Technical Guide B: Measuring Student Growth & Piloting DDMs

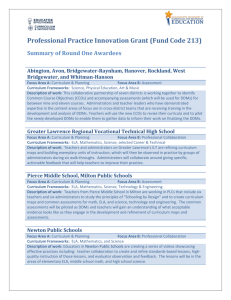

advertisement