![[A Trio of Seminars—Short Version: Seminar One: 15.iv.13] A Trio of](//s3.studylib.net/store/data/006878525_1-2485dab230ec7456d076fe9aa01524ed-768x994.png)

1

[A Trio of Seminars—Short Version: Seminar One: 15.iv.13]

A Trio of Seminars on Sovereignties: Seminar One*

The First Sovereignty Seminar: The Political

Peter McCormick

Political Sovereignties

Overviews

§4. Political Sovereignties: A State Sovereignty Account

4.1 A Contemporary Account

4.2 The Sovereign States System

4.3 Presuppositions and Critical Questions

Discussion Seminar One §4 and Concluding Remarks

§5. Political Sovereignties and Signs of Power

Funereal Masks and Mycenae’s “King Agamemnon”

5.1 Mycenaean Civilization

5.2 Golden Masks

5.3 After the New Archeologies

5.4 Status Burials

Discussion Seminar One §5 and Concluding Remarks

*Copyright C 2013 by Peter McCormick. All rights reserved.

Draft Only: not authorized for citation in present unrevised form.

2

§6. Burials, Institutions, and Cultural Meanings

6.1 Evolutionary Development and Decline

6.2 General Institutional Balance

6.3 Relative Cultural Pre-eminence

Discussion Seminar One §6 and Concluding Remarks

§7. Philosophical Significance: Law and Limited Political

Sovereignties

7.1 Rules, Laws, and Political Limits

7.2 The Rule of Law and the Nature of Law

7.3 Law and the Limits of Political Sovereignties

Discussion Seminar One §7 and Concluding Remarks

§8. A First Set of Interim Conclusions:

Bounded Sovereignties I

8.1 Kinds of power

8.2 Forms of political life

8.3 Results of developing dependencies

Concluding Remarks and Transition

3

In Brief

One influential account of sovereignty today1 in the history of

ideas focuses sharply on the nature of political sovereignty in

particular.

Besides providing both a series of distinctions between different

types of political sovereignties and an extensive historical

presentation of the development of political sovereignties since

the late 16th and early 17th centuries, this account highlights the

key notion of state sovereignty.

State sovereignty here is to be understood in the jurisdictional

sense according to which the bordered territories of states “are

spheres of authority exclusive to themselves.” 2

Historically, European nation states have developed a system of

state sovereignty that has several distinguishing features. This

system today has become globalized and, despite the challenges

of some alternative state systems such as those based not on

political sovereignty but on the checks and balances model, the

sovereign states model remains the major international geopolitical framework today.

Like every such overarching conceptual framework, the

globalized sovereign states system has a number of

presuppositions.

These presuppositions raise a series of critical questions. They

also suggest as well the interest of renewed historical inquiry

into the origins of European culture in the Aegean Bronze Age

1

See R. Jackson 2007.

2

Ibid., p. 149.

4

especially where much recent work has provided new

archeological, cultural, and philosophical understanding.

Inquiry into the earliest European backgrounds for an enlarged

understanding of today’s overly narrow interpretations of

sovereignty as almost exclusively political sovereignty focuses

on the idea of state sovereignty as a limited sovereignty.

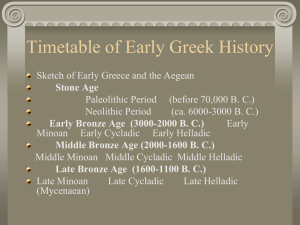

Proto-European Mycenaean culture in roughly the second half of

the Aegean Late Bronze Age (ca. 1600-1200 BCE), despite its

conquest of the Minoan culture of Crete and the destruction of

the culture of Troy in Asia Minor, arguably reached its zenith in

Mycenae itself ca. 1500 BCE.

The symbolic representations of this highpoint of Mycenaean

culture may be found especially in the golden funereal masks

entered with the bodies of the highest of Mycenae’s several

leaders in the shaft graves of Mycenae’s grave circles.

Archeological interpretations of these artifacts point to a unique

institution in Mycenae at its zenith not of a king as such but of a

king-like figure called a wanax.

Mycenae’s wanax enjoyed extraordinary political sovereignty

over his own fortified town as well as over virtually all the

Mycenaean towns of the southern Greek mainland Argolid.

Nonetheless, this political sovereignty, however extraordinary,

was clearly limited by at least two rather distant and rival

centers of political sovereignty, Pylos in Messenia and Thebes in

Boitia.3

Reflection on the character of this limited political sovereignty

indicates the importance of three of its key elements:

For putting Greek expressions into English I follow throughout the “usual messy-ish

compromise” (Osborne 2008). “The usual messy-ish compromise,” Osborne writes,

“has been made in turning Greek words into English, opting sometimes for the

traditional form, sometimes for the strict transliteration” (p. viii).

3

5

evolutionary development and decline, general institutional

balance, and relative geo-political equilibrium.

§4. Political Sovereignties: A State Sovereignty Account

In this section we take up the first of the three types of

sovereignties that these seminars will be considering in detail,

political sovereignties. We start with an influential contemporary

account from mainly a political science perspective of the meaning of

political sovereignty in its current worldwide form of the system of

state sovereignties.

4.1 A Contemporary Account

For some years now, the distinguished Canadian political

scientist and historian of ideas, Robert Jackson, has been developing a

nuanced and widely influential account of state sovereignty.4 With

others, he has underlined the fact that political sovereignty in its

modern form derives mainly from the political settlements in Europe

after the Peace of Westphalia ended the terrible catastrophes of the

Thirty Years War.

5

In this historical sense, then, political sovereignty

as we know it today is “a specifically European innovation."

6

But today

sovereignty is no longer just a European concept but now also a

globalized concept as well. “The European way of government,”

Jackson 1990, Jackson 2000, and the relevant chapters in Jackson and Sorensen

2013.

4

See for example the historical account of Philpott 2010, partially cited in the

Endnotes below, and his earlier discussions in Philpott 2001.

5

Jackson 2007, p. 144. See Jackson’s summary historical sketch of the

developments of the notion of sovereignty from the Tudor monarch Henry VIII’s 1534

Act of Supremacy to the 2005 French and Dutch rejection of the European

Constitution (pp. 2-5) which he then elaborates in three chapters, pp. 24-113.

6

6

Jackson writes, “became a global system, and the only one known to

history. The entire planet was enclosed by it.”

7

4.2 The Sovereign States System

A review of modern European history from the perspective of the

history of political ideas shows the rather constant development of

democracies from monarchies. Although there have been many

intervening stages between the early modern dominance of

monarchical forms of government to contemporary forms of

democracy,8 the number of sovereign states has continued to multiply

to our own day. This fact of increasing sovereignty has brought with it

increasing homogeneity among different populations.

Thus, “populations have been shaped into peoples, knitted

together by transportation and communications networks, political and

military mobilization, public education and the like. . . . Parliaments

have been elected by an ever widening and now universal franchise.

Aristocratic and oligarchic political factions have become political

parties.”

9

Still, however new in its continuing historical developments, the

phenomenon of state sovereignty has preserved its old foundations.

That is, the European nation states making up the European system of

state sovereignty today continue to insist on their absolute state

authority. While cooperating with the United Nations and other

international organizations, these states recognize finally no higher

governing authority than their own. In a word, there is no world

7

Ibid., p. 144.

8

Ibid., pp. 144-150.

9

Ibid., pp. 148-149.

7

government to which the sovereign authority of European nation states

is subordinated.

Although European constitutions vary widely, whether written or

unwritten and so on, nonetheless we can put this idea of the absolute

sovereign authority of those European nation states making up the

state sovereignty system in constitutional terms. Thus, European

states “continue to possess constitutional independence, which is the

liberty to enact their own laws, to organize and control their own

armed forces and police, to tax themselves, to create and manage

their own currencies to make their own domestic and foreign policies,

to conduct diplomatic relations with foreign governments, to organize

and join international organizations, and in short to govern themselves

according to their own ideas, interests, and values.”

10

It is of course true that these European sovereign states appear

to have ceded some at least some of their otherwise absolute

sovereignty to the still emerging EU. Thus, the EU’s various instances

have been authorized to sign certain agreements with non-EU states

on behalf of all the EU member states. But this authorization has not in

any way replaced the persisting sovereign powers of individual

member states to sign other agreements with non-EU states in their

own names regardless of the EU. Moreover, while certainly according

in some matters the priority of EU law over national law, EU nation

states nonetheless still reserve the priority of their own national law

over many of the most areas of state sovereignty, such as budgetary

control and defense matters.

Thus, the ongoing development of the EU as a supranational

organization does not so far entail any major cessions of state

sovereignty, as the February 2013 contentious quarrels over the next

EU five year budget demonstrated. Whether this will remain the case

over the near to mid-future seems relatively certain.

10

Ibid., p. 149.

8

The European state sovereignty system then is to be understood

today and for the indefinite future as an almost absolute form of state

sovereignty. This form can be understood relatively easily in both

jurisdictional and constitutional terms. Whether there may be good

reason for anticipating some more advanced forms of limited state

sovereignty in the European cultural values eventually to be

entrenched in a new European constitution remains unclear. For the

presuppositions of the actual European state sovereignty system

remain for the most part unaddressed in any sustained critical form.

4.3 Presuppositions and Critical Questions

What then are these presuppositions?

One effective way to identify many if not all of the

presuppositions of the actual European state sovereignty system is to

enumerate some of what most citizens in these European states

appear to assume with respect to proper government.

Thus most European citizens today live on the working

assumptions that the state in which they are citizens has clearly

defined borders. This is especially the case after the extremely

consequential following the First World War in 1922 and then those

following both the agreements among the victorious allies close to the

conclusion of the Second World War at Potsdam and the informal

adjustments following upon the reunification of Germany in 1991 and

the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1993.

After such unparalleled experiences as what some have called

“The European Civil Wars,” European state borders became sacred –

they could no longer be modified. A first presupposition of the

9

European state sovereignty system then might be called “The

Unchangeable Borders Assumption” (say, the BA assumption)

11

Most citizens also assume that there highest political

responsibilities and obligations are those deriving from their own

national governments. These governments are the highest political

authorities for the citizens of European states. Citizens’ rights and

responsibilities do not derive either from a political party, or from the

EU, or from the UN, or from any other political instance whether

European or global. We might call this second presupposition “The

Highest Political Authority Assumption” (say, the PA assumption).

Still another presupposition of the citizens of those states

forming part of the European state sovereignty system is that the laws

of their own country are those that directly apply to their activities and

that the laws of other countries have no proper bearing on those

activities. If there are EU laws, then citizens assume that only those

EU laws that are recognized by their own country’s highest legal

instances are in force. And those EU laws are in force not because of

any EU higher legal authority but only because their own particular

state has in its own right carried over these laws into their own

national sphere. Perhaps this third presupposition we might call “The

Highest Legal Authority Assumption” (say, the LA assumption).

A final presupposition for our purposes is the assumption on the

part of most citizens in their own state that, just as their own European

sovereign state is composed of citizens, so other European states are

also composed of citizens. The idea that one’s own state may also

include persons who are not citizens, or who are merely transient, or

In current international law this assumption is called, somewhat obscurely, “The

uti possidetis Principle” (“as you have, so may you hold”). This principle applies both

to a colony’s borders when it becomes a state as well as to a state’s retaining any

moveable public property “in its possession on the day hostilities ceased” ( Oxford

Dictionary of Law 2009).

11

10

who are citizens of more than one state, or who are also citizens of the

EU (as the passports of member states of the EU show on their

covers), does not ordinarily come to mind for most European citizens.

Here then is a fourth presupposition of the European sovereign state

system, one we might call “The Citizenship Assumption” (CA).

Now each of at least these four working assumptions point to

certain presuppositions of the European state sovereignty system.

Thus, this system presupposes that all actual European nation states

are territorially sovereign in the sense that their borders can no longer

be modified. Further, the system presupposes that legitimately elected

European nation state governments enjoy quasi-absolute political

sovereignty in the sense that there are no higher political authorities

to which its citizens are properly to be subjected.

Moreover, the system also presupposes similarly that a European

nation state’s legal institutions are completely sovereign in the sense

that the code of laws they administer are subject to no other code of

laws elsewhere. And finally the European system of state sovereignty

presupposes that a European nation state’s citizenship is sovereign in

that it takes absolute priority with respect to rights and

responsibilities over any other membership or citizenship in another

state or states.

But even when charitably taken together instead of interrogated

one by one, these presuppositions of the actual European state

sovereignty system raise serious issues that invite further reflection.

For as a whole these presuppositions confront reflective persons with

the basic issue of the extent of political sovereignty as such.

Can political sovereignty, under its present working

understandings in the nation state of the European state sovereignty

system, be properly understood as absolute, as quasi-absolute,or a

relative? And if relative, as arguably is the case, then to what extent

relative?

11

Concluding Remarks

Are we finally to understand at the end of these reminders from

the domains of political science and the history of ideas that political

sovereignty is in some strong sense not absolute but limited

sovereignty? Moreover, if political sovereignty is limited sovereignty,

are there good enough reasons for holding after further reflection that

political sovereignty is, necessarily, limited?

To try to get some critical distance on such issues that arise

from certain presuppositions of the European state sovereignty system

I would now like to put into discussion a historical case study. The

case in question will be one of three that I will select from the very

origins of European culture where questions of sovereignty whether

absolute or limited took a very different but nonetheless very

consequential form for our own continuing reflections today. We do

well then I believe to look for a moment at the related ideas of political

power in Mycenaean culture in the Aegean Bronze Age.

12

§5. Political Sovereignties and Signs of Power

Funereal Masks and Mycenae’s “King Agamemnon”

We begin our concerns here with enlarging current overly

political understandings of sovereignties by recalling culturally

meaningful and philosophical significant features of some of the most

important artworks from the origins of European civilization today in

the formative Aegean Bronze Age (ca. 3000 to 1200 BCE).i

We first take up several salient features only of the manifold

cultural meanings of the appearance in the middle and late second

millennium BCE of the embossed golden funerary masks of the Middle

Helladic Period Mycenaean civilization (ca. 1800-1500 BCE). The

objects come from the Argolid peninsula on mainland southern Greece

and its natural sub-regions of low mountains and valleys south of

Corinth and off the Saronic Gulf opposite the island of Aegina and

Salamis near Athens.

In order to bring out some of the philosophical significance and

not just cultural meaningfulness of these extraordinary funereal

masks, we will draw on several suggestive discussions today in both

contemporary archeological approaches to understanding the Aegean

Bronze Age and in contemporary moral and political philosophy. In the

case of archeology we will take our bearings from recent interpretive

approaches that have followed on the diversification of archeological

theorizing at the outset of the new millennium.

And in the case of moral and political philosophy, which we have

not yet written up here for these preliminary seminars, we will take our

bearings from debates about the nature of those ethical and political

values at issue in the quite important ongoing discussions between

two internationally distinguished philosophers of law, Ronald Dworkin

and Scott Shapiro, about, in particular, political sovereignties.

13

We will come to find that an historically representative preamble

to any eventual EU constitution would do well to make room for

incorporating at least some of the ethical and political values of norms

and lawfulness that may emerge from fresh interpretative reflection on

several of the deeply suggestive Mycenaean origins of Europe today.

5.1 Mycenaean Civilization

We may begin by stepping back from the well-known

catastrophes of the Persian Invasions of mainland Greece of 490-480

BCE to an earlier and less well-known set of catastrophes in roughly

the mid-1500s BCE. These events took place quite close to the very

cultural beginnings of Europe that began to terminate the most

successful period of Mycenaean Civilization at the end of the Early

Palatial Period.ii And it is just here that we come upon some of the

most extraordinary artworks of that civilization.

Archeologists have uncovered these buried artworks and those

like them within fortified citadels and various kinds of graves in the

Argolid at Mycenae, Epidaurus, Argos, Tiryns, Nauplion, Asiné, and

Midea and at Lerna on the Argolic Gulf across from Nauplion. They are

dated to roughly the late sixteenth century BCE.

What archeologists today call “Mycenaean Civilization”

12

encompasses a variety of quite different sites and finds first centered

mainly in the hilly Argolid region on the north-east corner of the

Peloponnese. Later in their history, the mainland Mycenaeans invaded

many of the Aegean Islands as well as Crete (from about 1450 BCE).13

In general, for Mycenaean civilization see Bintliff 2012, pp. 181-205, with

bibliographies, Chadwick 1976, Shelton 2010, pp. 139-148, Wright 2008, and Crowley

2008. For the Greek texts see especially Duhoux and A. Morpurgo Davis 2008-2011.

12

14

Some hold that, in alliances with other cities of Achaia and the

Peloponnese, they also besieged Troy,14 the Ilios of Homer15 (who

refers to “Asiné” but once), on the Anatolian or Ionian coast.iii In

central and eastern Crete they established a thriving province of its

own centered on the much older conquered palace city of Knossos.

Mycenaean culture reflected closely the contemporaneous

somewhat severe high palace cultures on the Greek mainland. But the

more developed Cretan palace cultures continually enriched the later

Mycenaean culture that conquered them. For multiple reasons,

however, and very much like other cultures in the very late Aegean

Bronze Age, Mycenaean civilization itself collapsed roughly in the

period from 1200-1150 BCE.16

Each of these archeological sites on Greece’s southern mainland

of course has its own history, and several have their own archeological

museums.iv But the major part of the most important artifacts

discovered in the later Argolid Mycenaean cities such as in Mycenae

itself as well as in Epidaurus,17 Argos,18 Tiryns,19 and others, are still to

be found in the extraordinary collections of the National Archeological

Museum in Athens.20

13

Morkot 1996, pp. 26-27.

14

Jablonka 2010.

15

See Morris and Powell 1997.

See the nuanced discussion in Bintliff 2012, pp. 184-185. For the collapse of the

Aegean Bronze Age generally see Deger-Jalkotzy 2008.

16

17

See Finley 1977, pp. 160-161.

18

See Finley 1977, pp. 158-159.

19

Maran 2010.

15

Here, we may consider briefly the Mycenaean masks and crowns

found in the so-called “Treasury of Atreus”

v

at Mycenae,21 the place

that Homer, in one of his many memorable epithets, called “rich in

gold.”

5.2 Golden Masks

Perhaps the most important of the several embossed golden

masks from Mycenae and from other related sites in late Helladic

Period Greece is the so-called “Mask of Agamemnon,” now on view in

the outstanding Mycenaean Collection of the National Archeological

Museum of Athens.22

In the 1870s, when Heinrich Schliemann discovered this quite

beautiful artifact used to cover the face of an immensely wealthy royal

personage, he believed that the mask was the death mask of

Mycenae’s historical but also much fabled King Agamemnon.23

Accordingly, Schliemann thought that the mask was to be dated from

sometime in the thirteenth century BCE. Later examination, however,

demonstrated that the mask was to be dated more accurately from the

mid-sixteenth century and hence could not be Agamemnon’s. But the

name Schliemann gave the mask remains to this day.

Schliemann uncovered the “Mask of Agamemnon” in Grave V of

20

Zafiropoulou 2009.

21

See French 2002, and French and Iakovidis 2003.

Demakopoulou 2009. Colour photographs of selected Mycenaean materials can be

seen in Iakovidis 1979, pp. 54-65, and in Demakopoulou 2009, pp. 17-23.

22

23

For the history of archeology see Trigger 1995.

16

Grave Circle A of the royal shaft graves24 of the Mycenaean royal

leaders or “kings” in the fortified acropolis of Mycenae in the Argolid

dominating the Argos plain to the south-east. The golden mask was but

part of the many luxurious funerary objects25 which Schliemann

discovered in 1877 in the six tombs of Grave Circle A dating from ca.

the 1500s. Very much later, in 1951, archeologists discovered many

other richly fabricated grave goods in the still earlier tombs of Grave

Circle B.26

Besides the so-called Mask of Agamemnon in Grave V of Grave

Circle A, Schliemann also discovered two other gold embossed

funereal masks in Grave IV of Grave Circle A. Accompanying the two

masks from Grave IV were a golden drinking vessel, called a rhyton,27

in the form of an lion’s head and a silver rhyton in the shape of a bull’s

head. Also found in Grave IV and in Grave V accompanying the Mask of

Agamemnon were bronze dagger blades elaborately but rather severely

inlaid with gold, amber, and a black precious filling called niello.28

These items were deposited with the bodies in the royal tombs as

part of elaborate funeral services whose details have only very

gradually come to light.29

A recent and brief overview of the peculiar nature of these shaft graves and the

two shaft grave circles (Shaft Grave Circles A and B) is in Bintliff 2012, pp. 171-172.

24

Photographs are in Higgins 1997, p. 153 and pp. 138-139; Preziosi and Hitchcock

1999, p. 151; and in Iacovidis 1979, pp. 60-65.

25

This tomb circle is called “Grave Circle B” instead of “Grave Circle A” because of

its discovery only after the discovery of the chronologically later Grave Circle A.

26

A rhyton is “a type of drinking vessel, often in the form of an animal’s head, with

one or more holes at the bottom through which the liquid can flow” (ODE).

27

Niello is “a black composition of sulphur with silver, lead, or copper, for filling

engraved designs on silver or other metals” (ODE).

28

17

While keeping in mind the artifacts that daggers accompanied in

these royal graves, comparing and contrasting briefly the three golden

funerary masks with each other is instructive. Since archeologists

consider the Mask of Agamemnon from Grave V to be perhaps the most

expressive of these objects, we may best begin with the two other,

reputedly less expressive masks from Grave IV. But first we need to

recall the situation of Aegean Bronze Age archeology today.

5.3 After “The New Archeology”

How are we to understand these extraordinary artifacts in

general and in particular the golden funerary masks and warrior arms?

Methodological approaches in archeology have developed very

greatly since the 1960s when traditional methods dating from the late

nineteenth century continued largely unchanged after the First World

War.30 Some of these newly developed approaches became so

important as largely to merit the name, “The New Archeology.”

Most archeologists began to use this expression to denote mainly

the characteristic and persistent application of recent scientific

developments and instrumentation, including information technology,

not just to the description but also to the explanation and

understanding of archeological artifacts.

The New Archeology, however, quickly inspired a reaction among

some more strictly historically oriented archeologists. Many of them

argued that, however helpful and often even necessary new scientific

methods and technologies might be, such approaches were not

29

See Cavanaugh 2008, pp. 337-339, and Bintliff 2012, pp. 192-194.

30

Cf. Johnson 2010 and Hodder 2012.

18

sufficient in themselves to elucidate adequately many archeological

items. On their view, exclusively scientific approaches could not deal

fully satisfactorily with many of the cultural and symbolic aspects of

the artifacts, assemblages, features, and sites that archeology studies.

The result was the emergence recently of more nuanced

approaches, at least to the interpretation of many artifacts if not to

their scientific descriptions and functional explanations. Studies

especially of the symbolic aspects of artifacts have led to still further

development of such rather traditional subsections of archeology itself

as social archeology31 and archeology and anthropology.32 Moreover,

these studies have led even to the relatively new subdivisions of

cognitive and even neuro-scientific archeology.33

When we return then to trying better to understand the artifacts

at issue here, the golden funerary masks and military arms of the

heyday of mainland Mycenaean civilization in the Argolid as well as

other artifacts we will be considering below, I think we do well to

consider briefly their cultural meaningfulness under the various

headings of the newer, more interpretive, or so-called “postprocessual”

vi

kinds of contemporary archeology.34

We may then leave for the professionals some of the importance

and interest of the many controversial chronological issues,

geomorphological, chemical, and paleo-botanical problems, and here

the metallurgical details as well. And perhaps we may focus more

broadly on the general elucidation of the architectural contexts and

cultural indices surrounding the find sites of these artifacts.

31

Cf. Renfrew and Bahn 2012, pp. 169-222; cf. Insoll 2011.

32

See for example Flannery and Marcus 2011 and the review by Turchin 2013.

33

Renfrew and Bahn 2012, pp. 381-420; cf. Renfrew and Zubrow 1994.

34

Renfrew and Bahn 2012, pp. 43-45.

19

5.4 Status Burials

As we have noted already, these artifacts are found in several

Mycenaean tombs dating from roughly the middle of the sixteenth

century BCE. The tombs are of a special sort. They are found inside a

special construction. That construction is situated at a special place.

And the site itself is to be found in an unusual locale. We may take

these briefly in reverse order.

Archeologists unearthed these particular funerary artifacts at

Mycenae at the northern edge of the Plain of Argos in the Argolid

Peninsula. Mycenae was but one of four Mycenaean settlements there,

each situated at one of the respective cardinal points of the Plain of

Argos, which also included the settlements of Argos itself as well of

Tiryns and Midea.35

For some time, however, until it came to surpass Argos itself as

the most important settlement bordering the Plain of Argos, Mycenae’s

relative status among the other Plain of Argos settlements remained

unclear. Moreover, when Mycenae finally did achieve political

preeminence over Argos, whether Mycenae became then merely a first

among equals or the clear leader in “a four-tier settlement hierarchy”

36

remains unclear even today.

But what does seem rather evident is that Mycenae achieved a

leadership position as a state-run palatial redistributive economy amid

the Argolid Mycenaean settlements. And this was the case even if the

very important Mycenaean settlements at Pylos in Messenia and

Thebes37 in Boeotia38 continued to be its rival.39

35

Marzolf 2004.

36

Bintliff 2012, p. 186.

37

For Thebes see Dakouri-Hild 2010b, esp. pp. 694-696.

20

The major index that shows the political pre-eminence of

Mycenae at this period is the rather sudden appearance of the

prestigious, very high status type of tomb called the tholos tomb. The

tholos tomb occurs first in Pylos in Messenia. But the buried objects

from Mycenae are not just in tholos-type tombs but in the still more

distinctive shaft-grave sub-type of tholos tomb.

The shaft-grave sub-type of tholos tomb has the highest status

level of all the Mycenaean tombs of this period, from the archaic pit

and cist graves, to the most common chamber tombs, to the tholos

tombs themselves. 40 The archeological record shows that at one point

elites in Mycenaean Pylos41 in Messenia in the southwest of the

Peloponnese ceased to build such tombs. But subsequently the

building of such tombs first became the prerogative of the wealthy and

powerful Mycenae elite and finally the privilege of “the uppermost

princely dynasties” in Mycenae alone.42

Later, the wealthy and powerful in Tiryns, Lerna,43 and Asiné

seem to have imitated these tombs.44 But, to date, the nine tholos shaft

tombs found at Mycenae are the highpoint of Mycenaean status burial

sites. This evidence of high status burial sites becomes one of the

bases for the archeological view that sees Mycenae reaching the peak

38

For Boeotia see Dakouri-Hild 2010b, esp. pp. 617-619.

39

Bintliff 2012, pp. 185-186, and 193.

40

Cananagh and Mee 1998, and Mee and Cavanagh 1990.

41

Davis 2010, esp. pp. 683 and 697.

42

Bintliff 2012, p. 193.

43

Wienke 2010, esp. pp. 664 and 667.

44

Ibid. See also Voutsaki 2010, pp. 603-604.

21

of its power with the construction of the shaft grave burials with their

extraordinary golden artifacts.

A further point in favor of this hypothesis is that the particular

shaft graves in which these objects are found at Mycenae, Shaft

Graves IV and V, are among those to be found inside and not outside

the so-called “Grave Circle A” that Schliemann first uncovered on the

west side of the Mycenae acropolis. The Mycenaean elites constructed

Grave Circle A and the somewhat earlier circle45 Grave Circle B that

encloses these shaft graves at the summit of the acropolis as

presumably a place of quite special dignity reserved for their very

highest leaders.46

These leaders must have been particularly resourceful. For “the

extension of the citadel to the west to enclose the Grave Circle and

the Cult Center,” as one specialist has written recently, “was a very

considerable enterprise and must have commanded the city’s full

resources. The plan included changing the approach, constructing a

monumental gate (the Lion Gate . . .) and completely altering and

refurbishing the Grave Circle . . . at a higher level to make a singularly

impressive sight to one entering the walled acropolis.”

47

The person

who issued such commands must have been the leader himself of a

settlement, the settlement having now become perhaps the leading

city of the Mycenaean culture itself.

This person or his immediate predecessors or followers were

those who were buried in Shaft Graves IV and V with the golden

As already noted, these tombs were discovered later and hence called according,

to the order of discovery and not to the chronological order, “Grave Circle B.”

45

Cf. French 2010, p. 673. French reproduces annotated maps of both Greater

Mycenae and Mycenae from the Mycenae Archive resources available to scholars.

46

47

Ibid., p. 675.

22

funereal masks and the warrior arms. Such a person was the leader of

Mycenae. He was no longer merely a chieftain, or a so-called “Big

Man,” the leaders of earlier much less developed settlements.

Who was this person? He was perhaps a king-like figure. Most

probably this person was what the Mycenians themselves called not a

“lawagetas” or “leader of the people,” but a “wanax” or “supreme

leader.” This is what Homer had in mind when he called Agamemnon

the “wanax” or “lord of men.”

48

What we need to note in particular, however, is that the sixteenth

century Mycenaean king-like figure, or wanax, could not have at that

time exercised absolute political sovereignty over the Mycenaen

civilization. For there were members of his own presumably dynastic

family to consider. There were also the leaders of the rival cities of the

Plain of Argos, especially of the Argos elites who wanted to reassert

their earlier dominance.

Farther away to the southwest were the elites of Homer’s “sandy

Pylos” who were still developing their own power, perhaps more

intermittently than those of Mycenae but nonetheless rather steadily.

And there were above all the elites of Mycenaean Thebes not so far

away to the northeast whose appetites for eventual absolute

sovereignty49 were still tempered by their rivals in Orchomenos.50 That

is to say, the political sovereignty of the Mycenaean lord or wanax was

not an absolute but a truly limited political sovereignty.

48

Shelmerdine and Bennett 2008, pp. 290, 29O, and 292 respectively.

Partially evident perhaps in their construction of the island fortress, Gla, at the

northeast of Lake Copias in central Greece. See Bintliff 2012, pp. 190-191 and the

aerial photograph reproduced from Schoder 1974.

49

Cf Bintliff 2012, pp. 192-199. Note that Mycenaean Linear B tablets do not include

any political and diplomatic archives. See Palaima 2010, esp, pp. 358-359.

50

23

We need then to investigate first just what such a limited political

sovereignty might mean in itself, and then second to specify if we can

the philosophical significance of such a limited political sovereignty in

the contexts of an eventual prelude to an EU constitution.

24

§6. Burials, Institutions, and Cultural Meanings

6.1 Evolutionary Development and Decline

When from the perspective of our concerns with enlarging today’s

rather constricted understandings of sovereignty as almost exclusively

political or state sovereignty, we look back over these brief reminders

about Mycenaean culture at the origins of European civilization,

several considerations are salient. Perhaps foremost is the idea of a

culture’s rise and fall.

Mycenaean culture, like the several major Aegean Bronze Age

cultures that preceded it, namely the Minoan culture and the still

earlier Cycladic culture, developed in what might be called, rather

roughly,51 an evolutionary fashion.

52

The importance of this general point is that any attempt to

interpret not unsatisfactorily such material remains of this culture as

the golden artifacts of the high status burials in Mycenae must always

struggle with difficult matters of dating and chronology. For the

cultural meanings53 of such artifacts are necessarily rooted in a

particular moment of that culture’s development. Thus, the dating of

the burial of the so-called golden mask of Agamemnon matters much.

This is very important qualification given the notable failings of “cultural

evolutionism” dating from E. B. Tayor’s nineteenth-century work on the so-called

“cultural evolution” of religious beliefs. Some of these failings appear to be still

prevalent in several otherwise distinguished anthropological works today. See for

example the critical comments of Bashkow 2013 in his review of Diamond 2013.

51

“The idea of evolution has been of central significance in the development of

archeological thinking” (Renfrew and Bahn 2012, p. 27.). See for example White 1959.

52

53

On cultural meanings and archeology see Renfrew and Bahn 2012, pp. 381-420.

25

For if such an elite burial dates from a period in the particular

history of the settlement at Mycenae that is contemporaneous with the

elite burial practices of the Mycenaean settlement at Pylos, then one

might reasonably find in it much less cultural meaning than if it dates

from a later period when the elite burial practices at Pylos had already

ceased. In the first case, the golden artifacts found in the Mycenaean

elite burial sites would have to be compared with other fine artifacts

found in the Pylos sites. In the latter case, however, the Mycenaean

golden artifacts, with all their implications of not just high but perhaps

even of royal status, would have rather different cultural meanings.

Archeologists today are reasonably sure that the dating of the

Mycenaean artifacts are subsequent to the dating of the Pylos

artifacts. Accordingly, there are reasonable grounds for thinking that

the Mycenaean artifacts had a particularly strong cultural meaning in

terms of political leadership. Indeed, some would argue, as we have

noted, that Mycenae at this period was not just first among equals

amidst the three other major Mycenaean Argolid settlements; it was

pre-eminent. That is, Mycenae at this period exercised pre-eminent

political sovereignty over the Argolid.

6.2 General Institutional Balances

Looking back through the reminders we have assembled above

about Mycenaean culture, however, we come quickly upon another

salient point. This point is a linguistic one.

We recall the hesitations some archeologists still entertain about

the difficult issue of how exactly to characterize the pre-eminent

leader or leaders of Mycenae. Where Homer appears to have had no

doubts about the status of Agamemnon as King of Mycenae, today’s

archeologists hesitate to speak of Mycenae’s rulers as kings and

26

royalty.

Perhaps these hesitations are not fully grounded. Nonetheless,

even so astute an archeologist as Schliemann himself jumped all too

quickly to the rash conclusion that the golden mask he had uncovered

was the mask of King Agamemnon. Yet when the specialists had

finished their scientific investigations it turned out that the mask in

question was much older than any mask of the historical King

Agamemnon could have been. So the question arose as to whether at

that particular period in the development of Mycenaean culture the

indisputable elite burials were the burials of kings and royalty properly

speaking, or rather of pre-eminent leaders to be identified in other,

perhaps related but still quite different terms.

In these contexts the proposal arose that the elite burials in the

Mycenaean Shaft Graves of this period contained the remains of at

least several individuals who during their lives were not known

precisely as “kings” but as wanax. And once again, just as in the case

of the contemporaneity or not of the elite burials at Mycenae and

Pylos, the question arose as to whether, unlike a city-state’s king, a

Mycenaean settlement could have at one time more than one wanax.

Of course we cannot predict the future results of further

investigations of the Mycenaean settlements in the Argolid, in

Messenia, or in Boiotia. Perhaps further discoveries will resolve this

question definitively one way or another.

But right now we can already see that if the political structure of

Mycenae allowed of more than one wanax at the same time, then

however extensive the political sovereignty of a wanax was, it was

certainly not unlimited. That is, Mycenaean political sovereignty in the

period under discussion was perhaps limited not just regionally, as the

still controversial relative datings of the Pylos elite burials might

suggest. Perhaps Mycenaean political sovereignty was also limited –

27

and this is the second point -- with respect to any claim to individual

uniqueness.

6.3 Relative Cultural Pre-eminence

Reviewing still further the brief reminders of several of the most

remarkable features of Mycenaean culture when Mycenae itself was

arguably at the apogee of its cultural development brings into view a

third and for now final point. For whatever the indisputable military

powers of Mycenaean culture that enabled this mainland settlement to

project its interests to Crete and even to install that power at some of

the very culminating sites of Minoan culture such as Knossos,

Mycenae seems to have enjoyed even at its greatest extent less than

any properly speaking absolute political sovereignty.

Recall that Mycenae certainly gradually developed its own

cultural identity in the Argolid in conjunction with the other key

Mycenaean settlements there. Perhaps Mycenae was also able to rise

to a position of at least first among equals if not pre-eminence before

the consolidation of its commanding positions in Crete.

Still, archeologists have not had great difficulty in demonstrating

that much of Mycenaean culture generally in this period betrays the

almost overwhelming influence of Minoan culture on the Mycenaeans.

Although the historical situation of the Mycenaean occupation of

Knoss, for example, must certainly have evolved over time,

nonetheless the general cultural relationships between Mycenae and

Knossos seem to have been rather stable. What were those

relationships?

The Mycenaeans who establish themselves by conquest at

Knossos were certainly not to be understood as military barbarians

without any culture of their own. We have already seen just how varied

28

and extensive Mycenaean culture was before the spreading to Crete.

That culture we know was far more extensive than simply the

construction of elite tombs. The architecture, the social organisations,

the complex diplomatic relations among the different Argolid

settlements, and so on – all testify to an extensive indigenous culture.

Still, many archeologists have come to believe that, however

extensive their own culture was and however dominant their own

position as conquerors was in Crete, the Mycenaeans who came to

Crete fell quickly under the cultural influence (some would say

dominance) of the Minoans. For the Minoans represented not only an

older culture than the Mycenaean; the Minoans had developed that

culture to a greater degree than the Mycenaeans had developed their

own.

The evidence stood before the eyes of the Mycenaeans when

they occupied the palace at Knossos with its truly extraordinary

architecture, spaces, frescoes, and so on. Moreover, even more

impressive to the Mycenaeans was the testimony to a higher cultural

achievement of the conquered Minoans furnished by their now written

languages. For, in settling themselves comfortably at Knossos and

perhaps also at Phaistos, the Mycenaeans came upon not only Linear A

and Linear B scripts; they also came upon the so-called pre-palatial

Archanes script.

54

What very much seems to be the case, then, is that Mycenaean

political sovereignty was not only limited individually and regiona lly

but even more so in terms of the larger world. No Mycenaean leading

political figure visiting the conquered territories of Crete could neglect

the evidence of his eyes. However powerful his armed forces, that

leader’s cultural pre-eminence could no longer be simply assumed. For

the extraordinary extensiveness of Minoan cultural developments

54

See Tomas 2012 in Cline 2012, pp. 342-343.

29

clearly demonstrated that the political sovereignty was now limited in

at least a third and truly significant way. Mycenaean political

sovereignty seems to have also been limited culturally.

30

§7. Philosophical Significance: Law and Limited Political

Sovereignties

When we look back through the analyses of sovereignty in the

almost exclusive terms of political state sovereignty, and then the

descriptions and apparent cultural meanings of the signs of Mycenaean

political powers, we come upon the realities of definite limits. In this

final section of Seminar One we now need to reflect on the nature of

these limits on both the historical realities of Mycenaean power

politics and their philosophical suggestiveness with respect to the

nature of limited political sovereignties.

7.1 Rules, Laws, and Political Limits

Both the history of the European early modern period at the time

of the Peace of Westphalia after the Thirty Years War of 1618 to 1648

and the history so much earlier towards the end of the European

Aegean Bronze Age of the Mycenaean ascendancy from roughly 1500

to 1200 BCE, show the omnipresence of regulations and rules. For each

widely separate period in European history in however different ways

shows many of the hallmarks of the political state. Above all, there is

the centralization of economic, social, and individual power based

upon a relative monopoly of military dominance.

Contemporary political science and social theory, however, have

taught us rightly that such degrees of centralization are impossible

without the imposition of strict behavioral guidelines, regulations, and

rules for governing groups of people with individual needs, interests.

Moreover, whatever the differences in both the Westphalian and the

Mycenaean cases, the imposition of such different kinds of effective

governance rules is physically enforced. And in both cases the

31

instruments of physical enforcement are various forms of military

force.

The evidence of such enforced regulation is of course quite

different in each case. For the order that the European state leaders

imposed on their peoples at the end of the Thirty Years War we have,

most notably, fully preserved written evidence in the form of the Treaty

of Westphalia. For the order, however, that the Mycenaean leaders

imposed on their peoples at the zenith of their hegemony over the rival

towns of the Argolid we have but partially preserved monumental

evidence in the form of extraordinarily made ashlar fortifications and

golden funerary artifacts. But, however different the character of this

evidence, in each case such evidence could not exist without the

conditions of rule-governed political, social, and individual behaviors

having been fully met.

The central point here then becomes apparent. For groups of

people to succeed in organizing their lives with sufficient security and

well-being, rules of some sort and their physical enforcement are

necessary. What forms these rules and their enforcements take,

however, are contingent on various factors such as climate,

geography, demography, and so on. But among the most important

factors shaping these contingent forms of regulation and enforcement

is the relative social development of the groups in question. And to

some important degree this social development can be measured.55

In some but not all cases of socially developed societies the

necessary rules for the governance of complex groups assume the

form of laws. In the history of European civilization, rather

compendious lists of inscribed laws appear quite early, for example in

the law codes56 of Hammurabi in Babylon or in the early Israelite law

55

Morris 2010, pp. 623-645, and Morris 2013, pp. 1-52.

56

In general see Grandpierre 2010, pp. 275-285 and in particular Roth 1997.

32

codes in the Hebrew Bible’s books of Leviticus and Numbers.57 But

before such inscriptions of law codes, oral rules surely most have been

prominent. And, as the Israelite sources show, some of these oral

prescriptions were surely law-like.

Thus, effective social groupings, the archeological and historical

records show, required kinds of organized rules and regulations, that

properly enforced, sometimes assumed the form of inscribed or written

laws that governed and thereby limited both individual and social

behaviors.

If we now narrow our concerns to the nature of the law itself, we

may come to understand somewhat better just how not just rules and

regulations but also and pre-eminently laws themselves necessarily

limit sovereignties.

7.2 The Rule of Law and the Nature of Law

The major principle of social organization in both the Aegean

Bronze Age Mycenaean societies and in the Early Modern European

societies, one might be tempted to say, was one that both held in

common, although in different forms. This major principle was finally

“the rule of law.” In the case of Mycenae, the rule of law was

effectively what the ultimate leader, the wanax, wanted; in the case of

the Westphalian polities, the rule of law was effectively what the

treaty codifed.

This view however would be mistaken. For although so-called rule

of law in so far as it specifies rules and regulations, penalties and

punishments that allow for the effective governance of social groups

whether in the Bronze Age or in Early Modern Europe, might appear to

57

In general see Knight 2011 and in particular Coogan 2010; pp. 141-245.

33

be a common European cultural inheritance, in fact the rule of law is

an expression that is rife with ambiguities.58 Moreover, the rule of law

is opposed to the rule of despots which could arguably have been the

case in either Mycenae or in one of the Westphalian states.

The discussion today of just what constitutes the rule of law goes

back mainly to the important work of the late nineteenth century,

Oxford Professor of Law, A. V. Dicey.59 And commentators today

continue to interpret both the matter itself as well as Dicey’s own

views in remarkably different ways.60 One of the most authoritative and

recent works on the concept of the rule of law summarizes the core of

this notion as currently understood: “all persons and authorities within

the state, whether public or private, should be bound by and entitled to

the benefit of laws publicly made, taking effect (generally) in the future

and publicly administered in the courts.”

61

Now such an understanding will not fit either the Westphalian or

the Mycenaean cases, for neither could satisfy at once all the

conditions here, however few. The rule of law on current understanding

then is “not comprehensive and not universally applicable.”

62

Nevertheless, once the expression is examined carefully, one comes

upon a more elaborate representation of the rule of law that can help

us see the differences between the ancient and the modern

Cf. a standard definition of “the rule of law” as “A system of governmental behavior

and authority that is constrained by law and the respect for law in contrast to

despotic rule” (Bedau 2005).

58

59

Dicey 1945.

60

See Bingham 2010, pp. 3-5.

61

Ibid., p. 37.

62

Loc. cit.

34

understandings of the regulatory nature of the effective governance of

human societies.

On the same distinguished reading this elaboration of the rule of

law involves at least eight major claims that we may cite as follows.63

“The Accessibility of the Law (1) The law must be accessible and

so far as possible intelligible, clear and predictable” (p. 37).

Here, if intelligibility and clarity are reasonably to be found in both of

our test cases, predictability is problematic in the ancient one.

“Law not Discretion (2) Questions of legal right and liability

should ordinarily be resolved by application of the law and

not the exercise of discretion” (p. 48).

Here, both the early modern and the ancient cases would seem to

award a strong place to discretion.

“Equality Before the Law (3) The laws of the land should

apply equally to all, save to the extent that objective

differences justify differentiation” (p. 55).

Here, it is difficult to see how such equality before the law could hold

the case in either case.

“The Exercise of Power (4) Ministers and public officers at

all levels must exercise the powers conferred on them in

good faith, fairly, for the purpose for which the powers were

conferred, without exceeding the limits of such powers and

not unreasonably” (p. 60).

Here, assuming we are talking about honest ministers, then this aspect

of the rule of law does seem applicable in both cases.

63

Bingham 2010, pp. 37-129.

35

“Human Rights (5) The law must afford adequate protection

of fundamental human rights” (p. 66).

But the notion of human rights is absent in the ancient case and

present only very implicitly in the early modern one.

“Dispute Resolution (6) Means must be provided for

resolving, without prohibitive cost or inordinate delay, bona

fide civil dispute which the parties themselves are unable to

resolve” (6).

Both the early modern and the ancient case appear to incorporate this

notion.

“A Fair Trial (7) Adjudicative procedures provided by the

state should be fair” (p. 90).

Historical evidence appears to show that neither the early modern nor

the ancient instance could satisfy this notion.

“The Rule of Law in the International Legal Order (8) The

rule of law requires compliance by the state with its

obligations in international law as in national law” (p. 110).

Here, the evidence appears to show that in the ancient case this

aspect did not apply whereas in the early modern case, owing to the

international character of the treaty, this aspect did apply.

Now, when we go through the results of this attempt to

understand more fully the nature of the constraints the various rules

and regulations, punishments and penalties that comprised effective

governance in both the ancient and the early modern examples, we

come upon two important points. First, the greatly ambiguous notion of

the rule of law, even when elaborated in detail, does not allow of

sufficient generalization to account for the practices in both the early

modern state and the ancient one. And, second, the notion of law that

36

the polyvalent expression “the rule of law” incorporates requires

elucidation. We will now take up that elucidation in the following subsection.

7.3 Law and the Limits of Political Sovereignties

Unsurprisingly, contemporary philosophers of law disagree about

just what the law is. Looking at one of the major disagreements today

about what law is will bring us to a fuller appreciation here of just what

the limits of political sovereignty come to.

The majority contemporary view on the nature of law in Englishlanguage philosophy of law (also called legal philosophy)vii comes down

from the work of the Oxford philosopher of law, H. L. A. Hart (19071992), especially from his most prominent work, The Concept of Law

(1961) and Law, Liberty and Morality (1963).64 Hart’s most illustrious

student, successor at Oxford, and prolific critic was the American

philosopher of law, Ronald Dworkin (1931-2013) whose most important

works were probably the two books, Law’s Empire (1986) and Justice

for Hedgehogs (2011).65 Hart’s later student and successor at Oxford,

defender, and critic of Dworkin is Joseph Raz (1941 -- ). His most

important works include The Authority of Law (1979), Practical Reason

and Norms (1990 [1975]),66 and The Practice of Value (2003).

In the philosophy of law today it is customary to distinguish

between analytical and critical philosophy of law.67 Roughly speaking,

64

See Hart 1994, Coleman 2001, and Hart 1963. On Hart cf. MacCormick 2004.

See also Dworkin 1978, Dworkin 1985, and Dworkin 2000. On Dworkin cf. Guest

2013.

65

66

See also Raz 1986 and Raz 2009. On Raz cf. Marmor 2011, pp. 60-83.

67

See Finnis 2005 in Honderich 2005, pp. 500-504.

37

analytical legal philosophy treats, among other matters, the definition

of law and of legal concepts, while critical legal philosophy treats, also

among other things, the evaluation of laws and legal systems.viii In

analytical works we find a variety of accounts of the nature of law.

Two of the most recent and distinguished deserve our attention here.

The first, Scott Shapiro’s Legality (2011) is strongly in the tradition of

Hart and Raz, while the second is the final magisterial work of Dworkin

himself, Justice for Hedgehogs (2011).

Roughly, for Shapiro what determines the nature of law is society

and in particular social facts; what specifies those social facts is

empirical description. 68 In contrast, for Dworkin what determines law’s

nature is morality and in particular moral values; and what specifies

social facts is not description but moral evaluation.69 “Dworkin clearly

believes,” his most accomplished commentator writes, “that the

rightness of an interpretation is a matter of the moral evaluation of

actual or imagined facts of legal practice, not a matter of a description

of those facts.”

70

In these terms, of course, the contemporary debate about the

nature of law seems to be a version of the Humean doctrine of a strict

separation between facts and values, here between social facts and

moral values. Thus, on Dworkin’s view “no fact contradicts any

judgment of value. Hume’s principle governs completely. That means

Shapiro’s has been so far less prolific than Dworkin. Besides his major 2011 work

see however his joint collection, Coleman and Shapiro 2004, and his article,

“Authority,” in that collection, pp. 382-439.

68

For an up-to-date bibliography of Dworkin’s extensive writings see Guest 2013, pp.

271-286.

69

70

Guest 2013, p. 58.

38

that social facts have legal meaning only insofar as they are explained

or justified, or nested within judgments of moral value.”

71

There is, however, more than a nuance here that we need to

underline. The distinction between these two views about what

constitutes the nature of law is not between social facts on one side

and moral values on the other. Rather, the disagreement is between

those who hold that only social facts determine the nature of law, and

those who hold that both social facts and moral values determine law’s

nature.

72

This nuance has important consequences. For, “if the positivist is

right [for example, Hart 1961] and the existence and content of legal

systems are ultimately determined by social facts alone, then the only

way to demonstrate conclusively that a person has legal authority or

that one is interpreting legal texts properly is by engaging in

sociological inquiry . . . . [but] if the natural law theorist [for example,

Finnis 1980] is right and the existence and content of legal systems

are ultimately determined by moral facts as well, then it is impossible

to demonstrate conclusively what the law is in any particular case

without engaging in moral inquiry.”

73

We need not here enter into the discussion of just what defines a

legal positivist theorist or a legal natural law theorist before grasping

the major point here. Dworkin and those who follow his views on the

nature of law believe that the law is through and through moral – “law

is a branch of politics, which is a branch of morality.”

71

Loc. Cit.

72

Cf. Shapiro 2011, p. 29.

73

Ibid., pp. 29-30.

74

Guest 2013, p. 58.

74

Shapiro and

39

those who follow his views believe that the nature of law is not

through and through moral.75

In particular, Shapiro holds that “social science cannot tell us

what the nature of law is . . . [because] social scientific theories are

limited . . . being able to study only human groups and hence cannot

provide an account about all possible instances of law.”

76

The only

example he gives, however, of other non-human instances of law are

those he takes from, of all things, science fiction.

77

On these rather shaky grounds Shapiro goes on to reject the view

of many other legal theorists who argue that analytical legal

philosophers in their attempts to understand the nature of law must

consult the social sciences, since part of the tasks of the social

sciences is to study social institutions, and law is certainly at least

partly a social institution.

Accordingly, Shapiro tries to explain away Hart’s explicit

statement that his own work in legal theory was “an exercise in

descriptive sociology”

78

in order to claim Hart as effectively holding

his own views, he writes, “My own view is that Hart was right with

respect to the concept of law.”

79

But that can be the case only on

appeal to his own revisionist interpretation of what Hart himself

actually wrote. For Shapiro’s interpretation appears to stand on no

steadier evidential bases than on science fiction ones.

The matter here in fact is more general than may at first appear. The issue is how

to account for social dependence of values without falling into cultural relativism. Cf.

Raz 2003, pp. 15-36 and 121-156.

75

76

Shapiro 2011, p. 407.

77

Ibid.

78

Hart 1961, p. vi; cited in Shapiro 2011, p. 406.

79

Ibid.

40

In the end, Shapiro comes back to a more stable understanding of

the nature of the law. Regardless of the difficult matter of the extent to

which the nature of the law is independent or not in some strong

senses of what social facts are taken to be, Shapiro insists “that it is

part of our concept of law that groups can have legal systems provided

they are more or less rational agents and have the ability to follow

rules.”

80

And legal systems here are understood as fundamentally

certain systems of rules.

Dworkin disagrees. The nature of law, he argues is not to be

understood as a function of systems of rules of whatever kind. For law

consists of much more than rules arranged in some systematic order.81

To see why Dworkin thinks this, we need to note above all his

programmatic objective to replace what he calls the ordinary, orthodox

picture of law and morality forming two separate systems of norms

with his own, reformed picture of law and morality forming but one.82

The orthodox belief, Dworkin thinks, is that law “belongs to

communities, that it is made by people, that it is contingent.”

Moreover, many philosophers, whether “conventionalists or relativists

or skeptics of some other form” think that, just like law, morality too

belongs to communities, is made by people, and is contingent.83 In

short, although there may be questions about how these two systems

interact, on an orthodox account systems comprise very similar

although not identical kinds of norms.

Ibid., p. 407. Note, however, several questions in Marmor 2013 about the

appropriateness of conceptual analysis only for the explanation of the nature of law.

80

81

Dworkin 1978, chapter one.

82

See McCormick 2012, pp. 99-107.

83

Dworkin 2011, p. 401.

41

Dworkin rejects the orthodow view. He thinks law and morality,

although similar in being collections of norms, are fundamentally

dissimilar in collecting very different kinds of norms. And this nonidentity of kinds of norms is perhaps the most important feature that

makes the systems of law and morality themselves non-identical.

Thus, morality, unlike law, does not belong to a community,

because morality “consists of a set of standards or norms that have

imperative force for everyone.”

84

Further, morality, unlike law, “is not

made by anyone (except, on some views, a god). . . .”

85

Still more,

morality, unlike law, “is not contingent on any human decision or

practice.”

86

But if Dworkin is right, then he must answer satisfactorily a

central and difficult question. For if indeed there are two systems of

very different kinds of norms, how exactly are they related?

By way of response Dworkin highlights two approaches to this

question. One he calls, without qualification,87 the “legal positivism”

approach, the other the “legal intrepretivism” approach. The first,

presumably, is that of Hart and his followers including Shapiro, who

hold for a complete independence between the two systems of norms.

84

Ibid., p. 400.

85

Loc. cit.

86

Loc. cit.

Here, unlike Shapiro 2011, pp. 269-277, Dworkin does not distinguish between

inclusive legal positivism (the view that social facts ultimately determine legal facts)

and exclusive legal positivism (the view that social facts alone determine legal

facts). More explicitly, exclusive legal positivism holds that “not only do social facts

determine the content of the law at the highest level, but they do so at every point in

the chain of validity. Under no conditions may the truth of a legal proposition depend

on the existence of a moral fact” (p. 269). Cf. Waluchow 1994, Himma 2004, and

Marmor 2004.

87

42

This is the orthodox and indeed majority position. And the second is

his own, the reformed and minority position, which denies that the two

systems are completely independent.

On the legal positivist account, “what the law is depends only on

historical matters of fact: it depends finally on what the community in

question, as a matter of custom and practice, accepts as law.”

88

By

contrast, on the legal interpretivist account, what the law is depends

“not only [on] the specific rules enacted in accordance with the

community’s accepted practices but also [on] the principles that

provide the best moral justification for those enacted rules.”

89

What stands behind the interpretivist account is a particular

understanding of the polyvalence of Hart’s expression, “the concept of

law.” Dworkin thinks that there this expression confounds three

different senses of “the law.” There is what he calls the sociological

sense of the law “as when we say that law began in primitive

societies,” what he calls the aspirational sense “as when we celebrate

the rule of law,” and what he calls the doctrinal sense that “we use to

report what the law is on some subject.

90

Although both positivism and interpretivism both consider the

concept of the law in its doctrinal sense, each takes the concept of

law in a different way. For the positivist, the concept of the law is a

criterial concept, that is, a concept that satisfies “the tests of pedigree

that lawyers . . . share for identifying true propositions of doctrinal

law.” For the interpretivist, the concept of law is an interpretive

concept, that is, a concept that “treats lawyers’ claims about what the

88

Ibid., p. 401.

89

Ibid., p. 402.

90

Loc. cit.

43

law holds or requires on some matter as conclusions of an interpretive

argument. . . .”

91

Now, this interpretivist picture of the two systems of law and

morality as collections of very different kinds of norms which Dworkin

first sketched out in 1977 is, he went on in 2011 to argue surprisingly,

fatally flawed. “The two-systems picture . . . faces an apparently

insoluble problem: it poses a question that cannot be answered other

than by assuming an answer from the start.”

92

How so?

“Once we take law and morality to compose separate systems of

norms,” he writes in 2011, “there is no neutral standpoint from which

the connections between these supposedly separate systems can be

adjudicated.”

93

That is, we cannot adjudicate in any neutral way any

answer to the question whether one view or another is the more

accurate. For that question itself – “Which is the more accurate view of

the law, the positivist or the interpretivist?” – raises the more

fundamental question – “But what kind of a question is that, a legal one

or a moral one?” Dworkin goes on to demonstrate that answering the

second question either way turns out necessarily to be viciously and

not virtuously circular.

94

Still, once we concede that law is not a criterial but an

interpretive concept, a notion Dworkin explores at some length,95 then

Dworkin believes there is a persuasive approach to handling the

circularity issue if not a finally demonstrative one. That approach

91

Loc. cit.

92

Dworkin 2011, p. 403.

93

Ibid., pp. 402-403.

94

Ibid., p. 403.

95

Ibid, pp. 157-158.

44

involves spelling out just how we come to understand what an

interpretive concept like the concept of law comprises.

We begin an analysis of the concept of law then in a quite

particular way. We begin, he writes, “by identifying the political,

commercial, and social practices in which the concept figures. . . . We

[go on to] construct a conception of law . . . by finding a justification of

those practices in a larger integrated network of political value. We

construct a theory of law, that is, in the same way that we construct a

theory of other political values – of equality, liberty, and democracy.

[And he adds:] Any theory of law, understood in that interpretive way,

will inevitably be controversial, just as those latter theories are.”

96

This is the approach to the concept of law as an interpretive kind

of concept rather than as a criterial kind that brings Dworkin to his

conclusion. Law is not to be treated as separated from political

morality, as in the orthodox two-system picture. Rather, in the

reformed one-system picture, law is to be “treated as a part of political

morality.”

97

More fundamentally, on Dworkin’s interpretivist account of law,

law has its proper place in what he calls “a tree structure.” Thus, law

is a branch of political morality.98 Political morality itself branches from

personal “morality” in Dworkin’s special sense of how we should act

towards others. And personal morality branches from what Dworkin

calls “ethics” in his special sense of how we should live.99

96

Ibid., pp. 404-405.

97

Ibid., p. 405.

On Dworkin’s complicated views on the relations between law and morality see

Marmor 2011, “Is Law Determined by Morality,” pp. 84-108.

98

Ibid., pp. 13-15 and 191; see Guest 2013, pp. 160-163. Still other “branches” of

Dworkin’s tree structure can be glimpsed in an excerpt in The New York Review of

99

45

What comes clear in this opposition between a legal positivist

criterial concept of law and a legal interpretivist conception of law is

the fundamental limiting role of law on political sovereignties. No

political sovereign, whether in a Westphalian system or in a

Mycenaean system, can dispense with the absolutely fundamental role

of rules. For without rules no system of government is possible.

But rules make up a collection. And whether we conceive of that

collection in general as something so historically developed as “the

rule of law” or as something much more ancient as say “the rules of

the leader” whether a wanax or a king, these collections of governance

rules are of their very nature constraints on political sovereignty.

In most of the much later European cases they are constraints

imposed by social communities on their rulers whether chosen or not.