Living With History Syllabus

Living With History:

History, Culture and Contemporary Life in England

WHEN: May 18 – June 9, 2016 (Confirmed)

WHERE: London & Exeter, England

CREDIT HOURS: 4

INSTRUCTOR: Dr. Linnea Goodwin Burwood, Professor of History, State University of New York

CONTACT: burwoolg@delhi.edu

PLEASE NOTE: THE SYLLABUS IS INDICATIVE. IT IS COMPLETE IN TERMS OF THE STRUCTURE OF THE

COURSE AND IN ITS ESSENTIAL DETAILS. DATES FOR GUEST SPEAKERS IN PARTICULAR ARE NOT FINAL

AND ARE SUBJECT TO CONFIRMATION. A FINAL SYLLABUS WILL BE POSTED AND SENT TO YOU

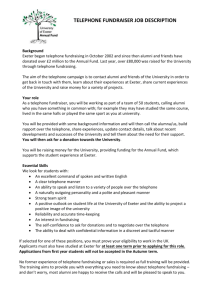

COURSE DESCRIPTION:

This 3-week course, taking place in London and Exeter, is an attempt at “Applied History.” We look at the history of England through these two cities. We try to get into the heads of people in the past by reading a well-researched historical novel by Michael Jecks. We look at the physical remains of the place in which the novel is set. We meet and talk with the author. We meet and talk with people whose jobs are hundreds of years old—a serving Member of Parliament, the Lord Mayor, the Dean of the cathedral.

We meet and talk with people working today who have to negotiate the past, from a representative of the Chamber of Commerce to a construction developer. And we meet and talk with regular people. How does the past impact the way they live today and the ways in which they make sense of the world?

We will tour Westminster Abbey, see the changing of the guard at Buckingham Palace, the National

Gallery, Trafalgar Square, the City of London, the oldest continuously used public building in England, an original copy of the Domesday Book (1086), and much more.

PRE-REQUISITES: None

STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES:

These outcomes specifically address SLO5 of the New York State General Education requirements—see if the content of this course meets a general education requirement in your own degree program if you are

outside New York State.

1-knowledge of the development of the distinctive features of the history, institutions, economy, society and culture of Western Civilization; and

2-relate the development of Western civilization to that of other regions of the world

COURSE OBJECTIVES:

1) Knowledge of the basic narrative of English history: political, economic, social and cultural

2) Skills required to succeed in a history course: the ability to write a formal essay, marshal and evaluate evidence and think critically

3) Skills required to connect the present with the past: the ability to formulate survey questions, conduct fieldwork and interpret survey results in a cross-cultural perspective.

MEASUREMENT CRITERIA:

STANDARDS

Basic narrative of English

History

Understanding Contemporary

Relationship With the Past

Exceeding

Meeting

The student demonstrates a well-rounded understanding of the narrative of English history.

Mechanics of grammar and critical thinking are applied

The student demonstrates a major understanding of the connections of contemporary

English people with their past.

Mechanics of grammar and critical thinking are applied.

The student demonstrates an adequate, although incomplete, understanding of the narrative of English history.

Substantive grammar and some critical thinking applied

The student demonstrates an adequate, although incomplete, understanding of the connections of contemporary English people with their past. Substantive

grammar and some critical thinking applied.

Approaching

Not Meeting

The student demonstrates some understanding of narrative of English history.

Lacks grammar skills and small evidence of critical thinking

The student demonstrates some understanding of the connections of contemporary

English people with their past.

Lacks grammar skills and small evidence of critical thinking.

The student has little to no ability to demonstrate an understanding of the narrative of English history. Lacks fundamental grammar and critical thinking skills.

The student has little to no ability to demonstrate understanding of the connections of contemporary

English people with their past.

Lacks fundamental grammar and critical thinking skills.

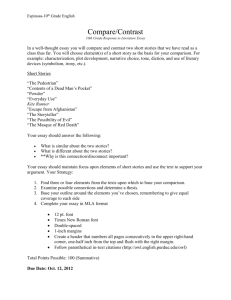

COURSE ASSESSMENTS:

The course grading is out of 100 points. No late work will be accepted.

1) One essay on British History (drawn from posted readings and web links). 400 – 500 words. Worth 10 points. Due May 18th on the plane (Paper copy!)

2) Daily Diary Entries based on format to be distributed. Worth 35 points. We will meet at the end of each day to debrief and aid you with the diary entries. The diaries will be collected on May 29 (15 points) and June 6 (15 points) for grading purposes.

What to include:

1-paragraph on what you saw and did & your reactions

1- paragraph on your reading in the Michael Jecks book [you need to read at least 40 pages per day before you meet the author and discuss his work—and write the essay]

The Professor will ask questions so you have a great idea what to write.

Final Diary collection on June 11 on the plane (5 points)

3) Essay on Medieval Exeter (drawn from the Jecks book and other Exeter sources). 5 - 7 pages. Due June

4.Worth 25 points

4) Red Coat evaluation. Format to be determined. Due June 8. Worth 10 points.

5) Final Essay on contemporary connections of the English with their past. 5 pages. Due June 30. Worth

20 points.

All assignments submitted in England should be hand-written or hand-printed—legibly, please!

CLASS SCHEDULE OF TOPICS OR OUTLINE:

The finalized course schedule will be subject to confirmation of all arrangements. This is the anticipated schedule. Some dates and arrangements may change. All reading assignments must be completed before the session for which they are indicated.

Wednesday, May 18. Overnight group flight Philadelphia to Exeter via Dublin.

First Essay due. (10 points)

Essay Question: England has a rich and diverse history. After reading the posted materials and web links, explain what you think are the most interesting and your observations on what you hope to learn during this course.

English History. Worth 10 points. 400 – 500 words.

Reading for Essay:

Posted web links:

“British History in Under Five Minutes”—2 page essay on the program webpage.

Museum of London – London History http://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/london-wall/whats-on/galleries/

Royal Albert Memorial Museum Exeter http://www.rammtimetrail.org.uk/

Begin daily reading Michael Jecks, City of Fiends!(if you haven’t started it already)

Thursday, May 19. Arrive in Exeter.

On-site orientation.

Guided walking tour of city center by instructor.

Begin Daily diary entries after debrief

Friday, May 20. Session 1 on English History. Return of first essay.

Debrief & discussion.

Saturday, May 21.

Sunday, May 22.

Monday, May 23. Session 2 on English History & History of Exeter.

Hand in Daily Diary Entries for comment and feed-back.

Daily debrief and discussion

Tuesday, May 24. 9:00 Set up for Red Coat Guides meetings. Set up for Lord Mayor.

10:30 Meet with Lord Mayor of Exeter and immediate past-Lord Mayor of Exeter. Guided tour of

Exeter Guildhall—the oldest continuously used public building in England

2:00 Group tour of medieval Exeter.

4:30 Red Coat Guides meeting

Daily debrief & discussion

Wednesday, May 25. Session 3 on English History/History of Exeter.

9:00. Set up for Dean of the Cathedral.

10:00. Guest: Dean of the Chapter of Exeter Cathedral. What does he do? How do you run an ancient institution on modern lines? How do you keep it all going? Challenges and opportunities.

Followed by: guided tour of the Cathedral and medieval roof.

Daily debrief and discussion.

Individual red coat tour (evening)

Note: You will need to go on at least two red coat tours while in Exeter in addition to the group tour, so you can write about them. A list of times and subjects are here: http://www.exeter.gov.uk/index.aspx?articleid=2851

Thursday, May 26. Session 4 on City of Fiends

Reading: Michael Jecks, City of Fiends. By now you should have read the first 300 pages!

10:00 Visit to Exeter Cathedral Library—Exon Domesday Book, Exeter Book, illustrated medieval manuscripts, ancient medical texts…

Red coat tour

3:30 Visit to Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter. Local History & Archaeology presentations.

Daily Debrief & Discussion

Friday, May 27 Session 5. Making a Living in Exeter from the Middle Ages to the Present

Canal Walk to Double Locks.

Daily Debrief & Discussion

First collection of diaries 15 points

Saturday, May 28. Free Day. Optional. Dartmoor & Widecombe-in-the-Moor (additional cost)

Sunday, May 29. Free Day.

Monday, May 30. Session 6 on English History/History of Exeter: The significance of World War Two.

Red coat tour/street surveys

Daily Debrief & Discussion

Tuesday, May 31. Session 7 on English History/History of Exeter, 1945-1970

Guests: XXXX, Manager, Wetherspoon’s.

Red coat tour

Daily Debrief & Discussion

Wednesday, June 1. 9:00 Set up for Mike Jecks.

3:00 Guest: Michael Jecks, author of City of Fiends. Why does he write about historical fiction?

Why does he do so much research? Why historical crime fiction? Why Exeter and the county of

Devon in particular?

Daily Debrief & Discussion

Thursday, June 2. Session 7 on English History/History of Exeter, 1970 to the present

Meeting with Alex Richards, reporter for the Exeter Express & Echo newspaper. The E&E wants to do a story about us and our visit!

500 word Essay on Michael Jecks, City of Fiends due. Questions will be supplied before the

Jecks meeting 25 points

Friday, June 3 (Tentative) Living in Exeter—meet the family—lunch or traditional cup of tea and scones.

Second collection of diaries 15 points

Daily Debrief & Discussion

Saturday, June 4. Exeter to London.

River Thames walk—hostel to Westminster Bridge, past the Houses of Parliament, Big Ben and Westminster Abbey to Lambeth Bridge and back to the hostel.

Sunday, June 5.

Visits: London Underground, Westminster to Temple to see Knights Templar church and law courts. Walking tour of City of London. Museum of London, St. Paul’s Cathedral, Tower Bridge, the Gherkin & the Shard.

Monday, June 6.

Red Coat Piece due: 10 points

Readings: Assigned Readings.

Guest: Ben Bradshaw, MP for Exeter.

Followed by a tour of the Houses of Parliament

Tuesday, June 7. London in British History.

Daily Debrief & Discussion

Wednesday, June 8. London Today—world capital, anomaly in Britain. Old & new.

Visits: Westminster Abbey (inside), Harrod’s, Kensington Gardens

Daily Debrief & Discussion

Farewell Dinner.

Thursday, June 9. Return to the United States.

Final Daily Diary Entries due on the plane. 5 points

Tuesday, June 30. Last Day to Submit 5-7 page Essay on Contemporary Connections (20 points)

Required Materials

Pens

A notebook for the diary entries

Paper for handwritten essays

Michael Jecks, City of Fiends London: Headline Book Publishing, 2005. ISBN: 978-1471111815

ACADEMIC HONESTY:

What is Plagiarism?

Plagiarism is the taking of someone else’s ideas and writing them as if they are your own. This may take the form of using, word for word, the writing of someone else in your own essay or it may be using their ideas as if they are your own. Even if you take someone else’s writing and change a word or two here and there, or a phrase, or re-arrange a couple of sentences, it is still plagiarism. The point is, these are not your ideas and you have not indicated whose they actually are or where you found them. You should use footnotes (or endnotes) to indicate the source of any material you have found in someone else’s writing that is not commonly known. If you find a phrase, sentence, or two that is written in such a way that you could not say it so well yourself and you think it is important to have in your essay, place the material in quotation marks to show they are someone else’s words and then footnote the source.

It is often also a good idea to preface ideas you have found somewhere with a phrase like “according to historian John Doe,…” This has the effect of not only demonstrating your academic honesty but also gives greater credence to your work since it is not only you who thinks this way.

Sometimes people are not aware that what is described above is a serious offense in academic writing.

Now you are warned! If you have any doubts at all, ask your instructor!

There are other forms of plagiarism that are quite obviously offenses to even the least aware. Getting someone else to write your assignment, or to finish it off for you, using a paper written for the same course last year or longer ago, or purchasing a paper online are so obviously serious forms of cheating/plagiarism that when detected (you would be surprised at how easy it is to detect!), the punishment is even more severe.

STUDENT CONDUCT IN THE CLASSROOM: The instructor in the classroom and in conference will encourage free discussion, inquiry and expression. Student performance will be evaluated wholly on an academic basis, not on opinions or political ideas unrelated to academic standards. However, in instances where a student does not comply with the Code of Student Behavior or with an instructor's reasonable conduct expectations in the classroom, such non-compliance can affect the student's evaluation and be cause for permanent removal from class or dismissal from the program and subsequent academic disciplinary processes at

the home campus. If students are dismissed from the program they are responsible for any additional expenses in getting themselves home.

STUDENT CONDUCT OUTSIDE THE CLASSROOM. Students in the program are subject not only to the rules of reasonable student conduct and the Student Code of Conduct of their home university or college, they are also subject to the laws of the United Kingdom while they are in-country. As in the

United States, ignorance is no defense if laws are broken.

CELL PHONES/TAPE RECORDERS/ELECTRONIC DEVICES IN THE CLASSROOM: Students are required to turn off cell phones in class and may not use recording devices, unless the student has a documented disability which permits recording, or permission of the course instructor. A student's refusal to turn off a cell phone will be cause for dismissal from class. In addition, the use of ANY electronic device which disrupts class will also be cause for dismissal from class.

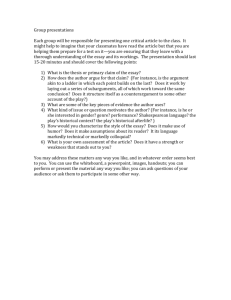

Writing an Essay for a History Class

The rules for writing a History essay are similar but not the same as for other subjects. Remember, what makes History different from other subjects is that it is all about time and the effects of the

passage of time. You can only do well on History essays if you make sure you show the effects of the passage of time.

The main difference between writing for history at college and writing in high school is that in college you will be asked to answer a specific question. For example, you may have written an essay in high school on the New Deal. In that essay, no doubt well written and full of facts, you will have told a story, much like you might find in a newspaper telling what happened. In college we want you to question

WHY things happened the way that they did, what were the CONSEQUENCES, and to try to determine what factors were more important and what were less important in your INTERPRETATION of what happened. Such an approach can be seen in the wording of the questions we ask you to write on. Using the New Deal example again, in college you will be asked to answer a question like “Did the New Deal have great impact on American History in the twentieth century?

All essays, no matter what the subject, have the same basic structure:

1. Introduction- A good introduction should not only grab the reader’s attention but should give an idea of the scope and limits of the essay. Here you need to reference the question directly, if nothing else it shows you have understood and its dimensions.

2. Middle- The middle carries the main burden of the essay. In history this is where you supply the argument and evidence to back up the argument. This is where you do not simply list what the components of the New Deal were but instead assess what programs really did help Americans get out of the Great Depression and if there were other factors (like President Franklin Roosevelt’s personality and political skill) that also had an impact and what that impact was. This is where you need to make decisions about how you will answer the question and try to make an argument that continues throughout the essay. So, if you have decided that the New Deal accomplished very little, this is where

you cite and analyze the evidence that led you to that conclusion. A good essay does not, of course, list all the things that support you argument and ignore all those inconvenient things that might suggest the answer is not so straightforward. You need to demonstrate you know about the awkward factors and have some sort of answer. (Hint: Hardly anything is cut and dried. All judgments are made by weighing the evidence. Some of it does not easily fit. Most judgments are made on the balance of evidence, not because absolutely everything points to an inescapable conclusion. Historians do not all agree or make the same argument about any given question.)

3. Conclusion- It is of necessity the shortest part of the essay, a paragraph or two. This is not the place to introduce new facts or arguments. All of that should be done in the middle section of the paper. The conclusion states your overall judgment of the paper based on the information that you have presented.

For example: “The New Deal was a noble experiment. Americans felt that the government was working hard in their interests to get them out of the Great Depression and back to work but in the end it solved very little. It took the natural recovery of the markets and the outbreak of World War II to solve the problems that the country had faced since 1929 with the stock market crash.”

Do’s and Don’ts

1. Make sure that your work is well presented (legible handwriting or printing, no coffee rings or crinkled paper).

2. Double space; use 1” margins and number your pages.

3. Use the spell checker on your computer! There is nothing worse to read than a paper loaded with fixable typing errors. That is why we tell you to proof read.

4. Always be specific and time period conscious. Show that you are in charge of the material. Never use vague words guaranteed to drive historians nuts like: soon, eventually, long age, once, if you look back, I will explain (why write this- your essay is for the explanation).

5. Write in formal English. It is not a conversation at Mac Hall. Being “chatty” and using slang is not going to help your grade.

6. Make sure that your writing is consistent: Make verbs agree with subject, ex. The Germans were not the Germans was.

7. Always write in the same verb tense. For history the simple past tense is best.

8. You must use footnotes or endnotes for quotes, non-common knowledge (For example did you know that in 1492 that the Spanish government expelled Jews and Muslims from Spain and that it was the height of the Spanish Inquisition?) and statistics (Numbers can be interpreted many different ways to fit a preconceived paradigm and must have a source given). Footnotes demonstrate to the reader

where the knowledge came from.

No parenthetical references in a history paper.

9. Here is the proper format for footnotes:

In the first usage of the source:

Michael Pollan, The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals (New York: Penguin, 2006),

99–100.

If you are using the same source for other footnotes:

Pollan, Omnivore’s Dilemma, 3.