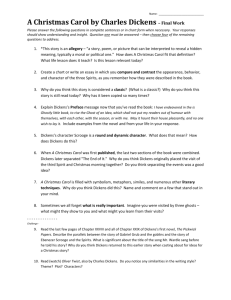

A Christmas Carol- Overview - English-Units 3 & 4-BCH

C

harles Dickens has probably had more influence on the way that we celebrate Christmas today than any single individual in human history...except One.

At the beginning of the Victorian period the celebration of Christmas was in decline. The medieval Christmas traditions, which combined the celebration of the birth of Christ with the ancient Roman festival of Saturnalia (a pagan celebration for the Roman god of agriculture), and the Germanic winter festival of Yule, had come under intense scrutiny by the Puritans under Oliver Cromwell. The

Industrial Revolution, in full swing in Dickens' time, allowed workers little time for the celebration of Christmas.

The romantic revival of Christmas traditions that occurred in Victorian times had other contributors: Prince Albert brought the German custom of decorating the Christmas tree to England, the singing of Christmas carols (which had all but disappeared at the turn of the century) began to thrive again, and the first Christmas card appeared in the 1840s. But it was the Christmas stories of Dickens, particularly his 1843 masterpiece A Christmas Carol , that rekindled the joy of Christmas in Britain and America. Today, after more than 160 years, A Christmas Carol continues to be relevant, sending a message that cuts through the materialistic trappings of the season and gets to the heart and soul of the holidays.

Dickens' describes the holidays as "a good time: a kind, forgiving, charitable, pleasant time: the only time I know of in the long calendar of the year, when men and women seem by one consent to open their shutup hearts freely, and to think of other people below them as if they really were fellow-passengers to the grave, and not another race of creatures bound on other journeys." This was what Dickens described for the rest of his life as the "Carol Philosophy".

Dickens' name had become so synonymous with Christmas that on hearing of his death in 1870 a little costermonger's girl in London asked,

"Mr. Dickens dead? Then will Father Christmas die too?"

Tiny Tim's Ailment

In the December 1992 issue of the American Journal of Diseases of

Children Dr. Donald Lewis, an assistant professor of pediatrics and neurology at the Medical College of Hampton Roads in Norfolk, Virginia, theorized that Tiny Tim, Bob Cratchit's ailing son in Charles Dickens' classic A Christmas Carol, suffered from a kidney disease that made his blood too acidic.

Dr. Lewis studied the symptoms of Tim's disease in the original manuscript of the 1843 classic. The disease, distal renal tubular acidosis

(type I), was not recognized until the early 20th century but therapies to treat its symptoms were available in Dickens' time.

Dr. Lewis explained that Tim's case, left untreated due to the poverty of the Cratchit household, would produce the symptoms alluded to in the novel.

According to the Ghost of Christmas Present, Tim would die within a year.

The fact that he did not die, due to Scrooge's new-found generosity, means that the disease was treatable with proper medical care. Dr. Lewis consulted medical textbooks of the mid 1800's and found that Tim's symptoms would have been treated with alkaline solutions which would counteract the excess acid in his blood and recovery would be rapid.

While other possibilities exist, Dr. Lewis feels that the treatable kidney disorder best fits "the hopeful spirit of the story."

Source - AP Science Writer Malcolm Ritter-1992

Ebenezer Scrooge

In the opening stave of A Christmas Carol Dickens describes Ebenezer

Scrooge:

Oh! But he was a tight-fisted hand at the grind- stone, Scrooge! a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous, old sinner!

Hard and sharp as flint, from which no steel had ever struck out generous fire; secret, and self-contained, and solitary as an oyster.

The cold within him froze his old features, nipped his pointed nose, shriveled his cheek, stiffened his gait; made his eyes red, his thin lips blue and spoke out shrewdly in his grating voice. A frosty rime was on his head, and on his eyebrows, and his wiry chin. He carried his own low temperature always about with him; he iced his office in the dogdays; and didn't thaw it one degree at Christmas.

External heat and cold had little influence on Scrooge. No warmth could warm, no wintry weather chill him. No wind that blew was bitterer than he, no falling snow was more intent upon its purpose, no pelting rain less open to entreaty. Foul weather didn't know where to have him. The heaviest rain, and snow, and hail, and sleet, could boast of the advantage over him in only one respect. They often "came down" handsomely, and

Scrooge never did.

Nobody ever stopped him in the street to say, with gladsome looks, "My dear Scrooge, how are you? When will you come to see me?" No beggars implored him to bestow a trifle, no children asked him what it was o'clock, no man or woman ever once in all his life inquired the way to such and such a place, of Scrooge. Even the blind men's dogs appeared to know him; and when they saw him coming on, would tug their owners into doorways and up courts; and then would wag their tails as though they said, "No eye at all is better than an evil eye, dark master!"

But what did Scrooge care? It was the very thing he liked.

The Many Faces of Ebenezer

Scrooge

The Internet Movie

Database lists more than 100 actors who have portrayed the famous Dickensian miser. Some of the best are pictured here.

A Good Humoured Christmas Chapter

Excerpt from The Pickwick Papers Chapter 28

We write these words now, many miles distant from the spot at which, year after year, we met on that day, a merry and joyous circle. Many of the hearts that throbbed so gaily then, have ceased to beat; many of the looks that shone so brightly then, have ceased to glow; the hands we grasped, have grown cold; the eyes we sought, have hid their lustre in the grave; and yet the old house, the room, the merry voices and smiling faces, the jest, the laugh, the most minute and trivial circumstances connected with those happy meetings, crowd upon our mind at each recurrence of the season, as if the last assemblage had been but yesterday!

Happy, happy Christmas, that can win us back to the delusions of our childish days; that can recall to the old man the pleasures of his youth; that can transport the sailor and the traveller, thousands of miles away, back to his own fireside and his quiet home!

A Christmas Carol

Dickens' cherished little Christmas story, the best loved and most read of all of his books, began life as the result of the author's desperate need of

money. In the fall of 1843 Dickens and his wife

Kate were expecting their fifth child. Requests for money from his family, a large mortgage on his Devonshire Terrace home, and lagging sales from the monthly installments of Martin Chuzzlewit , had left Dickens seriously short of cash.

The seeds for the story that became A Christmas Carol were planted in

Dickens' mind during a trip to Manchester to deliver a speech in support the Athenaeum, which provided adult education for the manufacturing workers there. Thoughts of education as a remedy for crime and poverty, along with scenes he had recently witnessed at the Field Lane Ragged

School , caused Dickens to resolve to "strike a sledge hammer blow" for the poor.

As the idea for the story took shape and the writing began in earnest,

Dickens became engrossed in the book. He wrote that as the tale unfolded he "wept and laughed, and wept again' and that he 'walked about the black streets of London fifteen or twenty miles many a night when all sober folks had gone to bed."

At odds with his publishers, Dickens paid for the production cost of the book himself and insisted on a lavish design that included a gold-stamped cover and four hand-colored etchings. He also set the price at 5 shillings so that the book would be affordable to nearly everyone.

The book was published during the week before Christmas 1843 and was an instant sensation but, due to the high production costs, Dickens' earning from the sales were lower than expected. In addition to the disappointing profit from the book Dickens was enraged that the work was instantly the victim of pirated editions. Copyright laws in England were often loosely enforced and a complete lack of international copyright law had been Dickens' theme during his trip to America the year before.

He ended up spending more money fighting pirated editions of the book than he was making from the book itself.

Despite these early financial difficulties, Dickens' Christmas tale of human redemption has endured beyond even Dickens' own vivid imagination. It was a favorite during Dickens' public readings of his works late in his lifetime and is known today primarily due to the dozens of film versions and dramatizations which continue to be produced every year.

Preface to the Original Edition

A Christmas Carol

I have endeavoured in this Ghostly little book, to raise the Ghost of an

Idea, which shall not put my readers out of humour with themselves, with each other, with the season, or with me. May it haunt their houses pleasantly, and no one wish to lay it.

Their faithful Friend and Servant,

C. D.

December, 1843.

A Darker Christmas

Christmas feasting, merrymaking, and good cheer in Dickens' earlier novels gives way to a darker, more reflective Christmas in the later novels. It is during the Christmas season that Pip encounters the escaped convict, Magwitch, on the marshes in the beginning of Great Expectations .

In Dickens' last, and uncompleted, novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood , his description of Christmas Eve in Cloisterham is both somber and reflective, and the trappings of the season seem a hollow and thin veneer:

Christmas Eve in Cloisterham

A few strange faces in the streets; a few other faces, half strange and half familiar, once the faces of Cloisterham children, now the faces of men and women who come back from the outer world at long intervals to find the city wonderfully shrunken in size, as if it had not washed by any means well in the meanwhile. To these, the striking of the Cathedral clock, and the cawing of the rooks from the Cathedral tower, are like voices of their nursery time. To such as these, it has happened in their dying hours afar off, that they have imagined their chamber-floor to be strewn with the autumnal leaves fallen from the elm-trees in the Close: so have the rustling sounds and fresh scents of their earliest impressions revived when the circle of their lives was very nearly traced, and the beginning and the end were drawing close together.

Seasonable tokens are about. Red berries shine here and there in the lattices of Minor Canon Corner; Mr. and Mrs. Tope are daintily sticking sprigs of holly into the carvings and sconces of the Cathedral stalls, as if they were sticking them into the coat- button-holes of the Dean and

Chapter. Lavish profusion is in the shops: particularly in the articles of currants, raisins, spices, candied peel, and moist sugar. An unusual air of gallantry and dissipation is abroad; evinced in an immense bunch of mistletoe hanging in the greengrocer's shop doorway, and a poor little

Twelfth Cake, culminating in the figure of a Harlequin - such a very poor little Twelfth Cake, that one would rather called it a Twenty-fourth Cake or a Forty-eighth Cake - to be raffled for at the pastrycook's, terms one shilling per member. Public amusements are not wanting. The Wax-Work which made so deep an impression on the reflective mind of the Emperor of China is to be seen by particular desire during Christmas Week only, on the premises of the bankrupt livery-stable-keeper up the lane; and a new grand comic Christmas pantomime is to be produced at the Theatre: the latter heralded by the portrait of Signor Jacksonini the clown, saying 'How do you do to-morrow?' quite as large as life, and almost as miserably. In short, Cloisterham is up and doing...

V