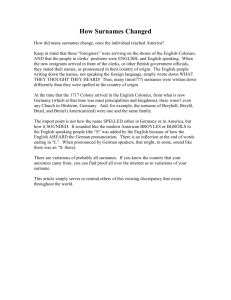

file

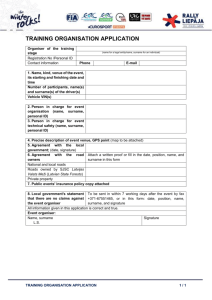

advertisement