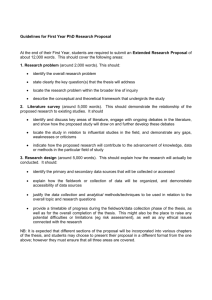

Essay Organization and Structure

advertisement

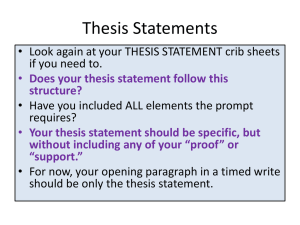

Essay Organization An essay has three main parts 1. Introduction: Hook, state the problem/question, state the thesis (thesis should answer your historical question) 2. Body: Topic Sentence: each paragraph should start with an analytical topic sentence (should answer a how/why question). Each topic sentence is a minor thesis that supports the main thesis. Evidence: Provide examples from the sources that support your minor thesis. Analysis: What does the evidence tell you? 3. Conclusion: A conclusion should re-state the thesis, but your conclusion needs to go beyond simply regurgitating your main points. Re-state the thesis in a concise manner and then explain why the problem is important. This is your time to place your problem in a larger framework. Introduction (see intro handout): Introduce the problem. Define terms Provide a road map to structure the paper State the thesis clearly Your introduction should be a paragraph and no more than two in a longer paper, so it is important to define your topic quickly. Be precise rather than vague and get to the point immediately. When and where are you in time? What are you discussing? If you are discussing the life of Harriet Jacobs, it is overly vague to introduce the setting and topic by referring to “slavery days,” because slavery has existed throughout the world and throughout time. Harriet Jacobs was a slave in North Carolina in the antebellum period. Be specific. Hook: capture the attention of your reader using an example, quotation, or statistic. Make sure this hook matches your theme. It is a great idea to refer back to your hook later in the body and or conclusion. Explain the structure of your paper—briefly provide a road map. The most important part of your introduction is the thesis, which should come at the end of the paragraph. The thesis should state your argument in one sentence. The sentences leading up to the thesis should have introduced key concepts and ideas so that the thesis makes sense when the reader gets to it. Here are examples of a weak and strong introduction. (www.bowdoin.edu/writingguides/) Weak Introduction: “Since the beginning of time humans have owned one another in slavery. This brutal institution was carried to its fullest extent in the United States in the years between the American Revolution and the Civil War. Slaveholders treated their slaves as chattel, brutalizing them with the whip and the lash. The law never recognized the humanity of the slave, and similarly regarded him as property. Consequently, there was a big disparity between private and public rights of slaves.” This thesis introduces two terms, “private” and “public” rights, that are not mentioned earlier. What are these concepts and why are they important? The vague background does not help to explain the premises underlying the argument. Furthermore, the thesis itself is weak because it does not answer a how, why, or so what question. More Effective: “To many supporters of slavery, the nature of slave rights had a dual character. On the one hand, in order to maintain the total dominance of the white master class, the law denied any rights to slaves. Publicly, the slave was merely property, and not human at all. Yet the personal records of many planters suggest that slaves often proved able to demand customary “rights” from their masters. In the privacy of the master-slave relationship, slaves did have rights that the master was bound to respect, on pain of losing his labor or subjecting himself to violence. This conflict between slaves’ lack of “public” rights and masters’ “private” acknowledgement of slaves’ rights undermined planter hegemony and permitted slaves to exert a degree of autonomy within an oppressive institution.” This paragraph does a much better job of introducing the problem and the concepts central to the thesis. All of the elements of the thesis are discussed in the preceding paragraph and yet the thesis does not simply restate the paragraph. This introduction also alerts the reader to the sources that will be used. The reader has a much stronger sense of how the argument and paper will be structured and what the author needs to do to prove the thesis. Body: this comprises the majority of your paper. This is where you will argue, analyze sources, and prove your thesis. How can you support your thesis? If you cannot easily answer this question, you may need to develop a stronger thesis. Your thesis can help you structure your paper. Think back to the thesis on our thesis practice sheet. “In his autobiographical Narrative, Frederick Douglass drew on techniques used in popular texts of his day—sentimental literature, the Bible, and rip-roaring oratory—to persuade his audience to reject slavery as a moral and political evil.” This thesis indicates an organization. You will need to divide the paper into sections on sentimental literature, biblical arguments, and oratorical techniques. Paragraphs: each paragraph should have the following structure. (see topic sentence/paragraph handout). 1. Topic Sentence Each Paragraph should start with an analytical topic sentence (minor thesis). Avoid descriptive topic sentences. Ask yourself if your topic sentence answers a “how” or “why” question. The remainder of the paragraph will support this minor thesis. 2. Evidence Provide support for your thesis that you paraphrase and quote from the sources. 3. Analysis Interpret and analyze that evidence. It is a good idea to end your paragraph with a sentence of summary analysis. 4. Transition. Your summary analysis can serve as your transition (see handout on transitions). Counter-arguments: History papers make their arguments with evidence and reason. One excellent way to prove your point is to predict and address counter-arguments. Ask yourself what counterarguments could be raised to cast doubt on your thesis. You can prove potential counter-arguments untrue. “While the WPA slave narratives seem to indicate that some former slaves recalled slavery with nostalgia, these sources must be used with care. In the Jim Crow South, African-Americans responding to white interviewers often gave calculated answers as a matter of personal safety.” Or, you can accept certain statements or facts but discuss context and explain how they do not, indeed, damage your argument. “While it is true that…” You cannot simply include evidence that supports your thesis and ignore other evidence. This will undermine your essay. Conclusion: This should be one paragraph long. It should briefly and clearly restate the thesis in the first sentence. The conclusion should also go beyond restating the argument. It should also address why the argument is significant, place the argument in a larger context, and raise larger questions.