chapter two - University of Ilorin

advertisement

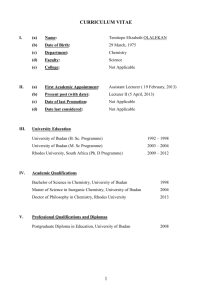

THE CHANGING ROLE OF THE TRADITIONAL POLITICAL INSTITUTION IN IBADAN IN THE TWENTIETH (20 ) CENTURY. TH BY ADENIJI ABIOLA TOSIN A PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF BACHELOR OF ARTS, UNIVERSITY OF ILORIN, ILORIN, NIGERIA. i CERTIFICATION This is to certify that this project was carried out by Adeniji Abiola Tosin and has been read and approved as meeting parts of the requirements of the faculty of Arts, University of Ilorin for the Award of Bachelor of Arts in History and International Studies. ..…………………………… Dr. S.Y Omoiya Project Supervisor …………………..……….. Date ..…………………………… Dr. Sam. Aghalino Head of Department …………………..……….. Date ..…………………………… External Supervisor …………………..……….. Date ii DEDICATION This Research work is dedicated to the Almighty God, the Author and Finisher of my faith. It is He who see me through my Academic pursuit, all glory and adoration belong to Him alone. Also, to my precious and wonderful father, Deacon Sunday Adebayo Adeniji for his fatherly role and to the memory of my late mother, Mrs Esther Oluwayemisi Temilade Adeniji (Nee Banigbade), who saw me started but could not see me finishing my academic pursuit, whose sad event occurred on the 2nd of January, 2009. May Her Gentle Soul Rest in Perfect Peace (Amen). iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I thank the Almighty God for his faithfulness in my life. I shall forever be indebted to Him. I am also indebted to my supervisor, Dr. S.Y. Omoiya who devoted his time to read through the essay and also for his sincere advice throughout the process of the production of this essay. He has been very fatherly.” Special thanks are due to all my informants for their advice and assistance, I am particularly grateful to the member and staff of the National Archives, Ibadan (N.A.I), most especially Mrs. Omoshule, Mr. Iyiola of the Department of History, University of Ibadan. The staff and management of the Research units, University of Ibadan Library (Kenneth Dike) for their materials and useful suggestions and for the loans of other books. My major appreciation goes to my father, Deacon Sunday Adebayo Adeniji for his support, financially and his prayer throughout my academic pursuit. I bless God for giving me such a wonderful father and I pray that God will give him long life to reap the fruit of his iv labour. I will also extend my appreciation to my Siblings, Oluwatayo Adeniji, Oluwabukunmi Adeniji and Oluwatobilola Adeniji. I love you all. I am short of words to express my profound gratitude to my guardian in Ilorin, Mr and Mrs John Adewale Ogunrinde (United Kingdom), for their support both financially and materially and also for accommodating me throughout my academic pursuit in Ilorin and for taking me as their me as their own biological daughter. I say than you. I also appreciate the love and care shown to me by my friends and loved ones, Okolo Julianah, Ibiyemi Akinpeloye, Toyin Ogundola, Tola and Femi Ademuyiwa, Dayo and Bose Ajewole, Oyewumi Oyedokun, Asiat Bello, Obagho loveth, Farouq Muinat, Uncle Rotimi, Uzomah Ukpabi, Falola Olasunkanmi. You are all a friend indeed. Finally, my utmost thanks goes to my fiancé Adedayo Ebenezer Akinduro, for his care, love, support and devotion on which I liger. “I love you”. I love you all, Thanks you. ADENIJI ABIOLA TOSIN v CHAPTERIZATION CHAPTER ONE 1.1 Statement of the problem 1.2 Objective of the Study 1.3 Scope of the Study 1.4 Research Methodology 1.5 Literature Review Notes and References CHAPTER TWO 2.1 The Evaluation of Ibadan and its Political Institution 2.2 The Establishment of a New Government in Ibadan 2.3 The Hierarchical Structure of the Political Institution 2.4 Ibadan under Colonial Rule 2.5 The Emergency of Olubadan Title and His Coordinating Roles. Notes and References vi CHAPTER THREE 3.1 New Socio-Political Structure in Ibadan 3.2 Impact of British Intervention in the 19th Century Warfare 3.3 Role of Ibadan in the Extension of British Influence in the Interior 3.4 The status of Ibadan in the Political Order Notes and References CHAPTER FOUR 4.1 Ibadan as the Regional Capital 4.2 Reflections on the Contributions of Ibadan Indigenes 4.3 Impact of Provision of Basic Amenities 4.4 The Economic Order in Ibadan 4.5 Impacts of Politics on Ibadan 4.6 Conclusion Notes and References Bibliography vii CHAPTER ONE 1.1 STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM The need to examine the changing role of Traditional Political Institution in Ibadan is considered to complement the existing literature on Ibadan as a polity. Indeed, various aspects of Ibadan history have been documented and by different scholar but a sequential appraisal of the changes witnessed by the Traditional Political Institution have been treated in passing. The desire to dedicate this project to the issue is to further illuminate an important aspect of Ibadan history. Even though, the project focuses on the 20th century. The events before the period, where the Traditional Institution played prominent role, will be accommodated to provide an holistic appraisal of the changes witnessed by the Traditional Political Institution at Ibadan. 1 1.2 OBJECTIVE OF THE STUDY The objective of writing on this topic is to examine the different changes that occurred within the Traditional Political Institution of Ibadan in the 20th century. Generally, change is the transformation of an event, a system, an object or a process. It may either be qualitative or quantitative or both. The concern of this essay project is primarily with the transformation and modification of an important event in the Institution of Ibadan society. These Institutions or units are the offices of the Traditional Ruler in Ibadan which bestows an identifiable status on the incumbent. Although, many scholars both Historians and non-Historians have given considerable attention to the Period Colonial Administration, not only in Ibadan but also in the whole of Yoruba land. 2 Yet, there is no work which has studied the theme of this essay in the context of the changing role of the Traditional Political Institution of Ibadan in the 20th century. Finally, it is the desire to investigate what changes that occurred in the Traditional Political Institution of Ibadan in the 20th century in general. 1.3 SCOPE OF THE STUDY This study focuses on the events of the 20th century, that is to say from 1900-1999 but as an historical study, the need to apprise the period before the period of focus will provide necessary information that will illuminate the understanding of Ibadan history. To follow the period before 20th century, a full focus will be on the period to appraise the changes recorded in both the status and role of the Traditional Political Institution in Ibadan. The fact that the 20th century covered the period of colonial administration, the period when Nigeria became independent and 3 under civil and military administrations, study of this topic will provide a better understanding of Ibadan history. 1.4 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY / PROBLEM As an historical documentation on a city like Ibadan, that is known to be the largest city in West Africa, a multi-disciplinary research methodology was adopted. The study began with the study of available literature on various aspects of Ibadan history. This was followed with the visit to the National Archive at Ibadan and finally oral data collection was undertaken. Indeed, Questionnaires were prepared to obtain information on data based requirements. Indeed, the experience is worth while. A lot of informant’s were not readily available and others gave several promises before they eventually made themselves available. Finally, the land size of Ibadan, actually constituted another problem which directly overstress my financial provisions. 4 1.5 LITERATURE REVIEW Since much has been written on the changes in the Traditional Political Institution in Ibadanland, they provide a good base for this study. For instance, books consulted like B.A. Awe: “The Rise of Ibadan as a Yoruba Power in the Nineteenth Century” and S. Johnson: “The History of the Yorubas” which agreed on the fact that Ibadan town was founded as a war camp in the 19th century and also, they agreed on the pre-colonial political setup of Ibadan based, as it were on the military. According to P.C. Lloyd in his book titled “The city of Ibadan”, Ibadan, that “ethnographic anomaly” as Peter Lloyd tightly terms the Yoruba cities, unique as an Obaless Yoruba city which clawed its way to the top eluting the enables and sometimes mindless nineteenth century Yoruba wars, Ibadan today is the capital of the Western province of Nigeria, the largest city (though smaller than greater Lagos according to A.L. Mabogunje) in the country and one of the largest black African cities on the continent. 5 Also, according to I.B. Akinyele’s book titled “The outline History of Ibadan”, Ibadan was founded in the in the 16th century,. Around 1820, an army of Egba, Ijebu, Ife and Oyo people won the town during their wars with the Fulanis. After a struggle between the victors, the Oyo gained control in 1829. A system where the Baale line (civic) and Balogun Isoriki line (military) shared power was established by 1851, subject to a traditional council resenting both lines. Akogun Lekan Alabi’s work titled “Ibadan Chieftaincy System”, stressed the point on the recognition of the Royal Family who are expected to be headed by a male member called “Mogaji”. Anyone selected or elected rather to be the Mogaji of his family must have the majority support of the family, but a unanimous support is ideal. J.F.Ade Ajayi’s book titled “Background to Exalted Olubadan’s Throne” also gave a valuable information which shed more lights on the instability occasioned by the incessant wars which was one of the recurring themes in the History of Yorubaland in the Nineteenth 6 century, and it was out of this morbid situation that Ibadan grew. He made use of oral Tradition that speak of three Ibadan. First and foremost, Ibadan came into existence in 1829 when Lagelu, the Jagun (commander-in-Chief) of Ife and Yoruba’s generalissimo, left Ile-Ife with a handful of people from Ife, Oyo, and Ijebu to found a new city, Eba Odan, which literally means ‘between the forest and plains;. According to HRH Sir Isaac Babalola Akinyele, the late Olubadan (king) of Ibadan (Olu Ibadan means Lord of Ibadan), in his authoritative book on the history of Ibadan, “Iwe Itan Ibadan”, printed in 1911, the first city was destroyed due to an incident at an Egungun (masquerade) festival when an Egungun was accidentally disrobed and derisively mocked by women and children in an open market place full of people. In Yorubaland, it was an abomination for women to look an Egungun in the eye because the Egunguns were considered to be the dead forefathers who returned to the earth each year to bless their progeny. When the news 7 reached Sango, the then Alaafin of Oyo, he commanded that Eba Odan be destroyed for committing such abominable act. Secondly, Ibadan was historically an Egba town. The Egba occupants were forced to leave the town and moved to present day Abeokuta under the leadership of Sodeke when the surge of Oyo refugees flocked into the towns as an aftermath of the fall of Oyo kingdom. Ibadan grew into an impressive and sprawling urban center so much that by the end of 1829, Ibadan dominated the Yoruba region militarily, politically and economically. The military sanctuary expanded even further when refugees began attiring in large numbers from northern Oyo following raids by Fulani warrior. After losing the northern portion of their region to the marauding Fulanis, many Oyo indigenes retreated deeper into the Ibadan environs. Thirdly, Ibadan according to him represented the culmination of certain development which started from the old Oyo empire. He asserted that the Fulani caliphate attempted to expend further into the 8 Southern region of modern-day Nigeria, but was decisively defeated by the armies of Ibadan in 1840. This work also examines the mutation of an institution in Ibadan society unit the office of the ruler nitrous of his role, responsibility and public image. The Ibadan Ruler in the colonial period was known as Baale and then he was nothing more than a primus Inter Pare (First Among Equal) at home, because of the Oligardiy rafure of the Ibadan Government. With the establishment of a colonial state, the Bale was curtailed both within and without Ibadan in the Twentieth century which did not satisfy his desire for more power. Ruth Watson, ‘Civil Disorder is the Disease of Ibadan’: chieftaincy and civic culture in a Yoruba city. This book captures the complicated process of acquiring titles and becoming a chief in a competitive political environment where many individuals defined their lifetime ambition as acquiring honour through chieftaincy. More importantly, the book reveals how these titles actually ascribed civic status. The book shows how a civic political culture had to be 9 created, and how powerful figures operated within it. Without a civic community, there would be no chiefs. And without chiefs, one may argue, a civic community of the type described in this book could not have been created. Merging two eras in history the Pre-Colonial and Colonial. Watson elaborates upon the relationship between city politics and chiefs. 10 REFERENCES B.A. Awe, “The Rise of Ibadan as a Yoruba Power in the Nineteenth Century”, Ph.D Thesis Oxford University Press, July 1964, PP. 76-120. G.O. Ogunremi (ed) Ibadan, “An Historical Cultural and SocioEconomic Study of an African City, Ibadan. I.B. Akinyele, “The Outlines of Ibadan History”. Lagos, Alebiosu Printing Press 1946-PP6. J.A. Atanda, “The new Oyo Empire”, Ibadan 1968, Ph.D Thesis. PP 107-215. J.F. Ade Ajayi, and B. Ikara, “Evolution of Political Culture in Nigeria”, Ibadan University Press Limited. PP 206-217. Jenkins .G.D., “Politics in Ibadan”, Ph.D. Thesis (Evanston Illinois, June 1965) PP 48-55 Ruth Watson, “Civil Disorder is the Disease of Ibadan”: Chieftaincy and civic culture in a Yoruba city. Oxford and Athens: James Currey and Ohio University Press. PP 180. 11 P.C. Lloyd, A.L. Mabogunje, and B. Awe, “The city of Ibadan”, Cambridge: The University Press. 1967. PP 280. S. Johnson, “The History of the Yorubas” Lagos C.M.S. Nigerian, Printed in 1951. PP 638-639. Toyin Falola, “The Political System of Ibadan in the Twentieth Century. PP 159-165. 12 CHAPTER TWO 2.1 THE EVOLUTION OF IBADAN AND ITS POLITICAL INSTITUTION Ibadan is located in South – Western Nigeria. It is the capital of Oyo State, and is reputed to be the largest indigenous City in Africa, South of the Sahara. Ibadan had been the centre of administration of the old Western Region, Nigeria Since the days of the British Colonial rule. It is situated 78 miles inland from Lagos, and is a prominent transit point between the coastal region and the areas to the north. Parts of the City’s ancient Protective walls still stand till today, and its population is estimated to be about 3,800,000 according to 2006 estimates. The principal inhabitants of the city are the Yoruba. Ibadan, surrounded by seven hills, is the second largest city in Nigeria. It came into existence when bands of Yoruba renegades following the collapse of the Yoruba Oyo Empire, began settling in the area towards the end of the 18th century; attracted by its strategic location between the forests and the plains. Its Pre-Colonial history 13 centred on militarism, imperialism and violence. The military sanctuary expanded even further when refugees began arriving in large numbers from Northern Oyo following raids by Fulani Warriors. Ibadan grew into an impressive and sprawling urban center so much that by the end of 1829, Ibadan dominated the Yoruba region militarily, politically and economically. However, the area became a British protectorate in 1893. By then the population had swelled to 120,000. The British developed their new colony to facilitate their commercial activities in the area, and Ibadan shortly grew into the major trading center that it is today. The colonizers also developed the academic infrastructure of the city. The first University to be set up in Nigeria was the University of Ibadan (established as a college of the University of London when it was founded in 1948, and later converted into an autonomous University in 1962). The most probable date of the founding of Ibadan is 1829, when the abandoned settlement of Ibadan was reoccupied 14 by the allied forces of Ijebu, Ife and Oyo, hence, it came to be regarded as “a war encampment’ of the town of warriors. From the Onward, Ibadan grew unimportance and has served as the administrative centre for the whole of Southern Nigeria (19461951). And as the capital of the Western Region (1951-1967). After this period, the city’s region started to shrink, to cover just the Western Region (1963-1967); Western state and old Oyo State (1976-1991), before the creation of Osun State, (1976-1991). It has been the capital of present Oyo State since 1991. The Political Status of the city has influenced other aspect of its development. One of which is the reminiscence of colonial administration. The Government Secretariat at Agodi and the Government Reservation Areas (GRAs) A at Agodi, Jesicho and Onireke are relice of that era. The grid pattern of the residential layout of Oke-Bola and Oke-Ado is also associated with its activities. 15 2.2 THE ESTABLISHMENT OF A NEW GOVERNMENT IN IBADAN Historically, two factors led to the emergence of Ibadan as a Yoruba town in the 19th century, they were the Owu war and the fall of the old Oyo Empire. Prior to the 1820’s, Ibadan was a small Egba village and it was the fall of the old Oyo Empire and the Owu war that changed its fortune from a village to a town. The old Oyo Empire which had been declining since the eighteenth century fell to the Fulani jihadists in 1837 and the headquarters of the empire was laid to ruin. The fall of the empire and the constant riots and attacks of the Fulani jihadists led to the flight of the Oyo Yoruba’s South – West wards to Shaki, Igboho, Iseyin and South Wards to Ijaye and Egbaland and South East Wards to Owu and Ile-Ife areas. The Oyo refugees who fled South east wards could not settle down like their counter parts who fled South Wards and South West Wards. This was because, on their arrival, they met with war between Ile-Ife and Owu that is, the Owu wars. The Oyo refugees adapted to the 16 situation and joined the forces of the Ife against Owu, with the support of the Ijebus, Ife defeated Owu. Moreover, after this war, Ife soldiers and ijebu soldiers went home but the Oyo refugees had no except place to settle. Hence, they decided on plunder. Their target was Egba villages and towns, they were soon joined in this plunder by some Ijebu and Ife soldiers. Many of the Egba villages and towns were attacked, plundered and set on fire. Of all the villages plundered by the victorious allies, only Ibadan was not destroyed, so this marauding band hastily occupied the place. Thus, Ibadan was again repeopled not by its former inhabitants, but by a band of warriors and marauders consisting of the Oyos, Ifes and Ijebus. No sooner had the warriors and soldiers settled down in Ibadan, then the civil war broke out amongst them, each groups struggling for leadership. At long last, the Oyos became victorious over their Ife rivals. The defect of the Ife and the death of their leader Maye encouraged more Oyo refugees to dominate Ibadan. Thus, Ibadan became a 17 predominantly Oyo proper town. Since Ibadan was originally a war camp, and unlike old Oyo empire not fettered by any tradition and convention, the town attracted in particular young men eager for adventure and quick military distinction. Therefore, apart from the Oyo refugees, people from all parts of Yorubaland came to settle down in Ibadan. At this time, it was realized by all the residents that if they intended to make Ibadan their home, a form of government had to be set up. Since Ibadan owed its rise and the circumstances of its been repopulated to warfare, the administrative and political institution of Ibadan could not but reflects the military. As a result of this, a type of government was set up which could be described as a military oligarchy. With a new start in politics, Ibadan rejected the constitutional pattern of other Yoruba towns based on sacred and hereditary monarchy. Instead, it gave political authority to men who according to Jenkins showed the qualities of bravery, wealth, leadership, youthful vigour and experience which the city need in its early difficult years. After the death of Maye, Oluyedun 18 was made the Are-ona-kakanfo and head of the Ibadans. The Kakanfo was a military title and showed the importance of the military. Lakanle became the Otun-kakanfo and Oluyole became the Osi-kakanfo. There are other titles like Ashipa-kakanfo, Ekerinkakanfo, Ekarun, Are-Abese and Sarumi etc. Labosinde was made the Oluwo of Ibadan and Baba’sale. All these titles were military titles except the last one. This type of administrative system showed the role that warfare was going to play in the history of Ibadan in 19th century. Looking at these types of political set up, the great anomaly that one finds when one compares it with what operated in some other Yoruba towns in the 19th century was the absence of an Oba or Crowned head. The reason for this was that none of the early warriors was a royal prince of sufficient status to establish a royal rule. Oluyedun, the Oyo ruler was a son of Afonja, he thus had high prestige but his father had never become a crowned ruler. 19 Similarly, Oluyole later to rule Ibadan as Bashorun was only related maternally to the Alafin of Oyo and hence he was not qualified to be called royal prince. These political institutions which were mainly military title persisted in Ibadan to this day, but as time went on, modifications were made, these modifications started with Oluyole who became the Bale in 1830. According to I.B. Akinyele, Oluyole was credited for “organizing Ibadan ceased to be a war camp”. The chieftaincy titles of Ibadan was later divided into two major lines; the military and the civil lines. Under these two categories, there were five separate line of chiefs. Namely:- The Bale, Balogun, Seriki, Sarumi and the Iyalode. At the apex of the main military line was the Balogun and at the top of the main civil line was the Bale. Below these main title holders, that is, the Bale and the Balogun was the subordinate chief bearing titles significant to their positions beside their leaders on the battlefield and their sitting position at the council meeting. The second military line was headed by the Seriki which was made up of young warriors of 20 less experience and the second civil line was headed by Iyalode which was to represent womens interests. Thus, the Bale’s line, the Balogun’s line and the Seriki’s line respectively were the most important and the titles were not hereditary. The most important qualification for these chieftaincy titles was a man’s merit as a soldier, whereas in the case of the civil line, the main qualification was simply personal merit or contribution to the development of the town. There existed within these lines of chieftaincy titles a system of promotion from the lowest to the highest rank either of the Bale or the Balogun. There are other qualifications for attaining a title, for instance, an aspirant had to observe certain forms of behaviour expected of all chiefs. In general, aspirant must perform patriotic duties to the benefit of the town. Also, a man had to be influential among people in high ranking positions and he needs to have large number of groups of followers who should be able to plead his cause readily and frequently. 21 2.3 THE HIERARCHICAL STRUCTURE OF THE POLITICAL INSTITUTION Ibadan was a Republic and its political and administrative structure followed an hierarchical pattern. At the bottom of the system, there was a government at the lineage level. The lineage refers to the descendants of a kinship groups. Also, at the apex of the lineage was a Mogaji with hierarchical judicial system. The lineage courts had initial jurisdiction over marriage and divorce, land matters, petty quarrels and all matters in which both contestants were from the same village. The judicial procedure in the lineage was informal, since its main purpose was for the maintenance of peace in the lineage. Disputes beyond the lineage court and involving members of the other compounds were dealt with at the chief’s courts. There was a central administrative council which consisted of the Bale and the Balogun, in addition were the next six chiefs from each of their respective lines. This included the Seriki and Iyalode. A sum total of 22 sixteen chiefs made up the council. The Bale was the head of the government and the post was won usually by an ex-Balogun. It is important to note that, the post of a Bale was not hereditary. Theoretically, actual leadership rested with the Bale, and political decisions which did not involve wars were made by the civil chiefs. In practice however, political power rested with the military chiefs. This is not surprising, considering the fact that Ibadan was a political society. Secondly, only the military chiefs as a result of their profession could maintain and control a large number of followers on which the prestige of a chief depended in Ibadan. The reason why the bale could not wield effective power as the military chiefs was that the post of a Bale was usually taken by old men who could no longer make any distinguished military contributions. The government of Ibadan before the British arrival involved the Bale in council. The council had certain functions it used to perform on its own in the administration of the town and the lineages. The 23 council was expected to direct military policy but the army was usually raised through the lineages. Among the roles performed by the chiefs are decisions on questions of security, and customs collection at the town gates. The actual collection of customs was however supervised by the lineages whose compounds were located at the town gates. The council was responsible for appointing new chiefs and for promoting chiefs to higher posts and also, the appointment of a new Bale. It is pertinent to note that the decisions of the council are final in any question it deals with and at any level. Another important role of the council of chiefs was in its capacity as the supreme court of the town, since minor case were settled in the lineage courts, the chiefs court really served as an appeal court for the lineage, it could either be the Bale’s court or the court of any chief under them. In a very interacting manner, the council posed as an “arbitrator, mediator and coordinator” among the other institutions of the society. The council relied on the other institution of the society for the execution of its 24 policies. Since there was at no time a central treasury independent of the council, the expenses of the Bale’s administration were derived from the city’s treasury. There was no special council meeting room or court room, all being situated in the reigning Bale’s house. Furthermore, the Bale’s household consisted of messengers, intermediaries and ambassadors. On the death of a Bale, all the physical facilities, treasury and the civil service of his administration were absorbed by his household, and a new one will be effectively succeeded by a successor. By far, the most important function of the council however lies in its capacity as the supreme court of the town. As it had been mentioned earlier, minor cases within the lineage were settled in the lineage or compound court. The final appeal court of the town was the weekly council court which used to meet on Monday s with the Bale as president. The council court could sit as appeal court for the lower courts of the lineage and the chief’s court but it had original jurisdiction in cases with political implications and those 25 involving the death penalty such as major thefts, murder or adultery with a chief’s wife. In carrying out its judicial function, the council had no jail, no policemen and no law enforcement agents of its own, as such it had no other institutions of the society like the Ogboni, and the Ogboni had the final say in a case. For instance, where public sentiment was not fully in accord with the judicial decision. Another method of compelling obedience to the council’s decision was in general plundering and devastation. For example, if the council had any case to decide the death of a chief, his followers might like to council might declare the chief’s compound open to the general public. His compound will be broken into and be devastated. The chief had to choose between having his compound devastated or committing suicide. There was no fixed official residence or Afin for the Bale. From this description of the hierarchical structure of the political institution of Ibadan, one notices that there was a remarkable difference between the government of Ibadan and that of most of the 26 other Yoruba town. Formerly a war camp and populated mainly by warriors, Ibadan developed a type of administrative structure and political institutions suitable only for a military society. This was an open and democratic society, in which there was no group of people or society that wielded great and unrestrained power in the administration of Ibadan like the Oyomesi in Oyo ile, the Ogboni or Osugbo in Abeokuta and Ijebu respectively. The Ogboni was active in Ibadan but not as a regular part of the political structure, it was only called in when its services were needed especially in the administration of justice and peace. To this end, this unique type of administrative system based on the military operated in Ibadan unit the eve of the imposition of colonial rule. However, when Ibadan came under the British rule in 1893 and with the imposition of peace on Yorubaland, and the system of indirect rule, changes began to occur in the political administration of the chieftaincy institution in Ibadan. An executive council of senior chiefs was established in 1897 with the Resident 27 officer as its president. The Oja’ba Native Administrative Court was opened in 1903 and the chiefs began to lose their customary rights to private jurisdiction. 2.4 IBADA UNDER COLONIAL RULE As a result of the Agreement of August 1893, Ibadan came under British colonial rule and the effects of the impact of colonialism on the political institutions of Ibadan were great. These effects were brought about by certain administrative policies of the British colonial government. In the pre-colonial period as it has been mentioned earlier on, the political institutions of Ibadan were a reflection of the military society which Ibadan was. One of the most important considerations in the appointment of chiefs was their achievement on the battlefield. In the council, the war chiefs on the Balogun and Seriki lines were more influential than the civil chiefs on the Bale’s line. The system of attaining chieftaincy through performance on the battlefield accounted for much of the Ibadan constant warfare in the 19th century. With a government which encouraged military exploits and a 28 people who found in military activities a means of climbing the ladder of the political hierarchy of the city, also with a very strong army, Ibadan by the middle of the nineteenth century had emerged as a great imperial power in Yorubaland. However, in 1886, the British government in Lagos had intervened to put an end to the endemic warfare in Yorubaland by the treaty of peace, friendship and commerce. This was not the end of warfare in Yorubaland. The death blow against warfare was struck in 1893 when Governor Carter sent captain Bower of the Ijebu-Ode campaign as the president at Ibadan and the Traveling commissioner to supervise the peace in Yorubaland. The stationing of Bower in Ibadan by the British was not surprising. The British realized that Ibadan was the most powerful militarily and the most aggressive power in Yorubaland before colonial rule. The imposition of peace in Yorubaland greatly affected the political institution of Ibadan. ‘The Ibadan army never took of field again’. As the political institution of Ibadan had been fashioned to suit 29 a military society, the new peace time in Ibadan history affected those institutions. First, the position of the Bale. In Ibadan Political tradition, the Bale as it has been previously mentioned was supposed to be an ex-Balogun. But in reality no Balogun had ever succeeded a Bale because according to I.B. Akinyele every Balogun wanted to distinguish himself in a battle before he became the Bale and in their attempt to fulfill their desire they died. Thus it was usually the immediate subordinate of the Balogun like the Otun Balogun or Balogun that became the Bale. However, in 1893 as a result of the imposition of peace, Akintola the Balogun became the first Balogun to out live the Bale and to be eligible for Baleship. However in 1895 Akintola declined the post of Bale, because he and the young chiefs under him still entertained the hope that the white men would soon go. “So that he would be able to carry the title of Balogun to war”. As a result of Akintola’s decline to take the post of Bale, the position passed to Oshuntoki. This as the first time an Otun Bale would become a Bale in Ibadan. An interesting outcome of the end of 30 warfare on the political institutions of Ibadan can be seen in an occurrence in 1904. When Fajimi the successor of Oshuntoki died in 1904, Kongi the Balogun wanted to become the Bale but he was opposed by the chiefs on the ground that “no Balogun had ever become the Bale”. This was an irony in the history of the political institutions of Ibadan. It was indeed a fact that no Balogun had ever become bale in Ibadan but the Bale had always been a chief from the Balogun’s line. However, from 1895 Akinyele commented that “it became the fashion that the Otun Bale should become the Bale”. This was a situation brought about not by direct interference of the British in the political institutions of Ibadan, but rather it was an indirect result of the imposition of peace on a military society by the British. Also, with the end of the inter-tribal wars, the consideration of a man’s valour on the battlefield as a qualification for appointing him as a chief or promoting him in the chieftaincy hierarchy declined. Wealth succeeded as a qualification for chieftaincy instead of valour on the 31 battlefield. According to I.B. Akinyele “men began to use their riches to fight for title”. Moreover, from 1912 – 1913 when captain Ross and the Alafin of Oyo virtually became of Ibadan were appointed, promoted and dismissed by the Alafin. The chiefs now sought promotion by intrigue each chief trying to dislodge the other by bringing them into the black book of Captain Ross and the Alafin so as to secure the position of the dispossessed. Examples of chief who were dislodge in this way were Bale Irefin who was deposed in 1914, Shittu in 1925 and Balogun Ola in 1918. Thus the imposition of peace in Yourbaland by the British in 1893 brought changes in the political institutions of Ibadan. But these changes far from being precautionary, had a modifying effect on the political institutions of Ibadan. The political structure still remained the same. There were civil and military chiefs at least in appointing and promoting chiefs and the function of some of the chiefs. 32 2.5 THE EMERGENCY OF OLUBADAN TITLED AND HIS COORDINATING ROLES From 1906-1931 Captains Ross had pursued a policy of making Oyo the sole administrator of Ibadan and the rest of the Oyo provinces. And as it has been pointed out, this policy brought important changes in the political institution. From 1931, however changes of opinion were introduced about the policy of indirect rule in Nigeria. This change of opinion was due to a number of factors. First in 1931, Captain Ross had retired as the Resident of Oyo province and he had left Nigeria for good. Secondly, the appointment of Sir Cameron as the Governor of Nigeria was important for the review of indirect rule. Sir Cameron had a liberal view of indirect rule which was to associate more people with the Native and to base indirect rule on the consent of the people over whom such authority would be exercised. The third factor was the appointment of Mr. H.C. Ward Prince like Sir Cameron had a liberal view of indirect rule and he believed that jurisdiction of a native authority should be based on 33 the consent of the people and on this basis he pressed that the power of the Alafin on Ibadan should be broken. Apart from the review of the indirect rule in the 1930’s, other changes were occurring which had great impact on the political institutions of Ibadan. Ibadan in the 1930 was fast becoming an urban and modern city. The economy had expanded, cash crops were developed. The Christian community in Ibadan which used to be mainly the C.M.S. mission established by David Hinderer in the 1850’s had diversified greatly and the Roman Catholics, the Methodists, the Baptist and African Churches assumed increasing importance. An increasing number of schools sprang up for Muslims and Christians. The first grammar school, the Ibadan Grammar School had been founded in 1913 by the Ibadan District Council and the C.M.S. so by the beginning of the twentieth had grown and had turned out a number of educated Ibadans. Among whom were Rev. Alexander Akinyele, his brother Isaac Akinyele, D.A. Obasa and Rev. D.A. Williams. In 1914 the leaders of the Christian community 34 including I.B. Akinyele and Alexander Akinyele had formed a society known as Egbe Agba Otun, an historical and cultural society. During the ‘reign’ of Ross in Ibadan the society went underground because of Ross’s hostility to the educated elites in Ibadan. In 1930, the Ibadan progressive union was formed and it grew out of the Egbe Agba Otun. The Ibadan progressive union (I.P.U) was largely composed of educated Christians who sought to effect reform by agitating what was described as Oyo oppression. The I.P.U was fortunate to have at the helm of affairs in Oyo province Mr. H.C. Ward Price the Resident who shared its view that Ibadan should be set free from Oyo oppression. With the influence of the I.P.U. Mr H.C. Ward Price brought a lot of changes into the Oyo province which affected the political institution of Ibadan. When Ward Prince returned from his first leave, the I.P.U. asked for three gifts, water, electricity and the return of education councilors to the council. Educated Councilors had been elected into the council by Resident Elgee in 1903 but they had been dismissed by Ross. The request of the I.P.U. for the return 35 of educated councilors into the council was granted and two I.P.U. candidates Isaac Akinyele and J.O. Aboderin were accepted by the chiefs. Importantly, through the influence of the I.P.U. on Resident H.C. Ward Prince, the break up of the Oyo Empire was hastened and the break up occurred in 1934. The result of the breakup was that Ibadan became a Native Authority, independent of the Alafin of Oyo. Another success won by the I.P.U. was that they succeeded in their struggle to being on equal footing with Oyo by having the title of the Bale changed to Olubadan of Ibadan meaning “head of Ibadan or Lord of Ibadan” in 1936. This was a significant change in the position of the Bale now Olubadan who had now been elevated above the other chiefs in the council both in status and in authority. While these changes were taking place in the composition of the council and the status of the Bale, changes were also taking place in the chieftaincy system of Ibadan. According to I.B. Akinyele, in his book “Outline of Ibadan History”, he said, “we are thankful to 36 God that the present Olubadan realized the importance of good character. He showed his appreciation by raising some of the educated sons of the soil to chieftaincy”. The new educated chiefs were Salami Agbaje who became Are Alasa, Mr I.B. Akinyele an excouncillor became the Asaju Balogun and he was later to become the first educated Olubadan of Ibadan, and J.O. Aboderin became the Akogun of Ibadan. The appointment of educated men as chiefs by the Oulbadan of Ibadan was an important development in the chieftaincy system. It should that the Oluadan was identifying the political institution of Ibadan with the educational pre-colonial policy by which chiefs were appointed principally on the basis of their performance on the battlefield, the appointment of the education elite to chieftaincy position was a great change. Also, the Olubadan has the sweeping powers to depose or peg a chief, irrespective of the person’s position on the chieftaincy line. By implication, high chiefs on the lower cadre could be promoted above a high chief whose position was pegged. Even when forgiven in the 37 event that he was penitent, the promotion would not be reversed while the offending high chief served his punishment. For instance, during the reign of Oba Fijabi II, between 1948 and 1952, a wealthy BAlogun, who was next to Olubadan, was said to have had his chieftaincy pegged. About the same time, a holder of the title of OsiOlubadan was also hammered for acts of disloyalty to the cause of Ibadanland, an offence regarded as treasonable felony. To this end, Oba Ognudipe, the 39th Olubadan, ascended the throne on 7 May 1999 and died in 2007 at the age of 87. He was succeeded by Oba Samuel Odulana, 93, Odugade 1. Although the role is now largely symbolic, the Olubadan is still an influential figure and is not hesitant to attack local political leaders on issues such as violence, corruption and lack of true democracy in the region. LIST OF OLUBADAN Ba’ale Maye Okunade (1820-1830) Ba’ale Oluyedun Ba’ale Lakanle 38 Bashorun Oluyole 1850 Ba’ale Oderiola 1850 Ba’ale Oyeshile Olugbode 1815-1864 Ba’ale Ibikunle 1864-1865 Bashorun Ogunmola 1865-1867 Ba’ale Akere 1 1867-1870 Ba’ale Orowusi 1870-1871 Are Ona Kakanfo Obadoke Latosa 1871-1885 Ba’ale Ajayi Osungbekun 1885-1893 Ba’ale Fijabi 1 1893-1895 Ba’ale Oshuntoki 1895-1897 Ba’ale Fajinmi 1897-1902 Ba’ale Mosaderin 1902-1904 Ba’ale Dada Opadare 1904-1907 Ba’ale Sunmonu Apampa 1907-1910 Ba’ale Akintayo Awanibaku Elenpe 1910-1912 Ba’ale Irefin 1912-1914 39 Ba’ale Shittu Latosa (Son of Are Latosa) 1914-1925 Ba’ale Oyewole Foko 1925-1929 Olubadan Okunola Abass 1930-1946 (1st Olubadan) Olubadan Akere 1 1946 Olubadan Oyetunde 1 1946 Olubadan Akintunde Bioku 1947-1948 Olubadan Fijabi II 1948-1952 Olubadan Alli Iwo 1952 Olubadan Apete 1952-1955 Oba Isaac Babalola Akinyele 1955-1964 Oba Yesufu Kobiowu July 1964-December 1964 Oba Salawu Akanni Aminu 1965-1971 Oba Shittu Akinola Oyetunde II 1971-1976 Oba Gbadamosi Akanbi Adebimpe 1967-1977 Oba Daniel ‘Tayo Akinbiyi 1977-1982 Oba Yesufu Oloyede Asanike 1 1982-1994 Oba Emmanuel Adegboyega Operinde 1 1994-1999 40 Oba Yunusa Ogundipe Arapasowu 1 1999-2007 Oba Samuel Odulana Odugade 1 2007-present 41 REFERENCES Abdullahi Smith, “A little new light on the collapse of the Alafinate of Yoruba”. PP 18-21 Akinyele I.B. “Iwe Itan Ibadan”, James Townsend and Sons Limited, England 1946. PP 60-66 J.A. Atanda, “An Introduction to Yoruba Histology”, Ibadan University Press. PP 18-22 K.B.C. Onwubiko, History of West Africa from 1000 to Present day. PP 85-89. J.A. Atanda, “Indirect rule in western Nigeria” 1594-1934. PP 66-70 Toyin Falola, “The Political economy of a Pre-Canonical African State”, Ibadan 1830-1900 Obaro Ikhime, “A Groundwork of Nigerian History”, Heinemann Educational Books (Nigeria) Plc. PP 280-301. Obaro Ikime (Eds.), “West Africa Chiefs”, Ibadan University Press, 1970-216 Obaro Ikime, “Indirect rule in the Northern Nigeria”, Tarikh vol. 3 No 3, PP 1-15 S.A. Akintoye, “Revolution and Power Politics in Yorubaland” 18401893, Longman, London 1971. PP 33-74. 42 CHAPTER THREE 3.1 NEW-SOCIO-POLITICAL STRUCTURE IN IBADAN Education, being of the social development experienced in Ibadan in the 19th century contributed a great deal to the political and economic development of the people of Ibadan. Muslims, Christians and Traditional were given educational opportunities in Ibadan. As a result of this, people became exposed to Western values and Western health care system. Not only that, people began to know and understand the importance of social amenities like electricity, pipeborne water which make life worth living for the people of Ibadan. The few people who were educated participated actively in political activities in the then Western region and Nigeria as a while. People like Late Bode Thomas, Late Chief Adegoke Adelabu and others let the people know and understand the position of Ibadan in the politics of Nigeria. These politicians used their education to foster political development of Ibadan and also to create political disturbances that engulfed Nigeria in the 20th century and which also 43 affected Ibadan. In 1962, there was political unrest in the Western region, there was serious assassination threats. Social development again influenced the economic activities of the people of Ibadan. They now traded far and near. As a result of this commercial activities led to rapid economic development in ibadan. Their articles of trade now include the adopted European materials such as shoes and clothes. Trading in locally made materials such as pottery, craftwork was also boosted. This inturn generated income for the traders of Ibadan. Moreover, Western education had great impact on the economy of Ibadan. Coca planting was encouraged as well as its trade. The religious aspect of social and political development is vivid. It was said that the new religions made valuable contribution to the social, political, economic and cultural lives of the people of Ibadan. Because the Christian missions were found in almost every sector of the society. They were in the forefront in the promotion of Western education, orthodox health services and in the agricultural sector. 44 Western education which is the bane of the social and political development in Ibadan is attributable to the advent of Christianity. The Christian missions introduced the Western education. The Islamic education and Christian education wanted to reduce Yoruba language to writing, but the Christians adopted the Roman alphabet which was later put into proper use. 3.2 IMPACT OF BRITISH INTERVENTION IN THE 19TH CENTURY WARFARE One of the political causes of the 19th century warfare was the collapse of the central authority and army of Oyo following the successful revolt of Afonja the Kakanfo in 1817. The consequent establishment of an independent state of Ilorin by him marked the beginning of the warfare in Yorubaland in the 19th century. As the strong controlling and uniting hand of the central authority was no more, Yorubaland was thrown into confusion and strife as the obas or provincial governor following the example of Afonja began to carve 45 out kingdoms for themselves and the traditional hostilities between the various towns were let loose. Importantly, the Fulani menace on Yorubaland was another important outbreak of the 19th century warfare. The Fulani pressure on the northern Yoruba states with the consequent conquest of old Oyo in 1837 generated a southward population movement which accentuated the civil wars as refugees fleeing south from the Fulani onslaught sought new settlements but were resisted by the resident inhabitants. The Fulani contributed to the civil wars not only by warring on the northern Yoruba states, but also by the skill with which they set one king against another in order to increase the area under their control. The state of civil strife in Yoruba land was aggravated by the struggle for supremacy among the provincial kings or obas to the south. They sized the opportunity of the confused situation to expand their states at the expenses of each other. The Owu war (1821-1825) is a typical example. The Ijebu allied with Ife to destroy owu town 46 whose inhabitants fled into Egba territory. Then the Ijebu in alliance with Ife and Oyo destroyed several Egba towns. It was refugees from these wars that funded Ibadan in 1829 and Abeokuta in 1830. these two towns soon developed into powerful city-states and joined in the struggle for supremacy. 3.3 ROLE OF IBADAN IN THE EXTENSION OF BRITISH INFLUENCE IN THE INTERIOR The long wars in the interior were no doubt affecting trade in Lagos adversely. In 1861, Lagos had become a British colony and the British Governor there depended on customs duties from trade to maintain the Lagos administration. If trade was to go on, then the British must intervene to stop the endless wars in Yorubaland as these wars were hampering the free flow of trade to and from the coast. So various attempts were made to extend British political influence to the hinterland in order to bring the wars to an end. The opportunity for British intervention came when the Egbado long oppressed by the Egba appealed to the British Governor to 47 place them under British protection. Thus in 1890, Governor Moloney established a small British garrison at Ilaro the capital of Egbado. This marked the beginning of British military occupation of Yoruba land. In 1892, a punitive expedition was sent against Ijebu. As Crowther put it, “The speedy defeat of the Ijebu was the most significant step in the British occupation of Yorubaland”. In 1893, Abeokuta entered into a treaty with the British Governor Gilbert Carter. She agreed to submit all disputes between the Egba and the British to the Governor’s arbitration allow free trade and abolish human sacrifice provided her independence was guaranteed. A similar treaty made with the Alafin of Oyo granted the British free access to all Yorubaland, promised free trade, the toleration of Christianity, abolition of human sacrifice, and not to enter into any treaties with other powers without the permission of the Governor of Lagos. Finally, in the same year (1893), Ibadan accepted a similar treaty after it had been assured that it would not compromise her 48 independence. However, this treaty made Ibadan the headquarters of Yorubaland. Following this, a British Resident and a small force were stationed in Ibadan. 3.4 THE STATUS OF IBADAN IN THE POLITICAL ORDER By 1840, Ibadan evolved into on essentially military state. Though, the almost university Yoruba chieftaincy system of two coders of chiefs (the civil and the military) had emerged at Ibadan, in practice, qualification for a chieftaincy title was usually decided by military prowess. Chieftaincy title was not hereditary. Any man, regardless of his place of origin of his birth, could become a chief, if he showed that requisite military capabilities and could rise by promotion to the leadership of Ibadan State. Many adventurous men from all over Yorubaland migrated to Ibadan to seek the military honours which they could not hope to advice in their own place of origin. In this regard, Akintoye in his book Revolution and Power Politics in Yorubaland 1840-1893 has noted that “Chieftaincy title in 49 Ibadan was not hereditary”, however, the assertion by Akintoye that “any man, regardless of his place of origin or his birth, could become a chief and could rise by promotion to the leadership of the Ibadan state”. This statement would however need more clarification. Even though Ibadan is an egalitarian society which was based on Republican constitution, the point still remains that not “any man” could assumed the political destiny of Ibadan. It is a tradition that whoever aspire to become the political chief in Ibadan and especially the Olubadan of Ibadan ought to be an Oyo Yoruba man. The first man to hold a title in Ibadan was Oluyedun. Immediately, the man took charge of Ibadan town after the defeat of Maye, the elders met and appointed oluyedun as their heads. And, he too conferred chieftaincy titles on important military men and distinguished civilians. Lakanle was made the Otun Kakanfo, Oluyole was made the Osi Kankafo while Bankole became Asipa. The Bale himself assumed his father’s title Are-Ona Kankafo. However, after the death of Oluyedun, Oluyole became the Basorun. The first 50 chieftaincy arrangement was made, his reign could also be associated with regular order of creating titles. Ibadan under Oluyole adopted an open door policy to all new comers whatever their antecedents. Ibadan political and administrative institutions could not in the circumstances of the early period in the 19th century but be a reflection of military society. Indeed, in no other Yoruba town was there such close interrelationship between the military and the political aspect of government. Thus, it could be said that Ibadan had a lot of advantages through this was unlike the other towns such as Abeokuta, where group of immigrants from various towns still maintained their separate identities under the separate leaders. After Oluyole, Ibadan drew and redrew its constitution, particularly as affecting chieftaincy institution. Offices were now created as the necessary for them arose. 51 REFERENCES A.B. Fafunwa: “History of Education in Nigeria”. Pp. 141-148. B.A. Awe: “The end of an experiment: The Collapse of the Ibadan Empire 1877-1893”, J.H.S.N. volume 3 No 2, December 1965 P. 221 E.A. Ayandele: The Missionary impact on Modern Nigeria 18421914. Western Printing Services Limited, Bristol, Great Britain, 1966. p. 298 – 343. J.A. Atanda: “ An Introduction to Yoruba History PP 41 – 43. K. Morgan: “Akinyele’s Outline History of Ibadan” Ibadan, Caxon Press. Pp 31. L. Richard Sklat: “ Nigerian Political Parties” Nok Publisher International, New York, 1963, pp 289 – 290. M. Crwther: “The Story of Nigeria” (London, Faber and Faber, 1962) pp. 157-159. Rev. Father Oguntuyi: Aduloju Dodondawa”, 2nd Edition (Ibadan, 1957) pp. 40 – 42. Samuel Johnson: “The History of Yoruba from the earliest times. (Lagos, C.S.S. Book Shop, 1973) pp. 321 – 329. W. Ojo: “Folk History from Imesi-Ile, Nigeria 1953. pp 40 – 42. 52 CHAPTER FOUR 4.1 REFLECTIONS ON THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF IBADAN INDIGENES The central council of Ibadan Indigenes (CCII) was founded in June 1982, by the Ibadan Progressive Union (IPU), Lagelu “16” club and the Ibadan Descendant Union (IDU) University of Ibadan / The Polytechnic, Ibadan. These three indigenous socio-cultural organizations were convinced that Ibadanland was blessed with abundant human and material resources. Indeed, they believed that all indigenes should pool these resources for the sustained growth of the frontline city in black Africa. There was also the deep seated conviction that such an umbrella organization would advance the interest of the people of Ibadanland. Today, the council is the umbrella body of all clubs, societies, union and Associations of Ibadan stock in various sphere of life worldwide with over 140 constitution clubs in Nigeria, United Kingdom, United States of America, Saudi Arabia etc. His Royal 53 Majesty, the Olubadan of Ibadanland is its Grand patron. CCII’s first president was late chief S.I. Amade, the former Treasurer of Ibadan Native Authority that later metamorphosed into Ibadan phunicipal Government. A member of the Ibadan Progressive Union (IPU) he was the president from 1982 to 1989. Late Chief Oseni Oyetunji Bello, one of the most respect cooperative Administrators in Nigeria, succeeded him in 1989. He served the council with dignity irrepressible charm and dedication. The next National President indicted in 1996 was Chief Jacob Olabode Amoo, OON, a distinguished industrialist and philanthropist par excellence. The current National President is Chief Yusuf Akande Akano, a distinguished legal practitioner. All these men have used their robust intelligence, strategic thinking and resourcefulness to improve the fortune of CCII. The central council of Ibadan indigenes has also benefited from the caliber of men who have held its secretariat; special mention must be made of Dr. T. Adejare Fadare who guided the affairs of the 54 councils secretariat for eight years during pioneering days. He was succeed as the Secretary General by Alhaji B.A.O. Ladeji, who also served CCII with exemplary dedication. His successor in office was Dr. Niyi Adelakun, in 1997. On his appointment as the commissioner for education Oyo State in 1999, Mogaji Gbade Ishola became the acting Secretary General between 1999 and 2001, at the critical stage of caretaker arrangement, Chief bayo Oyero, a seasoned technocrat served as the secretary General between October 2001 and May 2003. from 2nd May 2002, Mr. Olatunji Muhammad Oladejo, a young, dynamic and prodigious University Administrator became the Acting National Secretary. Again, Mogaji Gbade Ishola took over as the National Secretary from May 6, to May 2005. Really, all these worthy Ibadan men have served the central council of Ibadan Indigenes\ with great commitment and brought dignity to the council’s various periodic and annual activities. In periods of crisis, the council has profited immensely from their maze of experience. In 1998, the foundation laying ceremony of the Ibadan 55 House was performed. The complex which is the secretariat of the central council of Ibadan Indigenes is the first socio-cultural organization multipurpose building in Nigeria. The complex which sits on 5.233 hectares at the foot of Agala hill, Oke Aremo Ibadan has been commissioned by then Kabiyesi His Royal Majesty Late Oba Y.B. Ogundipe CFR Arapasowu 1 on Saturday 26th May, 2007. it comprises a main hall for about 500 people reserved mainly for activities such as conferences / meetings, board-rooms, symposia, social engagement etc. Also, it contains the office block for various administrative operations of the central council of Ibadan Indigenes. The council organization various activities throughout the year round to improve the quality of life of the people of Ibadanland. One of these activities is the Annual Ibadan week celebration that was first held in 1992, with the overall aim of uniting all indigenes for self help. The council keeps growing like an oak tree everyday. 56 4.2 IMPACT OF PROVISION OF BASIC AMENITIES The first University to be set up in Nigeria was the University of Ibadan. Established as a college of an autonomous University in 1962. It has the distinction of being one of the premier educational institutions in Africa. The polytechnic Ibadan is also located in the city. There are also numerous public and private primary and secondary schools located in the city. Other noteworthy institutions in the city include the University of Ibadan Teaching Hospital also known as University College Hospital (UCH) which is the first teaching hospital International in Institute Nigeria; of the Tropical internationally Agriculture acclaimed (IITA); Nigerian Institution of Social and Economic Research (NISER). Also cocoa Research Institution of Nigeria, the National Horticultural Research Institute (NIHORT), all under the auspices of Agricultural Research Council of Nigeria; the Forestry Research Institute of Nigeria. Ibadan has an airport, Ibadan Airport, and was served by the Ibadan Railway Station on the main railway line from Lagos to Kano. 57 (No longer operating). The bad economic situation in the country has adversely affected the quality of public transportation. The city is respectively well linked by road, rail and air both domestic and internationally. The intra city road network provide the major links with its different parts. Recently, the Ibadan – Lagos expressway, the Ring road network were built to ease traffic congestion in the city. Also, Ibadan has many recreational centres and tourist centres of attraction: Liberty stadium the first stadium in Africa and Lekan Salami stadium, the polo club, the botanical Garden, the Zoological Garden and The Trans Wonderland Amusement Park. The cultural centre, Mapo Hall, Ido, cenotaph and Bowers Tower are other tourist centres of historical value. Another prominent landmark, cocoa House, was the first skyscraper in Africa. It is one of the few skyscrapers in the city and is at the hub of Ibadan commercial centre. There is also a museum in the building of the Institute of African Studies, which exhibits several remarkable pre-historic bronze 58 carvings and statues. The city has several well stocked libraries and is home to the first television station in Africa. 4.3 THE ECONOMIC ORDER IN IBADAN With its strategic location on the non-operational railway line connecting Lagos to Kano, the city is a major centre for trade in cassava, cocoa, cotton, timber, rubber, and palm oil. The main industries in the area include the processing of agricultural products; Tobacco processing and cigarette (manufacture); flour milling, leather – working and furniture-making. There is abundance of clay, kaolin and aquamarine in its environs, and there are several cattle ranches, a dairy farm as well as a commercial abattoir in Ibadan. Dugbe market is the nerve center of Ibadan’s transport and trading network. The haphazard layout of the city’s rods and streets contribute largely to the disorderly traffic and make it very difficult to locate and reach destinations. The best method to move about the city is to use reference points and notable land markets. 59 Ibadan has a few other important industries establishment like the confectionaries, oil processing plants, soft drinks, bottling and food factories, feed mills, tobacco factory and flour mills. Other are sawmills, paper mills, foam products, concrete poles and block making, chemicals, paints and petroleum oil deport. The government tries to promote industrial establishment by creating industrial estates, with a basic infrastructure, such as Owode Olubadan, Oluyole and Lagelu Industrial Estates. Its, however, upon the commercial sector that the city’s development mainly depends. As of 1991, close to 50% of its economically active population were commercial workers, Oja’ba, Ayeye and Oranyan arr the Traditional markets. While Gbagi, Agbeni, Bodija, Alesinloye and Gate are modern ones. They trade foodstuff, textile goods, locally woven strips of cloth or “Aso Oke”, household utensils, electronics and pharmaceuticals. The production and related workers are next in importance, with 265 of the working population. They are followed by professional / 60 technical and related workers (10.9%). Other occupations the people are engaged in are as administrative and (4.5%) and clerical and related workers (2.6%). The agriculture and related workers features last with 1.9%. 4.4 IMPACTS OF POLITICS ON IBADAN In nineteenth – century, the military elite ascribed an ‘elderly’ status to itself as the protector of the community. This was institutionalized through an elaborate patronage system of babaogun (war patron) whereby a distinguished military chief became a leader and ‘father’ of hundreds of people who were his followers and who gave him their allegiance. Falola (1984:194) further describes the system thus: It was Compulsory for everybody to have a babaogun, who must be obeyed. The People must give part of their product to babaogun, and must follow him to war when called upon to do so. They also constitute his labour force 61 when he wanted to build or repair his compound, clear, construct roads or do any important task. In this way, the entire population was placed under the protective custody of the military chiefs, who defended them against external aggression and represented their interest in the town council. This patronage system was so entrenched in Ibadan by the middle of the ninetieth century that, when the Rev. David Hinderer and his missionary party arrived in 1953, they were immediately placed under a babaogun. Throughout the nineteenth century, the Ibadan military political structure continued to evolve, as successive military leaders frequently modified it. It was not until the twentieth century that it eventually attained some degree of stability. One notable feature of this political structure as from the mid nineteenth century was the distinction between the civil and military chieftaincy lines. This civil line, locally known as the Egbe Agba (company of elders), was headed by the Baale, and was 62 charged with day-to-day administration of the town. The Baale was usually a war veteran, but sometimes, the chief under him were still active warriors. Again, the fluidity in the system could also be seen in the fact that succession to the Baleship for a long time was not from the Baale line but from the Balogun (military) line (Morgan, (Part 1). n.d.: 105). It was only in the twentieth century that the idea of alternate succession became a fixed principle because the absence of wars had now made the Baleship attractive to (and has infact become the ultimate goal of) all the chiefs in the two principle lines. In the final analysis, Ibadan polities could be described as a complex and intricate web of diverse elements. To isolate the ideology of age as the only defining feature of political relationships would amount to an oversimplification of the issues at play. Samuel Johnson (1921), I.B. Akinyele (1981) and Kemi Morgan (part 1, n.d), present in their respective works similar accounts of competition, strife, intrigues and crisis in Ibadan politics, which were base not just on generational or horizontal cleavages but also on vertical rivalries 63 among ‘peers; on gender-related issues and other forms of political maneuverings. 4.5 CONCLUSION Undoubtedly, the changing role of the traditional political institution in Ibadan in the twentieth century have been great. From the position of a Baale, who was a primus inter pares (first among equals) with other chiefs in the council. By 1936, the status of Baale of Ibadan had been changed to Olubadan (king of Ibadan), an Oba of great status. Military ability used to be the principal qualification for chieftaincy posts in the pre-colonial period. By 1934, some of the educated elites in Ibadan had been made chiefs, and chieftaincy system had expanded to include the educated elites as councilors who with their youthful vigour were able to influence the council to devote itself to progressive ideals for the development of the city. Nevertheless, the important thing that should be noted about Ibadan is that despite all the changes brought upon its traditional political institution in the twentieth century, the traditional political 64 institution of Ibadan were still preserved. Despite all these changes in the traditional political institution of Ibadan, the Bale institution still remained, though by 1936 his title was changed and likewise his status. Although, the Bale had become an Oba, with the same status with many of his counterparts in Yorubaland, yet unlike many other Yoruba town where the Obaship institution is hereditary, the post of the Olubada of Ibadan is not hereditary even till date. The system of promotion within the ranks still exist in Ibadan and the person who becomes an Olubadan, would have started off from the rank of a Mogaji, and gradually he would be promoted until he reaches the top post of the land. This resulted in the reason why most of the ruling Olubadan of Ibadan are usually fairly old men. Finally, the traditional political institution in Ibadan, despite all the change brought into it, it still remain very important in the traditional political institution and administration of the town. Instead of loosing its value, the chieftaincy institution is becoming more appreciated, even among the educated elites of the city. 65 REFERENCES Adeboye, O.A. 2007. The Changing Conception of Elderhood in Ibadan, 1830 – 2000, Nordic Journal of African Studies 16 (2): PP 216 – 278. Areola, O. The special Growth of Ibadan City and its Impact on the rural Hinterland, in M.O. Filani, F.O Akintola and C.O Ikporukpo edited Ibadan Region, Rex Charles Publication, Ibadan, 1994. page 99. Folala, T. 1984: The Political Economy of a Pre-Colonial African State Ibadan, 1830 – 1900. Ife University of Ife Press. Foner, N. 1984: Ages in Conflict: A Cross – Cultural Prespective on Inequality Between Old and Yound. New York: Columbia University Press. G.O. Ogunremi (ed), Ibadan: A Historical, Cultural and SocioEconomic study of an African City. Lagos: Modelor Press. 66 Gohen, M. 1988: Land Accumulation and Local Control: The Negotiation of Symbols and Power in NSO, Cameroon. In:R. Downs, and S. Reyna (eds), Land and Society in Africa. Durham: University of New England and Press. Lyold, P.C. et. al (1967). The City of Ibadan. Cambridge University Press. Ogunbiyi, I.A. and Recommit, S. 1997. Arabic Papers from the Olubadan Chancery I:A Rebellion of the Ibadan Chieftaincy OR, At the Origins of Yoruba Arabic Prose. Sudanic Africa, 8, 109 – 135. Olufemi Vaughan. Nigerian Chiefs: Traditional Power in Modern Politics, 18900s – 1990s. Van Rouveroy Van Nieuwaal, E.A.B. and Dijk, Rijk Van (eds) 1999. African Chieftaincy in a New Socio-Poliyical Landscape. Hamburg: LIT Verlag. Vaughan, O. (ed) 2005. Traditional and politics: Indigenous Political Structures in Africa. Trenton, New Jersey: African World Press. Watson, R. 2003. ‘Civil Disorder is the Disease of Ibadan’: Chieftaincy and Civil Culture in a Yoruba City. Oxford: James Currey. 67