SEA TURTLE SPECIES OF THE PACIFIC COAST OF

advertisement

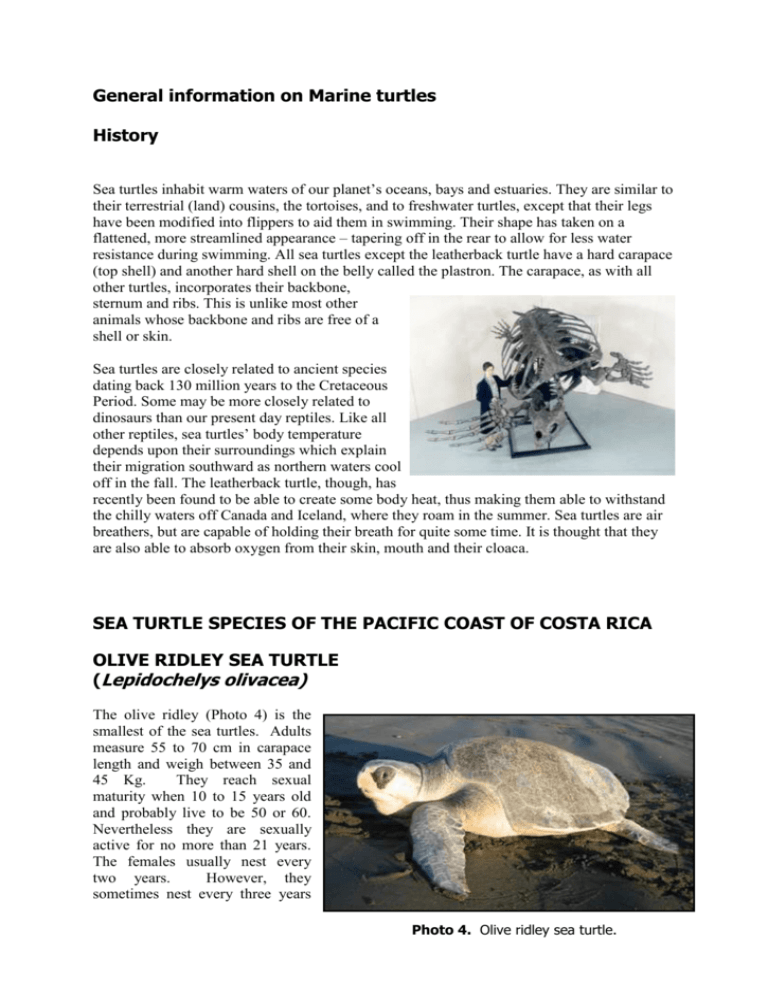

General information on Marine turtles History Sea turtles inhabit warm waters of our planet’s oceans, bays and estuaries. They are similar to their terrestrial (land) cousins, the tortoises, and to freshwater turtles, except that their legs have been modified into flippers to aid them in swimming. Their shape has taken on a flattened, more streamlined appearance – tapering off in the rear to allow for less water resistance during swimming. All sea turtles except the leatherback turtle have a hard carapace (top shell) and another hard shell on the belly called the plastron. The carapace, as with all other turtles, incorporates their backbone, sternum and ribs. This is unlike most other animals whose backbone and ribs are free of a shell or skin. Sea turtles are closely related to ancient species dating back 130 million years to the Cretaceous Period. Some may be more closely related to dinosaurs than our present day reptiles. Like all other reptiles, sea turtles’ body temperature depends upon their surroundings which explain their migration southward as northern waters cool off in the fall. The leatherback turtle, though, has recently been found to be able to create some body heat, thus making them able to withstand the chilly waters off Canada and Iceland, where they roam in the summer. Sea turtles are air breathers, but are capable of holding their breath for quite some time. It is thought that they are also able to absorb oxygen from their skin, mouth and their cloaca. SEA TURTLE SPECIES OF THE PACIFIC COAST OF COSTA RICA OLIVE RIDLEY SEA TURTLE (Lepidochelys olivacea) The olive ridley (Photo 4) is the smallest of the sea turtles. Adults measure 55 to 70 cm in carapace length and weigh between 35 and 45 Kg. They reach sexual maturity when 10 to 15 years old and probably live to be 50 or 60. Nevertheless they are sexually active for no more than 21 years. The females usually nest every two years. However, they sometimes nest every three years Photo 4. Olive ridley sea turtle. and sometimes every year. A single turtle can nest three times in a season with intervals of 17 to 28 days. The nesting season is from June to December. Olive ridleys also nest on beaches in Mexico, Nicaragua, Honduras, Panama, Colombia and are found in the Pacific and Indian oceans. The average depth of their nests is approximately 45 cm and the average number of eggs per nest is approximately 105. Eggs incubate in the nests from 40 to 65 days. Hatchlings measure from 2.5 to 4 cm in carapace length. In Costa Rica the name for olive ridley is “tortuga lora” which translates directly as parrot turtle. They are called this because their beaks resemble a parrot’s beak. They are called “olive ridleys” in English because the color of their shells is olive green. These turtles are omnivores and eat crustaceans, mollusks, fish and some marine vegetation. Olive ridleys especially like to float at or near the surface of the water to warm themselves. In fact the shape of their carapace facilitates absorption of the sun rays. They can dive for up to 30 minutes to depths of 200 m. Only two species of sea turtles, the kemps ridley and the olive ridley, perform the phenomenon known as “arribada”. This occurs when thousands of turtles arrive to nest at one beach at the same time during three or four days, especially when the moon is waning. In Costa Rica there are two beaches, Ostional and Nancite, where olive ridley arribadas occur. Both are in the Guanacaste province and the largest arribadas usually occur between the months of June and December. However, olive ridleys also nest in solitary fashion on the Pacific coast of Costa Rica. Results of research projects indicate very low hatching success rates at arribada nesting sites, apparently due to the high concentration of nesting turtles that mechanically destroy previously laid nests. The massive destruction of eggs fosters the proliferation of fungi and bacteria, affecting egg development and causing very low hatch rates (from 1% to 8%). In contrast, at PRETOMA’s solitary nesting beaches the hatching success is considerably higher, typically over 80%, a fact which draws attention to the contribution of solitary nesters to the maintenance of olive ridley populations. Olive ridleys, like other sea turtles, are in danger of extinction. One of the reasons is the consumption of turtle eggs by humans and animals. Another reason is accidental capture by commercial fishing fleets. These turtles feed on shrimp and are caught in shrimp nets and as they are only able to hold their breath for 15-30 minutes, they drown. They are also accidentally captured on hooks used by commercial longliners. Prefrontal scales Postorbital scales Costal scutes Figure 3. The olive ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) have four prefrontal scales, three pairs of postorbital scales and five to nine costal scutes. GREEN SEA TURTLE (Chelonia mydas) The green turtle (Photo 5) has a carapace of 80 to 100 cm in length and can weigh up to 100 Kg. Green turtles reach sexual maturity when they are 16-25 years old. The females nest every two or three years. A single female can nest up to three times per season with an interval of 12 to 14 days. The nesting season for green turtles on the Pacific coast of Central America is from September to March. Nests are approximately 50 cm deep. The number of eggs per nest ranges from 65 to 87. Eggs incubate in the nests on average 42 to 62 days. Photo 5. Green sea turtle. These nest sporadically on the Pacific coast of Costa Rica on beaches such as Naranjo, Nombre de Jesus, Playa Caletas and Rio Oro among others. Green turtles are for the most part herbivores and feed on algae. They are found in Mexico, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Colombia. Green turtles are endangered principally due to consumption of their meat and eggs. Prefrontal scales Postorbital scales Costal scutes However, they are also captured accidentally by commercial fishing fleets. Over the past few years, dozens of dead green turtles have washed up Pacific beaches in Costa Rica. They have had injuries on their abdomens or evidence of capture in nets and on hooks. HAWKSBILL SEA TURTLE (Eretmochelys imbricata) The hawksbill turtle (Photo 6) has a carapace length of 70 to 95 cm and weighs between 42 and 77 Kg. Females nest every two or three years and in a single season can nest up to five Figure 4. The green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas ) has two prefrontal scales, four pairs of postorbital scales and four costal scutes. times in intervals of 14 to 16 days. The nesting season on the Pacific coast is from May to January. The average number of eggs in each nest is 160. Eggs incubate for 47 to 75 days. The average nest depth is 40 cm. Hatchlings have 3.8 to 4.5 cm carapace length. Hawksbills feed mostly on marine sponges but also consume other invertebrates and algae. Hawksbills are near extinction because Photo 6. Hawksbill sea turtle. their beautiful shells are used for different products and to obtain the shell the turtle must be killed. Their eggs are also consumed by humans. Prefrontal scales Postorbital scales Costal scutes Figure 5. The hawksbill sea turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) has four prefrontal scales, three pairs of postorbital scales and four costal scutes. LEATHERBACK SEA TURTLE (Dermochelys coriacea) The leatherback turtle (Photo 7) is the largest sea turtle and the heaviest reptile on the planet. These turtles are found in the Atlantic and the Pacific. In general, the Pacific leatherbacks are slightly smaller. They weigh between 300–400 Kg and have an average carapace length between 1.4 and 1.8 m. Leatherbacks reach sexual maturity after 10 years. Females nest every two or three years and are able to nest up to six times during a nesting season with intervals of nine days. The nesting season on Pacific beaches lasts from September to March. Photo 7. Leatherback sea turtle. The average number of eggs per leatherback nest is between 80 and 90 with approximately 30 infertile eggs. Average depth of nests is 75 cm. Eggs incubate from 50 to 70 days. Hatchlings have an average carapace length from 5-6.5 cm. Leatherbacks migrate great distances. From their nesting beaches in the tropics they migrate to temperate zones and even sub-polar regions where they have feeding grounds. Satellite tags on these turtles have shown that after nesting in Costa Rica, they migrate south and west to Coco Island and the Galapagos and continue on along the coast of South America all the way to the cold waters of Chile. Of all the sea turtles, leatherbacks are able to dive to the deepest depths – down to 800 m. It is also the fastest swimmer and is able to travel 70 Km per day. Unlike other sea turtles, the leatherback does not have a carapace of bone and scales. Rather their carapace is cartilage, rich in oil with bony plates and covered with skin that is very dark in color with white spots. Their skin is smooth and lacks scales. Leatherbacks are the only turtles capable of regulating their body temperature and maintain it above that of surrounding waters. This allows them to survive in cold waters where they have feeding grounds. Their diet is very specialized as they feed strictly on jelly fish. Leatherbacks’ most important nesting beaches are found in Mexico, Nicaragua and Costa Rica. Unfortunately leatherbacks are disappearing at alarming rates. Playa Grande, in the Leatherback National Park in Costa Rica, is the most important leatherback nesting beach on the Pacific, yet numbers of nesting turtles have plummeted over the past decade. Optimistic estimates put the number of remaining leatherbacks world wide at 30 000. Eastern Pacific Leatherbacks are showing the greatest decline and it is estimated that less than 1000 nesting females are left in existence. This species could be extinct within 10-15 years if something is not done to stop the decline. Longitudinal ridges Figure 6. Head of leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) has no scales, and there are seven prominent ridges along the length of the torso. Life cycle The seven different species of marine turtles inhabit both temperate and tropical regions, utilizing both marine and terrestrial habitats during different phases of their life cycle. Nesting behaviour Female turtles crawl ashore during the night to find an ideal nest location in which to lay their eggs. The female turtle will clear vegetation and other debris away from the chosen areas with her frontal flippers before digging her nest using her hind flippers. Depth of the nest depends on the species of turtle ranging from 40cm to 100cm. Number of eggs laid and size also depends on the species. Once all eggs have been laid the female covers the nest and pats down the sand using her whole body, once satisfied that her eggs are safe she quickly returns to the ocean. Egg development How fast an embryo becomes a hatchling is determined largely by temperature, so nest location is important, shaded nests can take up to 70 days to incubate whereas nests in direct sunlight can take as little as 45 days to hatch. Temperature of the nest is an extremely important part of egg development as it determines the sex of the hatchlings, at 28oc hatchlings develop into males and at 31oc or above they will produce females. Hatchlings After roughly 2 months hatchlings are ready to emerge. It takes 24 to 48 hours for the hatchlings to reach the surface. Hatchlings travel up the nests in groups the hatchlings at the top knock sand from the roof of the nest which filters down to the hatchlings at the bottom that stamp it into the floor of the nest. As this continues the nest rises slowly until they break the surface. In general hatchlings emerge only during the night when temperatures have dropped and the sand is cooler. Visual cues guide the hatchlings from the nest towards the sea following the brighter seaward horizon. Once entering the ocean hatchlings initially orient seawards by swimming into the waves. Experiments have demonstrated that hatchlings can transfer a course initiated on the basis of waves or visual cues to a course mediated by a magnetic compass. After they have entered the ocean little is known about where hatchlings go, it is thought that they migrate drifting pelagically in oceanic gyre systems, this period is known as the “lost years”. Maturity When hatchlings have grown into juveniles sea turtles migrate back to tropical and temperate coastlines where they utilize these habitats to feed and further develop until they have reached maturity, taking between 15-30 years depending on the species. Upon maturity as the nesting season approaches adults start migrating back to nesting beaches, as mating grounds usually lie adjacent to the nesting beach. It is thought that adult sea turtles find their way back to the same nesting beach where they were born by a number of different methods including magnetic navigation, celestial cues, chemical concentrations in sea water and memory of land marks. Once mating has taken place the female crawls ashore to lay her eggs, returning year after year for decades to repeat the process. Threats Harvest for consumption: to date many cultures still consume both sea turtle eggs and meat. Here in Costa Rica it is very common on all sea turtle nesting beaches to encounter people stealing turtle eggs illegally. Ostional is the only nesting beach in Costa Rica where it is still legal to take turtle eggs. In many Central American and Asian countries other parts of the turtle can be used such as the shell, oil and skin. Commercial fishing: trawling and longlining severely effect sea turtle populations annually through incidental capture resulting in high mortality. 250,000 sea turtles are captured annually through trawling 60% of which result in mortality, 15,000 of these are captured in Costa Rican waters. 300,000 turtles are captured annually by long liners of which 5% result in mortality. Marine debris and pollution, Ocean Plastic, hundreds of thousands of sea turtles, whales, other marine mammals and more than 1 million seabirds die each year from ocean pollution and ingestion or entanglement from marine debris. Plastic bags have been well documented to cause mortality in leatherback turtles, as a floating plastic bag can be easily confused as a jellyfish, which is the primary food source of leatherbacks. Coastal Development, - loss and degradation of numerous nesting beaches is occurring through factors associated with coastal development. Beachfront armoring have caused the loss or depleted success of many nesting beaches worldwide. 40% of Florida’s beaches are now classified as critically eroded due to this type of landscape changes. Increased beachfront lighting deters females from coming ashore to nest and disorients newly emerged hatchlings making it more difficult for them to reach the sea. Increased traffic both on the beach and around coastal waters, driving on nesting beaches can cause sand compaction resulting in lower nest success. Driving at night can disturb nesting females and disorientate newly emerged hatchlings. Increased traffic around coastal waters can increase risks of collisions causing severe injuries or mortality in sea turtles. Climate change: Increased atmospheric temperatures will raise sand temperatures affecting the incubation process of sea turtle nests. The sex of hatchlings are determined by nest temperatures, if this increases substantially the ratio of males to females will be considerably effected and could also result in no hatchlings emerging. The increased risk of rising sea levels will considerably effect female turtles as more nesting beaches will become eroded resulted in fewer areas where they can nest successfully.