Street Address - The Impact of School Start Times on Adolescent

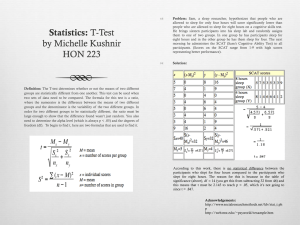

advertisement

Your Name Street Address City, State/Zip Phone, fax, and/or email Today’s date Addressee Street Address City, State/Zip Dear Superintendent Last Name and Members of the School Board, I am the parent/guardian of a student presently attending School Name. I am writing to request that the School District implement healthy start times for middle and/or high school students. To safeguard the welfare and intellectual potential of these children, sleep experts recommend a delay in morning classes until 8:30 a.m., or later. (Start time recommendations available infra; see also, Vedaa, Saxvig, Wilhelmsen-Langeland, Bjorvatn, & Pallesen, School start time, sleepiness and functioning in Norwegian adolescents (Feb. 2012) Scandinavian J. Educational Research, pp. 55-67 [10th graders get 66 minutes more sleep and performance on attention/vigilance tasks improves with one hour start time delay to 9:30 a.m.].) First period at High School commences time period before the earliest start time recommended by any expert. (See, e.g., O’Malley & O’Malley, School Start Time and Its Impact on Learning and Behavior, publish. in, Sleep and Psychiatric Disorders in Children and Adolescents (Ivanenko edit., Informa Healthcare 2008) pp. 83, 84, 89.) Middle School begins time period too early. (See, e.g., Lufi, Tzischinsky, & Hadar, Delaying School Starting Time by One Hour: Some Effects on Attention Levels in Adolescents (Apr. 2011) 7 J. Clinical Sleep Med. 2, pp. 137-143.) “[O]n school days adolescents are obtaining less sleep then they are thought to need, and the factor with the biggest impact is school start times. If sleep loss is associated with impaired learning and health, then these data point to computer use, social activities and especially school start times as the most obvious intervention points.” (Knutson & Lauderdale, Sociodemographic and behavioral predictors of bed time and wake time among U.S. adolescents aged 15–17 years (Mar. 2009) 154 J. Pediatrics 3, p. 426.) “School schedules are forcing them to lose sleep and to perform academically when they are at their worst.” (Hansen, Janssen, Schiff, Zee, & Dubocovich, The Impact of School Daily Schedule on Adolescent Sleep (Jun. 2005) 115 Pediatrics 6, p. 1560, italics added.) “The earliest school start times are associated with annual reductions in student performance of roughly 0.1 standard deviations for disadvantaged students, equivalent to replacing an average teacher with a teacher at the sixteenth percentile in terms of effectiveness.” (Jacob & Rockoff, Organizing Schools to Improve Student Achievement: Start Times, Grade Configurations, and Teacher Assignments (Sept. 2011) Hamilton Project, Brookings Inst. p. 7.) Although the evidence in support of delaying start times as benefiting the health, welfare, and academic performance of adolescents is overwhelming and uncontroverted (Troxel, The high cost of sleepy teens (May 23, 2012) Pittsburgh PostGazette; Hagenauer, Perryman, Lee, & Carskadon, Adolescent Changes in the Homeostatic and Circadian Regulation of Sleep (2009) 31 Developmental Neuroscience 4, p. 282), school schedules are often determined by politics, budgets, and athletics, rather than the best interests of students. (See Wolfson & Carskadon, A Survey of Factors Influencing High School Start Times (Mar. 2005) 89 Nat. Assn. Secondary School Principals Bull. 642, pp. 47-66; Wahlstrom, The Prickly Politics of School Starting Times (Jan. 1999) 80 Phi Delta Kappan 5, pp. 344-347.) There is no sound reason, however, why any of these concerns should prevail over the well-being of children. First, any adverse political fallout stemming from a shift to later start times should be diminished by the burgeoning evidence supporting the change. (See Wahlstrom, School Start Times and Sleepy Teens (Jul. 2010) 164 Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Med. 7, pp. 676-677.) Second, a study published in March of 2011 establishes that careful planning permits later start times to co-exist with athletics and extracurricular activities. (Kirby, Maggi, & D’Angiulli, School Start Times and the Sleep-Wake Cycle of Adolescents: A Review and Critical Evaluation of Available Evidence (Mar. 2011) 40 Educational Researcher 2, pp. 56-61.) Third, recent studies anticipate financial gains for schools (and students) when morning classes are delayed, a significant fact in times of economic hardship. (Edwards, Do Schools Begin Too Early? (Summer 2012) 12 Education Next 3; Jacob & Rockoff, Organizing Schools to Improve Student Achievement: Start Times, Grade Configurations, and Teacher Assignments, supra, pp. 5-11; Carrell, Maghakian, & West, A’s from Zzzz’s? The Causal Effect of School Start Time on the Academic Performance of Adolescents (Aug. 2011) 3 Am. Economic J.: Economic Policy 3, pp. 62-81.) Fourth, finding ways to adjust start times is the “job of talented, smart school administrators.” (Taboh, American Teenagers Dangerously Sleep Deprived: Tired teens physically, mentally, emotionally compromised (Sept. 9, 2010) Voice of Am. News; see also, Riddile, Time Shift: Is your school jet-lagged? (Mar. 14, 2011) Nat. Assn. Secondary School Principals, The Principal Difference.) Consistent with previous studies, the 2011 National Sleep Foundation poll found only 14% of teenagers between the ages of 13 and 18 report getting the recommended number of hours of sleep (9 or more) on school nights. (2011 Sleep in America Poll: Communications Technology in the Bedroom (Mar. 2011) Nat. Sleep Foundation, p. 40; see also, 2011 Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data User’s Guide (Jun. 2012) Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, pp. 74, 86; Teens and Sleep Poll a Wake-Up Call, Pediatric Sleep Experts Say (Mar. 2006) Brown Univ.) “Sleep deprivation among adolescents appears to be, in some respects, the norm rather than the exception in contemporary society.” (Roberts, Roberts, & Duong, Sleepless in adolescence: Prospective data on sleep deprivation, health and functioning (2009) 32 J. Adolescence, p. 1055.) “The consequences of this sleep deprivation are severe, impacting adolescents’ physical and mental health, as well as daytime functioning.” (Lund, Reider, Whiting, & Prichard, Sleep Patterns and 2 Predictors of Disturbed Sleep in a Large Population of College Students (Feb. 2010) 46 J. Adolescent Health 2, p. 125.) In 2010, CDC scientists reported, “Delaying school start times is a demonstrated strategy to promote sufficient sleep among adolescents.” (Eaton, McKnight-Eily, Lowry, Croft, Presley-Cantrell, & Perry, Prevalence of Insufficient, Borderline, and Optimal Hours of Sleep Among High School Students – United States, 2007 (2010) 46 J. Adolescent Health, p. 401.) Dr. Philip Fuller, Medical Director of the Mary Washington Hospital Sleep and Wake Disorders Center, explains: “Inherently, the majority of kids with a later start will get more sleep, which is beneficial to grades as well as being safer.” (Sklarew, Getting A’s with More Z’s: The fight for later school starts has backing from doctors and statistics (Nov. 2011) N. Va. Magazine.) “Students at later starting middle and high schools obtain more sleep due to later wake times and, in turn, function more effectively in school.” (Wolfson, Spaulding, Dandrow, & Baroni, Middle School Start Times: The Importance of a Good Night’s Sleep for Young Adolescents (Aug. 15, 2007) 5 Behavioral Sleep Medicine 3, p. 205.) “By recognizing the shift in biological rhythms during adolescence and delaying school start times accordingly, classroom experience can be matched to the times when adolescents are most alert and attentive.” (Coch, Fischer, & Dawson, Human Behavior, Learning, and the Developing Brain: Typical Development (Informa Healthcare 2010) pp. 382-383.) Economists from the University of California and the United States Air Force Academy note that since later start times have a “causal effect” upon improved academic performance in adolescents, delaying morning classes may save schools money. “A later start time of 50 minutes in our sample has the equivalent benefit as raising teacher quality by roughly one standard deviation. Hence, later start times may be a costeffective way to improve student outcomes for adolescents.” (Carrell, Maghakian, & West, A’s from Zzzz’s? The Causal Effect of School Start Time on the Academic Performance of Adolescents, supra, 3 Am. Economic J.: Economic Policy 3, p. 80.) The benefit is greatest for the bottom half of the distribution, suggesting that delaying start times may be particularly important for schools attempting to reach minimum competency requirements. (Edwards, Early to Rise? The Effect of Daily Start Times on Academic Performance (Dec. 2012) 31 Economics of Education Rev. 6, p. 978.) Brookings Institute economists “conservatively” estimate that shifting middle and high school start times, “from roughly 8 a.m. to 9 a.m.” would increase student achievement by 0.175 standard deviations on average, with effects for disadvantaged students roughly twice as large as advantaged students. (Jacob & Rockoff, Organizing Schools to Improve Student Achievement: Start Times, Grade Configurations, and Teacher Assignments, supra, Brookings Inst., pp. 10, 21, n. 7.) The economists estimate a corresponding increase in individual student future earnings of approximately $17,500, at little or no cost to schools; i.e., a 9 to 1 benefits to costs ratio when utilizing single-tier busing, the most expensive transportation method available. (Id., pp. 5-11.) 3 In addition, studies have shown young people between 16 and 29 years of age are “the most likely to be involved in crashes caused by the driver falling asleep.” (Millman, edit., Excessive Sleepiness in Adolescents and Young Adults: Causes, Consequences, and Treatment Strategies (Jun. 2005) 115 Pediatrics 6, p. 1779.) Consistent with a previous study finding 7 a.m. to 8 a.m. to be the most treacherous travel time for young drivers (Pack, Pack, Rodgman, Cucchiara, Dinges, & Schwab, Characteristics of Crashes Attributed to the Driver Having Fallen Asleep (Dec. 1995) 27 Accident Analysis & Prevention 6, pp. 769-775), a five year study by the Ohio Department of Transportation released in August of 2011 showed that 7 a.m. is “the most dangerous time for teens driving to school.” (Crashes Involving Teens Triple During Back-to-School (Aug. 23, 2011) Ohio Department of Transportation.) Given that the sleep-inducing hormone, melatonin, pressures adolescents to sleep until approximately 8 a.m., these outcomes should not be surprising. (Later Start Times for High School Students (Jun. 2002) Univ. Minn.) A study published in April 2011 associates early start times in Virginia Beach (7:25 a.m., except one school at 7:20 a.m.) with 41% higher crash rates among teen drivers than in adjacent Chesapeake where classes started at 8:40 a.m. or 8:45 a.m. (Vorona, Szklo-Coxe, Wu, Dubik, Zhao, & Ware, Dissimilar Teen Crash Rates in Two Neighboring Southeastern Virginia Cities with Different High School Start Times (Apr. 2011) 7 J. Clinical Sleep Med. 2, pp. 145-151.) In 1999, school districts in Lexington, Kentucky delayed start times for high school students county-wide by one hour to 8:30 a.m. Average crash rates for teen drivers in the study county in the 2 years after the change in school start time dropped 16.5% compared with the 2 years prior to the change, whereas teen crash rates for the rest of the state increased 7.8% over the same time period. (Danner & Phillips, Adolescent Sleep, School Start Times, and Teen Motor Vehicle Crashes (Dec. 2008) 4 J. Clinical Sleep Med. 6, pp. 533–535; see also, Storr, Sleepy teen pedestrians more likely to get hit, UAB study says (May 7, 2012) Univ. Ala. Birmingham News.) In reviewing the study, John Cline, Assistant Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at the Yale School of Medicine, commented, “Given the danger posed to young people from car accidents this is a strong reason in itself to change school start times.” (Cline, Do Later School Start Times Really Help High School Students? (Feb. 27, 2011) Psychology Today.) Automobile accidents represent the leading cause of death among teenagers, accounting for approximately 40% of teen fatalities annually and billions of dollars in attendant costs. (CDC, Injury Prevention & Control: Motor Vehicle Safety, Teen Drivers: Fact Sheet.) A CDC study published in August 2011 found an association between health-risk behaviors and diminished weeknight sleep in adolescents, corroborating findings from previous studies. (McKnight-Eily, Eaton, Lowry, Croft, Presley-Cantrell, & Perry, Relationships between hours of sleep and health-risk behaviors in US adolescent students (Aug. 5, 2011) Preventive Medicine, 1-3; Pasch, Laska, Lytle, & Moe, Adolescent Sleep, Risk Behaviors, and Depressive Symptoms: Are They Linked? (Mar. 2010) 34 Am. J. Health Behavior 2, pp. 237-248; O’Brien & Mindell, Sleep and Risk-Taking Behavior in Adolescents (2005) 3 Behavioral Sleep Medicine 3, pp. 113-133.) A July 2011 study by University of 4 Nebraska at Omaha criminologists found “preliminary evidence that sleep-deprived adolescents participate in a greater volume of both violent and property crime.... Further, our results indicate that every little bit of sleep may make a difference. That is, sleeping 1 (hour) less (i.e., 7 hours) than the recommended range increased the likelihood of property delinquency, and this risk increased for each hour of sleep missed.” (Clinkinbeard, Simi, Evans, & Anderson, Sleep and Delinquency: Does the Amount of Sleep Matter? (Jul. 2011) J. Youth & Adolescence, p. 926.) In 2009, following a Rhode Island boarding school’s change in start times from 8 a.m. to 8:30 a.m., Dr. Judith Owens found the number of students reporting symptoms of depression declined, confirming outcomes from the Minnesota longitudinal studies (high school start times delayed to 8:30 a.m., Edina, 8:40 a.m., Minneapolis). (Owens, Belon, & Moss, Impact of Delaying School Start Time on Adolescent Sleep, Mood, and Behavior (Jul. 2010) 164 Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 7, p. 613; Wahlstrom, Changing Times: Findings From the First Longitudinal Study of Later High School Start Times (Dec. 2002) 86 Nat. Assn. Secondary School Principals Bull. 633, pp. 3, 13.) Given the relationship between depression and suicidal ideation in adolescents, Dr. Owens commented the finding was “particularly noteworthy.” (Owens, Belon, & Moss, Impact of Delaying School Start Time on Adolescent Sleep, Mood, and Behavior, supra, 164 Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 7, p. 613; see also, Dahl, The Consequences of Insufficient Sleep for Adolescents: Links Between Sleep and Emotional Regulation (Jan. 1999) 80 Phi Delta Kappan 5, pp. 354-359.) Serious consideration of suicide is among the many health-risk behaviors associated with restricted school night sleep in the 2011 CDC study. (McKnight-Eily, Eaton, Lowry, Croft, Presley-Cantrell, & Perry, Relationships between hours of sleep and health-risk behaviors in US adolescent students, supra, Preventive Medicine, pp. 1-3.) Suicide is the third leading cause of death among U.S. adolescents, in recent years accounting for 10% or more of all teen fatalities. (CDC Nat. Vital Statistics System, Mortality Tables.) Recent data put the suicide rate in the general population at 2.7%. (Miniño, Xu, & Kochanek, Deaths: Preliminary Data for 2008 (Dec. 9, 2010) 59 Nat. Vital Statistics Rep. 2.) The adolescent sleep pattern runs from about 11 p.m. to 8 a.m. and is “rather fixed.” (Later Start Times for High School Students, supra, Univ. Minn.) As the National Sleep Foundation points out, only by carefully controlling light exposure, including wearing eyeshades to exclude evening light, have scientists been successful in modifying adolescent circadian rhythms. (Backgrounder: Later School Start Times (2011) Nat. Sleep Foundation.) Waking an adolescent at 7 a.m. is the “equivalent” of waking an adult at 4 a.m. (Carrell, Maghakian, & West, A’s from Zzzz’s? The Causal Effect of School Start Time on the Academic Performance of Adolescents, supra, 3 Am. Economic J.: Economic Policy 3, p. 64.) Joining other Harvard educators in endorsing later start times (e.g., here, here, here, here, here, pp. 382-383), Professor of Sleep Medicine Susan Redline advises that 7:30 a.m. and 8 a.m. classes begin too early for adolescent students to obtain sufficient sleep and serve to interrupt REM sleep. (Powell, Bleary America needs some shut-eye: 5 Forum points to schools, hospitals, factories as ripe for sleep reform (Mar. 8, 2012) Harvard Science.) Brown University’s Mary Carskadon refers to early school start times as “just abusive.” (Carpenter, Sleep deprivation may be undermining teen health (Oct. 2001) 32 Am. Psychological Assn. Monitor 9.) In 2009, scientists writing in the journal Developmental Neuroscience succinctly stated the uniformly held position of sleep experts on school start times: “For policy makers, teachers and parents, these results provide a clear mandate. The effects of sleep deprivation on grades, car accident risk, and mood are indisputable. A number of school districts have moved middle and high school start times later with the goal of decreasing teenage sleep deprivation. We support this approach, as results indicate that later school start times lead to decreased truancy and drop-out rates.” (Hagenauer, Perryman, Lee, & Carskadon, Adolescent Changes in the Homeostatic and Circadian Regulation of Sleep, supra, 31 Developmental Neuroscience 4, p. 282.) School leaders have a unique capacity to shape the lives of students. (See, Park, Falling Asleep in Class? Blame Biology (Dec. 15, 2008) CNN.) The time of day when school begins is different than other issues in education — it has the potential to implicate adolescent morbidity and mortality. (Sleep Experts Concerned About St. Paul Start Time Change (Jun. 3, 2011) CBS; Vorona, Szklo-Coxe, Wu, Dubik, Zhao, & Ware, Dissimilar Teen Crash Rates in Two Neighboring Southeastern Virginia Cities with Different High School Start Times, supra, 7 J. Clinical Sleep Med. 7, pp. 145-151.) Physicians have been urging school administrators to “eliminate early starting hours for teenagers” since at least 1994. (Minn. Med. Assn. Letter to Superintendent Dragseth (Apr. 4, 1994) Edina Pub. Schools.) It’s long past time to start listening. Yours truly, Your Name/Title/Affiliation (Consider citing the reader to some or all Start Time Recommendations, etc. (html, docx, or pdf), perhaps in lieu of the foregoing letter.) 6