HH 42-15

advertisement

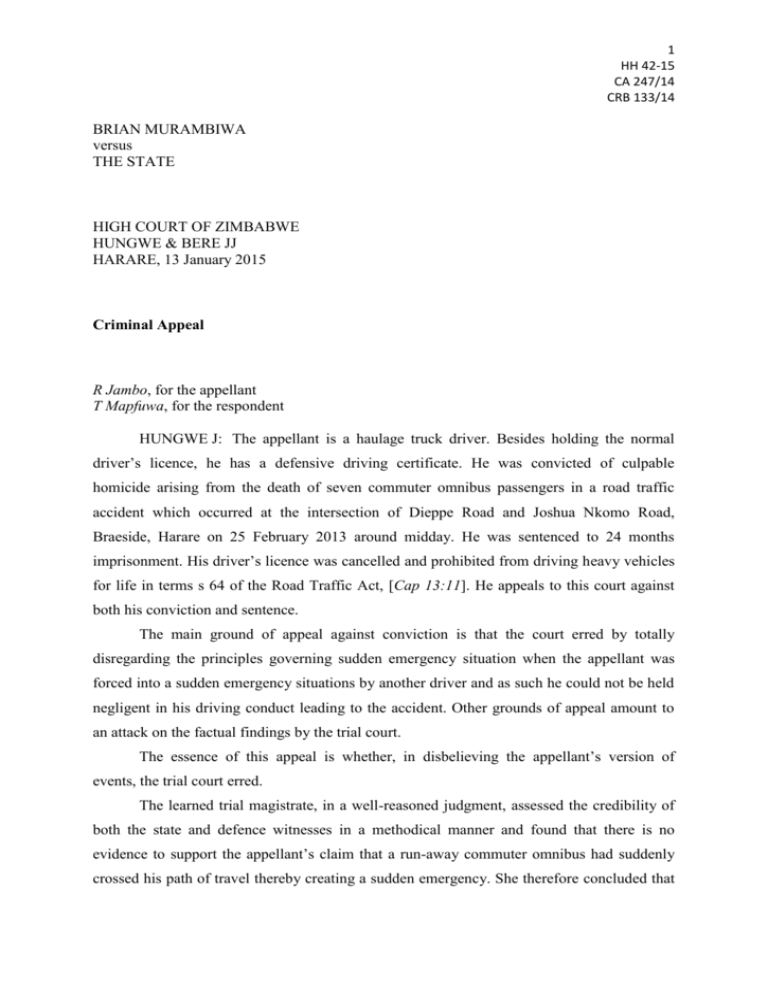

1 HH 42-15 CA 247/14 CRB 133/14 BRIAN MURAMBIWA versus THE STATE HIGH COURT OF ZIMBABWE HUNGWE & BERE JJ HARARE, 13 January 2015 Criminal Appeal R Jambo, for the appellant T Mapfuwa, for the respondent HUNGWE J: The appellant is a haulage truck driver. Besides holding the normal driver’s licence, he has a defensive driving certificate. He was convicted of culpable homicide arising from the death of seven commuter omnibus passengers in a road traffic accident which occurred at the intersection of Dieppe Road and Joshua Nkomo Road, Braeside, Harare on 25 February 2013 around midday. He was sentenced to 24 months imprisonment. His driver’s licence was cancelled and prohibited from driving heavy vehicles for life in terms s 64 of the Road Traffic Act, [Cap 13:11]. He appeals to this court against both his conviction and sentence. The main ground of appeal against conviction is that the court erred by totally disregarding the principles governing sudden emergency situation when the appellant was forced into a sudden emergency situations by another driver and as such he could not be held negligent in his driving conduct leading to the accident. Other grounds of appeal amount to an attack on the factual findings by the trial court. The essence of this appeal is whether, in disbelieving the appellant’s version of events, the trial court erred. The learned trial magistrate, in a well-reasoned judgment, assessed the credibility of both the state and defence witnesses in a methodical manner and found that there is no evidence to support the appellant’s claim that a run-away commuter omnibus had suddenly crossed his path of travel thereby creating a sudden emergency. She therefore concluded that 2 HH 42-15 CA 247/14 CRB 133/14 his claim that there was such an incident in the first place which led to a chain of events leading to the fatal crash was false. It is trite in our law that an appellate court will not interfere with the findings of fact made by a trial court and which are based on the credibility of witnesses. The reason for this approach is that the trial court is better placed to assess the witnesses from its observation, it enjoying the advantage of seeing and hearing them first hand. In S v Isolano 1985 (1) ZLR 62 (SC) DUMBUTSHENA CJ expressed himself thus: “There are many authorities of this court and persuasive authorities from other jurisdictions on the proper approach of an appellate court to the consideration of a decision based on fact. I find the remarks of LORD MACMILLAN in Watt (or Thomas) v Thomas [1947] 1 All ER 582 (HL) at 590 B-D very appropriate in this case. He said: The appellate court had before it only the printed record of the evidence. Were that the whole evidence it might be said that the appellate judges were entitled and qualified to reach their own conclusion upon the case, but it is only part of the evidence. What is lacking is evidence of the demeanour of the witnesses, their candour or their partisanship, and all the incidental elements so difficult to describe which make up the atmosphere of an actual trial. This assistance the trial judge possesses in reaching his conclusion, but it is not available to the appellate court. So far as the case stands on paper, it not infrequently happens that a decision either way may seem equally open. When this is so, and it may be said of the present case, then the decision of the trial judge, who has enjoyed advantages not available to the appellate court, becomes of paramount importance and ought not to be disturbed. This is not an abrogation of the powers of a court of appeal on questions of fact. The judgment of the trial judge on the facts may be demonstrated on the printed evidence to be affected by material inconsistencies and inaccuracies, or he may be shown to have failed to appreciate the weight or bearing of circumstances admitted or proved, or otherwise to have gone completely wrong.” See also Hughes v Graniteside Holdings (Pvt) Ltd S-13-84 (unreported) at 10-14; S v Mlambo 1994 (2) ZLR 410 (S). The trial court interacts with witnesses both visually and orally during trial. It gets the real feel of the events from the description of the witnesses and therefore is inexorably better placed to say which witness’s evidence is to be preferred over the other for the reasons that the court will give. Even where no such reasons are not included in its reasons for judgment, the fact that the trial court commands the first impression on credibility cannot be lightly overturned. Therefore when an appeal court reads the record of proceedings, it must give due weight to the impressions made by the trial court in respect of credibility. 3 HH 42-15 CA 247/14 CRB 133/14 In the present matter, the driver witnesses who would have, in all probability, witnessed the alleged run-away commuter omnibus all testified that they did not see any such vehicle as would have caused the appellant to straddle across into the oncoming motor vehicles’ lane. The appellant’s version of events was contrasted with the evidence of eye witnesses before the court settled on rejecting it. There was a police detail on traffic duty as well as a newspaper vendor. These two would not have an interest in the outcome of an investigation or the trial as they are independent of the events which led to the allegations against the appellant. Both did not confirm the appellant’s claim of the run-away vehicle. The Police Investigating Officer produced a diagram drawn upon indications made by the appellant. In it the appellant indicated to the investigator the point where he claimed he hit into this alleged run-away omnibus. Coincidentally, it is the same point where the two omnibuses involved in the accident collided with the appellant’s heavy vehicle. The facts indicate that the two mini-buses were travelling from the appellant’s opposite side. They were not being pursued by the police as appellant claimed as the reason for the erratic driving conduct of one of them. Given the appellant’s own version, which is highly improbable, the court a quo cannot be criticised for rejecting it. The fact of the matter is that the appellant drove negligently in that he suddenly changed lanes, for no apparent reason, when it was not safe to do so since there was oncoming traffic. He failed to stop or act reasonably when an accident was imminent resulting in him colliding into no less than three motor vehicles. His failure to stop when he straddled into the opposite lane constitutes an act of negligence, more so, if regard is had to the fact that he was approaching a robot-controlled intersection. He was expected to stop, should the driving conditions require him to. His failure to have done so may also indicate that he was driving at a speed excessive in the circumstances. The result of his negligence is that he collided into three motor vehicles which were lawfully using the road and on their correct side of the road. Two of these were commuter omnibuses. From one of them seven people unnecessarily lost their lives. There is on the record sufficient proof of negligence to justify his conviction. This court will not disturb that conviction. As for sentence, we find that the learned trial magistrate properly assessed the degree of negligence in the appellant’s driving conduct and concluded that he was grossly negligent. Appellant approached an intersection driving a heavy vehicle at an excessive speed. He failed to keep his vehicle under proper control; he must have failed to keep a proper look out on the 4 HH 42-15 CA 247/14 CRB 133/14 road and therefore failed to stop or act reasonably when an accident was imminent. In these circumstances we are of the view that the sentence imposed in the court a quo was eminently proper for the degree of negligence displayed by the appellant. See S v Mapeka 2001(2) ZLR 90 (H). We therefore dismiss the appeal in its entirety. __________________________ BERE J agrees. Jambo Legal Practice, appellant’s legal practitioners National Prosecuting Authority, respondent’s legal practitioners