Document 6892202

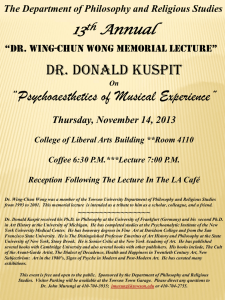

advertisement

We would like to thank the referees for their very helpful comments. Below we have separated these out into separate issues to be addressed, and have included our responses and any changes in the text that are localized and can be usefully reproduced here. Comments: Very few students likely plan to major in philosophy coming into their first philosophy class (in the U.S. it is less than 1% of students entering college), so finding that fewer women students report wanting to major in the first-lecture survey does not mean that experiences in first philosophy courses could not drastically influence the number and proportion of women majors. That is, even if only 1/3 of students entering college interested in taking more than one philosophy course in college are women, if the majority of students making decisions about whether or not to major in philosophy do so only after taking philosophy (and other) courses, then those courses will be crucial for determining how many students, and how many women, decide to major in philosophy. The referee makes two important suggestions here. The first is that there would, or could, have been a large set of students who were unsure what they were going to major in, and it could be that unsure women were less likely to decide to major in philosophy than unsure men, , on the basis of their experiences of first year philosophy. The second is that even if small percentages of women enter college are interested in taking more philosophy, if they then make choices based on their experiences of philosophy then this will determine how likely women are to decide to major in philosophy and also how likely they are to decide to take additional philosophy courses if they choose not to major in philosophy. We have attempted to clarify this, since it is an important point, by adding in the following: Overall, the mean response for female students with regard to intention to major, ability to do philosophy, comfort in class, and interest in philosophy did not change significantly as compared to the mean response for male students on these issues. One might wonder if the absence of a classroom effect is the result of tracking students’ responses to the question of whether they are intending to major in philosophy. The worry here is that plausibly a small proportion of students have made a decision about their major, and fewer still have decided to major in philosophy. Thus there is a large pool of students who are unsure as to their major. Perhaps, then, women’s experiences through the course will drastically influence how likely it is that they are to major as compared to men’s experiences through the course in one of two senses: (1) women who are unsure at the beginning of the course are more likely to decide not to major by the end of the course as compared to men; (2) men who are unsure at the beginning of the course are more likely to decide to major by the end of the course as compared to women. The same worry could be raised in the context of male and female students reporting whether or not they intend to take further philosophy subjects if they are not intending to major. Perhaps many students are initially unsure, and female students are more likely to become sure that they will not take further philosophy units than male students as a result of their classroom experiences. The present study does not vindicate either of the two hypotheses outlined in the previous paragraph. We tracked the mean responses to each question on a Likert scale for both men and women across time. What we saw was that the average response for women across the course did not change significantly more than the average response for men. If more women who were unsure at the beginning of the course were deciding not to major in philosophy than men, we would expect to see a lot more movement around the mean. In particular, the mean for women should have dropped by a higher degree than the mean for men. This did not happen. Similarly, if more men who were unsure at the beginning of the course were deciding to major in philosophy than women, we would expect to see the mean for men rise higher than the mean for women. Again, that was not supported by the results: the mean response for men and the mean response for women changed to the same degree across the course, suggesting that women were not disproportionately put off philosophy as compared to men due to their experiences in the course. More generally, we found no evidence that women’s experiences through a philosophy course were more likely to determine their intention to major as compared to men’s experiences. The same is true for those students who were unsure whether they would take additional philosophy units: we find no significant difference in the movement around the mean for women as compared to men with respect to whether they will take additional philosophy subjects. Again, if women who were unsure at the beginning of the course were more likely to be put off by the end of the course than men, then this should show in the means. While altering the gender schema for philosophy for students entering college is an important intervention to increase the number of women who major, interventions in the college classroom (including ones to alter the gender schema) are still likely to be the most significant. The authors suggest this idea in the conclusion but put it only in terms of intervening in college classes to shape precollege perceptions of philosophy. They do not emphasize sufficiently that the college class can also shape perceptions (especially for those whose pre-college ones were weak) and counteract them. We agree with the referee’s point here that interventions within the classroom are still likely to make a large difference to, for instance, intention to major in philosophy. Accordingly, we have added in an extra paragraph in the conclusion to emphasise this point. The paragraph reads: It is worth noting, however, that while challenging gender schemas for students entering university is an important intervention to increase the number of women who major in philosophy, interventions within the classroom (including ones to alter the gender schema) are still likely to be the most significant. That’s because it may well be that many students do not decide whether to major (and what to major in) until the end of their first year. Accordingly, throughout this uncertain period, there is a great deal of scope for challenging gender schemas surrounding philosophy with the aim of increasing female representation in undergraduate philosophy. The results of the authors’ study are important and interesting. However, it is hard to know the extent to which the results generalize outside of Australia, and especially to the U.S., in part because some of the trends discovered in the first-lecture survey suggest that students already have enough knowledge about what philosophy is to have opinions about their interest, confidence, etc. in philosophy. We agree that it is difficult to know the extent to which any such study can be generalized. We have expanded on what we said to include the following: Finally, because our study was carried out in [Blinded], Australia, the results possess a limited ecological validity due to cultural idiosyncrasies that are no doubt present but difficult to control for. Care must therefore be taken in extrapolating our conclusions outward to e.g. North America or the United Kingdom. It is our view that the value of such studies lies in the gradual accretion of data. We do not suppose that the results of this survey can simply be extrapolated to other countries; rather, our hope is that similar work will take place in other locations and that jointly that work will shed light on this issue. This study is but one piece of that overall picture; but, we think, an important one. I suspect that most students in the U.S., where philosophy is not taught in high school, do not have enough understanding of the field to have opinions about it one way or the other (e.g., about Qs 4-5 and 7-10, and especially 11-12), or have uninformed opinions that would be shaped more significantly by their experience in their first college philosophy class. And I’m not sure whether the same effects would be found in North America, the U.K., and elsewhere, in any case. The authors should discuss this issue more fully and perhaps provide more information about the Australian system, both pre-college (e.g., have most students taken philosophy?) and in college (e.g., is philosophy possible as a double major or a minor, how many courses can students take outside of their major, etc.?). Most readers of the paper are likely to work in U.S. colleges, so this information is important. We have added in the following material to address this issue. However, in order to get a better sense of the extent to which the Australian University and preUniversity system is similar to, and different from, the US and UK it is worth making some general comments. First, it is notable that although students typically had opinions about philosophy as a discipline when surveyed in the first lecture, very few of those students would have encountered philosophy prior to University. Very few schools in Australia offer philosophy as a subject. So an overwhelming majority of students must have formed opinions about philosophy without having ever having been exposed to it. (In this we expect Australia is not dissimilar to the UK and US). Second, it is worth saying something brief about the structure of Australian degrees (most relevantly Arts degrees) since appreciating whether or not students are inclined to want to take philosophy units outside of their non-philosophy major is sensitive to how flexible the degree structure is, and to how many non-major units students are able to take. At [blinded] students can take a double major, a major, or a minor in subjects such as philosophy. Within the Faculty of Arts, students can take as many as 6 first year units outside their major subject, and as many as 10 second and third year (combined) units outside their major subject. Thus in all students can take 16 units that do not fall within their major subject. To put that in perspective, students must complete 6 second and third year (combined) units within their major subject leaving the remaining 10 to be taken from other disciplines. There is, therefore, substantial flexibility for students to enroll in philosophy courses even if they are not intending to major in philosophy. On pp. 8-15, the authors draw some of their most important conclusions regarding the gender differences in interest in majoring in philosophy in the first-lecture survey and then differences (or lack of them) between the two surveys. The techniques they deploy are complex and in some cases seem a bit ad hoc. I am not a statistician, and for a philosophy journal, their techniques are explained as well as can be expected, but it would be useful to have a statistician ensure that these techniques are not problematic. In response to the concerns raised by the referee in the above passage, we have done two things. First, we have had a statistician look over the statistical work within the paper. Second, we have added a footnote on p. 13 (fn. 10) explaining one potential test against which the charge of ad hocness was aimed: the chi-square testing. In that footnote we briefly explain the need for the chi-square test carried out in order to justify its use. Third, we have added an explanation of why it is that we use t-tests when we do, and why we use chi-square tests when we do (pp. 11 and 13 respectively). The tables might also be organized in a way that will make the results clear for non-statisticians. I would have liked to see the mean responses to questions by gender. In order to address this concern about the presentation of the results we have made two changes. First, we have substantially simplified the tables in the main text, so that these can be easily parsed by a non-statistician. We have included the more detailed tables as an appendix, Appendix B, for statistically-minded philosophers to peruse. Second, we have – as the referee suggests – included mean responses for questions by gender where appropriate. On p. 7, the report of numbers of participants might be clarified. At a minimum, the sentence beginning ‘By contrast’ is unclear. This section has been simplified and clarified. It now reads: 596 participants successfully completed the survey at the first lecture. 8 participants were excluded based on being neither male nor female, leaving a final sample of 588. Of these, 230 were male and 357 were female. 252 participants completed the survey at the last lecture. 8 participants were excluded based on being neither male nor female, leaving a final sample of 244. Of these 96 were male and 148 were female. The gender ratio at the first lecture survey was the same as the gender ratio at the last lecture survey (1 man to 1.5 women, see Table 1). So while there was certainly attrition between the first and last lectures, men and women left the course in equal numbers. The most important problem with study, and hence the paper, is that so few students who took the first-lecture survey took the last-lecture survey (roughly 20% if I’m doing the math right). It is impossible to know the opinions of the students who dropped the course, or were skipping it, including the women, or how to consider the opinions of the 20% who stuck with the course, especially if they are not representative of the other 80% of students who did not take the last-lecture survey (it seems about half the students who took the last-lecture survey did not take the first-lecture survey, so that also makes comparisons difficult). For instance, we don’t know if the first- vs last-lecture survey effects discussed in section 3.3 would be different if students who had already left the course offered their responses, some of which might have provided information about why they had left the course. This flaw in the study could not be corrected without further studies. Were future studies to be conducted, it would be useful to correct this issue, at a minimum by tracking (anonymously) which students took both surveys and comparing results for just those students. While the authors do not emphasize this limitation enough (see p. 20 where they seem to brush it aside), they do highlight an important control that needs to be run—i.e., surveys in other subjects to see which gender differences exist for those subjects (both in first- and last-lecture surveys). The referee raises a fair point, and we acknowledge as one of the limitations of the study, the high attrition rate between the first and last lectures. We would like to note, however, that the referee’s suggestion – anonymizing the surveys and pairing first/last lecture surveys with one another in order to carry out statistical testing on the change in attitude for each student across the course – is, in fact, something that we did, though this was perhaps not sufficiently clear in the original manuscript. Accordingly, we have endeavored to clarify on pp. 10–11 that the study was carried out in the fashion recommended by the referee. However, we fully recognize that there is still a problem: the attrition rate across the course has the potential to mask gender differences with respect to shifting attitudes toward philosophy and may explain the null results of this study. That said, it is important to note that the gender ratios were stable across the life of the course (indeed, if anything, slightly more men than women failed to show up to the last lecture). So while it is true that there was a large attrition rate between the two lectures, it is not the case that women left in greater proportions than men. Now, it may still be that men and women are leaving in the same numbers but for different reasons. That is an important concern, and one that cannot be addressed in this study, and must be considered through further testing. At any rate, we feel pressure to say a bit more about this issue and so we have done two things. First, we now report the gender ratios throughout the course in Table 1 on p. 10. Second, in the section where we discuss the limitations of the study, we now take this limitation more seriously (see pp. 25–26 of the new manuscript). In Appendix A, the numbering got messed up for some questions with multiple options. This has been fixed. Finally, if the authors are able to access the recent work by Sarah-Jane Leslie and colleagues on fixed-ability beliefs (FAB), it would be useful to discuss it, since the FAB theory predicts that people have perceptions of certain fields as requiring innate talents (especially philosophy), and that such beliefs lower women’s willingness to enter the field, since innate talent beliefs are gendered. So, it is plausible that women, even before taking college philosophy, would be less interested in majoring if they perceive philosophy as requiring innate talents more than hard work. The authors Q8 is a FAB question but I don’t think they focused on it in the paper. The suggestion that philosophy must alter its perception in the general public, including among students entering college, such that women do not begin their first courses already feeling like they belong in, and can succeed in, philosophy less than men is the most important conclusion of the authors’ paper. It fits well with the FAB theory. We have added discussion of the FAB hypothesis in our section on the various hypotheses (section 1.1) and how our results support a specific version of the hypothesis that postulates a pre-university mechanism, noting that Leslie et al. indicate the possibility of other mechanisms (section 4.1). On p. 22, the authors say that the efforts of one (of 3) instructors to present philosophy as less gendered were unsuccessful in changing students’ perceptions, but it’s not clear that they can make that claim, at least based on the data they report, which is not broken down by instructor. It would be useful if they could compare the results of the surveys across different instructors. This and a subsequent comment made us realize that we had failed to adequately describe the instructors role in the course. We have clarified in 2.1 that three instructors gave lectures in sequence to the entire course. On p. 22 we have clarified that this small intervention was made in lectures that were given to all students. On p. 4, the authors say they test the entire set of hypotheses by comparing pre- vs. post-course survey responses. Even if the number of students who completed both surveys were more consistent, I’m not sure how measuring gender differences in intention to major would succeed at testing all of the hypotheses. Perhaps the authors just mean to say that that measure provides evidence for or against the classroom effect hypotheses relative to the pre-university effects. We have added an additional sentence to clarify that our claim is that if under-representation among intending majors increased during the course, then this would be evidence in favour of at least one member of the set. On p. 5, the authors may want to indicate that the title of the course “Reality, Ethics, and Beauty” (does it have commas?) may not be perceived the same as, or have the same effects as, a course titled “Introduction to Philosophy” which would be the norm at least in U.S. colleges, and may influence which students take the course (more info on why students take this course might be useful). They also should clarify if this was one class with different instructors and the gender of the instructors. (Only later do they mention that there were three instructors.) We have added this information in section 2.1. On pp. 15-16, I am doubtful that the data can rule out the Impractical Subject Hypothesis, because even if there were no gender differences in questions about practicality of philosophy, it may be that women care more about the practicality of the major than men (Q3 might help determine this but it was not analyzed because of scoring problems). Another undiscussed hypothesis is that women and men may care about what sorts of professions the field prepares them for (Q4 is relevant). These points are well-taken, and we have added the reviewer’s point (crediting him/her). Just to be clear though, we don’t claim that the data rules this hypothesis out (or for that matter any of the classroom effect hypotheses). We claim only that we failed to find evidence in support of the hypothesis. On p. 24, I do not understand “but not so for classroom hypotheses.” If the claim is that no controls (with other subjects) are warranted, that seems mistaken. The next sentence is also a bit awkward. We have re-written these sentences to avoid the confusion and awkwardness.