Homes, Household Practices, and the Domain(s) of Citizenship

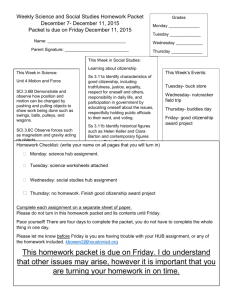

advertisement