Article Review

advertisement

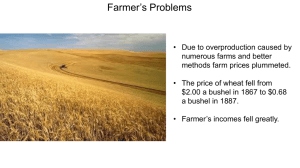

Article Review Student name: Myrto Lada ID:1563200800115 Reference: Savage, R. (2010) “Populist elements in contemporary American political discourse”. The Sociological Review 58(52): 167-188. Abstract: Granted that it would be absurd to characterize Obama as a populist president, this paper proceeds from Ernesto Laclau’s conception of populism as consisting of ‘the formation of an internal antagonistic frontier separating the “people” from power’ and ‘an equivalential articulation of demands making the emergence of the “people” possible’ (2005:74). In the 2008 election, Obama was able to articulate a series of empty signifi ers, found in such slogans as ‘Yes We Can,’ which came to represent a new collective identity of the ‘people’, thus constituting an instance of populism par excellence. As support for this theory of populism and its implications for contemporary American political discourse, this paper deconstructs the previously held functionalist assumptions and modernization theories – especially those propagated within Latin American case studies – that consign populism to a developmental stage in the capitalist mode of production or a historical outcome of underdeveloped democratic institutions in order to imagine a new science of rhetoric capable of analysing the synecdochical, metaphorical, and metonymical components (Laclau, 2005) in the discursive construction of ‘the American people’. The specific journal article argues that populism as a unified discursive socio-political phenomenon is to be found in both Latin-American and Western European cases no matter of the Capitalist mode, developmental stage or degree of economic production. More specifically, Ritchie Savage suggests that Laclau’s model of populism can unite the various divergent instances of populism under a unified theoretical framework and analyze them accordingly. In that spectrum, it is argued that not only the contemporary rhetoric of Barack Obama contains populist elements but also that populism there functions and proliferates itself the same way as in seemingly non-comparable populist cases of Latin-America. Laclau’s discursive model of populism basically perceives populism as a discourse with linguistic and relational attributes that is inextricably related to Lacan’s symbolic order of society. That is, the symbolic order is continuously disrupted by dislocations (antagonisms and crises within society) and the instability of Saussurean signification between signifiers and signifieds. At that point, populism functions by giving meaning to empty signifiers (such as ‘people’) and thus ‘restoring’ the symbolic order of society by forming political identities of belonging to a social totality or group. The signifying totality, in turn, needs to exclude one of its differentiated elements so as to define itself. However, when one of those elements comes to signify totality, a hegemonic identity occurs. In taking into consideration the various definitions provided by scholars throughout, Savage suggests that the one of Laclau’s seems to be the most applicable one since it transcends regional, social and temporal variables and sets the ground for a wider systematic schema of analyzing populist phenomena and that of Obama’s populism in particular. More specifically, the author’s argumentation is further supported by presenting and critiquing the various models that try to explain the emergence of populism in both Latin-America and Unites states as failing attempts to grasp the phenomenon of populism in its totality. Moreover, according to the writer, the affiliations shared between Western European ‘New Populism’ and Latin –America populism in promoting the same anti-system, centralized and authoritarian structures, further suggest the above mentioned argument that populism cannot be fully explained within economic and historical frameworks alone. Finally, Obama’s election is illustrated as an instance of populism following Laclau’s model of analysis accordingly. In Obama’s case, it is claimed that the symbolic order of society was disrupted by the economic crisis along with people’s disenchantment with the up to then Republican administration. This new state of affairs had left behind unanswered popular demands that were linked to Laclau’s “equivalential chain of demands” and finally filled in the system of abstract signification by providing with meaning and identity the signifier of the ‘American people’. This article is particularly enlightening in raising awareness of how populism has been perceived so far across cases. We as readers trace throughout it the thesis that it is insufficient to analyze populism only in terms of historical reasons and developmental modes of capitalism alone; One should instead apply Laclau’s model of analysis so as to draw parallels between strikingly divergent instances of populism and understand its structural pattern. This suggestion is convincingly supported by two theoretical assumptions. The first assumption in support of this thesis is that despite the various populist instances, populism has always the same discursive structure applied to all instances as well as that Laclau’s unifying model can indeed always provide the larger theoretical framework. The second assumption which is expressed is that the literature review of the various models of analysis in the United States, Latin-America and Western Europe reveals itself the failure of a unified conception of populism. In justifying these assumptions Savage extensively discusses Laclau’s model and provides us with a historical overview of the various analyses. Savage uses her material with awareness and cautiousness. She follows a logical order in presenting them that bridges the gaps among the various theories and builds up a solid argumentative sequence. She is also critical on omissions and reliability of each theory. However, some Lacanian terms used in the article miss a proper definition. In terms of validity though, one could argue that the specific article is not too strong. Savage provides us with an extensive literary analysis of her topic accompanied by historical accounts on populism which altogether are thoroughly discussed. However, their interpretation is based mostly on theoretical grounds and on the author’s personal observation. That is to say with the exception of the empirical evidence provided by other scholars, the specific article lacks a solid methodology used of its own. As far as our own research project is concerned, the specific article’s contribution to our topic is of high importance. First of all, it extensively discusses the phenomenon of populism’s emergence in America which is of direct relevance to the formation of the collective identity in political discourses studied by our research project. Moreover, it offers indispensable insight on how populism systematically manipulates the sense of totality by filling abstract significations with meaning and it explains, thus, how populism disseminates itself across cultures. In addition, this journal article is directly associated to our study by presenting Obama’s campaign slogans such as ‘Yes we can’, ‘Hope’, ‘We Are the People We’ve Been Waiting For’ as genuine instances of populism. Finally, the discussed article, as a whole, is judged to be thorough, clear and convincing enough in discussing populism through multiple perspectives. However, there is yet one perspective which has been left undiscussed and needs to be taken into account; the psychological one. In assuming that populism is characterized by a structuralist pattern that is applicable to all cases its psychological dimension is neglected. In other words, what is argued here for further discussion is that people cannot be perceived as passive receivers of populist significations. More or less they encompass different views, attitudes and thoughts that vary their response even to the same instance of populism or ideology and thus affect the whole approach to populism as such.