Aspergers 3rd level - symp1

advertisement

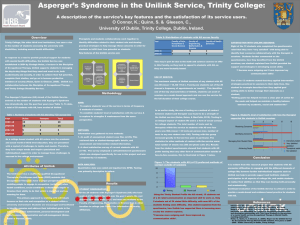

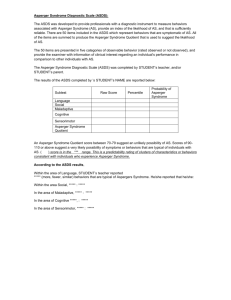

Page |1 Managing Asperger’s Syndrome in Third Level Education Claire Gleeson, Sarah Quinn and Clodagh Nolan University of Dublin Trinity College Unilink Service June 2010 Gleeson C., Quinn S., & Nolan C. Unilink, University of Dublin, Trinity College. Page |2 Abstract Trinity College, like other third level institutions have seen a rise in the number of students accessing the university with disabilities. In particular one of the greatest increases in student numbers attending university are those individuals with Asperger’s Syndrome (AS). Over the past three years the number of referrals for students with Asperger’s Syndrome to the Unilink Service has quadrupled. As a college bound student with Asperger’s Syndrome enters into the academic and social world of third level education, they are presented with a myriad of challenges to tackle and master. The Unilink Service endeavours to provide practical support in managing the challenges and daily occupations of student life. This workshop will provide a review of the literature in relation to the difficulties that individuals with Asperger’s Syndrome encounter. Furthermore the growing and complex needs of these university students with AS will be discussed. Current approaches to support these students with Asperger’s Syndrome will be detailed and finally students’ progress and perspectives will be explored. Gleeson C., Quinn S., & Nolan C. Unilink, University of Dublin, Trinity College. Page |3 Contents Introduction What is Asperger’s Syndrome? Asperger’s Syndrome and the University Experience Third Level Support for Students with Asperger’s Syndrome Profile of Students with Asperger’s Syndrome Utilising the Unilink Service One Student’s Journey through the Unilink Service Student-Outcomes within the Unilink Service Future Directions for the Asperger’s Syndrome Strand of Unilink Conclusion References Gleeson C., Quinn S., & Nolan C. Unilink, University of Dublin, Trinity College. Page |4 Introduction The number of students in Higher Education with a registered disability has risen increasingly over the past number of years (AHEAD, 2008). This increase may be attributed, in part, to the legislation and access policies (Equal Status Acts, 2000-2004; University Act, 1997; Disability Act, 2005 (Government of Ireland)) now in place, as well as the introduction of Disability Services in third level institutions across the country. Trinity College, like other third level institutions, have seen a rise in the number of students accessing the university with disabilities. One of the student groups that has increased most significantly are those with Asperger’s Syndrome (AS) (Nolan, Quinn, & Gleeson, 2009). This upward trend is likely to continue as the identification of AS increases (Wing & Potter, 2002) and access to early interventions improve. What is Asperger’s Syndrome? Asperger’s Syndrome (AS) is a pervasive developmental, neurological disorder (Wing & Gould, 1979; Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright, Stone, & Rutherford, 1999) identified by Hans Asperger, a Viennese paediatrician over fifty years ago (Asperger, 1944). He described children in his practice that lacked non-verbal communication skills, demonstrated limited empathy with their peers, and were physically clumsy (Frith, 1991). Asperger’s Syndrome is at the higher end of the autistic spectrum disorders and is classified as a mental health disorder by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) (APA, 2000). Asperger’s Syndrome can be first diagnosed early in childhood, although individuals are often diagnosed later in life, during teenage and adolescent years (World Health Organisation (WHO), 2006). Individuals with AS are usually of average or above average intelligence. Asperger’s Syndrome affects individuals in different ways. Individuals with AS are said to exhibit characteristics that fall into a triad of deficits, these deficits include difficulties with 1. Verbal and non-verbal communication; 2. Socialisation and developing Gleeson C., Quinn S., & Nolan C. Unilink, University of Dublin, Trinity College. Page |5 relationships; 3. Flexibility of thought processes and imagination (APA, 2000). These difficulties are said to impact on a person’s ability to function. Language & Communication Social and Emotional Diffic Asperger’s Syndrome Flexibility of Thought (Imagination) ( Individuals with Asperger’s Syndrome also tend to exhibit repetitive, stereotypical behaviours and can have an intense preoccupation with narrow subjects, activities and interests (APA, 2000), which may lead an individual with AS to demonstrate exceptional abilities and/or great expertise in a particular area (Morrison, Sansoti & Hadley, 2009). Asperger’s Syndrome differs from other autism spectrum disorders by its relative preservation of linguistic and cognitive development. Although not required for diagnosis, physical clumsiness and atypical use of language are frequently reported (McPartland & Klin, 2006; Baskin, Sperber & Price, 2006). Many individuals with AS often have difficulties with sensory processing and regulation of affect and arousal. They may get overwhelmed by too much sensory information in their environments. Although to date, sensory processing difficulties have not been included within the official diagnostic criteria. Research also shows that individuals with Asperger’s Syndrome have poor organisational skills (Adreon & Durocher, 2007) and may have increased levels of anxiety, stress and also depression. These factors can further impact on their ability to engage with their Gleeson C., Quinn S., & Nolan C. Unilink, University of Dublin, Trinity College. Page |6 activities/occupations and the environments in which these occupations take place (BaronCohen, Wheelwright, Stone, & Rutherford, 1999; Fujikawa, Kobayashi, Koga, & Murata, 1987; Whitehouse et al, 2009). The exact cause of Asperger’s Syndrome is unknown, and is still being investigated, although research suggests cause stems from a combination of genetic and environmental factors (McPartland & Klin, 2006; National Autistic Society, 2010). Internationally, Asperger’s Syndrome is more common in males than females; with an estimated ratio of nine to one males to females in Ireland (ASPIRE, 2009). The identification of AS has not been exclusive to any one social background, nationality, culture or creed. In Ireland it is estimated that several thousand people have Asperger’s Syndrome (ASPIRE, 2009). Asperger’s Syndrome and the University Experience There are many characteristics of AS that can be considered as personal strengths and can enable individuals to achieve high levels of competency and mastery in their areas of interest or productive occupations. It is suggested that famous people that have Asperger’s Syndrome include W.B. Yeats, Albert Einstein and Isaac Newton; it is thought that AS has actually enhanced these people’s capacity for success (Lyons & Fitzgerald, 2005; Walker & Fitzgerald, 2006). The university environment can nurture student’s individual strengths and can foster the development of special interests. It provides opportunities for students to grow on a personal, social and academic level. By third level students are beginning to become more independent; university hold prospects to make new and diverse friendships, to join societies, increase exposure to new activities, and develop a stronger sense of self, values and interests. However, for some students these new and exciting opportunities present as challenges. Madaus (2005) has commented that third level education operates a complicated system Gleeson C., Quinn S., & Nolan C. Unilink, University of Dublin, Trinity College. Page |7 that is very different to that which students have experienced in second level. The transition from a structured, predicable environment in secondary school to the freer environment of higher education is likely to present particular challenges to students with AS (MacLeod & Green, 2009). Typically, university offers less prescribed (no homework) and rote learning, less supervision and demands more in terms of independent study and critical thinking. The social norms and expectations in third level are not explicit in comparison to the stated rules of behaviour and code of dress required at second level. The infrequent contact hours and non-obligatory attendance can impact adversely on the ability of students with Asperger’s Syndrome to make friends and connect with the college community. On a personal level, new living circumstances can present demands on the student who moves away from home where self-management and domestic activities must be addressed. Although not all students with Asperger’s Syndrome experience challenges in third level education, many students will encounter various difficulties with social functioning. Therefore, they may have difficulty making friends, establishing relationships, speaking out in lectures and tutorials, requesting information, joining societies, attending social functions, having social contact outside class hours, establishing a peer support network and being assertive. Additionally, many students with AS experience difficulty with executive functioning skills. This impacts on their ability to organise and manage their time (and thus meet assignment deadlines), prioritise activities, structure and plan assignments, and set goals. Students may also experience issues with the sensory environment of college; this can be due to poor sensory processing and regulation. They may experience poor concentration within the lecture or tutorial room, become easily distracted by noise and the individuals within the environment and may result in the student becoming reluctant to attend lectures and tutorials. Students may also experience difficulty with orientation of the college campus and facilities and some struggle to negotiate the systems within college, such as; the library process and the administrative policies. Some of these issues can escalate into feelings of being overwhelmed and the inability to cope with these demands. Students with AS tend to experience higher levels of stress and Gleeson C., Quinn S., & Nolan C. Unilink, University of Dublin, Trinity College. Page |8 anxiety compared to their peers within this environment (Adreon & Durocher, 2007). Mental health difficulties in individuals with AS have been attributed to social alienation; yet they have been found to want and benefit from social support (Jones, Zahl, & Huws, 2001). Third Level Support for Students with Asperger’s Syndrome The support needs required for individuals with Asperger’s Syndrome as they enter into third level education are complex and highly idiosyncratic and are at odds with the student’s apparent capability (MacLeod & Green, 2009). The importance of supports for individuals with AS in primary and secondary level education are well recognised but there appears to be less research and services at third level education (Clark, 2003). In order to cater for the needs of these students as they enter into a different and complicated environment of third level, we need to be ready and willing to respond effectively to the needs of these students with Asperger’s Syndrome. Trinity College Dublin offers students with mental health difficulties a unique occupational therapy service, known as Unilink. Unilink is a collaboration between the Discipline of Occupational Therapy and the Disability Service in Trinity College. The Unilink Service was established in 2004 by Clodagh Nolan, a lecturer in the Discipline of Occupational Therapy in response to a need to provide practical support for students with mental health difficulties; such as Depression, Schizophrenia, Asperger’s Syndrome (AS) and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in managing the day-to-day things that students need and want to do both academically and socially, in order to achieve their full potential and complete their studies and go on to become productive members of society (Nolan, Quinn & Gleeson, 2009). Since 2006 a designated occupational therapist was employed to work specifically with students with AS in order to support their unique needs and to develop a specialist AS strand within the Unilink Service that caters specifically for these students. Gleeson C., Quinn S., & Nolan C. Unilink, University of Dublin, Trinity College. Page |9 Although services for people with disabilities at third level have improved in recent years, there remains a long way to go before the types of comprehensive support required by people with AS are in place within the tertiary sector. ASPIRE, the Irish Asperger’s Syndrome Association highlight in their consultation to the National Strategy for Higher Education (ASPIRE, 2009) that the Unilink Service is very useful in supporting students with Asperger’s Syndrome, however they indicate that this support should be provided and made available by all third level institutions in Ireland. Profile of Student’s with Asperger’s Syndrome Utilising the Unilink Service This section of the paper outlines the number of students with Asperger’s Syndrome both nationally and locally within the Unilink Service. This table below taken and adapted by the Higher Education Authority (HEA) (HEA, 2010) highlights the number of students receiving funding for a diagnosis of Autistic Spectrum Disorder over the past three years. The table identifies the high increase in the number of students with Asperger’s Syndrome utilising available funding in third level education. Table 1. Total number of beneficiaries of the Fund for Students with Disabilities 2006 2008 in Irish Higher Education Institutions Year 2006-07 2007-08 2008-09 Number of Students with Autistic Spectrum Disorder 6 14 42 Mirroring this general increase the number of students attending Unilink, with a diagnosis of Asperger’s Syndrome, has grown steadily over the past four years and reflects the higher prevalence of AS in males. Gleeson C., Quinn S., & Nolan C. Unilink, University of Dublin, Trinity College. P a g e | 10 Year Males Females Total 2009-10 19 1 20 2008-09 13 1 14 2007-08 5 0 5 2006-07 3 0 3 Table 2: Number of students with Asperger’s Syndrome in TCD utilising the Unilink Service by gender and across time Many students with AS utilising the Unilink Service have dual diagnoses meaning that they not only experience difficulties associated with their diagnosis of AS but also additional difficulties due to other mental health disorders, such as ADHD, depression etc. Specifically, no students had diagnoses in addition to that of AS in 2006-08, however, five students with AS had a dual diagnosis in 2008-09 and this rose to seven students in 2009-10. With regards to the subject areas studied by students with AS, Unilink has found that in the last two years more students with AS have emerged from the Faculty of Engineering, Science and Mathematics than other faculties. This may be due to the appeal of the factbased math and science courses on offer in this Faculty. Year Faculty of Arts, Humanities & Social Science 2009-10 2008-09 2007-08 2006-07 8 5 4 3 Faculty of Engineering, Mathematics & Science 12 9 1 0 Faculty of Health Sciences 0 0 0 0 Table 3: TCD Faculty distribution of students with Asperger’s Syndrome utilising Unilink Gleeson C., Quinn S., & Nolan C. Unilink, University of Dublin, Trinity College. P a g e | 11 In 2009-10, the number of students in Junior Freshman (first year) utilising the Unilink Service increased considerably. While this may be attributed to the rising numbers of students with disabilities attending third level and a general increase in individuals being identified with AS, a procedural change to the referral process may also contribute to this increase. Following the high number of senior freshman (second year students) who began using Unilink in 2008 (an eight-fold increase on the previous year, see Figure 1) a decision was made by the Disability Service and Unilink to provide students with Unilink, occupational therapy support from the outset of their university career, so referrals are now made on entry to college to Unilink. Figure 1: The number of students with AS utilising Unilink according to college standing 9 Number of Students 8 7 Junior Freshman 6 Senior Freshman 5 Junior Sophister 4 Senior Sophister 3 Postgraduate 2 1 0 2009-10 2008-09 2007-08 2006-07 As occupational therapists the Unilink Service is concerned with the student’s engagement and performance in college occupations (such as studying and socialising) and their capacity to perform their student role. Using a myriad of activities and strategies the occupational therapist within Unilink will support the student with AS to set and attain occupational related goals. Goals students have set in the past have included the development of academic, time management and organisational skills; anxiety and illness management; life style design and progress in the area of social relationships. Intervention strategies are Gleeson C., Quinn S., & Nolan C. Unilink, University of Dublin, Trinity College. P a g e | 12 typically practical, for example, preparing timetables with students so that they know what to do, where and when; role-playing social situations; and using writing techniques to overcome procrastination, and are employed according to need. To illustrate the type of support Unilink may offer students with AS, an example of a student’s story is shared below. One Student’s Journey through the Unilink Service Student: Billy is a 21 year old student studying in college. At 18 years old Billy made the transition from secondary school to university. Study: Second Year; Faculty of Engineering, Mathematics and Science Reason for Referral: Referred for Unilink assessment and support in managing his role as a student. Background Information gleaned from the Initial Interview: Billy attended his first Unilink session after being unsuccessful in meeting the demands of his college course. He did not have his course assignments and projects handed in on time and also found it difficult to prepare for exams and as a result failed his end of year exams. Billy was not attending 60% of his lectures and tutorial classes. Billy also really wanted to fit in and wanted to be involved in college life but not in the way he had done in his previous year, as he spent a lot of time attending society events. Areas identified/Goals: 1. To meet course demands by submitting essays and assignments on time. 2. To develop organisational and time management skills to better manage his role as a student. 3. To develop balanced routines that incorporate academic and social occupations. 4. To develop skills in essay writing and exam technique. Gleeson C., Quinn S., & Nolan C. Unilink, University of Dublin, Trinity College. P a g e | 13 Intervention strategies/work done with Joe: 1. Established healthy and balanced routines through the use and development of timetables to incorporate study time, social aspects of his life and leisure pursuits. 2. Billy learned how to prioritise different occupations, set goals and achieve the goals established. 3. Practical support provided to help Billy to start assignments; support provided for researching, planning and structuring essays/assignment projects. 4. Monitored Billy’s involvement and engagement in societies. 5. Billy learnt and practiced deep breathing exercises that helped manage his stress and anxiety levels. 6. To attend all lecture and tutorial classes. Outcome: 1. Billy submitted all assignments and projects on time in comparison to not submitting any assignments the previous year. 2. Billy sat all his exams and successfully passed the year. 3. Billy is now better able to manage the different occupations that he must do throughout the day; both academic and social. 4. Billy developed and has implemented all organisational and time management skills into his daily routine. 5. Billy’s attendance improved dramatically and attended all lectures and tutorials in his repeat year. 6. Billy is continuing to receive on-going input from the AS strand of the Unilink Service. Gleeson C., Quinn S., & Nolan C. Unilink, University of Dublin, Trinity College. P a g e | 14 Student-Outcomes within the Unilink Service While students with AS may share common diagnostic traits how these impact on individual students vary. Central to Unilink’s success in working with these students is a recognition of the individuality of each student’s case – students’ concerns, expectation of college, needs and desires differ as a function of many factors including the student’s own abilities and strengths, their past experiences in education, their support network, and their living conditions. Similarly, a student’s progress through third level may be measured in a variety of ways – quantitatively, by means of end of year scores and progression; qualitatively, by asking students about the quality of their life in college. In Table 4 we present student outcomes measured according to their academic progression within the university. Year Progressed-rose with year Failed and Repeated Graduates Supported withdrawal from college 2009-10 Unknown at present Unknown at present Unknown at present Unknown at present 2008-09 11 0 0 3 2007-08 4 1 1 0 2006-07 2 1 0 0 Table 4: Students’ progression in university according to year Gleeson C., Quinn S., & Nolan C. Unilink, University of Dublin, Trinity College. P a g e | 15 Future directions for the Asperger’s Syndrome strand of the Unilink Service As an evidence-based service Unilink engages in ongoing evaluation. Life balance and leisure engagement have emerged as an identified need for this group of students. Consequently, a group intervention focusing on leisure engagement will be piloted in 201011. This group will examine and explore the past and present leisure interests and occupations of individuals with Asperger’s Syndrome in third level education and to explore the opportunities for increasing the scope for meaningful leisure engagement and participation within the university environment using a collaborative group approach with the students. Conclusion The International Classification of Functioning identifies participation in occupations as the ultimate outcome for individuals with disabilities (WHO, 2001) and similarly engagement in meaningful occupations to support participation within the context of the client is the aim and focus of all occupational therapy intervention (AOTA, 2008). Given the nature of the third level social, institutional and physical environment and the typical characteristics / impairments of individuals with Asperger’s Syndrome, many are likely to face certain challenges when coming to college. Tailor-made support services that understand the particular and individual difficulties of students with Asperger’s Syndrome are required to facilitate students’ participation in all aspects of college life, and enable students realise their abilities so that they can develop both personally and academically. Gleeson C., Quinn S., & Nolan C. Unilink, University of Dublin, Trinity College. P a g e | 16 References Adreon, D., & Durocher, J. (2007). Evaluating the college transition needs of individuals with high-functioning Autism Spectrum Disorders. Intervention in School and Clinic, 42(5), 271279. AHEAD. (2008). Participation rates of students with disabilities in higher education 2005/6. Dublin: AHEAD Publication Press. American Occupational Therapy Association. (2008). Occupational therapy practice framework: domain and process (2nd ed.). American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 62(6), 625-683. American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. Asperger, H. (1944). Autistic psychopathy in childhood. In U. Frith (1991), Autism and Asperger Syndrome. UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-38608-X. ASPIRE – the Asperger’s Syndrome Association of Ireland. (2009). What is Asperger’s Syndrome? www.aspire-irl.org. Retrieved 21st May 2010. ASPIRE- the Asperger’s Syndrome Association of Ireland. (2009). Consultation to the National Strategy for Higher Education Submission on behalf of Aspire - The Asperger Syndrome Association of Ireland- http://www.hea.ie/files/files/file/DoE/Aspire%20%20Asperger%20Syndrome%20Association%20of%20Ireland%20%205.pdf. Retrieved on 20th May 2010. Gleeson C., Quinn S., & Nolan C. Unilink, University of Dublin, Trinity College. P a g e | 17 Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Stone, V., & Rutherford, M. (1999). A mathematician, a physicist and a computer scientist with Asperger Syndrome: Performance on folk psychology and folk physics tests. Neurocase, 5, 475-483. Baskin, J.H., Sperber, M., & Price, B.H. (2006). Asperger Syndrome revisited. Rev Neurol, 3(1): 1-7. Clark, T. (2003). Post 16 provision for those with autistic spectrum conditions: Some implications of the Special Educational Needs and Disability Act 2001 and the Special Eduucational Needs Code of Practice for Schools. Support for Learning. 18(40, 184-9. Frith, U. (1991). Autism and Asperger Syndrome. UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521-38608-X. Fujikawa, H., Kobayashi, R., Koga, Y., & Murata, T. (1987). A Case of Asperger’s Syndrome in a nineteen-year-old who showed psychotic breakdown with depressive state and attempted suicide after university. Japanese Society for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 28(4), 217225. Government of Ireland. (1997). Universities Act. Dublin: Stationary Office. Government of Ireland. (2000). Equal Status Act. Dublin: Stationary Office. Government of Ireland. (2005). Disability Act. Dublin: Stationary Office. Gleeson C., Quinn S., & Nolan C. Unilink, University of Dublin, Trinity College. P a g e | 18 Jones, R.S.P., Zahl, A., & Huws J.C. (2001). First Hand accounts of emotional experiences in autism: A qualitative analysis. Disability and Society. 16(3), 393-412. Lyons, V. & Fitzgerald, M. (2005). Early Memory and Autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35, 5, 683. Madaus, J.W. (2005). Navigating the college transition maze: A guide for students with learning disabilities. Teaching Exceptional Children, 37(3), 32-37. MacLeod, A., & Green, S. (2009). Beyond the Books: case study of a collaborative and hiolistioc support model for university students with Asperger’s Syndrome. Studies in Higher Education. McPartland, J., & Klin, A. (2006). Asperger's Syndrome. Adolescent Medical Clinic. 17(3), 771–88. Morrison, J.Q., Sansoti, F.J., & Hadley, W.M. (2009). Parent perceptions of the anticipated needs and expectations for support for their college bound students with Asperger’s Syndrome. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 22(2), 78-87. Nolan, C., Quinn, S., & Gleeson, C. (2009). Report on the Unilink Service – An Occupational Therapy Mental Health Initiative. Five years on 2004 – 2009. Dublin: University of Dublin, Trinity College. Walker A., & Fitzgerald, M. (2006). Unstoppable Brilliance. Dublin Liberties Press Gleeson C., Quinn S., & Nolan C. Unilink, University of Dublin, Trinity College. P a g e | 19 Whitehouse, A.J., Durkin, K., Jaquet, E., & Ziatus, K. (2009). Friendship, loneliness and depression in adolescents with Asperger’s Syndrome. Journal of Adolescence, 32(2), 309322. Wing, L. & Gould, J. (1979). Severe impairments of social interaction and associated abnormalities in children epidemiology and classification. Journal of Autism and Childhood Schizophrenia, 9, 11-29. Wing, L., & Porter, D. (2002). The epidemiology of autistic spectrm disorders: Is the prevalence rising? Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 8(3), 151-61 World Health Organisation. (2001). International classification of functioning, disability and health: ICF (Short Version Ed.). Geneva: World Health Organisation. World Health Organization. (2006). Pervasive developmental disorders. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (10th (ICD-10) ed. Geneva: World Health Organization. Gleeson C., Quinn S., & Nolan C. Unilink, University of Dublin, Trinity College.