III. Randomness in Law

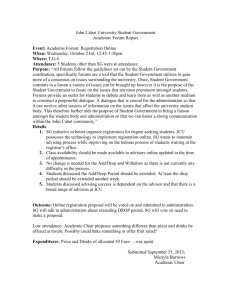

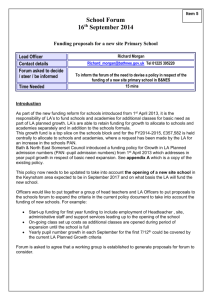

advertisement