Fault Separation Gestures Name: As you know, doing Structural

advertisement

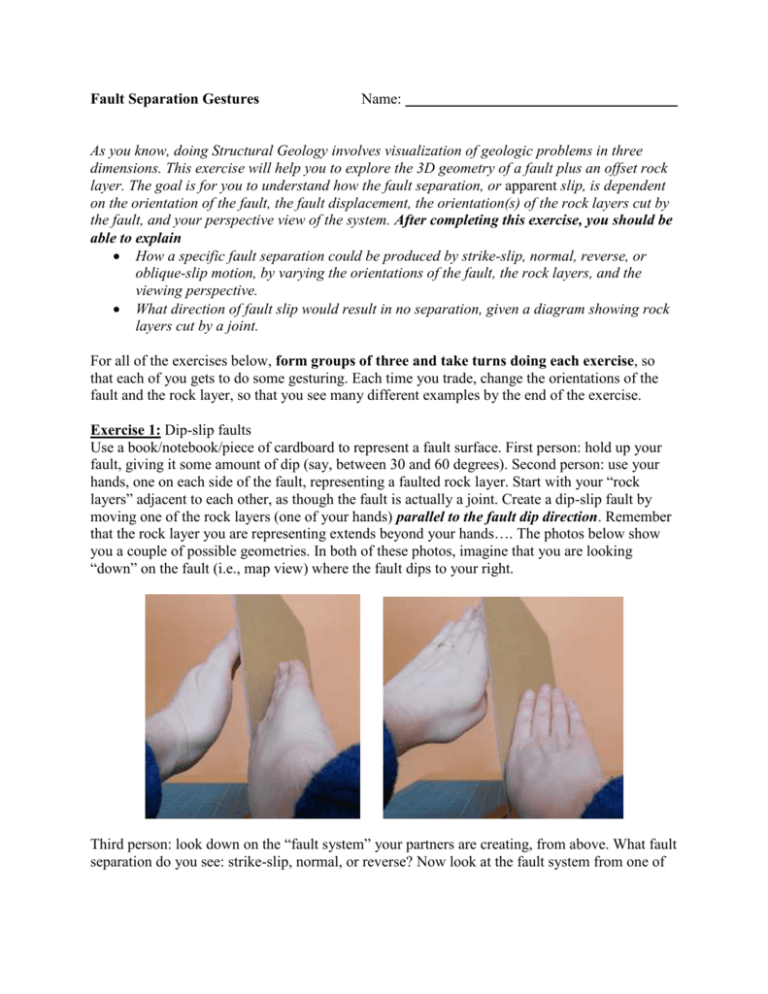

Fault Separation Gestures Name: As you know, doing Structural Geology involves visualization of geologic problems in three dimensions. This exercise will help you to explore the 3D geometry of a fault plus an offset rock layer. The goal is for you to understand how the fault separation, or apparent slip, is dependent on the orientation of the fault, the fault displacement, the orientation(s) of the rock layers cut by the fault, and your perspective view of the system. After completing this exercise, you should be able to explain How a specific fault separation could be produced by strike-slip, normal, reverse, or oblique-slip motion, by varying the orientations of the fault, the rock layers, and the viewing perspective. What direction of fault slip would result in no separation, given a diagram showing rock layers cut by a joint. For all of the exercises below, form groups of three and take turns doing each exercise, so that each of you gets to do some gesturing. Each time you trade, change the orientations of the fault and the rock layer, so that you see many different examples by the end of the exercise. Exercise 1: Dip-slip faults Use a book/notebook/piece of cardboard to represent a fault surface. First person: hold up your fault, giving it some amount of dip (say, between 30 and 60 degrees). Second person: use your hands, one on each side of the fault, representing a faulted rock layer. Start with your “rock layers” adjacent to each other, as though the fault is actually a joint. Create a dip-slip fault by moving one of the rock layers (one of your hands) parallel to the fault dip direction. Remember that the rock layer you are representing extends beyond your hands…. The photos below show you a couple of possible geometries. In both of these photos, imagine that you are looking “down” on the fault (i.e., map view) where the fault dips to your right. Third person: look down on the “fault system” your partners are creating, from above. What fault separation do you see: strike-slip, normal, or reverse? Now look at the fault system from one of the sides. What fault separation do you see from this perspective? (Hint: you should get a different answer!) Take the time to convince yourself that dip-slip motion can result in strike-slip, normal, or reverse separation, depending on the dip of the faulted layers, movement sense, and the direction from which you are viewing it. It may help to move your hands from “unfaulted” positions to “faulted” positions as you think your way through each possibility. When you are convinced that dip-slip motion can produce strike-slip, normal, or reverse fault separation, trade roles and choose a different geometry for your system, and repeat the exercise. Make sure each of you works through several examples before you move on to the next exercise. Exercise 2: Strike-slip faults Use a piece of cardboard (or a book or notebook) to represent a fault surface. First person: hold up your fault so that it is near vertical. Second person: use your hands to represent a rock layer that is displaced by the fault. Start with your “rock layers” adjacent to each other, as though the fault is actually a joint. Create a strike-slip fault by moving one of the rock layers (one of your hands) parallel to the strike of the fault surface. Third person: looking down at the system from above, note what kind of separation is produced. Then look at the faulted layers from the side (looking along the plane of the fault), rather than from above. What is the separation from this new perspective? Is it the same from both sides? Spend a few minutes “playing around” with your rock layers (leave the fault in a fixed position for now) to convince yourself that strike-slip motion can result in strike-slip, normal, or reverse separation, depending on the dip of the faulted layers, movement sense, and the direction from which you are viewing it. It may help to move your hands from “unfaulted” positions to “faulted” positions as you think your way through each possibility. When you are convinced that strike-slip motion can produce strike-slip, normal, or reverse fault separation, trade roles and choose a different geometry for your system, and repeat the exercise. Make sure each of you works through several examples before you move on to the next exercise. Exercise 3: No separation Use a book/notebook/piece of cardboard to represent a fault surface. First person: hold up your fault, giving it some amount of dip (say, between 30 and 60 degrees). Second person: hold two your hands, one on each side of the fault, again representing a faulted rock layer. This time, start with your “rock layers” adjacent to each other, as though the fault is actually a joint. Now move the “rock layer” on one side of the fault in such a way that no separation appears. What kind of slip is necessary to produce that result? Be sure to trade roles and repeat the exercise, choosing a different geometry. Exercise 4 (optional): If you get done early, explore the question of what fault separations you might observe with folded layers cut by a variety of fault geometries.