NHS Doncaster Community Pharmacy Inhaler Check

advertisement

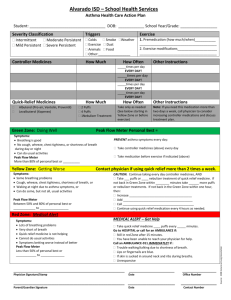

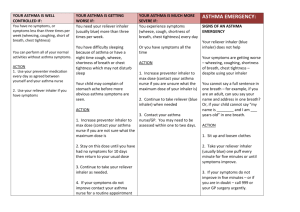

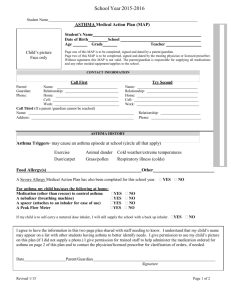

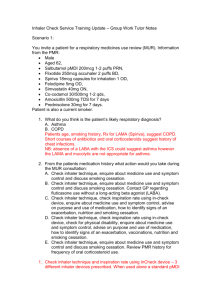

Evaluation of a Community Pharmacy Inhaler Check Service A Report for NHS Doncaster Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) May 2014 Evaluation of a Community Pharmacy Inhaler Check Service A Report for NHS Doncaster Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) May 2014 Abstract Aim and Objectives: To evaluate a Community Pharmacy Inhaler Check Service. To identify the number of patients using the service, inhaler use issues identified and interventions provided by community pharmacists, exploring patient satisfaction with the service and ideas for service development/improvement. Setting: Twenty-nine community pharmacies across Doncaster. Methods: A mixture of research methods were used for data collection: audit of 616 consultations and analysis of 577 patient satisfaction questionnaires. Audit and questionnaire results were analysed using descriptive statistics, qualitative comments using a thematic approach. Key Findings: A total of 400 patients had an initial inspiration rate (IR) out of the optimum range for their inhaler device. The majority of patients were prescribed a metered dose inhaler (MDI), 79% of these patients did not achieve the optimum IR on initial assessment. Sixty percent of patients were using one type of inhaler only, the number of different inhaler devices ranged from 13. A statistically significant relationship (p>0.001) was found between patients prescribed MDIs not achieving the optimum IR rate on initial assessment and reporting that they had not had any previous instruction. Following consultation with the pharmacist over 98% of patients achieved the optimum IR for their inhaler device. Patients expressed a high level of satisfaction with the service. Conclusion: The evaluation demonstrates the need for regular inhaler technique checks. Many patients had not achieved optimum IR for their inhaler device on initial assessment, however the community pharmacists were able to support almost all these patients to achieve the optimum IR by the end of their consultation. Community pharmacists have a key role in improving inhaler technique and inhaled medicines use, complying with recommendations made in current guidelines for asthma and COPD. The service is beneficial to patients and the wider NHS; improving inhaler use can improve condition control improving quality of life, reducing hospital admissions and even deaths, funding should continue. Acknowledgements The author of this report would like to acknowledge and thank all those who participated in and assisted with this service evaluation. Firstly I would like to thank the patients who took the time to complete feedback questionnaires during the course of the evaluation. I would especially like to thank Mark Garrison for giving up his time to help promote the service. I would like to acknowledge all the community pharmacists and their support staff who engaged with and delivered this service, and submitted data for evaluation. I would like to acknowledge the work done previously by the pilot Pharmacy Local Professional Network for NHS South Yorkshire & Bassetlaw, in particular; Matt Auckland, Nicola Gray, Richard Harris and Nick Hunter, on which this service has been based. I would like to acknowledge the contributions made by NHS Doncaster Clinical Commissioning Group in implementation and evaluation of the service, especially; Jonathan Briggs, Ian Carpenter, Martha Coulman, Dr Andrew Oakford and Emma Smith. Finally I would like to thank fellow members of Doncaster Local Pharmaceutical Committee and colleagues at H. I. Weldrick Ltd for their help and support in implementing and evaluating the service; Paul Chatterton, Michelle Foley, Richard Harris, Nick Hunter, Darren Powell, Richard Wells and especially Alison Ellis for her hours spent data inputting. This service evaluation was commissioned by NHS Doncaster Clinical Commissioning Group. Contents Page Introduction 5 Methodology and Methods 10 Results 14 Discussion 29 Conclusions 35 References 36 Appendices 38 For further information regarding this evaluation please contact: doncasterlpc@gmail.com This report was written by Claire Thomas MPharm, MSc, MRPharmS, GPhC, Doncaster LPC Member on behalf of NHS Doncaster Clinical Commissioning Group. 1. Introduction Asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) are common respiratory conditions in the United Kingdom (UK). Asthma is a multifactorial and often chronic respiratory condition that can result in episodic or persistent symptoms and in episodes of suddenly worsening wheezing (asthma attacks/exacerbations) that can prove fatal. Symptoms include; intermittent presence of wheeze, breathlessness, chest tightness and cough. Airway obstruction results from airway hyper-responsiveness and inflammation resulting in swelling of airway walls and accumulation of secretions. Triggers can include viral infections, exercise and allergens. Up to 5.4 million people in the UK are currently prescribed treatment for asthma. During 2011-12 there were more than 65,000 hospital admissions for asthma in the UK. Asthma is still killing people and the number of reported deaths in the UK is the highest in Europe.1 COPD is characterised by airflow obstruction that is not fully reversible. The obstruction does not change markedly over several months and is usually progressive. COPD is predominantly caused by smoking however occupational exposures may also contribute to the development of COPD. Exacerbations occur where there is a rapid and sustained worsening of symptoms. The airflow obstruction occurs because of a combination of airway and parenchymal damage caused by chronic inflammation that differs to that seen in asthma. COPD is estimated to affect 3 million people in the UK. It produces symptoms, disability and impaired quality of life.2 One person with COPD dies every twenty minutes in England, which is approximately 23,000 deaths a year. Death rates are almost double the average for Europe. 15% of those admitted to hospital with COPD die within 3 months and around 25% die within a year of admission.3 The mainstay of treatment for both asthma and COPD is inhaled therapy. Short-acting bronchodilators (‘reliever’ inhalers) are used when required to relieve breathlessness/wheezing. Maintenance treatment is with ‘preventer’ inhalers such as those containing corticosteroids and/or long-acting beta2 agonists (LABAs) or long-acting muscarinic agonists (LAMAs) in the case of COPD.2,4 There is a wide range of different inhaler devices on the market with different mechanisms of drug delivery in to the lungs. Examples include metered dose inhalers (MDIs) and dry powder inhalers (DPIs) e.g. TurbohalerTM and AccuhalerTM. Different devices require patients to use different inhalation techniques and inspiration rates (IR). Many patients are prescribed more than one different type of inhaler device. It is widely recognised in primary care that inhaler technique among patients is often poor.5 Whilst prescribing might be optimal, if a patient is not using their inhaler properly this can lead to poor condition control and medicines waste either lost in to the atmosphere or in to the body if the medicine is swallowed. Poor condition control can lead to more intensive management such as unnecessary hospital admissions, increased practice visits, and higher preventer inhaler doses.6 Any drug that gets into the body but not into the lungs is undesirable and can result in side effects. Beta2 agonists can cause tremor and tachycardia. Inhaled corticosteroids can cause oropharyngeal candidiasis (oral thrush) and systemic effects such as hypertension and reduced bone mineral density. Performing a check of inhaler technique and practical instruction of inhaler use by an expert should be the first line of action if a patient’s symptoms are not controlled. There is a concern that many health professionals do not know themselves how to teach inhaler technique.7 Pharmacists are all taught as part of their undergraduate course about different inhaler devices.6 Community pharmacists with their knowledge of inhaler use and frequent contact with inhaler users should be commissioned to provide services to support patients to optimise the use of their inhaled medicines. The pilot Pharmacy Local Professional Network for NHS South Yorkshire & Bassetlaw developed a respiratory support service that could be deployed within existing Medicines Use Review (MUR) or New Medicines Service (NMS) consultations. Supported by Barnsley, Bassetlaw, Doncaster, Rotherham and Sheffield Local Pharmaceutical Committees (LPCs), the project ran from September 2012 until the March 2013. Evaluation of the service concluded: most people were not in the optimum inspiration rate (IR) range for their inhaler device, however the pharmacists helped over 1,000 people achieve the range during one consultation. There was little need to contact prescribers. Most patients agreed that their knowledge and confidence had increased. By encouraging people to maintain good inhaler technique it could lead to a potential reduction in hospital admissions, GP consultations, prescribing and other NHS costs.6 There are examples of similar community pharmacy respiratory projects across the country, some of which have demonstrated reduction in prescribing costs and hospital admissions such as one in the Isle of Wight . The project, involving enhanced consultations for COPD/asthma patients, reported that reliever therapy (measured by ePACT) showed that within the first year costs of selective beta-agonists fell by 22.7% - a saving greater than seven times the initial investment by the PCT. Additionally, within 12 months, the Isle of Wight PCT was able to demonstrate that emergency admissions due to asthma had reduced by 50%, and deaths by 75%.8 NHS Yorkshire and the Humber evaluated a project where pharmacists and technicians received advanced inhaler technique training and targeted patients for respiratory MUR or NMS consultations. The pharmacists and technicians successfully retrained 97.7% of patients who had been found to be using their inhaler device incorrectly.9 In Wessex, the Inhaler Technique Improvement Project was able to show improvement in the health of people with COPD and asthma using the Asthma Control Test (ACT) and COPD assessment scores. Benefits included secondary care reduction in emergency admission, reduction in medicines waste and reduced prescribing due to improved symptom control.10 In Greater Manchester a Community Pharmacy Inhaler Technique service evaluation found that patients seen by a pharmacist showed improvements in inhaler technique, target inspiration flow rate, asthma/COPD control indicators and quality of life measures.11 Doncaster has a population of around 302,402.12 Figures from records at GP practices in Doncaster in 2010/11 show the number of patients registered with a diagnosis of COPD was 7,711 and with a diagnosis of asthma was 21,023.13. Between April 2013 and February 2014 there were 313 emergency admissions for asthma at Doncaster Royal Infirmary with inpatient costs totalling £306,127. During the same period there were 869 emergency admissions due to COPD with an inpatient cost of £1,871,651.14 Improved inhaler technique and adherence with prescribed inhaled medication may help reduce the number of emergency admissions due to COPD and asthma in Doncaster. A confidential enquiry published recently; the National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD) calls for an end to complacency around asthma care so that more is done to save lives. This enquiry from the Royal College of Physicians is the first national investigation of asthma deaths in the UK and the largest study worldwide to date.1 This enquiry found there was widespread underuse of preventer inhalers and excessive over-reliance on reliever inhalers. There was evidence of inappropriate prescribing of LABAs with 3% of patients prescribed a LABA without an inhaled corticosteroid. 10% of patients who died did so within one month of discharge from hospital following treatment for asthma; at least 21% had attended an emergency department at least once in the previous year. Nineteen percent of those who died were smokers and others were exposed to second hand smoke in the home.1 NRAD recommends; better monitoring of asthma control; where loss of control is identified, immediate action is required. All asthma patients who have been prescribed more than 12 shortacting reliever inhalers in the previous 12 months should have an urgent review of their asthma control. An assessment of inhaler technique should be routinely under taken annually and when a new device is dispensed. Non-adherence to preventer inhaled corticosteroids is associated with increased risk of poor asthma control and should be continually monitored. Where LABAs are prescribed for people with asthma they should be prescribed with an inhaled corticosteroid in a single combination inhaler device. There needs to be better education for patients to make them aware of the risks. They need to be able to recognise the warning signs of poor control and what to do during an attack.1 Current guidelines for the management of patients with COPD recommends that patients should have their ability to use an inhaler device regularly assessed by a competent healthcare professional and if necessary, should be re-taught the correct technique.2 As previous studies have shown community pharmacists have the skills and knowledge to help improve use of inhaled medication and through opportunistic targeting of patients when they present at the pharmacy they may be able to provide interventions to patients who may not routinely access services and support from their GP practices. Doncaster Local Pharmaceutical Committee (LPC) secured Winter Pressures funding from NHS Doncaster to re-commission the respiratory support service developed by the pilot Pharmacy Local Professional Network for NHS South Yorkshire & Bassetlaw in Doncaster from January to March 2014 to improve management of respiratory conditions in Doncaster. This report is an evaluation of this service. 1.1 Description of Service The service aims to improve the management of patients with respiratory conditions by trained pharmacists undertaking targeted inhaler technique training to ensure that patients use inhalers correctly. Patients aged 18 and over, including those who reside in a nursing/residential home or are housebound are eligible for the service. Pharmacies target patients who have been prescribed an inhaler and offer them a face-to-face review with the pharmacist and training in use of their inhaler, using the In-check DIALTM device. This could be part of a Medicines Use Review (MUR) or a New Medicines Service (NMS) with patients who use inhalers. The service includes a discussion about the diagnosis of respiratory disease (specifically asthma or COPD), pattern of use of different medicines (including inhaled and oral forms), and symptom control as well as assessment of inhaler technique. Pharmacies also accept referrals from other members of the health care team who consider that a patient would benefit from this service. Interventions made as part of an inhaler technique check may, but not exclusively include: advice on inhaler usage aiming to develop improved adherence, effective use of ‘preventer’ inhalers, effective use of ‘reliever’ inhalers, ensuring appropriate use of different inhaler type, identification of the need for a change of inhaler type to facilitate effective use and appropriate referral to GP or nurse prescriber when necessary. The service specification can be found in Appendix 1. 1.2 Aim: To evaluate a Community Pharmacy Inhaler Check Service in Doncaster. 1.3 Objectives: To identify whether community pharmacists can target respiratory patients to provide faceto-face consultations to assess inhaler technique and provide interventions to improve management of their condition and quality of life. Identify the number of patients using the service, the types of inhaler devices being used and technique/compliance issues being experienced by patients and the interventions being provided by community pharmacists. Explore any additional advice/patient education provided by pharmacists to improve condition management and health and well-being. Explore patient experience/satisfaction with the service. To explore feasibility of re-commissioning of the service and identify future service development/improvements. 2. Methodology and Methods Formative evaluation of the service using mixed methods was conducted to gather information regarding the structure, processes and outcomes of the service and identify any benefits.15,16 This was necessary to take account of stakeholder perspectives and evaluate how the service could be developed/improved. Quantitative methods were employed to conduct analysis of data collection records made by pharmacists during consultations and a patient satisfaction survey/questionnaire. 15,17 A questionnaire/survey method was chosen to explore patient experience rather than interviews/focus groups because it was felt more honest/open responses would be obtained using an anonymous questionnaire. There were also other disadvantages of focus groups to consider; finding a suitable/accessible venue, resources e.g. refreshments, travel for participants and the associated costs.18 A qualitative approach to explore patient experience was incorporated in to the patient questionnaire by asking patients to write additional comments. The audit and patient questionnaire methods were based on positivism and provided quantitative data for analysis. The additional comment section of the patient questionnaire provided qualitative data for analysis. 15,19 2.1. Ethical considerations This project falls within the remit of service evaluation therefore ethical committee approval was not required. 2.2 Audit A paper based data collection tool that had been designed and used in the respiratory support service developed by the pilot Pharmacy Local Professional Network for NHS South Yorkshire & Bassetlaw previously was used for data collection (appendix 1). Data was collected for consultations conducted between January and March 2014. The following operational data were recorded for each consultation in each pharmacy: Inhaler Check Service Dataset Pharmacy Code Date/Month of consultation MUR or NMS Presenting condition (asthma or COPD) Understanding of ‘control’ Any previous inhaler instruction Current oral, inhaler and other (e.g. nebulised) respiratory therapy Inhaler type/s used, with In-Check results for each inhaler type Whether target rate was achieved before leaving, for each inhaler type Frequency of preventer inhaler use Frequency of reliever inhaler use Relevant associated history (oral thrush, chest infections) Action taken (instruction only / signpost to GP or nurse / contact GP or nurse) Any other advice given Data recorded was inputted into an electronic dataset. Data collected was anonymous. 2.3 Patient Questionnaire A structured questionnaire was designed (appendix 1) including a mixture of closed questions with pre-coded response choices to enable collection of unambiguous and easy to count answers providing quantitative data for analysis. Leading questions were avoided reducing interviewer bias. A mixture of dichotomous and Likert scaled response formats were used. The Likert scale was chosen because it is easily understood and analysed.15 Information was gathered about patient sex, age, awareness of service before coming to pharmacy, ratings of understanding of condition and medicines since review, use of inhaler, explanation by the pharmacist, usefulness of advice and whether they would recommend the service to a friend. Questionnaires were given to patients in person at the end of their consultation and asked to complete it either in the pharmacy or at home. This was an opportunistic/convenience sampling method. The questionnaire explored the patients’ experience and satisfaction of using the service.15,20 2.4 Limitations The methods used may have been limited by investigator bias. The investigator was one of the community pharmacists providing the service; this may have influenced the results obtained. 2.4.1. Audit: The audit results may have been limited by information bias and poor piloting of the data collection tool.15 Due to time pressures to implement the service as soon as possible to make use of Winter Pressures funding the data collection tool was not piloted as it had been used previously. Using a paper based method of data collection resulted in some information being left blank. 2.4.2 Patient questionnaire: Questionnaire design, question wording and scale construction may have influenced the results. Patients are more likely to report being satisfied in response to a general satisfaction question using the Likert scale than they are to more open-ended, direct questions and simple ‘yes/no’ dichotomised pre-coded response choices. Codes ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’ have the potential of leading to a set response.15 Using pre-coded response choices may not have been sufficiently comprehensive therefore some respondents may have been ‘forced’ to choose inappropriate pre-coded answers. Despite these limitations the Likert scale is the most commonly used scale in health research. The results may have also been affected by recall bias and it was a disadvantage that the interviewer wasn’t present to clarify/probe and some respondents may not have understood all questions.15 Asking patients to complete the questionnaire in the pharmacy may have introduced interviewer bias and non-response bias. Patients may not have been as open and honest with their responses or may have declined to complete the questionnaire if they thought the pharmacist would see their responses. 2.5 Data Analysis The data from all pharmacies was inputted into an Excel spreadsheet. The data was then imported into IBM SPSS statistical software (version 21). This facilitated descriptive and comparative statistical exploration of the dataset, where this was possible and valid. 3. Results 3.1 Service Activity Data was provided for analysis for a total of 616 Inhaler Check Service consultations conducted between January and March 2014. Chart 1: Number of Consultations Conducted per Month (n=594) Number of consultations conducted 249 196 149 January February March There were more consultations provided in February. This could be due to the fact that pharmacist training for the service was not provided until the middle of January delaying start up of the service. Some pharmacists may have been providing the service as an adjunct to a Medicine Use Review (MUR), reaching the 400 MUR target in February or early March resulting in a drop in service provision for March. Actual activity was only 37.28% of predicted activity. The vast majority of service delivery was provided by Association of Independent Multiple Pharmacies (AIMp) and independent pharmacies. 65 pharmacies signed up to provide the service 50 pharmacies provided the service, 29 submitted data for evaluation. The number of consultations provided by these pharmacies ranged from 1-155 over the 3 month period with an average of 21 consultations per pharmacy per month. 3.1.2 MUR or NMS The majority of the consultations took place within a MUR (80.2%, n=494) 3.2 Costs Figures obtained from NHS Doncaster relating to payments made to pharmacies for providing the service between January and March 2014 totalled £5224. Average monthly spend: £1741.33 Initial set up costs/training plus service evaluation: £2337.50 Overall spend on the service: £7561.50 Estimated cost for the year if the service was to continue and activity levels are maintained: £20,896 3.3 Patient Demographics 3.3.1 Patient Age: Chart 2: Ages of Patients Assessed (=570) Percentage of Patients 28.1 24.2 20.5 13.3 7.5 2.8 3.5 18-24 25-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 Patient Age (Years) 65-74 75+ 86% of the participating patients were aged 45 or over. The mean age of the participants was 63 years, with a range from 18-98 years. 3.3.2 Patient Sex: Slightly more females (58.9%) than males (41.1%) had a consultation (n=555) Chart 3: Gender Mix in each Age Group there were more women than men in each age group with the exception of the 25-34 year olds where there were slightly more men. 3.4 Audit Results Number of Inhaler Check Service consultations audited: 616 3.4.1 Diagnosis Chart 4: Diagnosis as reported by patients (n=595) Percentage of Patients 66.4 23.4 8.6 Asthma COPD Unsure 1.7 Other e.g. bronchiectesis, infection Number of Medicines Two-thirds of patients reported asthma as their condition (66.4%, n=595), with nearly a quarter reporting COPD (23.4%). A significant minority were unsure of their diagnosis (8.6%). 3.4.2 Previous Inhaler Technique Instruction Most patients had received some previous inhaler technique instruction (68.3%, n=594) (Table 1). Patient-reported Previous Instruction Type % of consultations (n=594) Verbal instruction 39.2 Practical Instruction 29.1 No previous Instruction 31.6 Table 1 – Previous Inhaler Technique instruction reported by patients 3.4.3 Inhaler Therapy Chart 5: Type of Inhaler Used % of patients (n=616) 82.2 28.6 15.9 11.7 5.5 0.3 1.1 MDI any Turbohaler™ Accuhaler™ Easyhaler™ Clickhaler™ Twisthaler™ combination Other Inhaler The vast majority of patients were prescribed a MDI (of these, 74.8% alone, 6.8% with spacer, 0.6% with spacer and facemask). 3.4.4.Number of inhaler types used Chart 6: Number of Different Inhaler Types Used Percentage of Patients 60.6 34.4 5 1 type of inhaler 2 types of inhaler 3 types of inhaler 60.6% of patients were using one type of inhaler only (n=616). The range was from 1-3 types. Patients could have been using several different inhalers within one type, with different active ingredients (such as a salbutamol and beclometasone MDI) – but this detail was not included in the dataset. 3.4.5 Other Respiratory Therapies A small minority of patients reported having either adjunct oral respiratory therapies (9.6%) or other adjunct therapies like a nebuliser or oxygen (1.6%). Most oral therapies were not specified, but some pharmacists added notes that these were long-acting relievers or intermittent steroids. Thus inhalers were the sole respiratory therapy for most patients. 3.4.6 Patient Performance – Inspiration Rate Change Table 2 shows how many patients, regardless of diagnosis, were outside the optimum inspiration rate range at the start of the consultation for each inhaler type. It also shows how many of those people achieved the target rate by the end of the consultation. Type of Inhaler % of patients % of patients % of patients % achieving Used / Range / under target in range over target range by end of Number at first at first at first consultation MDI any 3.7 27.1 69.2 98.8 combination (30-60 l/min) (n=483) Turbohaler™ (30-90 14.7 78.2 7.1 98.7 l/min) (60-90 l/min) (n=170) Accuhaler™ 11.9 83.6 4.5 100.0 (30-90 l/min) (n=67) Clickhaler™ 0.0 100.0 0.0 100.0 (>55 l/min) (n=1) Twisthaler™ 0.0 100.0 0.0 100.0 (28-60 l/min) (n=7) Easyhaler™ (306.7 76.7 16.7 100.0 90L/min)(n=30) Table 2 – Proportion of patients (with any diagnosis) inside or outside the optimum IR range 72.9% of patients prescribed a MDI (with or without a spacer/spacer with mask) had an initial inspiration rate out of the optimal target range. 21.8% of patients prescribed a Turbohaler™ had an initial inspiration rate out of the optimal target range. 16.4% of patients prescribed a Accuhaler™ had an initial inspiration rate out of the optimal target range. A total of 400 patients had an initial inspiration rate out of the target range. Over 98% of patients achieved target range by the end of their consultation. Chart 7: MDI inspiration rate results The majority of patients using a MDI were inhaling far too fast and therefore were over the target range regardless of their diagnosis. Tables 3a and 3b (overleaf) show how many patients, with a diagnosis of asthma or COPD respectively, were outside the optimum inspiration rate range at the start of the consultation for each inhaler type. It also shows how many of those people achieved the target rate by the end of the consultation. Type of Inhaler Used / Range / Number MDI any combination (30-60 l/min) (n=318) Turbohaler™ (30-90 l/min) (60-90 l/min) (n=105) Accuhaler™ (30-90 l/min) (n=37) Clickhaler™ (>55 l/min) (n=1) Twisthaler™ (28-60 l/min) (n=4) Easyhaler™ (3090L/min)(n=22) % of patients under target at first 2.8 % of patients in range at first 23.9 % of patients over target at first 73.3 % achieving range by end of consultation 98.8 8.6 83.3 10.5 98.9 8.1 86.5 5.4 100.0 0.0 100.0 0.0 100.0 0.0 100.0 0.0 100.0 4.5 77.3 16.7 100.0 Table 3a – Proportion of patients (with asthma only, n=487) inside or outside the optimum IR range Type of Inhaler Used / Range / Number % of patients under target at first % of patients in range % of patients over target at first MDI any combination (30-60 l/min) (n=106) Turbohaler™ (60-90 l/min) (n=51) Accuhaler™ (30-90 l/min) (n=22) Clickhaler™ (>55 l/min) (n=0) Twisthaler™ (28-60 l/min) (n=3) Easyhaler™ (30-90L/min)(n=7) 3.8 31.1 65.0 % achieving range by end of consultation 98.0 27.4 70.6 2.0 97.8 22.7 77.3 0.0 100.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 100.0 0.0 100.0 14.3 71.4 14.3 100.0 Table 3b – Proportion of patients (with COPD only, n=189) inside or outside the optimum IR range The majority of patients with asthma or COPD using MDIs did not meet the target IR on their first attempt: most of them were above the optimum IR of 60 l/min. Over 20% of patients with either asthma or COPD using Turbohalers™ did not hit the range first time. Many of the Turbohaler™ patients, however, were under target. A greater number of COPD patients compared with asthma patients did not hit the optimum range first time, inhaling slower than the target rate. Patients using Clickhalers™, Twisthalers™ and Easyhalers™ (in much lower numbers) were largely successful at meeting the target IR on their first attempt. Chart 8: MDI use and previous inhaler instruction 144 patients (30.6%, n=471) prescribed a MDI reported they had not had any previous instruction. 107 (74.3%) of these patients had an initial IR out of the optimal/target range (70.1% over target). This was statistically significant (chi-square test, p>0.001). A large number of patients (161 patients/84.3%) who had previous verbal instruction had an initial IR out of range. Patients who reported having previous practical instruction performed better on initial inspiration with 74 patients (54.4%) out of range. 235 patients (49.9%) who reported having previous instruction (verbal or practical) still had an initial IR out of range. 3.4.7 Condition Control Patients with a diagnosis of asthma were asked if they knew what ‘control’ meant. Although there was a significant amount of missing data for this question (42% non response), the vast majority of patients (85.9% of the 177 asthma patients for whom data were recorded) said that they understood what it meant. Other markers of condition control were embedded within the project. Patients were asked about usage of preventer and reliever inhalers. Charts 9 and 10 show the reported frequency of preventer use and charts 11 and 12 the reported frequency of reliever use. Chart 9: Patient-reported Frequency of Inhaler Use (all patients) % of consultations (n=587) 85.3 Regularly 2.9 1.9 1.9 Sporadically When Required Not Used 8 Has never been prescribed a preventer inhaler Chart 10: Patient-reported Frequency of Preventer Inhaler Use (asthma only) % of consultations (n=385) 86.8 Regularly 3.38 2.08 1.3 Sporadically When Required Not Used There were high reports of regular preventer use from the majority of patients (84.9% of all patients and 86.7% of patients with an asthma diagnosis). Chart 11: Patient-reported Frequency of Releiver Inhaler Use (all patients) % of consultations (n=549) 31.1 27.9 20.6 13.1 7.3 At least 3 times a Once or twice a 1-3 times a week 3-6 times a week day day Hardly ever Chart 12: Patient-reported Frequency of Reliver Inhaler Use (asthma only) % of consultations (n=359) 31.8 30.6 21.7 9.7 6.1 At least 3 times a Once or twice a 1-3 times a week 3-6 times a week day day Hardly ever More than one third of patients reported using reliever inhalers at least once a day (44.2% of all patients and 41.5% of asthma patients). 3.4.8 History of other respiratory problems Nearly two-thirds (69.99%) of patients reported a past history of chest infections. There was no association between history of chest infection and knowledge of asthma control in asthma patients, nor any age-related association (chi-square test, p>0.05). A quarter (26.3%) of patients reported a past history of oral thrush. There was no association between having a history of oral thrush and whether a patient’s initial inspiration rate measured for MDI was out of the optimal target range (chi-square test, p>0.05). 3.4.9 Interventions Provided by the Pharmacist Recording of whether or not an intervention was required was poor, which may be due to limitations of the dataset.. Sixty-three percent of patients (n=388) were given at least one intervention by the pharmacist. Different Types of Interventions Delivered to Patients (n=616) % of consultations (n=616) 57.1 4.2 Inhaler Instruction 10.6 1.6 Signposting patient to Contacting the GP or GP or practice nurse practice nurse on the patient’s behalf Giving other advice Over half (57.1%) of the patients were given inhaler instruction. There were only 36 instances (5.8% of consultations) where a pharmacist signposted patients to their practice, or contacted a GP/practice nurse on the patient’s behalf. ‘Other advice’ included information about rinsing their mouth after using steroid inhalers, smoking cessation prompts, and using preventer inhalers regularly. 3.4.10 Other advice given A number of themes emerged regarding other advice given to patients by pharmacists: Difference between inhalers and when to use them Peak flow readings Correct dosage Use of spacer Timings of doses Minimising side effects e.g. rinse mouth Smoking cessation Flu and pneumonia vaccinations Allergy advice Cleaning inhaler/spacer The most frequently reported was advice about the difference between the inhalers prescribed and when to use them and how to minimise side effects. 3.5 Patient Questionnaire Results 577 questionnaires were returned for analysis. Response rate: 93.7% Questions 1and 2 provided information on patient demographics (see 3.3) Question 3: Knew the Service Existed Patients were asked whether they had known that the service existed before they used it. A small minority of patients (14.6%, n=553) had known about it beforehand. Questions 4-10: Explored patient satisfaction and thoughts regarding the service: Chart 9: Patient Evaluation of the Service Would recommend service (n=564) Advice given by pharmacist was useful (n=565) Use of inhaler has improved (n=555) More confident about their medicines (n=564) Understand more about their medicines (n=565) Explained how medicines worked (n=567) Understand more about their condition (n=567) 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% Percentage of Patients Strongly Agree Agree Uncertain Disagree Strongly Disagree 98.8% of patients agreed/strongly agreed that they understood more about their condition following their consultation. 100% of patients agreed/strongly agreed the pharmacist explained how their medicines worked. 99.1% of patients agreed/strongly agreed that they understood more about their medicines after their consultation with the pharmacist. 99.2% of patients agreed/strongly agreed that they felt more confident about their medicines. 96.8% of patients agreed/strongly agreed use of their inhaler(s) had improved following the consultation. 99.7% of patients felt the advice they were given was useful. 99.8% of patients would recommend the service to others. Free text comments from Patients Patients were encouraged to contribute their own comments about the service at the end of the patient survey. One hundred and forty-four patients chose to do so. Thematic analysis of these comments resulted in some interesting categories, as shown in Table 1.10: Theme Patient Comments “Revelation” comments “Been taking inhaler 20 years and never been offered information. shows that I have been using incorrectly. Given me very valuable new insight” “Useful as do struggle to control asthma. Previous inhaler changes have led to problems (worsened asthma / thrush and hoarseness)” “Did not realise I was not using my inhaler well until pharmacist showed me. More helpful then the hospital clinic”. “Thought I was good using inhalers but learnt a lot from the pharmacist that will help me” Pharmacists performance “No idea that using incorrectly or that compliance caused such a problem” “Very easy to understand and helped with other problems” “Pharmacist was exceptionally helpful and explained everything in detail. This made me feel more confident” “Very informative” Inhaler use “The pharmacist was very helpful and friendly” “Felt improved technique” “I will endeavour to use my inhaler correctly” “Surgery have never commented on how I used inhaler” “No one ever corrected technique before. Very useful service” “First time using inhaler” “Excellent service - would be advantageous for health professionals to revise there technique” Use of In-check device “The pharmacist agreed my technique was good” “Like breathing tube - helps understanding” “Good to be able to check way inhalers are used” “Everyone should be tested it is important” Patient education/increased knowledge “Size of mouthpiece on inhaler tester completely different to those on inhaler uses - much bigger” “Didn’t know should be using brown inhaler daily” “Too much blowing - now know I should breathe in” “Didnt realise MDI/ turbohaler should be used differently” “Very informative, learnt something new today” “Never been told to rinse mouth before” “Useful information about rinsing mouth” Quality of the service “Useful information” “Impressed with the service and will bring son in to test his technique” “Would recommend to others” “Excellent service as surgery often too busy” “Brilliant” “Very useful” “Excellent” “Big help, well worth doing” “Good confidential service” “Excellent and informative” 4. Discussion Meeting the project aim and objectives The aim of this project was to evaluate a community pharmacy inhaler check service. Although the data collection period was relatively short the use of mixed methods increased the validity of the results. The aim and objectives were met. Service Activity Actual activity was less than the predicted activity. It was difficult to accurately predict the number of patients likely to be recruited. The majority of service delivery was provided by Association of Independent Multiple Pharmacies (AIMp) and independent pharmacies. It was disappointing that service delivery from the larger Company Chemist Association (CCA) multiple pharmacies was extremely low. The short period of time the service has been running has prevented engagement with CCA senior/regional managers. Although actual service activity was lower than predicted the number of consultations provided does demonstrate that community pharmacies can provide and deliver an inhaler check service. Which is supported by findings from similar projects across England.8,9,10,11 Costs Overall spend on this service so far has been £7561.50 (including initial setup/training costs). The estimated cost for a year if service activity levels remain the same is £20,896. The average inpatient cost for one patient admitted to DRI with asthma is £978, and the average inpatient cost for one patient admitted with COPD is £2153.80. If nine COPD patients or twenty-one asthma patients improved their inhaler technique and were prevented from being admitted with an asthma attack/COPD exacerbation this would cover the cost of the service for one year. During this three month evaluation community pharmacists helped almost 400 patients who did not achieve optimal IR on initial assessment to meet the target IR for their inhaler optimising the use of their inhaled medication. Therefore the number of people who could be prevented from having an asthma attack/exacerbation could potentially be much greater than the number needed to cover the costs of the service and therefore could potentially lead to a reduction in inpatient costs, creating savings for NHS Doncaster. The short time period that this service has been running for makes it difficult to identify whether or not this service has had an impact on the number of hospital admissions for asthma and COPD. Figures provided by NHS Doncaster do show a decrease in admissions for both asthma and COPD for the period January to March 2014 compared to the same period in 2013 however it must be noted that this winter has been milder which may have contributed to a reduction in the number of people experiencing exacerbations/worsening of condition control. Service user characteristics The Service was used by a diverse group of patients, in terms of age and gender and respiratory diagnosis. The over-representation of young women reflected what is already known about pharmacy customer groups. A minority (8.6%) of users who had been prescribed inhalers were unsure about their diagnosis, and this suggests a knowledge gap that is of significant concern. Inhaler Therapy The majority of patients were using MDIs, which is in-line with current guidelines as evidence has shown that in adults a MDI with/without a spacer is as effective as any other hand held inhaler device and is cheaper.4 However it is well documented that patients find these difficult to use and have a tendency to go ‘over-target’ for IR. Seventy-three percent of patients using a MDI in this evaluation had an initial IR out of the optimal target range, with 69.2% being ‘overtarget’. The evaluation results suggest that prescribing MDIs is a false economy if inhaler technique is not checked regularly. With such a high percentage of patients using their devices incorrectly this will have a negative effect on condition control, increasing requests for ‘reliever’ inhalers and resulting in medicines waste, which may also result in side effects for the patient, as well as increasing prescribing costs. Some patients were using a number of different inhaler devices, which could be confusing. Despite the high percentage of patients out of the optimum IR range on initial assessment the community pharmacists brought over 98% of these patients into the optimum IR range for their device/s during the single consultation for the service. Further research (such as follow-up after 6 months) could explore whether the positive technique change can be sustained over time. The impact on prescribing costs could be investigated over time by analysing ePACT data. Previous Inhaler Instruction Almost a third of patients (31.6%) reported that they had not received previous instruction on how to use their device. A statistically significant relationship was found between patients prescribed MDIs not achieving the optimum IR rate on initial assessment and reporting that they had not had any previous instruction. Patients prescribed MDIs who reported having previous practical instruction performed better on initial inspiration compared to those with previous verbal instruction or no instruction. However half of those patients who reported having previous instruction (verbal or practical) still had an initial IR out of range. These results demonstrate the importance of regular practical instruction and physical checks of inhaler use to ensure patients’ inhaler use is optimised. Markers of Control The high regular preventer use reports were promising however nearly half of patients (44.2%) reported needing to use their reliever inhaler once or twice daily or more. High reliever use can be an indicator of poor condition control. Other projects have included the use of the asthma control test (ACT) and COPD assessment test (CAT) to further assess condition control, the service could be developed further to include use of such tests. Oral thrush may be caused by poor technique if steroid powder is left inside the mouth and not inhaled properly, and might thus be a marker of poor technique – the pharmacist may have an enhanced role if they had the capacity to add a spacer and facemask as needed, without the need for referral. Many of the users had a history of chest infections, which may also be a sign of poor management. Pharmacist Interventions Most people were brought into the optimal IR range by the pharmacist, therefore there was little need for contact with prescribers. The Service is self-contained, and can encourage people to concentrate on maintaining good technique. People receiving no interventions already had good technique, thus the interventions seem to have been targeted appropriately. Patient Feedback/Satisfaction Patient feedback was extremely positive. The vast majority of patients agreed that their knowledge and confidence about their medicines had increased, and that they would recommend the service to others. A number of themes emerged from analysis of additional comments which included: pharmacists performance, inhaler use, use of the In-check device, patient education/increased knowledge and quality of the service – all of which were positive. There were also a number of revelation comments such as “Been taking inhaler 20 years and never been offered information. shows that I have been using incorrectly. Given me very valuable new insight” demonstrating the perceived value of this service by patients/service users. Role for community pharmacists The evaluation results strongly support the findings of previous projects that there is a role for community pharmacists in improving inhaler use in patients with asthma and COPD. A large number of patients were helped to achieve their target IR for their inhaler device optimising the use of their medication and were provided with interventions, advice and support to maximise their medicines use, minimise side effects and improve health and wellbeing. 4.1 Limitations Time pressures to implement the service as soon as possible prevented proper piloting of the paperwork involved in delivering the service and the data collection tools. There was no time to develop promotional materials to promote the service to the public which may have impacted on the predicted numbers of patients seen. The audit enabled information to be gathered regarding the number of patients identified with suboptimal inhaler use and interventions provided to improve medicines optimisation, however this method was limited by information and investigator bias and the poor piloting and design of the data collection record sheet. There is also no information about any patients who refused to take part in the service, and thus whether there was any selection bias. Whilst every effort was made to encourage consistency of reporting among pharmacists, the paper based method of data collection did result in different ways of recording responses and there were inevitably missing data at submission. A significant amount of data cleaning was necessary before analysis. Electronic data collection would have prevented any missing data. The patient questionnaire provided an insight into patients’ views of the service and their level of satisfaction. The response rate was high minimising bias however the findings were limited by the questionnaire design and scale structure and by asking patients to complete the questionnaire in the pharmacy, patients may have been less willing to express dissatisfaction if they knew that the pharmacist would be reading their responses. This project was a retrospective analysis of previously collected data, and prospective trials would be required to confirm the results of this project. 4.2 Recommendations/Implications for practice This service should be continued. Patients were highly satisfied with the service and the advice they were given by the pharmacist. Many patients had not achieved optimum IR for their inhaler device on initial assessment, however the community pharmacists were able to support almost all these patients to achieve the optimum IR before the end of their consultation. The service is beneficial to patients and the wider NHS; improving inhaler use can improve condition control improving quality of life, reducing hospital admissions and even deaths. By continuing to fund this service NHS Doncaster would be complying with a number of the recommendations made by the Royal College of Physicians in their confidential NRAD enquiry. To develop an electronic reporting system or make use of an existing system such as PharmOutcomes to improve the completeness and consistency of the dataset. To implement a ‘fast-track’ referral system to the GP or practice nurse for patients who do not know their diagnosis, or who continue to struggle to use their inhaler despite pharmacist intervention, including a feedback loop to the pharmacist. To explore how to maximise the coverage of the Service by engaging more pharmacies in activity, so that patients consistently get recruited when they need it - whichever pharmacy they visit. The service should be promoted to raise public awareness of the service to help improve patient recruitment. Future service development: To empower the pharmacist to supply a spacer with/without mask during the consultation – without referral - where this might further improve patient MDI performance; To extend the service with one follow-up visit with the patient, in person, a month after the initial consultation, to check whether they have maintained their changes in inhaler technique and their performance for optimal IR. Patients should then be reviewed yearly. To see the patient again after any asthma attacks or exacerbations of COPD. Patients could be referred following any A&E attendances. To explore expansion of the service to include use of the Asthma Control Test (ACT) and COPD Assessment Test (CAT). To assess condition control more comprehensively. A follow-up consultation should then be conducted after 6 months to review performance with inhaler technique ad any improvement in ACT/CAT scores to measure patient outcomes. Exacerbation management for COPD patients. Pharmacists could ensure patients recognise when they need to start antibiotic treatment and ensure prompt access to antibiotics without the need to contact a GP. 5. Conclusion The evaluation demonstrates the need for regular inhaler technique checks. Many patients had not achieved optimum IR for their inhaler device on initial assessment, however the community pharmacists were able to support almost all these patients to achieve the optimum IR by the end of their consultation. Community pharmacists have a key role in improving inhaler technique and inhaled medicines use, complying with recommendations made in current guidelines for asthma and COPD. The service is beneficial to patients and the wider NHS; improving inhaler use can improve condition control improving quality of life, reducing hospital admissions and even deaths, funding should continue. References 1. Royal College of Physicians (RCP) Why asthma still kills. The National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD). Confidential Enquiry Report. RCP May 2014. 2. National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Clinical Guideline 101: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (update). NICE 2010. 3. National Health Service (NHS). The NHS Outcomes Framework 2013/14. Department of Health. 2013 4. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) and the British Thoracic Society (BTS). 101 British Guideline on the management of Asthma. A National Clinical Guideline. May 2008. Revised Jan 2012. 5. Fink JB, Rubin BK. Problems with inhaler use: a call for improved clinician and patient education. Respir Care 2005; 50: 1360-74. 6. N.J. Gray. Report of the NHS South Yorkshire and Bassetlaw Community Pharmacy Respiratory Project. Sept 2013. 7. Baverstock M, Woodhall N, Maarman V. Do healthcare professionals have sufficient knowledge of inhaler techniques in order to educate their patients effectively in their use? Thorax 2010; 65(Suppl 4): A118. 8. NICE. Isle of Wight Respiratory Inhaler Project (Shared Learning Database). Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/usingguidance/sharedlearningimplementingniceguidance/exampleso fimplementation/eximpresults.jsp?o=461 9. C. Hayward. NHS Yorkshire and Humber. Breathing in Success Project NHS Hull and NHS East Riding of Yorkshire. Oct 2013 – April 2013 10. The Cambridge Consortium. Evaluation of Inhaler Technique Improvement Programme. Cambridge Institute for Research Education and Management (CiREM). Aug 2012 11. N.J. Gray, N.C. Long, N. Mensah. Report of the Evaluation of the Greater Manchester Community Pharmacy Inhaler Technique Service. Community Pharmacy Manchester. April 2014. 12. Doncaster Together. Doncaster Data Observatory. Census 2011. Available at: http://www.doncastertogether.org.uk/Doncaster_Data_Observatory/Census_2011.asp <accessed 11/5/14> 13. NHS Commissioning Board. Outcomes benchmarking support packs: CCG Level. NHS Doncaster CCG. 2012 14. Information provided by Jonathan Briggs, Performance and Intelligence, NHS Doncaster CCG Jonathan.briggs@doncasterccg.nhs.uk 15. Bowling A. Research methods in health. Investigating health and health services. 2nd Edition. London: Open University Press; 2007. 16. Tritter J. Mixed Methods and Multidisciplinary Research. In Health Care. In: Allsop J, Saks M, editors. Researching Health qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2007. p.301-318 17. Calnan M. Quantitative Survey Methods in Health Research. Allsop J, Saks M, editors. In: Researching Health, Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods. London SAGE Publications Ltd; 2007 p.174-196 18. Green J. The Use of Focus Groups in Research into Health. Allsop J, Saks M, editors. In: Researching Health, Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods. London SAGE Publications Ltd; 2007 p.112-132 19. Davis P, Scott A. Health Research Sampling Methods. In: Allsop J, Saks M, editors. Researching Health qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2007. p.155-173 20. Alderson P. Governance and Ethics in Health Research. In: Allsop J, Saks M, editors. Researching Health qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2007. p.283-300 Appendices Appendix 1: Service Specification Service specification for delivery of inhaler technique review and training Period: 1st January 2014 to 31st March 2014 Introduction This service specification outlines the service to be provided. The specification of this service is designed to cover enhanced aspects of clinical care of the patient, all of which are beyond the scope of essential services. No part of the specification by commission, omission or implication defines or redefines essential or additional services. The pharmacy providing the service must fully comply with the The National Health Service (Pharmaceutical and Local Pharmaceutical Services) Regulations 2013 for the delivery of Essential Services and be registered with the GPhC. All staff working in the pharmacy providing the service must conform to the NHS code of practice on confidentiality. All staff working in the pharmacy providing the service must conform to the Data Protection Act. Background The aim of this specification is to enable pharmacy to play an even stronger role at the heart of more integrated out-of-hospital services for patient’s that deliver better health outcomes, more personalised care, excellent patient experience and the most efficient use of NHS resources. Service Outline This service aims to improve the management of patients with respiratory conditions by trained pharmacists undertaking targeted inhaler technique training to ensure that patients use inhalers correctly. This service should be offered to patients who meet the criteria and who are over 18 years of age. This includes patients who reside in a nursing or residential home or are housebound. This could be part of a Medicines Use Review (MUR) or a New Medicines Service (NMS) with patients who use inhalers. Pharmacies should also accept referrals from other members of the health care team who consider that a patient would benefit from this service. The inhaler technique check will be carried out face to face with the patient in the community pharmacy or in the patient’s usual place of residence. The part of the pharmacy used for the provision of the inhaler check must meet the requirements of the MUR specification for consultation areas: • • • The consultation area should be where both the patient and the pharmacist can sit down together The patient and pharmacist should be able to talk at normal speaking volumes without being overheard by any other person (including pharmacy staff) The consultation area should be clearly designated as an area for confidential consultations, distinct from the general public areas of the pharmacy. Inhaler technique checks must only be provided for patients who have been using the pharmacy for the provision of pharmaceutical services for at least the previous three months. The next regular inhaler technique can be conducted 12 months after the last one, unless in the reasonable opinion of the pharmacist the patient’s circumstances have changed sufficiently to justify one or more further consultations during this period. An inhaler technique check should not be undertaken on a patient who has, within the previous six months, received the New Medicine Service (NMS), unless in the reasonable opinion of the pharmacist, there are significant potential benefits to the patient which justify providing further training to them during this period. Interventions made as part of an inhaler technique check may, but not exclusively include: • • • • • • Advice on inhaler usage aiming to develop improved adherence Effective use of regular inhalers Effective use of ‘when required’ inhalers ensuring appropriate use of different inhaler type Identification of the need for a change of inhaler type to facilitate effective use Appropriate referral to GP or nurse prescriber The pharmacy will target patients who have been prescribed an inhaler and offer them a review and training in use of their inhaler. The pharmacy will provide and maintain all equipment and consumables necessary for the delivery of this service Accreditation The service shall be provided by a practising pharmacist, registered with the General Pharmaceutical Council of Great Britain pharmacists who has attended and completed the Inhaler technique workshops (or equivalent that have been accredited by the Local Professional Network). Payment The payment will be £10 per patient reviewed in the pharmacy. A supplementary fee of £5 per patient will be paid for home visits for patients who reside in a nursing or residential home and £10 will be paid for patients who are visited at their home address (i.e. not in a nursing or residential home). The pharmacy will be paid monthly for the number of reviews it has undertaken. Invoices should be submitted within 14 days of month end for activity undertaken in month Invoices for March 2014 should be submitted within 7 days of month end. DCCG reserve the right to withhold payment on invoices not received within these time scales. Monitoring The Pharmacy should retain a copy of Appendix A and Appendix B for their records. NHS Doncaster CCG reserves the right to review and/ or audit data in relation to payments processed for this service. Monthly monitoring should be sent to the CCG by way of an invoice detailing the following information: Number of patients reviewed The registered practice of the patient Age of patient Diagnosis Outcome; i.e. advice, treatment referred to GP, referred to another service ATT: Appendix A&B Appendix A Respiratory Medicines Use Review Service - Patient Feedback Form Thank you for having your medicines reviewed at your local pharmacy. To see if you found the review useful, we would be grateful if you could answer a few short questions. All replies are strictly confidential and it is not possible for anyone to identify you. If you have any questions about your review please talk to your pharmacist. Some Questions about you 1) I am Male/ Female (Please Circle) 2) I am………years old 3) Before your Medicines Use Review today at the pharmacy did you know that this service existed? Please rate how strongly you AGREE or DISAGREE with each of the statements below: 4) I understand more about my condition since speaking to the Pharmacist 5) The Pharmacist clearly explained how my medicines work 6) I understand more about my medicines since speaking to the Pharmacist 7) I feel more confident about my medicines since speaking to the Pharmacist 8) The way I use my inhaler has improved since speaking to the Pharmacist 9) The advice given to me by the pharmacist was useful 10) I would recommend this service to others 11) Please write any other comments you have about this service: Thank you for your help with this. Please return to the pharmacist on completion YES / NO Please rate the statements below by ticking one box for EACH statement Strongly Agree Disagree Strongly Uncertain Agree Disagree Appendix B Respiratory Service Dataset Pharmacy Code (Please tick) Date MUR/NMS* Delete as appropriate Asthma COPD Unsure Other (Please state) Diagnosis Understands 'control'? Has had previous Inhaler Instruction? Yes- Previous Verbal Instruction Yes- Previous Practice Instruction No Previous Instruction Other Respiratory treatments Tablets Type/s Used by patient Other egg. Nebuliser Initial Inspiration Rate MDI MDI+ Spacer MDI+ Spacer with facemask Accuhaler INHALER TYPE Turbohaler Clickhaler Twisthaler Easyhaler Other How often do you use your preventer Inhaler? Regularly History of Oral Thrush? Sporadically History of Chest Infections? When Required Intervention required? Not Used Inhaler Instruction only? Not Prescribed Signposted to GP/ Nurse Contacted GP/ Nurse How often do you use your reliever Inhaler? At least 3 times daily 1-2 times a day 1-3 times a week 42 Other advice given Target Rate is achieved before leaving? 3-6 times a week Hardly Ever 43