Disaggregating the causes of falling consumption

advertisement

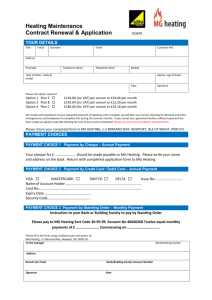

Disaggregating the causes of falling consumption of domestic space heating energy in Germany Dr Ray Galvin1 rg445@cam.ac.uk; Dr Minna Sunikka-Blank mms45@cam.ac.uk Department of Architecture, University of Cambridge, 1-5 Scroope Terrace, Cambridge CB2 1PX, UK Abstract Consumption of domestic heating energy (space and water heating combined) in Germany has been falling in recent years. The most reliable figures indicate it fell by 23% in 2000-2011, from 669 to 515 TWh (temperature adjusted), while the population fell by 2% and the number of occupied dwellings increased by 3.4%. German policy has strongly promoted deep thermal retrofits through regulation, information campaigns and subsidised loans. An important question is what portion of the reductions are due to progressive energy efficiency upgrade policy and what are due to other, non-technical factors such as demographic and behaviour change. We use national statistics and existing empirical studies to disaggregate the contribution of energy-efficiency improvements and non-technical factors to the reduction in consumption. Our analysis suggests that around 13% of the reductions are likely to be due to thermal retrofits of existing dwellings (insulation and new windows); 8% due to boiler or heating system replacements; 1% due to replacement of old dwellings with new, energy-efficient buildings; while over 50% of the savings cannot be explained by these technical improvements. Most of these reductions appear to have occurred in non-upgraded, non-new dwellings. Although we do not know what caused these reductions, the finding is robust to very wide inaccuracies in figures for savings through technical improvements in buildings’ energy-efficiency. More research is needed to explore the extent to which this implies increasing fuel poverty, increasing skills and motivation among non-poor households to heat more economically, or the effects of demographic and lifestyle changes. Key words Home heating behaviour; domestic energy saving; German energy policy; thermal retrofits; heating fuel consumption Highlights 1 German home heating energy consumption fell by 154 TWh in 2000-2011 Approximately 13% of this was due to thermal retrofits of existing homes 8% was due to boiler/heating system upgrades Less than 1% was due to replacement of old with new stock Over 50% came from homes with no energy-efficiency upgrades This could imply rising fuel poverty or more skilful heating behaviour Corresponding author 1 Disaggregating the causes of falling consumption of domestic space heating energy in Germany 1. Introduction There has been a steady fall in heating energy consumption (including both space and water heating) in the German domestic sector since this peaked in the year 2000, reducing from 669 TWh to 515 TWh, or 23%, from 2000 to 2011 in temperatureadjusted figures (Destatis, 2010; 2013). This reduction, of 154 TWh, indicates that German householders spent €12 billion less on heating fuel in 2011 than they would have if their consumption had stayed steady at the 2000 level, and caused around 30 million tonnes less CO2 emissions, even though the number of occupied dwellings increased by 3.4% in 2000-2011. The 2.8 million new dwellings constructed during this period were built to high energy-efficiency standards, while about half that number of older, less energy-efficient buildings became unoccupied. Meanwhile approximately 4 million existing homes benefited from thermal retrofits, including insulation and/or window replacement, and the heating systems in 5.5 million dwellings were upgraded to newer, more energy-efficient models. These improvements resulted partly from the legal requirement in the Energy-Saving Regulations (Energyeinsparverodnung - EnEV), introduced in 2002, to undertake thermal improvements whenever a portion of a building envelope is being repaired or replaced (EnEV, 2009); partly from new regulations concerning boilers; partly from a series of well-funded, persistent government campaigns to encourage and persuade homeowners to thermally upgrade their buildings; and partly from the effect of subsidies from the German Development Bank (Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau – KfW) (DENA, 2009; 2012; UBA, 2010). There has been no attempt to quantify the proportions of domestic heating fuel savings being made from non-technical as compared to technical measures. By ‘nontechnical’ we include such things as demographic changes, which might result in empty rooms in large homes; lifestyle changes, such as people spending less time in the home; and behavioural changes, such as households’ attempts to keep heating consumption low by heating or ventilating more efficiently. Rehdanz (2007) noted that it would be useful to disaggregate these proportions, and Gram-Hanssen (2010; 2011) argues from empirical evidence that both behavioural and technical measures are significant in attempts to lower household energy consumption. The Federal Environment Office (UBA, 2006) surveyed households in 1995-2005 and concluded that changes in user behaviour were making a significantly greater contribution to energy savings than technical, energy-efficiency improvements. Koch et al (2008) investigated the types of user behaviour that would enhance the German government’s domestic heating energy saving goals, while others have surveyed German households to find out what skill and knowledge shortages need to be addressed to enable willing households to reduce heating energy (Brohmann et al, 2000; Hacke, 2007). However, as yet there has not been an attempt to disentangle the various causes of consumption reduction to see what proportion, if any, can be attributed to non-technical measures. This paper considers the possible contribution to domestic heating reductions of technical measures, i.e.: thermal retrofits of existing homes (insulation and window upgrades); boiler or heating system replacement; newly built dwellings; and dwellings becoming unoccupied. We use the term ‘abandoned dwellings’ for the latter, as 2 statistics show that there is no direct correspondence between the numbers of dwellings being demolished annually, and the number of inhabited dwellings becoming unoccupied (Destatis 2004; 2010; 2012). We address the period 2000-2011, as temperature-adjusted consumption peaked in 2000, while 2011 is the most recent year for which reliable data is available. The German Federal Statistics Office (Destatis), the Housing Ministry (BMVBS), the Ministry for the Economy (BMWi), the German Energy Agency (DENA) and the Federal Environment Office (UBA) publish national statistics of heating fuel consumption, the number of new builds, and the number of occupied and unoccupied dwellings. In Germany there are now also a number of credible, existing empirical studies, either peer-reviewed or from major research institutes, that offer empirical findings on other factors that need to be known for a study such as this. These are: the measured heating energy consumption of newly built dwellings; the quantity of living area that has benefited from thermal upgrades; the measured energy consumption savings that have resulted from these upgrades; and the number of boiler/heating system replacements and their increased efficiency. By examining the results of these studies, together with national statistics, we will test the hypothesis that not all the reductions in domestic heating energy consumption in 2000-2011 can be explained by these technical factors. The hypothesis will fail to be confirmed if either (a) the technical factors are seen to have produced sufficient fuel savings to account for the fall in consumption, or (b) uncertainties in the data are so large as to make a clear conclusion impossible. If the hypothesis holds true we will then suggest what other avenues of research would be necessary to identify the nontechnical factors that have been contributing to this steady fall in consumption. Our methodology is set out schematically in Figure 1. The quantities denoted by variables A, B, C, etc., which are displayed on this schematic, are given in Table 1. Other quantities we will be referring to in our analysis are given in Table 2. <INSERT Figure 1> <INSERT Table 1> <INSERT Table 2> Starting at the top right of the schematic in Figure 1: in Section 2 we estimate the number of dwellings newly constructed in 2000-2011 and their total heating consumption in 2011, to give the quantity G. In Section 3 we estimate the total number of dwellings that were ‘abandoned’ in 2000-2011 and their total consumption in 2000, to give the quantity B. Here the word ‘abandoned’ is a mathematical variable equal to the difference between the number of new dwellings built in 2000-2011 and the rise in the number of occupied dwellings in 2000-2011. This is not the same as the number demolished in 2000-2011. The demolition rate bears no direct relation to the rate at which dwellings fall out of use (Destatis, 2004; 2010). It also fails to take account of shifting numbers of unoccupied dwellings that are, for example, between tenants or in under-utilised apartment blocks, for which there are no plans for demolition. A certain number of the new builds can be seen as replacing, one-for-one, the abandoned dwellings, and from this we can work out the number of new builds 3 that were additional to replacements, and the increases in national consumption they caused, i.e. N=G-B. In Section 4 we consider the contribution of thermal retrofits (insulation and new windows; not counting heating system upgrades). To do this we first estimate the number of dwellings retrofitted in 2000-2011 and their pre-retrofit consumption, to give the quantity C. We then estimate their post-retrofit consumption to give the quantity H. The fall in consumption in this sector is given by K= C-H. In Section 5 we estimate the number of dwellings which had boiler or heating system replacements in 2000-2011 and the consequent average percentage energy efficiency increase. The dwellings this affects include both retrofitted and non-retrofitted, so we display the fall in consumption due to boiler/heating system replacement as a separate wedge on the diagram. This consumption in 2000 that was eliminated by 2011 through these replacements is represented by the quantity D. In Section 6 we bring all these figures together to estimate the reductions in consumption in 2000-2011, if any, that were not due to technical factors, namely: L = E – I = (A – B – C - D) – (F – G – H) Equation (1) We draw conclusions from the results of this analysis and make recommendations for policy and further research in Section 7. It should be noted that we are looking at an 11-year time span in this analysis. Our figures refer to the period 1 July 2000 to 30 June 2011, or the 11-year period closest to these dates which each dataset used in the analysis relates to. 2 New builds in 2000-2011 Destatis (2012) figures reveal that 2,689,965 new dwellings were completed in the 11 years from January 2000 to December 2010 (See Table 3). These had an average ‘useful’ area (Nutzfläche)of 114 m2 (Destatis, 2010), giving a total new ‘useful’ area of 306,656,010 m2. ‘Useful’ area includes floor area inside the front door plus a portion of service stairwells, landings, basements and lofts, and is on average 25% larger than ‘living area’ (Wohnfläche), which only includes the floor area within the front door and excludes basements, lofts and internal access stairwells. Following German practice for thermal standards, all calculations of heating fuel consumption given in this paper are based on ‘useful’ area. <Insert Table 3> We now estimate how much these dwellings were consuming in 2011. Prior to October 2002 the average2 maximum permissible heating fuel consumption for new builds was 145 kWh/m2a; from October 2002 to September 2009 it was 100 kWh/m2a; and thereafter 70 kWh/m2a (Galvin, 2012). Federal subsidies led to many homes being designed for higher thermal standards (DENA, 2012a), which would have lowered the average consumption in each of these periods. 2 The Energy Saving Regulations (EnEV) prescribe a range of maximum consumption figures for buildings depending on their geometry, size and connection to other buildings. 4 The most comprehensive peer-reviewed study of the energy performance of new homes built within this period is Greller et al. (2010), though this does not extend through to 2011. These authors analysed the metered consumption of 110,000 gas and oil heated homes built from 1977 to 2006, including 25,650 in the period 2000-2006. They found an average heating fuel consumption of 95 kWh/m2a for those built in the years 2000-2006 inclusive (Greller et al. 2010) and a falling trend from 100 kWh/m2a to 90 kWh/m2a over this period. This implies negligible rebound effect (Haas and Miermayr, 2000; Sorrell and Dimitropoulos, 2008) since minimum standards were tightened to an average of 100 kWh/m2a in 2002. Due to the further tightening of standards in 2009 to 70 kWh/m2a we would expect average consumption to have fallen to this standard or better by 2011. Hence we accept Greller et al.’s (2010) figure of 95 kWh/m2a for 2000-2006 and suggest an average of 65 kWh/m2a for homes built in 2007-2010. Weighting these according to the number of homes built in each of these years gives a total heating consumption in 2011 from all these homes of 26.7 TWh (see Table 3). The three main sources of heating fuel not covered in the analysis of Greller et al. (2010) - district heating, wood and electricity - make up 7%, 7.5% and 3% of heating consumption respectively (Schloman et al, 2004). District heating and wood are associated with primary energy consumption 10% lower than average, and electricity with up to three times its end-energy consumption. Hence the differences here tend to cancel each other out, so we stay with the figure of 26.7 TWh. This is variable G. 3. Dwellings abandoned in 2000-2011 The number of ‘dwellings abandoned in 2000-2011’, as defined above, is equal to the difference between the number of new dwellings built in 2000-2011 and the increase in the number of occupied dwellings in this period. In 2000 there were 35,001,000 occupied dwellings and in 2011 there were 36,198,000, an increase of 1,197,000 (BMVBS, 2012). Since 2,689,965 new dwellings were built in this period, the number of existing buildings that became abandoned (to the nearest 1,000) was 2,689,965 1.197,000 = 1,493,000. There are no existing studies on the heating consumption of dwellings that become unoccupied, but there are good reasons to assume their consumption was higher than the national average. Dwellings become unoccupied for two main reasons in Germany: internal migration; and poor quality of buildings. Migration is the major factor in Germany as there have been large internal population shifts in Germany over the last 20 years, mostly from East to West and North to South (Szymanska et al., 2009). The housing stock in former East Germany was mostly of pre-World War II thermal quality prior to reunification, and the Communist era Plattenbau (prefabricated slab) apartment blocks were of low thermal quality (Flockton, 1998). In the western states emigration occurs mostly from old industrial areas, such as the Ruhr Valley. In regions of falling population such as these, relatively few homes have been built in recent decades. Greller et al. (2010) show that the average consumption of pre-Second World War dwellings is around 165 kWh/m2a and that of dwellings built in 1946-64 around 160 kWh/m2a. Schröder et al (2011), using similar methodology and datasets, estimate total national average consumption at149 kWh/m2a. This would put the consumption of pre-Second-World War dwellings about 5 10% higher than the national average, and as most abandoned dwellings are of older stock, it would seem reasonable to assume their average consumption was around 10% above the national average. As we noted above, the national domestic heating energy consumption in 2000 was 669 TWh and there were 35,505,000 occupied dwellings, so that average consumption was 18,842 kWh/a per dwelling. If the buildings that were later abandoned were consuming 10% above the average, their consumption would have been 20,727 kWh/a per dwelling. As there were 1,493,000 of these dwellings, their total heating consumption in 2000 would have been 28.1 TWh. Hence variable B=28.1 TWh. While this is not essential to our analysis, we note, also, that 1,493,000 of the new builds in 2000-2011 can be seen as replacing abandoned dwellings. This is 56% of all the new builds, hence their 2011 consumption was 56% of 26.7 TWh = 15.0 TWh. Therefore the heating consumption of new builds that were additional to the number of dwellings abandoned was the difference between the total new build consumption of 26.7 TWh and this figure, i.e. 26.7-15.0 = 11.7 TWh. An interesting result here is that the fall in consumption from dwellings being abandoned, at 28.1 TWh, is close to the consumption from new builds, at 26.7 TWh, giving a net reduction of only 1.4 TWh. The net effect of these two sectors on fuel savings is to almost cancel each other out, as there were almost twice as many new dwellings as abandoned dwellings. 4. Dwellings retrofitted in 2000-2011 4.1 General considerations The most difficult part of our analysis is to assess the fuel consumption reductions due to retrofits. Not only are the precise numbers of retrofitted dwellings in dispute, but there is a variety of degrees of retrofit, up to a full project including wall, roof and basement-ceiling insulation; window and door replacement; addition of ventilation system (with or without heat recovery); boiler and radiator replacement (which is considered in the next section); and installation of solar collectors. Further, as there is no inspection of thermal (or other) building standards in Germany, the authorities do not automatically have records of what retrofitting has taken place, and we have observed a certain amount of ‘sub-standard’ retrofitting being carried out illegally. We will consider national summary figures from peer-reviewed papers and from research institutes commissioned by the Federal government. Since it is difficult to get precision in this section, we will estimate the range within which the true value is highly likely to fall, and carry these results forward to our final totals. Further, we will frequently be referring to ‘equivalent dwellings’ rather than ‘number of dwellings’ here, as some studies estimate the savings due to partial retrofits in terms of their equivalent number of dwellings or floor area fully retrofitted. 6 4.2 Annual rate of thermal retrofits The German Energy Agency (DENA) estimates the annual rate of thermal retrofits at 0.8% of the residential building stock per year over the last decade (Stolte, 2011), i.e. 8.8% of the residential building stock over 2000-2011. Since the average number of dwellings (occupied and unoccupied) in 2000-2011 was 39.2 million, this is equivalent to 3.45 million dwellings. Diefenbach et al (2010) found a retrofit rate of 0.83% per year in a survey of 7,500 building owners, equivalent to 9.1% over 2000-2011, or 3.57 million dwellings if extrapolated nation-wide, though this is a limited sample size. Friedrich et al (2007) estimate the equivalent living area of existing homes retrofitted with insulation, new windows in each of the years 2000-2006 as amounting to an accumulated total of 5.9% of the residential stock over these 7 years, which would amount to 9.3% if it continued for the remainder of the 11 years, or 3.64 million dwellings. Weiss et al (2012) estimate an annual retrofit rate for walls at 0.8% and roofs at 1.2%. Weighting walls and roofs according to their average thermal impact3 in the ratio 3:1 would give an annual retrofit rate of 0.84%, assuming windows were upgraded correspondingly. This would amount to 9.24% of the residential stock over 11 years, or 3.62 million dwellings. While the figures from each of these studies do not precisely agree, they are sufficiently close to be used in our analysis. We note their average, of 3.57 million dwellings, with upper and lower bounds 3.64 and 3.37 million dwellings respectively. We will carry forward both upper and lower bound figures in our analysis so as to find whether the degree of imprecision defeats the hypothesis we are testing. 4.3 Pre-retrofit consumption in 2000 We now estimate the heating fuel savings achieved through these retrofits. To begin with, there is no precise data as to their actual pre-retrofit heating fuel consumption. The German Energy Agency targets dwellings with a calculated (i.e. based on the thermal quality of the building) consumption of 225 kWh/m2a or more for retrofitting (Stolte, 2011), but notes that actual consumption in Germany is, on average, 30% below the calculated value (DENA, 2012a: 43). This accords with Sunikka-Blank and Galvin (2012) who find the same figure, and who show that this gap between actual and calculated consumption increases as the calculated consumption increases, i.e. as buildings’ thermal quality diminishes. This would give an actual pre-retrofit consumption of around 160 kWh/m2a. Data from CO2Online’s (www.co2online.de) database of over one million dwellings indicates an average pre-retrofit actual (measured) consumption of 160 kWh/m2a for detached and semi-detached houses, and 150 kWh/m2a for multi-dwelling buildings. The term ‘thermal impact’ means the relative contribution of each feature to the thermal quality of the building, based on the area each contributes to the building envelope, and typical U-values of each. 3 7 However, the self-selection bias of CO2Online’s data might make these actual consumption figures lower than national averages for pre-retrofit dwellings. A further consideration is that many residential buildings in Germany that are thermally retrofitted do not necessarily have especially high pre-retrofit consumption, since thermal retrofitting is compulsory when the substance of the building is being upgraded, rather than when the thermal quality is low (EnEV, 2009). Further, large apartment blocks, which are among the most frequently retrofitted buildings, do not generally have above-average pre-retrofit consumption as the volume to surface area of these buildings makes them inherently more thermally efficient than the average building. Hence it is likely that the pre-retrofit actual consumption of dwellings that were retrofitted in 2000-2011 was not far above the average (149 kWh/m2a), so we will estimate it at 15% above this, at around 170 kWh/m2a. As above, however, we will check at the end of our calculation whether the uncertainties in this figure defeat our working hypothesis. Since the average useable area in 2000 was 110m2 (living area 84m2), this gives a heating fuel consumption of 65.6 TWh for dwellings that were retrofitted in 20002011. Hence our variable C=65.6 TWh, though it could be 10% higher or lower than this (59.0 to 72.2 kWh/m2a). 4.4 Consumption reduction per retrofitted dwelling We now estimate the reduction in heating fuel consumption achieved through these thermal retrofits. Schröder et al (2011) investigated the heating energy consumption of residential buildings of two or more dwellings throughout Germany for 2004-2008. Buildings retrofitted or constructed since 1995 showed an average consumption of 110 kWh/m2a, while those constructed prior to 1995 and not subsequently retrofitted consumed an average of 145 kWh/m2a – a difference of 35 kWh/m2a, or 24%. A further nation-wide empirical study (Schröder et al, 2010) gives cumulative frequency distribution curves for the heating energy consumption throughout Germany of retrofitted and non-retrofitted apartment blocks of floor area larger than 700 m2. The mean is 140 kWh/m2a for those completely non-retrofitted and 90 kWh/m2a for those comprehensively thermally retrofitted, a fuel saving of 50 kWh/m2a, or 36%. Regarding smaller buildings, Walberg et al (2011) investigated the nationwide retrofit performance of 5 classes of 1-2 dwelling buildings and found an average measured consumption reduction of 26%. A comprehensive figure is offered by Tschimpke et al (2011), of an average of 38% reductions achieved through retrofits of all building types, though this refers to calculated, rather than actual, pre-and post-retrofit consumption figures. Clausnitzer et al. (2009; 2010) estimate the calculated saving in retrofits with Federal subsidies from the German Development Bank (KfW) at an average of 33%. If actual pre-retrofit consumption is, on average, 30% lower than calculated consumption (see above), the actual savings for both these studies would be significantly lower. 8 The German Energy Agency also estimates actual savings at 25% (DENA 2012b). Figures from CO2Online indicate actual savings of around 33%, though this could be higher than the national average due to self-selection bias in the data. However, we cannot ignore Schröder et al.’s (2010) figure of 36% for large apartment blocks. Hence we would suggest a mean of around 30% savings for equivalent comprehensive retrofits carried out in 2000-2011, though this could be as large as 35% or as little as 25%. We now bring these percentages together with the pre-retrofit consumption range estimated above. The maximum reduction would arise if the maximum pre-retrofit consumption were reduced by the highest of these percentages, i.e. 72.2 TWh reduced by 35%, a reduction of Hmax=25.3 TWh. The minimum reduction would arise if the minimum pre-retrofit consumption were reduced by the lowest of these percentages, i.e. 59.0 TWh reduced by 25%, a reduction of Hmin= 14.8 TWh. The mid-point between these is Hmid=20.1 TWh. 5. Replacement of boilers and heating systems To calculate the reductions in heating energy consumptions due to replacement of boilers/heating systems we count the number of new boilers and heating units sold to the domestic sector, and take an average figure for the increase in efficiency of each unit. Table 4 shows the number of new boilers or heating units sold in Germany in the years 2000-2009 according to their type (e.g. gas condensing boiler; heat pump), with a composite estimate for 2010. Totals for residential and non-residential new builds are also shown. Subtracting the number of new builds (residential plus nonresidential) completed each year from the total number of heating units sold each year gives an estimate of the number of non-new dwellings that had new heating units installed in the 11 years 2000-2010 inclusive, i.e. 5,162,000. This is 14.0% of the total of 36,198,000 occupied dwellings in 2011. The average efficiency improvement of new heating units in this period is estimated at 18% by CO2online (Heimann, 2012), and this accords with figures from UBA (2011: 97). Hence the overall increase in heating efficiency of the existing German building stock due to these replacements can be estimated as 14.0% of 18%, i.e. 2.52%. The consequent reduction in heating energy consumption would have consequently been slightly more than this, due to the peculiarities of the mathematics of increases in efficiency. Starting from an average boiler/heating system efficiency of 82.27% in 2000 (calculated from UBA, 2011: 97), an efficiency increase of 2.52% represents a rise to 84.79% by the beginning of 2011. Hence, to get the same level of energy services in 2011 as in 2000, the German residential building stock needed to consume only 82.27/84.79 = 0.9703, or 97.03% of the energy it consumed previously, a reduction of 2.97%. However, the rebound effect, or price elasticity of demand for heating fuel, must be considered here, as studies consistently show that when energy services become cheaper, consumers take more of them, and vice-versa. (Haas, 2000; Sorrell and 9 Dimitropoulos, 2008). Estimates of price elasticity of demand for domestic heating in Germany vary from around -0.2 to around -0.5 (e.g. Madlener and Hauertmann, 2011; Rehdanz, 2007), so we take a middle value of -0.35. This means that for every 1% fall (or rise) in the price of heating energy services, the amount of energy service taken increases (or decreases) by 0.35%. This would imply that 65% of this saving of 2.97% is realised, i.e. 1.93%. In short, the effect of boiler/heating system replacements throughout Germany in 2000-2010 inclusive resulted in an estimated heating fuel consumption reduction of 1.93% for the whole country’s residential building stock, compared with 2000 levels, by 2011. Total heating energy consumption in 2000 was 669 TWh, and 1.93% of this is 12.9 TWh. Hence we estimate that the replacement of boilers/heating systems in existing buildings in 2000-2010 inclusive resulted in a saving in 2011 of 12.9 TWh. This is variable D. 6. Reductions due to non-technical or unexplained factors We now have sufficient information to estimate the savings in 2000-2011 that are not explained by thermal retrofits or new builds. These are represented by the variable L, where (recalling Equation 1): L = E – I = (A – B – C - D) – (F – G – H) = (A – B – D – F + G) – (C – H) The values for A, B, D, F and G are known to a high degree of certainty. For C and H we have estimated upper and lower bounds and a middle, or most likely value. The highest value of C together with the lowest value of H will give the lowest estimate for L: Lmin = (669 – 28.1 – 12.9 – 515 + 26.7) – (72.2 – 14.8) = 82.3 TWh. The lowest value of C together with the highest value of H will give the highest estimate for L: Lmax = (669 – 28.1 – 12.9 – 515 + 26.7) – (59.0 – 25.3) = 106.0 TWh. This suggests that heating fuel reductions in 2000-2011 that are not attributable to retrofits, heater/boiler upgrades or new builds are most likely to be in the range 82.3106.0 TWh. This would represent 53.4 - 68.8% of the total reductions, or a middle value of 61.1%. The percentage fall in consumption within this sector would be: Q = 100 x (E – I) / E = 100 x [(A – B – C – D) – (F – G – H)] / (A – B – C – D) 10 The lowest estimate would result from the highest value of C and the lowest of H, i.e. 14.8%. The highest estimate would result from the lowest value of C and the highest of H, i.e. 18.6%. Table 5 gives all the quantities of heating fuel calculated. <Insert Table 5> The price of heating fuel rose by 58.9% during this period (BMWi, 2011; 2011a). The reductions that are not due to technical factors, i.e. 14.8-18.6% of their 2000 value, would therefore represent a long-run fuel price elasticity of demand of -0.25 to -0.32 in respect of heating consumption reductions that were not due to technical measures. This range accords with the lower band of fuel price elasticities reported above. 7. Discussion and conclusions There is a wide range of uncertainty in two of our variables: the pre- and post-retrofit consumption of homes that benefitted from thermal retrofits in the 11 year period. This leads to a wide range of uncertainty in the quantity of energy saved through thermal retrofits carried out in the 11 year period, i.e. 14.8-25.3 TWh. However, this range is not so great as to swamp the likely range of values of residual consumption reductions that do not seem to have come from technical changes4. As we have seen, allowing for the highest estimate of savings through retrofits still leaves a gap of 82.3 TWh or 53.4% of the total reductions that does not seem to be explained by any of the technical measures considered. This gap could be as large as 106.0 TWh, or 68.8% of the total reductions, if the reductions though retrofits were at the smaller end of the range. Hence we can conclude that our hypothesis stands, namely, that not all the reductions in domestic heating energy consumption in 2000-2011 can be explained by technical factors. It appears that a considerable portion – possibly well over 50% - are not explained by the effects of thermal retrofits, replacement of boilers/heating systems, or the replacement of abandoned dwellings with new builds. However, this does not imply that all the unexplained reductions took place in homes that had no retrofits or boiler replacements. Some of the reductions could have taken place in homes which also produced reductions from technical upgrades, and some could have taken place in new builds. The figures merely imply that a large proportion of the reductions seem to have occurred as a result of non-technical factors, without prejudice to which sort of homes these factors pertained in. Nevertheless, since homes that had little or no technical improvement consumed the largest amount of heating energy, these were most likely the homes in which the largest reductions through non-technical means took place, even if every home made the same proportional contribution to non-technical reductions. A 14% reduction in a 1950s home consuming 20,000 kWh per year is much greater than a 14% reduction in a low-energy house consuming 4,000 kWh per year. An anonymous reviewer has pointed out that: ‘ the methodology has some strong limitations, however is acceptable given the lack of detailed information required for such an assessment. Even with the limitations, the analysis gives a good idea about the directions and magnitudes of different components of decline of heating in German buildings' 4 11 A further interesting point is that the reductions due to replacement of abandoned dwellings with new builds appear to be very small, at 1.4 TWh, or 0.9% of the total reductions. This is because nearly twice as many new homes were built in 2000-2011 as the number that were abandoned, even though the population fell in 2000-2011 from 82.2 to 81.8 million (BMVBS, 2012). This accords with the demographic trend of smaller households. Average household size fell during this period from 2.16 to 2.02 persons per household (BMVBS, 2012). This trend should lead to caution in predicting that significant nationwide reductions in domestic heating energy consumption are likely to result from increasing the rate of construction of new builds (though there may be other good reasons to increase this rate). Our analysis has shown that significantly greater reductions have come from both thermal retrofits and heating system upgrades. It remains to be asked what factors might be causing the large reductions that are not explained by technical factors. To begin with, demographic trends seem to play a role. The reduction in household size implies that many existing homes are becoming emptier: the number of bedrooms in Germany is increasing as the population is falling. This suggests that many homes had more empty rooms in 2011 than they had in 2000. It would seem to follow that many of these householders would now heat less of their living area, and possibly also for less time per week, because with fewer occupants a house is likely to be empty more often and for longer periods. In a sense, many old homes are exporting some of their heating consumption to new builds, as former household members take up residence in them. A further factor is price elasticity of demand for heating fuel. With studies consistently showing elasticities of between -0.2 and -0.5, this implies that households, on average, reduce their consumption in response to fuel price rises. One concern here is that this could be leading to fuel poverty. The German Energy Agency’s analysis of the heating consumption of a sample of 35,000 German homes shows that actual consumption is, on average, 30% lower than dwellings’ calculated energy rating (DENA, 2012a). This accords with Sunikka-Blank and Galvin’s (2012) analysis, which adds that the percentage gap increases considerably for the less energy-efficient homes. This lends weight to the suggestion that households take less energy services when the cost is high. Some of the datasets in Sunikka-Blank and Galvin’s (2012) analysis show very low consumption for some homes with very high energy ratings, indicating that many people could be failing to heat their homes adequately. However, these non-technically induced reductions might also indicate that some households are becoming more skilled at getting the level of energy services they want, without consuming a great amount of fuel. These households may be heating fewer rooms, or for shorter periods, or to lower temperatures, or some combination of these, than they used to, or ventilating less adequately, a possibility explored in Galvin (2013). Some households may be motivated by economic thrift, environmental concern, or other factors we about which we do not yet have clear knowledge. It might be possible to learn from such people since, as some of the works cited above appear to have found, user behaviour plays just as important a role in heating energy consumption levels as technical measures play. More research is needed to identify the reasons for this steady reduction in heating energy consumption, particularly 12 among less energy-efficient homes, and whether it indicates increasing fuel poverty, smart heating skills, or some combination of these in Germany. Finally, the results of this paper suggest that Germany is saving considerable sums of money through non-technical causes of heating fuel consumption reduction. The 82.3106.0 TWh saved in this way equate to a saving of around 6.6-8.5 billion euros in 2011, and 16.5-21.2 million tonnes of avoided CO2 emissions. These considerable savings would tend to support the suggestion that the specific causes of nontechnically induced heating fuel reductions should be systematically investigated. References BMVBS (Bundedsministerium für Verkehr, Bau und Stadentwicklung) (2012) Wohnen und Bauen in Zahlen 2011/2012. Available at http://www.bmvbs.de/SharedDocs/DE/Publikationen/BauenUndWohnen/wohnen-und-bauen-inzahlen-2011-2012.html Accessed 3 March 2013. BMWi (Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Technology) (2011). Zahlen und Fakten: Energidaten: Nationale und Internationale Entwicklung, Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Technologie, Referat III C 3., 2011 Available at http://www.bmwi.de/BMWi/Navigation/Energie/Statistik-undPrognosen/energiedaten.html Accessed 5 December, 2010. BMWi (Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Technology) (2011a). Energiedaten: ausgewählte Grafiken; Stand: 15.08.2011a. Available at http://www.bmwi.de/BMWi/Navigation/Energie/Statistikund-Prognosen/energiedaten.html Accessed 14 December 2011. Brohmann, Bettin; Cames, Martin; Herold, Anke; Boschmann, Nina (2000). Klimaschutz durch Minderung von Treibhausgasemissionen im Bereich Haushalte un Kleinverbrauch durch klimagerechtiges Verhalten, Band 1: Private Haushalte, 2000. Darmstatt, Berlin and Freiburg: Institut für angewandte Ökologie. Available through the German National Library of Science, http://www.opengrey.eu/partner/tib Electronic copy supplied courtesy of Institut Wohnen und Umwelt (http://iwu.de) Clausnitzer KD, Gabriel J, Diefenbach N, Loga T, Wosniok W (2009) Effekte des CO2Gebäudesanierungsprogramms 2008. Bremer Energie Institut, Bremen Clausnitzer KD, Fette M, Gabriel J, Diefenbach N, Loga T, Wosniok W (2010) Effekte der Förderfälle des Jahres 2009 des CO2-Gebäudesanierungsprogramms und des Programms „Energieeffizient Sanieren“. Bremer Energie Institut, Bremen DENA (Deutsche Energieagentur) (2009). Machen Sie Dicht: Energie Einsparen in Gebäuden: Mit wenig Aufwand viel erreichen: Richtig heizen, dämmen, lüften. Pamphlet available online at www.zukunft-haus.info; www.dena.de Accessed 20 November, 2011. DENA (Deutsche Energie-Agentur) (2012). Thema Enegie: Lüftungsarten: Nicht zu viel und nicht zu wenig - Lüftung mit Technik. Web portal. http://www.thema-energie.de/heizung-heizen/lueften-kuehlen/lueftungsarten.html Accessed 7 April, 2012 DENA (Deutsche Energie-Agentur) (2012a) Der dena-Gebäudereport 2012: Statistiken und Analysen zur Energieeffizienz im Gebäudebestand. Berlin: Deutsche Energie-Agentur. Available online via: http://www.dena.de/publikationen/gebaeude/report-der-dena-gebaeudereport-2012.html accessed 20 February, 2013. DENA (Deutsche Energie-Agentur) (2012b) Energieeffiziente Gebäude. http://www.dena.de/themen/energieeffiziente-gebaeude.html. Accessed 26 Sept 2012 13 Destatis (Statistisches Bundesamt Deustschlands) (2004). Bautätigkeit und Wohnungen: Bestand an Wohnungen; Fachserie 5 / Reihe 3, 2004. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt. Destatis (Statistisches Bundesamt Deustschlands) (2010) Energieverbrauch der privaten Haushalte für Wohnen rückläufig: Pressemitteilung Nr.372 vom 18.10.2010. Statistisches Bundesamt, Wiesbaden. http://www.destatis.de/jetspeed/portal/cms/Sites/destatis/Internet/DE/Presse/pm/2010/10/PD10__372_ _85,templateId=renderPrint.psml. Accessed 28 Jan 2012 Destatis (Statistisches Bundesamt Deustschlands) (2012) Bauen und Wohnen: Baugenehmigungen / Baufertigstellungen; Lange Reihen z. T. ab 1949. Available at https://www.destatis.de/DE/Publikationen/Thematisch/Bauen/BautaetigkeitWohnungsbau/Baugenehmi gungenBaufertigstellungen.html Accessed 3 March, 2013. Destatis(Statistisches Bundesamt Deustschlands) (2013) Energieverbrauch für Wohnen 2005-2011. Web resource: https://www.destatis.de/DE/ZahlenFakten/GesamtwirtschaftUmwelt/Umwelt/UmweltoekonomischeGe samtrechnungen/EnergieRohstoffeEmissionen/Aktuell.html Accessed 3 March, 2013 Diefenbach N, Cischinsky H, Rodenfels M, Clausnitzer KD (2010). Datenbasis Gebäudebestand Datenerhebung zur energetischen Qualität und zu den Modernisierungstrends im deutschen Wohngebäudebestand. Institut Wohnen und Umwelt/Bremer Energie Institut, Darmstadt. http://www.iwu.de/fileadmin/user_upload/dateien/energie/klima_altbau/Endbericht_Datenbasis.pdf. Accessed 21 Jan 2012 EnEV (2009) Energieeinsparverordnung, Verordnung über energiesparenden Wärmeschutz und energiesparendeAnlagentechnik bei Gebäuden (Text of the German Federal Energy Saving Regulations for Buildings), 2009 http://www. enevonline.org/enev 2009 volltext/index.htm (accessed 22.06.12) Flockton C (1998) Housing situation and housing policy in East Germany. German Politics 7(3): 69-82 Friedrich M, Becker D, Grondy A, Laskosky F, Erhorn H, Erhon-Kluttig, Hauser G, Sager C, Weber H (2007) CO2-Gebäudereport 2007, im Auftrag des Bundesministeriums für Verkehr, Bau und Stadtentwicklung (BMVBS). Fraunhofer Institut für Bauphysik, Stuttgart Galvin R (2012) German Federal policy on thermal renovation of existing homes: A policy evaluation. Sustainable Cities and Society 4: 58-66. Galvin R (2013) Impediments to energy-efficient ventilation of German dwellings: A case study in Aachen. Energy and Buildings 56: 32–40 Gram-Hanssen K (2010) Residential heat comfort practices: understanding users. Building Research and Information 38(2):175–186 Gram-Hanssen K (2011) Households' energy use – which is the more important: efficient technologies or user practices? Paper presented at the World Renewable Energy Congress, Linköping, May 8-13 2011 Greller M, Schröder F, Hundt V, Mundry B, Papert O (2010) Universelle Energiekennzahlen für Deutschland – Teil 2: Verbrauchskennzahlentwicklung nach Baualtersklassen. Bauphysik 32: 1-5 Haas R, Biermayr P (2000) The rebound effect for space heating: empirical evidence from Austria. Energy Policy 28: 403–410. Hacke U (2007). Supporting European Housing Tenants In Optimising Resource Consumption. Deliverable 2.1: Tenant and organisational requirements, Version 1a. Berlin and Frankfurt: Save@Work4Homes. Available at http://www.iwu.de/fileadmin/user_upload/dateien/energie/klima_altbau/SAVE_Work4Homes_Deliver able_2.1_V1a.pdf Accessed 27 October, 2011. 14 Heimann S (2012) Wie viel hat Ihr Kesselaustausch gebracht? Online resource: http://www.heizspiegel.de/news/article/1139/wie-viel-hat-ihre-kesselaustausch-gebracht/index.html Accessed 02 March 2013 Koch A, Huber A, Avci N (2008) Behaviour Oriented Optimisation Strategies for Energy Efficiency in the Residential Sector. Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference for Enhanced Building Operations, Berlin, Germany, October 20-22, 2008. ESL-IC-08-10-72 Madlener R, Hauertmann M (2011) Rebound Effects in German Residential Heating: Do Ownership and Income Matter? RWTH-Aachen University FCN Working Paper No. 2/2011 Rehdanz K (2007) Determinants of residential space heating expenditures in Germany. Energy Economics 29: 167–182 Schloman B, Ziesling H, Herzog T, Broeske U, Kaltschnitt M, Geiger B (2004) Energieverbrauch der privaten Haushalte und des Sektors Gewerbe, Handel, Dienstleistungen (GHD), Project Nr 17/10, Aschlussbericht an das Ministerium für Wortschaft und Arbeit, Karlsruhe: Fraunhofer Institut für Systemtechnik und Innovationsforschug. Available at: http://isi.fraunhofer.de/iside/e/projekte/122s.php Accessed 26 November, 2011. Sorrell S, Dimitropoulos J (2008) The rebound effect: Microeconomic definitions, limitations and extensions. Ecological Economics 65: 636-649 Schröder F, Engler HJ, Boegelein T, Ohlwärter C (2010) Spezifischer Heizenergieverbrauch und Temperaturverteilungen in Mehrfamilienhäusern – Rückwirkung des Sanierungsstandes auf den Heizenergieverbrauch. HLH 61(11): 22-25. http://www.brunatametrona.de/fileadmin/Downloads/Muenchen/HLH_11-2010.pdf. Accessed 8 Dec 2011 Schröder F, Altendorf L, Greller M, Boegelein T (2011) Universelle Energiekennzahlen für Deutschland: Teil 4: Spezifischer Heizenergieverbrauch kleiner Wohnhäuser und Verbrauchshochrechnung für den Gesamtwohnungsbestand. Bauphyisk 33(4): 243-253 Stolte C (2011) The German Experience of Thermal Renovation. Presentation at the Conference Cutting Carbon Costs: Our Big Energy Battle, London School of Economics, London, 8 November 2011 Szymanska D, Sroda-Murawska S, Swiderska K, Adamiak C (2009) Internal migration in Germany in 1990 and 2005. Bulletin of Geography, Socio-economic series 12/2009: 109-120 Tschimpke O, Seefeldt F, Thamling N, Kemmler A, Claasen T, Gassner H, Neusüss P, Lind E (2011) Anforderungen an enen Sanierungsfahrplan: Auf dem Weg zu einem klimaneutralen Gebäudebestand bis 2050. NABU/prognos, Berlin. UBA (Umweltbundesamt) (2006). Wie private Haushalte die Umwelt nutzen – höherer Energieverbrauch trotz Effizienzsteigerungen: Hintergrundpapier November 2006, DessauRoßlau/Berlin: UBA. Available at http://www.destatis.de/jetspeed/portal/cms/Sites/destatis/Internet/DE/Presse/pk/2006/UGR/UBAHintergrundpapier,property=file.pdf Accesses 21 November, 2011 UBA (Umweltbundesamt) (2010). Energiesparen im Haushalt: gut furs Klima, gut furs Portminaie, Dessau-Roßlau: UBA. Available at www.umweltbundesamt.de/energie/sparen.htm Accessed 25 October, 2011 UBA (Umweltbundesamt) (2011) Energieeffizienz in Zahlen: Endbericht. Forschungskennzahl 3708 41 121 UBA-FB 00 1469. Walberg D, Holz A, Gniechwitz T, Schulze T (2011) Wohnungsbau in Deutschland – 2011: Modernisierung oder Bestandsersatz: Studie zum Zustand und der Zukunftsfähigkeit des deutschen „Kleinen Wohnungsbaus“, Arbeitsgemeinschaft für zeitgemäßes Bauen e.V. Kiel. www.arge-sh.de. Accessed 3 March 2012 15 Weiss J, Dunkelberg E, Vogelpohl T (2012) Improving policy instruments to better tap into homeowner refurbishment potential: Lessons learned from a case study in Germany. Energy Policy 44: 406–415 16 Fig 1. Schematic showing the possible contribution of five different factors to the fall in domestic heating consumption in Germany in 2000-2011: abandonment of dwellings; new builds; thermal retrofits (insulation and windows); new boilers/heating systems; and nontechnical influences. energy consumption (TWh) B Dwellings abandoned in 2000-2011 C retrofits new builds D new boilers A G non-technical factors H E F I Non-technical causes (35.505 million 2000 occupied dwellings) 17 (36.089 million 2011 occupied dwellings) Table 1. Quantities of heating energy displayed in Fig. 1. Note that there will be overlap between these categories in some cases. Symbol A B C D E F G H I Quantities of heating fuel consumed Quantities of heating fuel consumed in 2000 by: in 2011 by: All dwellings in 2000 Dwellings abandoned in 2000-2011 Dwellings retrofitted (Insulation & Windows) in 2000-2011 Dwellings with boiler/heating system replacement in 2000-2011 Dwellings not upgraded in 2000-2011 All dwellings in 2011 Dwellings constructed in 2000-2011 Dwellings retrofitted (insulation & windows) in 2000-2011 Dwellings not upgraded in 2000-2011 Table 2. Other symbols, and composites, used in the analysis Symbol Quantity of heating fuel K Savings through thermal retrofits of existing dwellings L Savings made through non-technical means Total Reductions 2000-2009 M Savings through new builds replacing abandoned dwellings Additional consumption through excess of new builds over N abandonments P Net saving through new builds and abandonments 18 Equal to C-H E-I A-F G-B Table 3. Numbers of new dwellings built in Germany in the years 2000-2010 inclusive, giving estimated heating energy consumption based on an average ‘useful’ floor area of 114 m 2 per dwelling, to give an estimate of heating energy consumption in 2011 of all dwellings built in this period. Source: Destatis (2012). year 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Total No. 348340 290978 274117 296823 268679 240571 247793 182771 174691 177570 187632 2689965 Est. heating consumption (kWh/m2a) 95 95 95 95 95 95 95 65 65 65 65 Heating consumption (TWh) 3.773 3.151 2.969 3.215 2.910 2.605 2.684 1.354 1.294 1.316 1.390 19 26.661 Table 4. Sales of new boilers/heating systems in Germany 2000-2009, with estimated figure for 2010, alongside figures for new builds, to give numbers of dwellings with new boilers/heating systems installed in 2000-2010 incusive. Sources: UBA (2011: 96); Destatis (2012) and Statistica: http://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/199380/umfrage/baugenehmigungen-von-wohnungen-seit-2000/ plus own calculations. Totals New units (1000s) Lowtemp (Gas) Lowtemp (Oil) Condensing (Gas) Condensing (Oil) Heatpumps Biomass (central) TOTAL (1000s) New Builds (Residential) 2000 385 218 230 4 9 9 855 348340 2001 314 216 248 8 13 9 808 2002 271 188 254 11 13 14 751 2003 245 180 276 14 14 19 748 2004 239 187 307 17 16 28 794 2005 212 164 288 21 19 31 735 290978 274117 296823 268679 240571 2006 152 118 344 39 49 54 756 247793 2007 112 65 271 37 46 19 550 182771 2008 105 47 308 58 62 36 616 174691 2009 109 44 330 72 55 27 637 177570 2010 650 187632 7900 0 2689965 New builds (nonresidential) TOTAL new builds 7610 355950 5473 296451 5189 279306 4259 301082 4054 272733 3600 244171 4143 251936 3872 186643 3360 178051 3293 180863 3148 190780 48001 2737966 new boilers/heating units in old dwellings 499050 511549 471694 446918 521267 490829 504064 363357 437949 456137 459220 5162034 20 Table 5 Estimates of quantities of heating energy for each variable in the analysis Symbol Estimate (TWh) Quantities of heating fuel consumed in 2000 by: Quantities of heating fuel consumed in 2011 by: A 669.0 All dwellings B 28.1 C 59.0 - 72.2 D 12.9 E 555.8 – 569.0 Dwellings abandoned in 2000-2011 Dwellings retrofitted in 2000-2011 (insulation & windows) Dwellings with new boilers/heating systems in 2000-2011 Remaining consumption in 2000 F 515.0 All dwellings G 26.7 Dwellings constructed in 2000-2011 H 14.8 - 25.3 Dwellings retrofitted in 2000-2011 (insulation & windows) I 463.0 – 473.5 Remaining consumption in 2011 M 15.0 N 11.7 (additional) New builds additional to replacements P 1.4 Net saving through new builds and abandonments L 82.3 – 106.0 Reductions due to non-technical factors Changes in quantities of heating fuel 2000-2011 due to New builds replacing abandoned dwellings 21