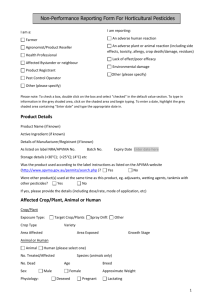

Hills Orchard Improvement Group Inc

advertisement