File

advertisement

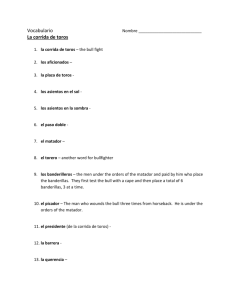

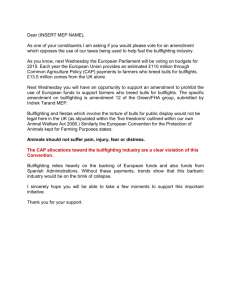

Spanish Bullfighting: The Romance, the Drama and the Traditional Recipes by Justin Roberts Recently, the northeastern Spanish region of Catalonia (or Catalunya) voted to ban bullfighting; which consequently, provoked me to write an article. Since moving to Spain in 2005, I have attempted to understand the “corrida de toros” – the bullfight. I have tried to learn as much as possible, both the pro and con; and yes, I confess I have attended quite a few corridas. Portugal has its own bullfighting traditions, as does France and Latin America. There is even a type of bullfight on the Zanzibari island of Pemba, off the east coast of Africa – a relic of Portuguese colonialism. However, I’m only familiar with the way it is done in Spain. In the part of Spain where I live, the “corrida” is at the center of a complicated web; however this is definitely not true for all of Spain, as exemplified in Catalonia. The heartland of bullfighting is the warm southern region of Andalusia. Many people in my town of Jerez are connected to the bullring in some way, and it’s hard not to take an interest. Some of the grand old families who once owned sherry bodegas rear the bulls and horses used in the ring at their large estates and some even enter the ring itself. In Jerez, there was a time when you were just as likely to see the name “Domecq” on a sherry bottle as on the “cartel” - the iconic poster used to advertise a bullfight. The highlight of the year in Jerez, and many other towns and cities in Spain, is the annual “feria” – the fair. A feria without a bullfight is almost unheard of in the south. They go hand in hand. The larger towns and cities will usually have a bullfights on most afternoons of the fair, and in some cases, such as Sevilla, the bullfights are an attraction in their own right. Many places consider the bullfights an important part of their cultural activities. There is a very obvious dark side to bullfighting – the cruelty – which some people in Spain, even in the traditional heartlands of bullfighting in the south, are very much against. In this post, I will steer clear of the rights and wrongs as much as I can, but I hope that we get an interesting discussion in the comments section below. I will try simply to describe what I have seen, learned and experienced. Where did it all start? Some try to link Spanish bullfighting to the Roman circus and even further back to Minoan bull-leaping but this is probably stretching it a bit. What I think it really boiled down to was battle and horses. In the not so distant past the aristocracy liked to fight and always from back of a horse. If rider and steed were not a quick and nimble combination the chances were they both died on the battlefield. To practice, Spanish nobles clubbed together (the clubs still exist today, in Seville and Ronda for example) to organize competitions amongst themselves, usually in their town’s main square. There was nothing unusual in this; competitions like these have been around for as long as people have ridden horses. It’s just that at some point bulls were thrown into the mix, which definitely was a departure. A loose, and slightly grumpy, bull was an excellent way to test horse and rider under pressure. The horse had to remain surefooted and his noble rider calm as they showed off their bravery and skill by riding circles around the bull, inches away from its horns. A safety net was provided: Servants were on standby on the sides to distract the bull when things got too hot – or went wrong. No doubt the servants waved around their hats or capes to catch the bull’s attention when necessary. Sometime in the early 1700s King Felipe V banned nobles from fighting bulls. Apparently Felipe disapproved and thought it set a bad example to the masses. The Pope agreed. It is more likely too many of Felipe’s nobles were getting killed. It was at the time of this ban that the men on the ground started to become the main attraction. Waving around their cape developed eventually into a system of stylized passes, each with its own name, like the “veronica“; traditions were born and bullfighting gained a life of its own. In time, however fighting bulls from the back of a horse did return, which means there are two broad forms of bullfighting in Spain. The “corrida de toros“, where the bull is fought by men on their feet and the “corrida de rejones” where it is done from a horse. The majority of bullfights, by far, are “corridas de toros”. There are also minor variations to both forms, but generally they follow the same format. So what happens at a bullfight? Once you have squeezed into your little spot – most rings were built when people were much smaller – the first thing you will see is the “paseillo.” The bullfighters, their teams and the officials participating parade into the ring. They enter opposite the president’s box and walk towards it, salute and then do a turn around the ring. A good picture of the paseillo can be seen here. A fight is always presided over by an important person, often the local mayor, and the president’s box is always high up and in the shade, the western side of the ring as bullfights always take place in the afternoon. The crowd at a bullfight is usually a mixed bunch, especially during the feria: rich, poor, old people, young people, locals and tourists. The more famous bullfighters have fan clubs, “peñas”, and often very loyal followers who pay big sums to follow them around the country during the season. There are also more general bullfighting clubs called, peñas taurinas, some of which are located in very unusual locations, such as London. These groups usually have season tickets at the ring, gather together in groups, are very vocal and noisy, and decorate their space by draping flags etc over the railings in their section of the ring. A bullfight crowd is normally a good-natured and nosy bunch, luke-warm wine squirted from a leather bladder is often shared with strangers and there is always barracking and conversation. There is no traditional item to drink or eat at a bullfight, but ice-cold beer is refreshing if sitting on the sunny side of the ring and almost everyone will be shelling and eating “pipas” – salt-roasted sunflower seeds. Bullfighting is full of superstition, so one thing you must never do is wear yellow in the crowd – this can only mean bad luck. Normally there are six bulls and three bullfighters involved in a corrida, but sometimes only two bullfighters “mano a mano.” The generic term for a bullfighter is a “torero” I have see “toreador” used in English, but never in Spanish – perhaps that is an old word. The toreros allowed to kill the bull are called “matador” and if they fight the bull from a horse “rejoneador“. Usually the least experienced matador or rejoneador fights the first bull, the next most experienced fights the 2nd and the most experienced challenges the 3rd bull; this sequence is repeated again for the remaining 3 bulls. In a mano a mano, it is one torero at a time until all six bulls have been fought. Each bull is always given a name, which is displayed before the fight along with the bull’s weight and the breeder’s details. Some bulls become notorious in Spain. Ask most Spaniards what the name “Avispado” means to them, and they will tell you it is the bull which killed the famous bullfighter Paquirri. Breeders can also become famous for their bulls, like the legendary “Miura” bulls, which are considered unpredictable, dangerous and difficult to fight. A bullfight is divided up into three stages called “tercios” and a trumpet signals the beginning of each stage. The first stage is the “tercio de varas.” Vara is Spanish for lance – http://catavino.net/spanish-bullfighting-the-romance-the-drama-and-the-traditional-recipes/ in this case a long wooden pole with a small blade at the business end. The bull is released from a gate opposite the president’s box. Using their large gold and magenta capes, or “capotes“, the matador and his team will get the bull to do a few passes so it can be assessed: How it charges, where it likes to hang out in the ring (it’s “querencia“) and how it lifts its head through a charge. If the bull is a complete dud, or lame, it will be sent off and another one bought in. After this, two picadors, each holding a lance, enter the ring. The picadors are mounted on sturdy little horses, which are heavily padded and blindfolded. The picadors’ job, on the matador’s instructions, is to get the lance blade into exactly the right spot in the mound of muscle at the top of the bull’s neck. This is to “correct” the way the bull holds and lifts its head and to “straighten” its charge. I’ve also been told the blood-letting involved lowers the bull’s blood-pressure and stops it from having a heart-attack, but I’m not sure about that. The bull is encouraged to charge the picador’s horse and as it gets near the lance is lowered and the blade at its end goes in. The horse invariably gets shoved around quite a bit by the bull, even turned over onto the ground sometimes. There are a set number of times the bull is supposed to be lanced but if the crowd feel this is being overdone they whistle and jeer – the bull would be too weak to put on a good show and things would be too easy for the torero. Until the late 1920s the picadors’ horses were unprotected and many were gored and killed. In those days the picador was a much more important part of the bullfight, as he had to show off his skill of lancing the bull while keeping his horse out of harms way. I guess this was stopped because too many horses were being lost in the ring. In the corrida de rejones this part of the fight is modified, the rejoneador lances the bull from his horse, using a much shorter lance than the picador’s lance and wrapped around the end is a small flag, which unfurls when the bull has been stabbed. The second stage is the “tercio de banderillas.” Banderilla means little flag, and the “flag” in this case is a wooden stick, about two feet long, with a metal barb at one end. Most of the stick is decorated with coloured paper, usually significant: Red and yellow for Spain, or the local town’s colours – in Jerez that means blue and white. Sometimes the matador places the three pairs of banderillas himself but most often there will be one or more “banderilleros” to do this for him. The banderillero has to get these banderillas into the muscular area at the top of the bull’s neck. To do this properly the banderillero should put himself in danger by getting his chest to pass close to or even between the horns. There are different techniques for placing the banderillas and the crowd will be watching closely to see how this is done. Sometimes with a banderilla in each hand, other times with both in one hand. In the corrida de rejones,banderillas are placed one at at time from the horse’s back. The second stage ends when the trumpet sounds for the third and final stage to start. The “tercio de muerte”: The third stage of death. The matador dedicates the bull to someone, usually someone important, by throwing his cap up to them, or to the crowd in which case he places the cap in the centre of the ring. This time the matador fights the bull with a small red cape, the “muleta”, in one hand and a sword in the other. The matador works the bull trying to join passes together into sequences. The matador is studied carefully by the crowd for his technique and if they like what they see he will be encouraged with shouts of “ole”; if things are going particularly well the band will strike up a “pasodoble taurino”. The corrida de rejones equivalent is some fancy riding around the bull, the rejoneador sometimes leaning over from his horse and touching the bull’s back. http://catavino.net/spanish-bullfighting-the-romance-the-drama-and-the-traditional-recipes/ After the first pass with his muleta the matador must kill the bull within 15 minutes. At 10 minutes of working the bull the matador will be given a “reminder” by trumpet. Shortly after this the matador swaps swords, the one used to work the bull being a lighter version of the one used to kill it. The matador lines up with the bull, gets it to charge at him, and leaning into the charge he plunges the sword deep into the bull’s shoulders, the “estocada”, the kill. In acorrida de rejones, the rejoneador will usually kill the bull from his horse, but some of rejoneadores prefer to dismount and perform the estocada on their feet. A “good” kill is when the sword goes in down to the hilt, cutting the heart or aorta, in which case the bull dies quickly, usually staggering for a bit and then keeling over dead. A “bad kill is when the matador strikes bone – shoulder blade or vertebra – and the sword goes in at a bad angle or not at all. The matador must have another go, or even several tries before the the bull is killed. This can be messy and unpleasant. The crown normally shows their disapproval by whistling and jeering. A “bad” kill can spoil a fight which has been perfect in every other respect. In very rare instances, when the bull is considered to have put up a particularly brave and noble fight, it is allowed to live, a “toro indultado”. In this case the matador goes through the motions of the estocada, sometimes using a banderilla as a pretend-sword and the bull is herded out the ring and gets to live out its days on a pasture somewhere contributing its brave genes to the pool. If the matador is killed by the bull, then one of the remaining matadors has to step into his shoes and finish the bull off. An unenviable task because bullfighting superstition says a matador who does this will soon be killed in the ring himself. Matadors continued to get gored don’t often die any more, mainly because of better medical care and also penicillin. The bull is dead. Depending on how well the whole bullfight went the matador might get an award. The matador can get one ear (which is cut off and presented to him in the ring) for a good fight, two ears for a better fight and for the perfect fight the bull’s ears and tail will be presented. They used to award hooves too, but not anymore. Once this is done the bull is tied up to a team of mules and dragged out of the ring. This is where I should say how important the crowd is in a bullfight. The president of the fight makes all the decisions, but is always influenced by the crowd. The crowd might plead for something from the president by cheering and waving something (traditionally a white kerchief but anything goes now) at the presidents box. They might plead for the first ear, and once that is granted shouting “otra…otra…otra”, plead for the next ear and possibly the tail. Equally the crowd will make their disapproval clear by loud whistling, jeering and booing. If a new bull is not “brave” enough, too tame (“manso“), the crowd will whistle and jeer until the president orders it off. The president signals by hanging different coloured cloths over his balustrade. A single green one gets a bad bull taken off; one white cloth an ear, two white cloths two ears; a red one and the bull is “indultado” and not killed. If the matador has been awarded anything, he is allowed to do a circuit of the ring to thank the crowd. Usually people throw down flowers into the ring, or hats for him to touch and then throw back to them. I’ve even seen mobile phones thrown down. The greatest honour for a matador after a particularly good day is to be carried around the ring and out the main doors on the shoulders of others, but this is unusual. The day after a bullfight the meat, “carne de toro bravo“, will normally be available at the local market, and sometimes at certain restaurants shortly after the fight. I have never tried it, but I’m told it has a particular taste – probably all the bitter adrenalin. One typical dish is “rabo de toro“, the bull’s tail stewed, often with wine (or Oloroso in the case of Jerez). http://catavino.net/spanish-bullfighting-the-romance-the-drama-and-the-traditional-recipes/ How does one become a matador? Well it helps to be a man for a start. There are women matadors, but they have a pretty rum time of it. Bullfighting is very “traditional” and many supporters do not accept women, so they don’t draw the crowds. To become a bullfighter you have to join a bullfighting school, normally from a very young age. There are bullfights for novices (novilleros), called novilladas, where bulls not up to scratch for a proper corrida are fought. These novilladas can be hit or miss affairs: The bulls not great, so the performance probably lacklustre, but occasionally a better than expected bull combines with a novillero out to prove himself and the results are spectacular. If a novillero is considered good enough to become a matador (competition is fierce and most don’t make it) he will be invited to fight in a proper corrida. At current matador will sponsor the novillero and at the corrida a little ceremony of initiation takes place: The more experienced sponsor matador gives his sword and muleta to the novillero and the novillero gives his capote to the sponsor, all witnessed by a third matador. An embrace, a slap on the back and the novillero has become a matador de toros. This ceremony is called the “alternativa”, and every matador can trace back his “lineage”, through his sponsor, to his sponsor’s sponsor, going back through the ages. Is bullfighting a sport? Some say bullfighting is a sport. Others say it is an art form. In Spain the bullfights are reported in the culture section of the newspapers – next to the book reviews. However there is scoreboard in bullfighting – the “escalafon” – where the number of ears and tails a bullfighter has been awarded through the season are chalked up, so you could say it is a kind of sport. But is it art? Bullfighting certainly has aspects of an art form. The stylized passes with the cape can be expressed in a certain way, a bit like expressing something through dance. Some people find the passes beautiful to look at and ballet-like. Others simply see a self-important ponce prancing about in tight pants. The bullfight certainly carries a lot of cultural baggage, like the “pasodobles” you will hear played at bullfights. There is plainly a cross pollination between Flamenco culture and bullfighting culture. In the south of Spain especially, the connection with the spring fairs – the Ferias is obvious. When one thinks of Spanish culture, it’s hard not to include bullfighting in that mental picture. Finally, should it stay or should it go? Is bullfighting a part of Spanish culture which should be preserved or is it a barbaric tradition well past its sellby date? What do you think? Saludos ~Justin Roberts http://catavino.net/spanish-bullfighting-the-romance-the-drama-and-the-traditional-recipes/