MS Word - Lake Travis ISD

advertisement

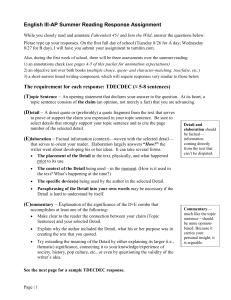

English III-AP Summer Reading Assignment While you closely read and annotate Fahrenheit 451 and Into the Wild, answer the questions on page 3. Please type up your responses. On the first full day of school, be prepared to submit your assignment to turnitin.com. The Summer Reading Assessment will consist of the following: 1) the TDECDEC summer writing assignment that is due the first full day of class 2) an objective test over both books (multiple choice, quote- and character-matching, true/false, etc.) 3) an annotations check (see pages 4-5 of this packet for annotation expectations) The requirement for each response: TDECDEC (≈ 6-9 sentences) (T)opic Sentence – An opening statement that declares your answer to the question. At its heart, a topic sentence consists of the claim (not merely a simple fact) that you are advancing about the text. And yes, use language from the question in your topic sentence answer. (D)etail –direct quotes (words, phrases, and quote fragments—not long passages or full sentences) from the text that serve to prove or support the claim you expressed in your topic sentence. Be sure to select details that strongly support your topic sentence and to cite the page number of the selected detail. *You must use at least two different details from the text for each question. (E)laboration – Factual information (context)—woven with the selected detail— that serves to orient your reader. Elaboration largely answers “How?” the writer went about developing his or her ideas. It can take several forms: The placement of the Detail (What just happened prior to its use? Beginning, middle or end of the chapter?) The context of the Detail (How is it used in the text? What’s going on in the scene or argument? Who says/asserts/does this? Why is the author/speaker/character saying or doing this? To whom is the author/character addressing?) The specific device(s) being used by the author in the selected Detail. (In a metaphor, Bradbury compares Captain Beatty to…/Krakauer’s uses imagery to describe…) Paraphrasing of the Detail into your own words may be necessary if the literal meaning of the Detail is hard to understand by itself. (C)ommentary – Commentary largely answers “Why?” and “So What?” Make clear to the reader why the details you chose connect to and support the claim in your Topic Sentence. Explain why the author included the Detail. (What is Bradbury’s or Krakauer’s purpose in creating/reporting the Detail you selected? What is the intended effect?) This is your turn to bring something to the table. Try extending the meaning of the Detail by either explaining its larger (i.e., thematic) significance, connecting it to your knowledge/experience of society, history, pop culture, etc., or even by questioning the validity of the writer’s idea. See the next page for a sample TDECDEC response. Page | 1 Detail and Elaboration should be factual information— coming directly from the text—that can’t be disputed. Commentary— should be more opinion-based because it features your personal insight and analysis; it is arguable. Or someone else may notice something different about the text. D&E is about showing a reader what the author brought to the table while Commentary is your chance to bring something to the table. Sample TDECDEC response for Into the Wild Question: How does Jim Gallien’s description of Chris McCandless in Chapter 1 reveal his conflicted view of the boy? Jim Gallien’s recollection of their car ride reveals his conflicted 1 understanding of the unforgiving Alaskan wilderness, he is impressed by Topic sentence provides a claim to defend. Notice that I’ve promised the reader I will prove TWO different ideas. the boy’s intelligence and determination. 2Gallien—recalling that 2 1 opinion of McCandless; while he seems concerned about Chris’s naïve McCandless lacked basic essentials, such as a compass, snowshoes, anti- Detail (direct quote) woven into a sentence with elaboration (paraphrased context) mosquito protection, an ax, heavy-duty boots, or a proper gun—initially finds fault with Chris, and Krakauer notes that Gallien “wondered” if Chris was “one of those crackpots from the lower forty-eight who come north to 3 Parenthetical citation with author’s last name and page number of selected detail at the end of the sentence. live out ill-considered Jack London fantasies” 3(Krakauer 4). 4Krakauer’s description of what is likely a common attitude about those of us from “the 4 Commentary that offers insight about the Detail. lower forty-eight” among experienced outdoors folk like Gallien, serves to 5 introduce an argument—that it’s easy to romanticize life in the wilderness and underestimate its dangers. 5However, 6Gallien also notes that Chris, who seemed “well educated” and who asked Gallien “thoughtful questions about the kind of small game that live in the country, the kinds of berries he could eat,” was not merely some inexperienced 7“nutcase” incapable of Transition word of contrast—signaling a shift to the second part of my thesis. 6 Start of DEC#2— Details (direct quotes) woven into a sentence with elaboration (paraphrased context) “nutcase” is such a specific word choice, so it’s quoted 7 8 9 surviving on his own (5). Despite whatever offensiveness Gallien might have felt because of Chris’s naivety, he is clearly impressed with the boy’s 8 unshakeable grit and excitement about his plan to hike into the Alaskan bush and live off the land. 10Krakauer likely chooses to begin his book with Gallien’s conflicted impression of Chris because he expects his readers to experience this same ambiguity, forcing us into a deeper examination of Chris McCandless. Page | 2 Notice, the second parenthetical citation only needs the page number 9 Commentary that connects the Detail to my Topic Sentence and then 10 attempts to explain how the Detail helps the writer achieve his larger purpose. TDECDEC Analysis Questions for Fahrenheit 451 1) What makes Montag’s experience at 11 North Elm different from the usual fire call, and as a result, how does it affect him? [Remember to make your topic sentence claim-based, not merely factual.] 2) Captain Beatty explains to Montag that over time the content of films, radio programs, magazines, and books were “…leveled down to a sort of pastepudding norm…” (51). Explain why the content of books and other media has been “leveled down” in the society of the novel. [The detail/quote from the question cannot count as one of your details.] **I recommend answering the above question only after you’ve read and annotated the entirety of the conversation between Montag and Captain Beatty (pgs. 50-59) at least twice. It’s arguably the key passage of the novel, containing a majority of Bradbury’s ideas. (From a reading comprehension perspective, it’s also one of the most difficult sections.)** 3) After reading Montag’s conversation with Faber (pgs. 76-87), answer the following question: What is a specific example of a TV show, movie, or album that you have seen or heard that, in your opinion, meets Faber’s definition of “quality.” First, using details from the text, interpret and explain Faber’s definition of “quality.” Then, include specific details (descriptions, song lyrics, etc.) from the movie, TV show, or album to support your argument that this work meets Faber’s definition of “quality.” 4) After reading (and re-reading ) Granger’s conversations with Montag (from when they meet until the novel’s end), what’s one argument about human behavior you believe Bradbury is advancing through Granger’s ideas and philosophy? TDECDEC Analysis Questions for Into the Wild 1) In Ch. 4 –What conclusions can we make about Chris’s philosophy and outlook on life based on the decisions and actions Krakauer describes? (In particular, make sure to address the flood at Lake Mead, as well as the excerpts from letters and journal entries that Krakauer includes. So, this will require a TS with two parts. Ex. Based on the decisions and actions Krakauer highlights in Ch, 4, we can conclude that McCandless values _______; additionally/however/in fact, he believes ___________. 2) In Chapter 6, Chris strongly advises Ronald Franz—especially in the letter Chris sends from Carthage, South Dakota—to change the way he is living. Summarize and explain Chris’s philosophy, which he advocates through his encouragement to Franz. As part of your commentary, describe an area of your life or behavior where you presently practice the ideas reflected in Chris’s advice and explain how your personal example reflects Chris’s philosophy. (Or...think about a specific area of your life that you feel would benefit from the philosophy Chris advises Ronald Franz to follow. Or…using examples from your life, explain why you disagree with Chris’s philosophy.) 3) Chapters 11-12 – How does Krakauer characterize Chris McCandless in these chapters? Identify and defend a specific character trait. [Quoted details should come from Ch. 11-12] 4) In Chapters 14 and 15, through the use of his own story of climbing Alaska’s Devils Thumb, what arguments about Chris McCandless is Krakauer attempting to advance and/or refute? In your analysis, make sure to address Krakauer’s thoughts on what they were both seeking, what they were both naïve about, and why. [Quoted details should come from Ch. 14-15] 5) Chapter 16-18– Although in his “Author’s Note” Krakauer suggests he desires to “leave it to the reader to form his or her own opinion of Chris McCandless,” based on these final chapters, what opinion of Chris do you believe Krakauer hopes the reader will arrive at by the end of the book? In your commentary, address whether or not Krakauer’s opinion of Chris aligns with your own and explain why or why not. [Quoted details should come from Ch. 16-18] Page | 3 What is annotating and why is it an essential skill to close reading? Annotating is a permanent record of your conversation with the text. Through marking the text and writing notes, it’s a way for you to interact with, talk back to, and join in the conversation with the author and the work he or she created. It’s important that you create an annotating system that works for you. This system might involve various symbols and highlighter colors. However, simply underlining, highlighting, or drawing symbols is not annotating; it’s the notes and comments you make in the margins that create the conversation. There is no one way to annotate a text. It can involve any of the following: defining any unfamiliar vocabulary, terms, or references to help you comprehend the text summarizing a passage or a section or a single paragraph paraphrasing difficult text into your own words—simple, easy-to-understand language recording questions that enter your mind as you read marking sentences or word choices that you feel are significant identifying important moments in the plot, such as conflict and tension figuring out the point of view of the story commenting on inferences you make about characters and how/why they change noting details about the setting, time period, culture, world of the story analyzing the author’s craft—figurative language, literary devices, description, how the text is organized, sentence structure, tone, mood, word choice, style, etc. predicting what may happen next charting your own reading comprehension—marking places that confuse you that you need to reread, further break down, or discuss marking anything the writer does—with diction, syntax, imagery, details, etc.—that intrigues, delights, disturbs, surprises, or moves you recognizing big picture thematic ideas that emerge from the text making connections between the text and your life, pop culture, society, history, etc. But doesn’t this slow the reading down? Yes, absolutely! Because annotating forces you to put on the breaks and drive slowly, you are far more likely to notice the scenery and uncover ideas that would not have surfaced otherwise. As students, many of us have mastered the art of surface (or pseudo) reading. Annotating helps thwart our scheme to merely skim and “fake read.” Other benefits of annotating: increases the likelihood that we will retain and be able to recall information from the text eliminates or greatly reduces the “I read it but I totally didn’t get it” problem makes it much easier to write about or discuss a text later on because we have notes to draw from forces us to be active and alert readers, rather than passive and disengaged readers. (This is especially important when we’re reading something we don’t like or find boring.) helps us stay awake and focused when we’re totally exhausted but need to read Page | 4 A Few Last Guidelines for Annotation Expectations: You must have a hard copy of both books, not simply an e-copy. Annotations must be done by hand—in your writing. (No, you can’t use your older brother’s book from two years ago.) For each of these books, some pages are more dense and difficult than others, so there may be some pages or passages where you make only one to a few annotations, while there will be other sections where you fill the page to the brim. Start with comprehension of the literal meaning. Before we can notice anything fancy or deep, we must make sure we understand what is happening or, especially with Into the Wild, the basic argument or claim Krakauer is making. Writing out the main idea or paraphrasing a tricky sentence into your own words is essential for basic comprehension. One technique you may find helpful is to annotate literal meaning (main idea/paraphrasing) on the left and inferences and author’s techniques on the right. *In particular, the larger red-covered copy of F451 gives you more white space, so it’s easier to annotate. When vocabulary or terms impede comprehension, you are expected to look up the word and define it (using the definition Bradbury/Krakauer uses.) *Both these books are filled with SAT vocabulary words, so it will be to your benefit to learn the words as you read. Since Into the Wild is nonfiction, in particular, you want to focus on the arguments Krakauer is advancing. Also, as you will see in the example, many of the epigraphs that appear before each chapter are connected to his overall purpose for each chapter and some are quite difficult, so don’t ignore these when annotating. Since Fahrenheit 451 is fiction, annotating for theme is essential. However, like Krakauer, Bradbury is also engaged in an act of persuasion, so pay attention to how he creates a fictional dystopian world to advance arguments about issues and behaviors in contemporary society. What Not to Do when Annotating: Don’t simply underline or highlight. You are welcome to record your own personal reactions (Ex. “How terrible!) to events in the books, but these kind of notes should not be your primary annotations. Don’t simply write “simile” or “personification” or “oxymoron.” The goal is not to simply spot and circle figurative language and devices. What’s more important is to consider why the author uses a particular device. What idea is conveyed through the metaphor? What attitude towards the subject is created with the diction? What is the purpose of this allusion? We imagine you might be feeling a little overwhelmed at this point. That’s okay. It’s normal…and good. This summer reading assignment will require some significant time and effort from you; however, we feel pretty confident in saying that the amount of time and effort you put into it will be commensurate with the amount of pleasure you derive from it. That’s true for this class as a whole. We look forward to getting to know you next school year. We’re excited that we get to begin our time together discussing these two fantastic books. While this assignment requires work and effort, our hope is that you will also enjoy this reading. Example of annotations for one page of Fahrenheit 451 and Into the Wild is on the next page Page | 5 Not every page needs to be annotated as much as these examples. The first third of books, as authors introduce us to characters and the world of a story, are especially significant. In addition, passages that confuse you—that are dense, full of difficult vocabulary, where figurative language must be decoded to unpack the author’s meaning, where you find yourself asking, “Huh?”—those are the passages that deserve the most annotation. Page | 6