Bonnie-Cullen-Cinderella-in-the-Hands-of

advertisement

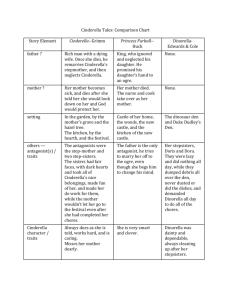

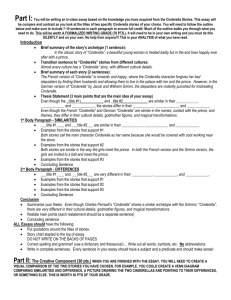

My summary of Bonnie Cullen’s article will serve as an example for how I want your second article summary to go. I’ve formatted it here as you may want to do for your pecha-kucha presentation: chunks of texts that take about 20 seconds to read, to correspond to the slides that will be moving automatically at that interval. 1. Cullen begins with Disney’s 1950 film. Though, as we know from our reading, “Cinderella” existed in lots of versions, Disney’s film has essentially eclipsed them. But Cullen looks back a little earlier, and argues that in fact it was the Victorians who selected this one version of Cinderella from among the many options. By the early twentieth century a fairly standard form of “Cinderella” had emerged in most English editions—an adaptation of the French tale written by Charles Perrault and published in 1698. But why would this be the case? 2. In Perrault’s version, Cinderella is “generous, long-suffering, charming and goodhumored; the ideal bride, from the gentleman’s perspective.” The fairy Godmother plays the dominant role, and she’s the one with all the power. The moral he appends has some irony to it: depend on good looks over beauty, but to succeed you really just need a fairy godmother. 3. But the Countess D’Aulnay’s version was the first to be published, and the more popular in the 18th century. In her version, Cinderella and her sisters are abandoned, but Cinderella comes up with clever plans to save them all (even though her sisters plot against her). With a godmother’s help she finds some great clothes, goes to the ball, and loses a shoe. She goes back to retrieve it, but won’t marry the prince until he restores her kingdom. In other word’s, she’s the hero and the marriage is secondary. 4. These versions of the story would have had to compete with the Grimms’ version, which was first published in English in 1826. Their version of Cinderella emphasizes mourning and revenge, and it’s still the Godmother who has the power. All this proved a bit much for the English, who cleaned up the tale in later versions. 5. In the nineteenth century, Cullen argues, Perrault’s story began to overtake D’Aulnay’s, and still beat the Grimms’. As evidence for this, she counts the number of editions of each work that were produced during the period. 6. Cullen’s research is archival: she spent time at the British Library and the Victoria and Albert Museum’s National Art Library, which are both in London. Much of her argument focuses on illustrations. Though the story we know now had only one illustration (Cinderella fleeing the ball and leaving her slipper behind), by the 1830s there was fairly established set of images: Cinderella by the hearth; Cinderella doing the sisters’ hair; the godmother’s appearance; the ball and/or Cinderella running from the prince; the slipper trial, and marriage. All of these connect far more to Perrault’s version of the story than to the D’Aulnay’s. 7. She’s interested not just in which scenes get illustrated, but also in the details of the illustrations. Today we call them the “ugly stepsisters.” That seems to have been an English twist on the tale. A marriage becomes a focus, Cinderella’s good looks become a textual focus and the stepsisters get uglier in contrast. 8. Cullen links her conclusions about Cinderella to Victorian culture more broadly. She reads illustrations of the stepsisters in terms of Victorian “sciences” like phrenology and physiognomy (face reading), and she cites historian Linda Nead, who studies visual portrayals of Victorian women. Women were gradually gaining more rights: by 1865 women could own property, and they could vote by 1919. 9. But versions of “Cinderella” often worked against these changes. Cullen mentions Cruikshank’s version, which turns Cinderella into a story about temperance, and she’s really interested in Dickens’s response. As you saw in his story, when women turn to politics “nobody dares to love them.” 10. Perrault’s version of “Cinderella” became vehicle for the Victorians’ conservative ideas about femininity. When Disney made his film in 1950 women were again being urged back into the home, as the men returned from World War II. If that’s the version we encounter most often, we would do well to remember its roots.