Contents - Sean Moran

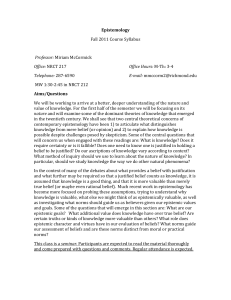

advertisement