the United States1 reveals the primary target of the American drug war: to perpetuate discrimination based on the color of the skin, which earlier was enforced by slavery and the segregation system known as Jim Crow. Drug prohibition is also overcrowding Brazilian prisons. Brazil has now the fourth largest prison population in the world. Inmates sentenced for drug 1 In two decades, between 1980 and 2000, the number of incarcerated people soared from roughly 300,000 to more than 2 million (in December 2011, there were 2,239,800 people in prisons and jails in the United States). Following the declaration of the “war on drugs” in the early 1970s, the number of drug offenders incarcerated in the United States increased by more than 2,000 percent. African-Americans are incarcerated at substantially higher rates than whites, far out of proportion with their representation in the total population. Blacks constitute 13.5% of the population, but 37% of those arrested for drug violations are Black; over 42% of those in federal prisons, and almost 60% of those in state prisons for drug violations are Black. If we consider only African-American men, the imprisonment rate (716 inmates per 100,000 U.S. residents) increases to more than 4,000 inmates per 100,000 U.S. residents. Sources: Crime in the United States: FBI Uniform Crime Reports 2005; Bureau of Justice Statistics, US Department of Justice; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Summary Report 1998 (Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 1999); and Mauer, Marc. Americans Behind Bars: The International Use of Incarceration, 1992-1993, The Sentencing Project, September 1994, http://www.druglibrary.org/schaffer/other/sp/abb.htm. offenses are 27% of the Brazilian prison population. In the last 7 years, the number of inmates sentenced for drug offenses more than quadrupled.2 However, drug prohibition produces not only mass incarceration. Prohibition creates “crimes without victims,” but the “war on drugs”, as any other war, is lethal. In Mexico, the military offensive against the cartels unleashed an ongoing wave of violence that has killed more than 70,000 people since it was launched in December of 2006.3 Brazilian laws do not provide for the death penalty. However, as reported by Amnesty International, between January and September 2012, 804 people were killed by the police in the states of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo alone. This number is higher than the total of confirmed executions – 682 – in the 20 countries that carried out the death penalty in that whole year, except China.4 In the latest ten years, in the city of Rio de Janeiro, one out of five of all murders has been the result of summary executions during police operations in the poor communities known as favelas.5 Moreover, the “war on drugs” has brought back to the scene the “enforced disappearances” that were a characteristic of the twentieth century’s Latin American dictatorships. Both in Mexico and in Brazil, many people have disappeared in the latest years, probably killed either by the police or by drug dealers. It is time to put an end to the failed, harmful and bloody drug prohibition. It is not enough to decriminalize drug possession for personal use, or to legalize only some substances seen as “soft” drugs, like marijuana or the coca leaf. It is rather necessary to legalize – and therefore regulate – the production, supply and consumption of all drugs. 2 In December 2012, there were 548,003 people in prisons in Brazil (287 per 100,000 inhabitants). In 1995, there were 148,760 inmates in Brazilian prisons (92 per 100,000 inhabitants). In December 2005, there were 32,880 inmates sentenced for drug offenses; in December 2012, this number increased to 138,198 inmates. All data are from the Ministry of Justice of Brazil. 3 See the report of The Observer of 8 August 2010, when the death toll in México was still 28,000: http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2010/aug/08/drugs-legalise-mexico-california In early 2012, the death toll was 50,000: The Washington Post (02/01/2012) “In Mexico, 12,000 killed in drug violence in 2011”: http://articles.washingtonpost.com/2012-01-02/world/35441712_1_drug-violence-drugkillings-drug-gangs. In 2013, the number raised to 70,000: International Herald Tribune (08/03/2013): “Adding Absurdity to Tragedy”: http://latitude.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/03/08/a-memorial-in-mexico-city-adds-absurdity-totragedy/?ref=drugtrafficking. These are estimated figures. The lack of precise information suggests that, in reality, there may be much more deaths caused by the Mexican drug war. 4 21 countries carried out the death penalty in 2012, but the figures exclude China, where accurate information on the death penalty is still impossible to obtain)Amnesty International. Annual Report 2012; Death Sentences and Executions 2012. http://www.amnesty.org/en/region/brazil/report-2012 http://www.amnesty.org/en/death-penalty/death-sentences-and-executions-in-2012 5 Data can be found at Instituto de Segurança Pública – Governo do Estado do Rio de Janeiro http://www.isp.rj.gov.br The mere decriminalization maintains the illegality of the drug market, thus leaving untouched the most harmful consequences of drug prohibition and its war, such as violence; corruption; greater risks and harm to health and to the environment; deaths; mass incarceration; racism and other discrimination; humiliation, control and submission of the poor, powerless, and marginalized people; violation of principles guaranteed in the declarations of human rights and democratic constitutions. Only legalization will put an end to all these harmful consequences. To legalize drugs means to regulate and control them. All drugs, legal or illegal, may be dangerous. The more dangerous are the effects of a drug, the more reasons are to legalize its production, supply and consumption, because one cannot control or regulate what is illegal. Legalizing all drugs will give back to the State the power to regulate, control, limit and tax the production, supply and consumption of these substances. Besides putting an end to the risks, harm and pain caused by prohibition, legalization is the only way to reduce the dangers caused by drug use. Freed from prohibition, drugs will cause less harm. The end of the “war on drugs” and the replacement of prohibition with a system of legalized regulation of all drugs are the most urgent measures to reduce violence, social harm, pain, and injustice.