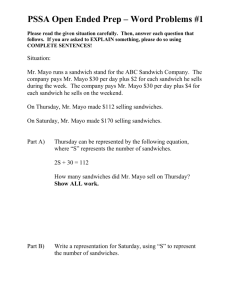

Civil War in Mayo

advertisement