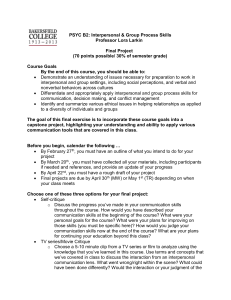

motivation interpersonal

advertisement

INTERPERSONAL INFLUENCE 1 Ashley White April 07, 2014 Dr. Melanie Laliker Interpersonal Influence A definition of interpersonal influence is the use of verbal and nonverbal behaviors to persuade a partner or group towards a decision in which you are enforcing. The human race experiences influence attempts on a daily basis for many instances in life some of which are health, nutrition, and exercise. Within close relationships such as romantic, sexual, teammate, and coach and player relationships, the use of support and persuasion tactics is highly influential. If used in the correct manner, with the right situation, some influence tactics work better than others (Mackert et al. 2011; Otto-Salaj et al. 2008; Thompson et al. 2013; Manne et al. 2011; Gillet et al. 2009; Evans et al. 2012; Blanchard et al. 2009; Standiford 2013). Romantic relationships are often studied in conjunction with health behaviors and an individual’s decision to cease or continue this behavior. There are a variety of topics discussed and researched within romantic relationships such as weight management, nutrition, exercise, cancer, and condoms. Within a romantic dyad, one partner’s use of motivation and negotiation, whether direct or indirect, affects the other partner’s choices and decisions when used in a health and behavior standpoint (Manne et al. 2011;OttoSalaj et al. 2008; Thompson et al. 2013). There are many factors to look at while evaluating and researching the effectiveness of influence attempts between romantic relationships. All of these factors have to do with the actual message such as legitimacy, explicitness, dominance and reasoning. Along with the different meanings behind the message, the influencer must also work on their personal delivery of the message such as their politeness, the others resistance, their use of reward strategies, their referent power attempts, and their use of informational tactics, along with support (Manne et al. 2011;Otto-Salaj et al. 2008; Thompson et al. 2013). Research found that positive influence attempts contained the strategies that involved politeness, lack of dominance, both reward and referent power attempts, and less explicitness. When trying to influence another partner, one must use both nonverbal and verbal negotiation tactics. The choice of nonverbal or verbal depends upon the situation. Regarding some issues such as HIV and condom use, and weight management, the decision of one member of the dyad to negotiate or motivate the other partner, may affect the other partner’s choice to make healthy or unhealthy decisions (Otto-Salaj et al. 2008; Thompson et al. 2013). Many attempts, through a romantic partner, of persuasion and influence, when regarding health and lifestyle issues, can be seen as positive or negative. When using attempts that provide knowledge, information, and reasoning, the receiver of the message will, in most circumstances, change their lifestyle. Such attempts involve someone being more knowledgeable in the field, such as a nurse or a doctor, or someone who has researched the issue and provides many reasons why this would be beneficial to the individual or relationship (Manne et al. 2011;Otto-Salaj et al. 2008; Thompson et al. 2013). According to most research, informational influence strategies typically gain positive influence attempts. As opposed to when a partner attempts to exert their dominance within the relationship and the situation, this then causes the other partner to react negatively, usually resisting and lashing out to the influence attempt; often INTERPERSONAL INFLUENCE 2 increasing the negative behaviors (Otto-Salaj et al. 2008; Thompson et al. 2013). An example of this is a romantic partner putting their relationship on the line due to weight gain and the opposing partner then choosing to do more unhealthy behaviors then gaining more weight. Males and females, according to the research, react differently to certain influence attempts (Mackert et al. 2011; Otto-Salaj et al. 2008). Males react better to reward power attempts such as bribing the person towards something or speaking of what they will gain from this change in behavior; while females, on the other hand, respond better to referent power attempts, which are attempts that show respect and look at the benefits to the relationship rather than what they will gain from this behavioral change (Otto-Salaj et al. 2008). In contrast to Mackert et al. and Otto-Salaj et al., Thompson et al. did not see a gender difference within the responses to the interpersonal influence techniques and situations. Standiford particularly addresses the issues with interpersonal influence and active females. One of the influences among female athletes competition, is that of comparison to male athletes; males naturally have greater speed and skill when it comes to competing in sports. Most active females receive influence and pressure attempts from family members, peers, and even teachers; along with the issue discussed above. Research spoke about how family members can negatively or positively influence a female athletes performance. If their family supports the sport and their diet necessary to excel, takes them to events, pays for events and so on; then the family is then exerting a positive interpersonal influence towards their athlete. As opposed to the latter, family members can also negatively influence their athlete with non-supportive behaviors and actions. Interpersonal influence also greatly affects close relationships regarding things such as health and exercise. Close relationships such as families, friends, and coworkers, address the issues and attempt to change or persuade the issues of physical activity, nutrition, exercise, and overall body health (Mackert et al. 2011). With physical activity, one stays fit, and therefore, in most circumstances, lives a healthier and hopefully longer life. Since exercise is such a huge factor towards our health, most of our close relationships have affects and influence towards this particular subject. In one particular study, they looked into the negative influences regarding interpersonal influence towards exercise and nutrition, one of these influences is known as undermining. Undermining is the use of influence attempts that don’t directly address the situation, but negatively affect the individual being influenced (Mackert et al. 2011). Although undermining is largely affective, in most cases, it can be resisted; one particular situation of this resistance is when undermining is being used about ones need to exercise, but the individual is actually already content with their weight, so the attempts do not affect or influence them in any positive or negative way (Mackert et al. 2011). But, as most researchers have found, every individual factor affects each person and situation completely differently, so it is hard to completely draw conclusions upon these findings. Exercise and physical activity is usually correlated with sports and sports teams, another area that contains a lot of different types of influence attempts. Another instance in which close relationships have high influence rates are those relationships formed within a sports team (Gillet et al. 2009; Evans et al. 2012; Blanchard et al. 2009). A coach and player relationship affects competitors of all levels from peewee to national competitions. National competitors in many sports have spoken of their INTERPERSONAL INFLUENCE 3 positive and negative interpersonal influences from their coaches. Judo competitors, on the national level, in specific, were quoted to have said that their coaches’ support of the athlete’s autonomy positively correlated with their self-determined motivation and performance (Gillet et al. 2009). According to Gillet et al. article; Influence of coaches’ autonomy support on athletes’ motivation and sport performance: A test of the hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, the autonomy coaching style, is one in which the coach focuses on the individual and their abilities and self-motivating behaviors; was seen to be a positive interpersonal influence towards the athlete and therefore directly affecting their competition success. They also can break an athlete down through negative influence attempts such as yelling, ignoring, and exerting their dominance in a negative manner towards the athlete. But coaches are not the only influencers within a sport and team setting. Along with coach and player relationships and their influence, player-to-player or teammate relationships also help positively or negatively influence performance and personal achievements. Whether an individual sport, or a team sport, teammates influence the athlete’s individual performance and dedication to the team. Most athletes, even on individual sports such as track stated in regards to their teams influence on their motivation and performance that “none of them has made it there on their own”(Evans et al. 2012). According to Evans et al. findings the teammates and the team were identified in several aspects of interpersonal influence such as; group as the reason to compete, motivational influences, social comparison, teamwork, and social influences. Teammates are one of the greatest influences in an athlete’s life, due to the fact that the usual athlete spends the majority of their time with their teammates. Most teammates positively influence each other with things such as motivation and support; but there are also negative influences such as comparison to others that can influence their teammate in the wrong way. Interpersonal influence is used daily in many types of relationships and in many situations, it is also something that is researched in depth in many different ways, scenarios, techniques, and situations. The ones addressed in this paper, can be seen as important situations that could result instances of life or death. Cancer screening, HIV prevention, weight management, nutrition, exercise, and competition are all topics spoken about in the above paragraphs. Influence attempts, both negative and positive, come from parents, family members, romantic and sexual partners, friends, teammates, and coaches. There are many routes a person can choose to take while trying to influence another individual, many which lead to completely different outcomes from acceptance and change of behaviors, to resistance and worsening of behaviors. Influence attempts have the ability to build a person up or break someone down. INTERPERSONAL INFLUENCE 4 Works Cited. Evans, B., Eys, M., Wolf, S. (2012). Exploring the nature of interpersonal influence in elite individual sport teams. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 25, 448-462. DOI: 10.1080/10413200.2012.752769 Gillet, N., Vallerand, R., Amoura, S., Baldes, B. (2009). Influence of coaches’ autonomy support on athletes’ motivation and sport performance: A test of the hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 11, 155-161. DOI:10.1016/j.psychsport.2009.10.004. Mackert, M., Stanforth, D., & Garcia, A. A. (2011). Undermining of nutrition and exercise decisions: Experiencing negative social influence. Public health Nursing, 28, 402-410. doi:10.1111/1525-1446.2011.00940 Manne, S., Etz R., Hudson, S., Medina-Forrester, A., Boscarino J., Bowen, D., Weinberg D. (2011). A qualitative analysis of couples’ communication regarding colorectal cancer screening using the Interdependence Model. Patient Education and Counseling, 87, 18-22. DOI:10.1016/J.PEC.2011.07.012 Otto-Salaj, L., Reed, B., Brondino, M. J., Gore-Felton, C., Kelly, J. A., & Stevenson, L. (2008). Condom use negotiation in heterosexual African American adults: Responses to types of social power-based strategies. Journal of Sex Research, 45, 150-163. DOI:10.1080/00224490801987440 Standiford, A. (2013). The secret struggle of the active girl: A qualitative synthesis of interpersonal factors that influence activity in adolescent girls. Health Care for Women International, 34, 860-877. DOI: 10.1080/07399332.2013.794464 Thompson, C., Romo, L., & Dailey, R. M. (2013). The effectiveness of weight management influence messages in romantic relationships. Communication research reports, 30(1), 34-45. DOI:10.1080/08824096.2012.746222