Decay theory

advertisement

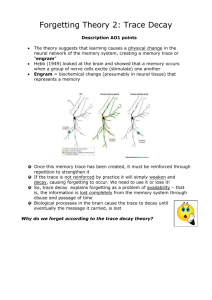

Decay theory Obviously memories are stored somewhere, and the obvious place is the brain. Decay theory assumes that memories have a physical or biological basis in the brain, and that the encoding of memories involves a structural change in the brain. The physical representation of a memory is called a memory trace or an engram. This theory sees forgetting as the physical breakdown or decay of the memory trace. Assuming that rehearsal does not take place, the mere passage of time will cause the memory trace to break down. This explains why forgetfulness increases with time. According to the theory, metabolic processes happen over time which causes the structural change to break down if it is not maintained through repetition. Hebb (1949) argues that during learning that the engram which is formed is timid and fragile. With learning (repetition), it grows stronger until a constant engram is formed through neurochemical and neuroanatomical changes. According to the theory, short term forgetfulness happens because the active trace is disturbed. Peterson & Peterson (1959) provides evidence for this theory. They discovered that if participants were prevented from rehearsing a list of words, their recall dropped from 80% after 3 seconds, to 20% after 18 seconds. In terms of decay theory, the engram could not grow stronger and so broke down. Similarly Watkins et al (1973) asked participants to either listen to and remember notes, or listen to them, hum and identify them before being asked to recall them. He found that participants who had been asked to hum and identify the notes recalled fewer, presumably because this task had prevented rehearsal, and the memory trace had decayed. Decay Lashley (1931) investigated whether by making physical alterations to the brain, he could induce forgetting. If this was the case, then it would suggest that memory has a physical basis and that forgetting is a result of the decay of the memory trace. He trained rats to learn mazes, and then removed sections of their brains. He found a relationship between the amount of brain removed, and the amount of forgetting. This supports decay theory. Evaluation: Issues of ecological validity. Generalisability from rats to humans. Alternative explanations for results However, if decay was the only explanation for loss of memories from LTM, we would expect that all memories would decay at approximately the same rate, regardless of what happened in the intervening time. However in a study by Jenkins & Dallenbach (1924) participants who were asked to recall a series of nonsense syllables after being asleep for eight hours were able to remember many more than those who had been awake for eight hours. If decay theory was correct, we would expect the same amount of forgetting from both groups. Decay therefor cannot be the only explanation. Something else must be affecting forgetting. Evaluation: Generally, there is little support for decay theory, as it cannot explain how we are able to remember things from many years ago. For example, flashbulb memories seem to be immune to decay, even though the memory has not been rehearsed. Interference According to this theory there are two types of interference. Proactive interference is when previous learning interferes with later learning. Retroactive interference is when later learning disrupts earlier learning. For example, if you learned a set of facts about India, and I then asked you to learn a set of facts about China, you could experience interference in one of two ways. The facts about India could disrupt your learning of China (proactive interference) or the new facts about China could alter what you know about India (retroactive interference). A common everyday example of proactive interference is when you rearrange the location of items in a room. You may keep going back to the place where items used to be instead of where they are now! Underwood &Postman (1960) used a paired associate learning task to test the effect of interference. Participants are asked to learn a series of word pairs, so that they can be presented with the first word (the stimulus word), and recall its paired word (response word). They are then given another list of word pairs to learn which have the same stimulus word, but a different response word. Participants have their recall tested on either the first or second list of words. As expected, recall of the response words is poorer, and affected by both previous learning (proactive) and later learning (retroactive). However, this effect is only present when the same stimulus words are used in both lists. Evaluation: Like decay theory, interference theory is a very limited explanation of forgetting. Research suggests that interference only plays a part when the two stimuli are very similar. How often would this apply to real life? A study by Tulving & Psotka (1971) initially seemed to provide evidence for interference. Participants were asked to learn a list of words which were in categories (such as, animals, furniture etc). When asked to free recall the words, as those who had only learned a few categories were able to recall a higher percentage than those who had many. This suggests that retroactive interference of the later words was causing the unlearning of the early words. However, when the participants were given the category names, recall for all participants increased, regardless of how many categories they has to learn (see textbook photocopy pg 54 for a more detailed description of this study). This cannot be explained by interference alone. Another explanation is needed. Cue dependent forgetting This theory states that forgetting is not due to the loss of a memory, but rather is due to the inability to access that memory. This is known as retrieval failure. The memory is still there, but it is inaccessible. The reason that it is unavailable is because you do not have the right cue. For example, if I asked you what Freud’s first name was, you might not be able to access that piece of information. However, if I said it began with “S”, that may be enough of a cue for you to access the name “Sigmund”. Cues can either be external (something about the environment or context) or internal (something about your own state or mood). Context dependent learning (external) was demonstrated by Abernethy (1940) who found that students who sat a test in the same room, by the same instructor as in their normal lessons got higher marks. Presumably, the environment acted as a cue to memory. It’s not just the environment that can act as a cue to learning. As we looked at in the role of emotion, our internal mental or emotional state can act as a cue. This is state dependent learning. Goodwin et al (1969) found that people who had forgetting things when drunk, could recall those things when drunk again. Miles & Hardman (1998) similarly found that things learned when exercising were better remembered when exercising that when at rest. Cue dependent learning can better explain the results of Tulving & Psotka than interference. Some psychologists believe that all forgetting is cue dependent. It is very difficult to test this hypothesis however, as (similarly to repression) we cannot tell if a memory is simply inaccessible, or is not there. The probability is that a lot of forgetting can be attributed to cue dependent learning, but not all. Emotional explanations of forgetting We looked at some explanations of forgetting when we examined the role of emotion in memory. These are recapped below: Repression is an explanation of forgetting which states that traumatic memories are repressed into the unconscious. Suppression – involves being motivated to forget an event or experience by making a deliberate conscious effort to keep it out of consciousness (p.381-382 Grivas et.al.) Evaluation: Needs to be investigated in laboratory – ethics? Some studies (Baddeley 1990) who exposed subjects to mildly upsetting experience – potential evidence to support repression Your Forgetting revision booklet has an extract from HILL which details further evaluations