As the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee considers

advertisement

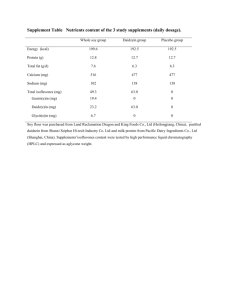

Soyfoods Association of North America 1050 17th Street, N.W. • Suite 600 • Washington, DC 20036 • USA September 25, 2013 Richard Olson, M.D., M.P.H. Co-Exec Secretary of Dietary Guidelines DHHS/Office of Disease Prevention & Health Promotion 1101 Wootton Parkway, Suite LL100 Rockville, MD 20852 Dear Dr. Olson: The Soyfoods Association of North America (SANA), a trade association of soy farmers, processors, soyfoods manufacturers, and soyfoods educators, appreciates the efforts of the US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) in encouraging Americans to consume a healthful plant-based diet and to adopt eating behaviors that can be sustained. It is evident the DHHS and USDA Dietary Guidelines for Americans has played a vital role in revising the nutritional standards of the federal food assistance programs and nutrition education programs to promote the public’s health and wellbeing. Because these guidelines are the cornerstone of all food and nutrition policy and communication, we encourage DHHS and USDA to continue pursuit of a plant-based diet and provide culturally relevant dietary patterns that allow more Americans the chance to adopt the Dietary Guidelines as their way of eating. SANA members value the extensive review of the scientific research on nutrition by the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC), and we have submitted a review of research that fills some of the gaps identified in the 2010 report (submitted July 29, 2013, comment No. 41). In the following comments, we offer some additional research and reiterate the important role of vegetarian diet including soyfoods in meeting cultural food preferences, managing optimal weight and reducing the risk of heart disease, possibly lowering the risk of breast cancer when consumed early in life, and providing a variety of high quality protein soyfoods for all ages. Preserving Cultural Patterns and Inclusion of a Wide Variety of Foods Important to Adoption of Dietary Guidelines The origins of soyfoods date back to the 1500s in China1,2 and 1665 in Europe3 when referring to soymilk as part of the process for making tofu. It was Founding Father Benjamin Franklin who introduced soybeans and the first recipe for tofu to America in 1770.4 The world’s earliest 1 Su Ping. 1500. Ode to tofu. Quoted by Wai, 1964, p. 91-92. Shurtleff, W and Aoyagi, A. Comprehensive History of Soy. Soy Info Center, http://www.soyinfocenter.com/HSS/soymilk1.php. Accessed website August 13, 2013. 3 Navarrete, Domingo Fernández de. 1665. A Collection of Voyages and Travels. Published by the author, London. See p. 251-52, Chap. 13 4 Soyfoods Are Part of America’s History. Soyfoods Association of north America. July 3, 2013. Accessible on website, http://www.soyfoods.org/press-releases/soyfoods-are-part-of-americas-history. 2 reference to soymilk as a drink appeared in China in 18665 and in the United States in 1896 in the American Journal of Pharmacy.6 In 1913, the first U.S. patent for soymilk (No. 1,064,841) was granted and by 1917, soymilk was being produced commercially. 7 The emergence of soybased meat alternatives tracked the demand from 7th Day Adventists in the 1930s.8 Soyfoods have gained popularity among young adults ages 18-34, the growing Asian and Latino population in the United States, those who avoid animal products, and health-conscious adults and their families.9,10 Soyfood consumption begins early in life for many. A study in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition indicates that soyfoods are consumed by 90 percent of healthy Asian children, with 95 percent of these children consuming soyfoods before 18 months of age.11 The population of Asian Americans is the fastest-growing minority group, with a population increase of 43.3 percent from 2000 to 2010. Asian populations include Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Filipino, Vietnamese, Pacific Islander, or Native Hawaiian, many of whom have consumed soyfoods for years. The popularity of soyfoods remains high among the Asian Americans, but now reaches a broader audience. The 2010 U.S. Census data below show considerable growth in all minority groups that have diverse dietary preferences and cultural needs. 2010 Census Demographics Race White African American Some Other Race Asian Two or More Races American Indian Pacific Islander Percent of Total Population 72.4 12.6 6.2 4.8 2.9 0.9 0.2 Number 223,736,465 38,929,319 19,107,368 14,674,252 9,009,073 2,932,248 540,013 Change from 2000-2010 Percent 5.7 12.3 24.4 43.3 32.0 18.4 35.4 Data from the US Census 2010, available at www.census.gov/2010census Champion, Paul. 1866. On the production of tofu in China and Japan. Bulletin de al Societe d’Acclimation 13(6):562-65. June. 6 Trimble, Henry. 1896. Recent literature on the soja bean. American J. of Pharmacy 68:309-13. June. 7 Piper, C.V.; Morse, W.J. 1916. The soy bean with special reference to its utilization for oil, cake and other products. U.S.D.A. Bulletin No. 439. Dec. 22. p. 9; Horvath, A.A. 1927. The soybean as human food. Chinese Government Bureau of Economic Information, Booklet Series, No. 3. p. 47. 8 William Shurtleff and Akiko Aoyagi. Worthington Foods Work with Soyfoods, Soy Info Center. 2004. Visited 8/13/2013, http://www.soyinfocenter.com/HSS/worthington_foods.php. 9 Bloom, B. Meat Alternatives – US. Mintel Corporation. June 2013. Available on website: http://store.mintel.com/meat-alternatives-us-june-2013. 10 Mintel Corporation. Soy Food and Beverages – US. March 2011. Available on website: http://store.mintel.com/soy-food-and-beverages-us-march-2011. 11 Quak SH, Tan SP. Use of soy-protein formulas and soyfood for feeding infants and children in Asia. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68:1444S-1446S 5 1050 17th Street, N.W. • Suite 600 • Washington, DC 20036 • USA 2 There is also an increase of individuals identifying themselves as vegan, vegetarian, or flexitarian, who regularly incorporate soyfoods into their diets. To accommodate these preferences, many schools are offering vegetarian offerings daily or regularly. Forty-two percent of Americans consume soyfoods or soy beverages once a month or more, compared to 30 percent back in 2006. The gain appears to be from those who consume soy once a week or more (19 percent in 2006 to 28 percent in 2013). Conversely, 27 percent indicate that they never consume soy, which has decreased steadily since 2006 (then at 43 percent), according to the United Soybean Board’s 20th annual Consumer Attitudes about Nutrition.12 This 2013 consumer survey found 47 percent of consumers, up from 31 percent in 2010, seek out products specifically because they contain soy, and approximately 26 percent are aware of specific health benefits of soy in their diet. Soymilk remains the most frequently consumed soyfood, followed by edamame and veggie burgers. Tofu follows in fourth place. Besides these four examples of popular soyfoods, consumers today enjoy soy nuts, soy nut butter, cultured soymilk and frozen soymilk, soy-based cheeses, and a large variety of meat alternatives and nutrition bars made with soy protein. The 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans includes several representative dietary patterns that illustrated the diverse ways to follow a healthy eating pattern, including vegetarian and vegan. As an example of more traditional Asian diets, the 2010 Dietary Guidelines recognized the Japanese and Okinawan dietary patterns that are associated with lower risks of coronary heart disease (CHD). Detailed information about exact foods in these cultural patterns is limited; but soyfoods, such as tempeh, miso, tofu, and natto are a daily fare in these and other Asian countries. Because of the regular availability of soyfoods in supermarkets, schools, restaurants, and worksite food service operations, consumers of all ages may be more likely to follow the 2010 Dietary Guidelines highlighting plant-based foods. The 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee should incorporate more of these cultural patterns and soyfood options throughout the report and on lists of Sources for Specific Nutrients. Adopting a Plant-Based Diet Does Not Sacrifice Nutrient Intake The vegetarian diet in particular has been shown to support health and reduce risk of diabetes, CHD, and additional chronic diseases.13,14,15,16 The 2010 Dietary Guidelines included a sample Lacto-Ovo Vegetarian Adaptation of the USDA Food Patterns in Appendix 8 and a Vegan Adaptation of USDA Food Patterns in Appendix 9. Soyfoods, along with nuts, seeds, and beans/peas, provided the primary sources of protein, but only soy protein has the protein quality equivalent, as measured by Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) to proteins from animal and animal derived products such as milk. Based on Appendix E-3.3 from the report of the 2010 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, the average daily nutrient content of vegetarian diets compared to the USDA base pattern had 9 to 13 grams more fiber, 23 12 United Soybean Board. Consumer Attitudes about Nutrition. July 2013. Soy Connection. Accessed 8/13/2013, www.soyconnection.com/sites/default/files/Soy_Connection_Consumer_Attitudes.pdf. 13 Barnard ND, Cohen J, Jenkins DJ et al. A low-fat vegan diet and a conventional diabetes diet in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a randomized, controlled, 74-wk clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(5):1588S-1596S. 14 Craig WJ. Position of the American Dietetic Association: Vegetarian diets. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:126-82. 15 Craig WJ. Health effects of vegan diets. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(5):16275-335. 16 McEvoy CT. Vegetarian diets, low-meat diets and health: A review. Public Health Nutr. 2012;3:1-8. 1050 17th Street, N.W. • Suite 600 • Washington, DC 20036 • USA 3 to 43 percent more potassium, 100 grams more calcium, due to fortified soy products in meat and bean group and fortified vegan milks. 17 The 2009 position statement by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics on Vegetarian Diets included reviews of the key nutrients of concern for vegetarians including protein, n-3 fatty acids, iron, zinc, iodine, calcium, and Vitamins B-12 and D.18 The position concluded that wellplanned vegetarian diets are healthful, nutritionally adequate, and may provide healthful benefits in the prevention and treatment of certain diseases. A review19 of the healthfulness of vegan diets reports these diets are higher in fiber, magnesium, folic acid, vitamin C and E, iron and phytochemicals, while being lowerin calories, saturated fat, cholesterol, vitamin D, zinc, calcium, and B12 than traditional diets containing animal and animal derived foods. To fill these gaps, Craig recommends consumption of zinc rich foods and foods fortified with B12, Calcium, Vitamin D. Chart 4 presents the nutrient content of many soyfoods that can fill these nutrient shortfalls. Eating patterns with soyfoods are nutrient dense. Specifically, soyfoods in different proportions of a plant-based diet can be incorporated into the defined food groups, specifically MyPlate included calcium-fortified soymilk in the Dairy Group and multiple soyfoods in the Protein Group. Soyfoods also provide adequate quantities of the nutrients of concern identified in the 2010 Dietary Guidelines20 MyPlate included calcium fortified soymilk in the Dairy Group and multiple soyfoods in the Protein Group. The presence of all essential amino acids in soy protein makes it a complete protein and differentiates it from other plant proteins. In general, soyfoods also contain fewer calories than animal derived choices within the – dairy, protein, and/or vegetables. Therefore, the nutrient density and high protein quality of soyfoods is an asset. Table 1 and 2, taken from Guertin’s article with permission, demonstrates requirements for nutrients of concern can be met with plant-based diets including soyfoods. The nutrient analysis of menus planned with progressive amounts of plant protein from 25-75 percent demonstrates that potassium requirements could be met at the 50 percent and 75 percent level of substitution. As legumes (soy-based foods) were substituted for meat, saturated fat and cholesterol declined significantly, while dietary fiber and folic acid increased. Increases in calcium paralleled additions of tofu, which uses calcium sulfate to coagulate the protein in soymilk.21 Vitamin B12 and zinc decrease in the plant-based menus, although all menus were sufficient in these nutrients. All menus fell short in Vitamin E which the 2005 and 2010 DGAC analyses also found for general and plant-based versions of MyPyramid patterns.22,23 17 US Department of Health and Human Services, US Department of Agriculture. 2005 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee report. http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/Publications/DietaryGuidelines/2010/DGAC/Report/AppendixE-3-3Vegetarian.pdf. Accessed August 26, 2013. 18 Craig WJ, Mangels AR. Position of the American Dietetic Association: Vegetarian Diets. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009 Jul;109(7):1266-82. 19 Craig W Health Effects of Vegan Diets. Am J Clin Nutr May 2009 vol. 89 no. 5 1627S-1633S. Guertin E. Following MyPyramid the plant-based way: effects on food patterns and nutrients. Nutr Today. 2012;47(1):7-22. 21 Soyfoods Association of North America. Tofu. http://www.soyfoods.org/soy-products/soy-fact-sheets/tofu. Accessed August 29, 2013. 22 US Department of Health and Human Services, US Department of Agriculture. 2005 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee report. http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2005/report. Accessed August 26, 2013. 20 1050 17th Street, N.W. • Suite 600 • Washington, DC 20036 • USA 4 To achieve more plant-based diets, soyfoods offer a wide variety of flavors, textures and forms. As noted earlier, soyfoods have evolved over thousands of years to accommodate traditional eating patterns as well as more American fares. Table 3 below displays the nutrient content of a large array of soyfoods compared to more common foods in the American diet. It should be evident that soyfoods contain comparable amounts of the nutrients of concern as their animalbased counterparts, but often at lower levels of energy, saturated fat, and cholesterol. 23 US Department of Health and Human Services, US Department of Agriculture. Report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 2010. http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/DGAs2010DGACReport.htm Accessed August 26, 2013. 1050 17th Street, N.W. • Suite 600 • Washington, DC 20036 • USA 5 Table 1 1050 17th Street, N.W. • Suite 600 • Washington, DC 20036 • USA 6 Table 2 1050 17th Street, N.W. • Suite 600 • Washington, DC 20036 • USA 7 Table 3: Soyfood Nutrient Comparison Chart Based on USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release #25 for Eggs Based on USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release #25 for tofu, raw, firm, prepared with calcium sulfate Based on USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release #25 for beef, ground, 80% lean meat / 20% fat, patty, cooked, pan-broiled Based on USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release #25 for soy burger 5 Based on USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release #25 for Tempeh, cooked 6 Based on USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release #25 for USDA Commodity, cheese, cheddar, reduced fat 7 Based on Nutrient Data for SoySation Cheddar Style cheese 8 Based on USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release #25 for Chicken, broilers or fryers, breast, meat only, cooked, original seasoning 9 Based on Nutrient Data for Lightlife Chickenless Chicken 10 Based on USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release #25 for Spaghetti cooked without added salt 11 Based on Nutrient Data for Explore Asian Soybean Spaghetti 12 Based on USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release #25 for Yogurt, plain, whole milk, 8 grams protein per 8 ounce 13 Based on Nutrient Data for WholeSoy Plain Cultured Soy 14 Based on USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release #25 for Potato chips, plain, salted 15 Based on USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release #25for Soy chips or crisps, salted 16 Based on USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release #25 for Ice creams, vanilla 17 Based on Nutrient Data for Turtle Mountain on Soy Delicious Old Fashioned Vanilla 18 Based on USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release #25 for Sausage, Italian, pork, cooked 19 Based on Nutrient Data for Tofurky Italian Sausage 20 Based on USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release #25 for Turkey Bologna 21 Based on Nutrient Data for Yves Soy Deli Slices Bologna *Fortified Nasoya tofu provides 1.8mcg B12, 9 IU vitamin E and 1500 IU vitamin A. **Vitamin E is not listed in the USDA nutrient database for this product, some commercially available brands have ~6 AE of Vitamin E 1050 17th Street, N.W. • Suite 600 • Washington, DC 20036 • USA 8 Soymilk Delivers Important Nutrients in the Dairy Group Fortified soymilk, which accounts for more than 95 percent of the soymilk consumed in the U.S., is a good source of calcium, Vitamin A, Vitamin D, riboflavin, potassium, magnesium, phosphorus, high-quality protein, and additional vitamins and minerals comparable to dairy, but without saturated fat or cholesterol. MyPlate recognized the comparability of fortified soymilk to cow’s milk and included calcium-fortified soymilk in the Dairy Group. By identifying the option for Americans to choose fortified soymilk in place of cow’s milk, the Dietary Guidelines better serves a diverse population who avoid dairy products for health, religious, or other special needs. Table 4 below provides the nutritional composition of 8 fluid ounces of regular, low fat, and unsweetened fortified soymilk compared to various cow’s milks and other plant-based beverages. To date, only fortified soymilks have met the USDA requirement of “nutritionally equivalent to milk” and are used in the WIC program,24 the National School Lunch and Breakfast Programs,25 and the Child and Adult Care Food Programs. Although questions about the bioavailability of calcium from soymilk and tofu may arise, several studies26,27,28 have noted that when appropriate analytical methods are used, the bioavailability of calcium in fortified soyfoods is comparable to calcium in cow’s milk. The calcium added to nondairy beverages may need to be re-suspended by shaking the container prior to consumption. Calcium status of an individual varies widely and depends not only on the availability and bioavailability of calcium in the diet, but also its retention in the bones; thus, many factors impact calcium status. For those who seek plant-based sources of calcium, calcium-fortified soymilk and tofu along with other legumes, and dark leafy greens have provided individuals a reliable source. Calcium-fortified soymilk is an excellent source of calcium for people who suffer from severe lactose intolerance, have milk allergies, or avoid milk for cultural, religious, or other personal reasons. Research Shows Role of Soyfoods in Reducing Risk of CHD, Metabolic Syndrome, Diabetes, and Cancers In 2013, more than 75 percent of consumers perceived soy products as healthy on an aided basis, which is an 8 percent increase over 15 years.29 On an unaided basis, consumers most frequently mention the following specific health benefits of soy: It’s good for you (18 percent, up from 14 24 Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC): Revisions in the WIC Food Packages; Interim Rule. Federal Register, Code of Federal Regulations, 7CFR, Part 246, Dec. 6, 2007;72:68966– 69032. 25 Fluid Milk Substitutions in the School Nutrition Programs. (7CFR Parts 210 and 220) Fed Regist. September 12, 2008;73:52903–52908. 26 Weaver CM, Heaney RP, Connor L, Martin BR, Smith DL, Nielsen S. Bioavailability of calcium from tofu as compared with milk in premenopausal women. Journal of Food Science, 2002:3144- 3147. 27 Heaney RP, Dowell MS, Rafferty K, Bierman J. Bioavailability of the calcium in fortified soy imitation milk, with some observations on method. Am J Clin Nutr, 2000:1166-9 28 Zhou Y, Martin B, and Weaver C. Calcium Bioavailability of Calcium Carbonate Fortified Soymilk Is Equivalent to Cow’s Milk in Young Women. J. Nutr. October 1, 2005 vol. 135 no. 10 2379-2382. 29 United Soybean Board. Consumer Attitudes about Nutrition. July 2013. Soy Connection. Accessed 8.13.2013, www.soyconnection.com/sites/default/files/Soy_Connection_Consumer_Attitudes.pdf 1050 17th Street, N.W. • Suite 600 • Washington, DC 20036 • USA 9 percent in 2012), source of protein (16 percent), low in fat (14 percent), heart healthy (12 percent), good for women (11 percent), and cholesterol lowering (10 percent). Consumers have increased focus on high-protein content of soyfoods associated with benefits of increasing satiety and curbing appetite. These perceptions are based on a significant body of evidence that associate intakes of soyfoods with favorable health outcomes. Research has found a positive influence of higher protein intake and greater eating frequency on appetite control and weight loss in overweight and obese individuals.30,31,32,33,34 Researchers35 at the U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine found that consuming twice the amount of protein as the Recommended Dietary Allowance along with an exercise plan and calorie restricted diet prevented muscle loss among young adults. Furthermore, soyfoods as part of a low fat diet with plenty of fruits and vegetables and a lifestyle of regular exercise may reduce risks of CHD, type 2 diabetes, and cancer or related clinical endpoints. The research of David Jenkins, MD, PhD, on the dietary portfolio of cholesterol-lowering foods, such as soyfoods shows significant reduction in serum lipids in hyperlipidemia.36,37 Other research with moderate soy protein intakes show reductions in hyperlipidemia and other risk factors of cardiovascular disease. 38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47 In addition 30 Leidy HJ, Mattes RD, Campbell WW. Effects of acute and chronic protein intake on metabolism, appetite, and ghrelin during weight loss. Obesity. 2007;15(5):1215-25. 31 Leidy HJ et al. The influence of higher protein intake and greater eating frequency on appetite control in overweight and obese men. Obesity. 2010;18(9):1725-32. 32 Westerterp-Plantenga MS,et al. Dietary protein, weight loss, and weight maintenance. Annu Rev Nutr. 2009;97(34):414-9. 33 Cope MB, Erdman JW, Jr., Allison DB. The potential role of soyfoods in weight and adiposity reduction: an evidence-based review. Obes Rev. 2008;9:219-35. 34 Maskarinec G, Aylward AG, Erber E et al. Soy intake is related to a lower body mass index in adult women. J Nutr. 2008;47(3):138-44. 36 Jenkins DJ et al. Effect of a dietary portfolio of cholesterol-lowering foods given at 2 levels of intensity of dietary advice on serum lipids in hyperlipidemia. JAMA. 2011;306(8):831-39. 37 Jenkins DJ et al. The effect of a plant-based low-carbohydrate (‘Eco-Atkins’) diet on body weight and blood lipid concentrations in hyperlipidemic subjects. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1046–54. 38 Harland J, Haffner T. Systematic review, meta-analysis and regression of randomized controlled trials reporting an association between an intake of circa 25g soya protein per day and blood cholesterol. Atherosclerosis. 2008;200:13-27. 39 Pipe EA, Gobert CP, Capes SE, Darlington GA, Lampe JW, Duncan Soy protein reduces serum LDL cholesterol and the LDL cholesterol:HDL cholesterol and apolipoprotein B:apolipoprotein A-I ratios in adults with type 2 diabetes. Am J Nutr. 2009;139:1700-06. 40 Jenkins DJ, Mirrahimi A, Srichaikul K, Berryman CE, Wang L, Carleton A, et al. Soy protein reduces serum cholesterol by both intrinsic and food displacement mechanisms. J Nutr 2010;140:2302S-2311S. 41 Maki KC, Butteiger DN, Rains TM, Lawless A, Reeves MS, Schasteen C, et al. Effects of soy protein on lipoprotein lipids and fecal bile acid excretion in men and women with moderate hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Lipidol. 2010;4:531-42. 42 Santo AS, Santo AM, Browne RW, Burton H, Leddy JJ, Horvath SM, Horvath PJ. Postprandial lipemia detects the effect of soy protein on cardiovascular disease risk compared with the fasting lipid profile. Lipids. 2010;45:1127-38. 43 Anderson JW and Bush HM. Soy protein effects on serum lipoproteins: A quality assessment and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled studies. Jour Amer Coll Nutr. 2011;30:79–91. 44 Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Kono N, Azen SP, Shoupe D, Hwang-Levine J, Petitti D, Whitfield-Maxwell L, Yan M, Franke A, Selzer RH. Isoflavone soy protein supplementation and atherosclerosis progression in healthy postmenopausal women. Stroke. 2011;42:3168-75. 1050 17th Street, N.W. • Suite 600 • Washington, DC 20036 • USA 10 to reducing hyperlipidemia, soyfoods have shown positive impact on diabetes and the metabolic syndrome.48,49,50 . More research is needed to establish the direct link between soy intake and these disease states which are associated with many factors. Table 4: Nutritional Content of Fortified Soymilk, Other Plant Beverages and Cow’s Milk Based on USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release #16 for Milk 3.5% fat Based on USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release #25 for Soymilk original and vanilla, Calcium and Vitamin A and D added 3 Based on USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release #25 for Milk 1% fat Vitamin A and D added 4 Based on USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release #25 for Soymilk, original and vanilla, light, Calcium and Vitamin A and D added 5 Based on USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release #25 for Soymilk (all flavors) unsweetened, Calcium and Vitamin A and D added 6 Based on Nutrient Data for Silk Almond milk original 7 Based on USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release #25 for Rice drink, unsweetened, Calcium and Vitamin A and D added 8 Based Nutrient Data for Silk Coconut milk 9 Based Nutrient Data for Pacific all natural Hemp original Soyfoods Have an Important Role in the Diets of Children In many cultures, tofu and other soyfoods are introduced as early weaning foods. Evidence, though inconclusive, from a small number of epidemiologic studies is emerging that specific aspects of the diet during preadolescence and adolescence impact risk of breast cancer. 51,52,53,54 45 Noroozi M, Zavoshy R, Jahanihashemi H. The effects of low calorie diet with soy protein on cardiovascular risk factors in hyperlipidemic patients. Pak J Biol Sci. 2011;14:282-87. 46 Wofford MR, Rebholz CM, Reynolds K, Chen J, Chen C-S, Myers L, Xu J, Jones DW, Whelton PK, He J. Effect of soy and milk protein supplementation on serum lipid levels: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2012;66(4):419-25. 47 Lerman RH, Minichj DM, Darland G et al. Subjects with elevated LDL cholesterol and metabolic syndrome benefit from supplementation with soy protein, phytosterols, hops rho iso-alpha acids, and Acacia nilotica proanthocyanidins. J Clin Lipidol. 2010;(1):59-68. 48 Guevara-Cruz M et al. A dietary pattern including nopal, chia seed, soy protein, and oat reduces serum triglycerides and glucose intolerance in patients with metabolic syndrome. J Nutr. 2012;142(1):64-9. 49 Cederroth, Christopher R. and Serge Nef. Soy, phytoestrogens and metabolism: A review. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;304:30–42. 50 Lerman RH, Minichj DM, Darland G et al. Subjects with elevated LDL cholesterol and metabolic syndrome benefit from supplementation with soy protein, phytosterols, hops rho iso-alpha acids, and Acacia nilotica proanthocyanidins. J Clin Lipidol. 2010;(1):59-68. 51 Mahabir S. Association between diet during preadolescence and adolescence and risk for breast cancer during adulthood. J Adolesc Health. 2013 May;52(5 Suppl):S30-5. 1050 17th Street, N.W. • Suite 600 • Washington, DC 20036 • USA 11 For example, during preadolescence and adolescence, severe calorie restriction with poor food quality and high total fat intake tend to increase risk, whereas high soy intake decreases risk. These studies55,56 and other early studies57,58 prompted the hypothesis that exposure to western diet and lifestyle at an early age was critical to breast cancer development. The 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee should recommend that federal nutrition programs and nutrition education should recognize cultural differences in dietary patterns and incorporate cultural menu items frequently to promote a return to healthier diets for some families. For schools that have incorporated soyfoods as regular options on menus, children have high acceptance.59 Allergies, a common concern for young children, often require use of soyfoods. Many schools and child care centers are offering soy nuts and soy nut butter in place of peanuts, and serving soymilk in place of cow’s milk to reduce potential exposure to severe allergens. Although soy has been listed as one of the eight major allergens, its frequency is substantially lower than the other seven. The College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (CAAI) estimates that approximately 0.4 percent of American children, or about 298,410 under the age of 18,60 are allergic to soy, whereas the more prevalent allergies report milk (32 percent), followed by peanuts (29 percent), eggs (18 percent), and tree nuts (6 percent).61 Researchers recently found that nearly 70 percent of patients enrolled in their study had outgrown their soy allergy by the age of 10, but an individual’s level of IgE may be the predictor of whether the allergy will persist.62 Furthermore, soy allergy symptoms are usually mild; and an anaphylaxis reaction to soy is extremely rare, according to CAAI. Another topic for soyfoods and children is the role of soyfoods in growth and development. Although the 2015 DGAC will not make dietary recommendations for children younger than 2 years of age, soymilk formula is comparable to milk-based formula and is the first exposure to soyfoods in the diets of about 20 percent of infants for growth and development when breastfeeding is not an option. 63 To confirm the healthfulness and safety of soyfoods in young children, SANA offers a brief summary of the preliminary findings of the Arkansas Children’s 52 Korde LA, Wu AH, Fears T, et al. Childhood soy intake and breast cancer risk in Asian American women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009; 18: 1050-9. 53 Wu AH, Yu MC, Tseng CC, et al. Dietary patterns and breast cancer risk in Asian American women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Apr;89(4):1145-54. 54 Lee SA, Shu XO, Li H, et al. Adolescent and adult soy food intake and breast cancer risk: results from the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Jun;89(6):1920-6. 55 Ziegler R; Hoover R, Pike M, et al. Migration patterns and breast cancer risk in Asian-American women. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993:85:1819-27 56 Buell P. Changing incidence of breast cancer in Japanese-American women. J Natl Cancer Inst 1973;51:1479-60. 57 Dunn JJ. Breast cancer among American Japanese in the San Francisco Bay area. Natl Cancer Inst monogr 1977;47:157-60. 58 MacMahon B, Cole P, Brown J. Etiology of human breast cancer: A review. J Natl Cancer Inst 1973;50:21-42. 59 Lazar K, Chapman n, and Levine E. Soy Goes to School: Acceptance of Healthy, Vegetarian Options in Maryland Middle School. J of School Health. April 2010, 80 (4): 209-215. 60 Soy Allergy. American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. Accessed on August 26, 2013, http://www.acaai.org/allergist/allergies/Types/food-allergies/types/Pages/soy-allergy.aspx. 61 Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Conover-Walker MK, Wood RA. Food-allergic reactions in schools and preschools. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001:155;790-5. 62 Savage JH, Kaeding AJ, Matsui EC, Wood RA. The natural history of soy allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010 Mar;125(3):683-6. 63 Bhatia J, Greer F. and Committee on Nutrition. Use of Soy Protein-Based Formulas in Infant Feeding. Pediatrics Vol. 121 No. 5 2008 pp. 1062 -1068. 1050 17th Street, N.W. • Suite 600 • Washington, DC 20036 • USA 12 Nutrition Center (ACNC) “Beginnings Study”, a prospective study to compare breast milk and dairy and soy formulas’ impact on growth and development. With respect to growth, development, and body composition, this ACNC study64 found soy-formula-fed infants’ patterns tracked closely with those of breast-fed infants. When soy formula did not track breast feeding, soy-formula-fed infants closely tracked patterns of milk-formula-fed infants. Using ultrasonically determined volumes of reproductive organs, this study did not find any estrogenic effects in the soy-formula-fed infants during the first four months of life when development of reproductive organs is rapid. Soyfoods Deliver High-Quality Protein with Efficient Use of Natural Resources The 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee has identified issues of sustainability as important when recommending dietary patterns. The primary drivers for the need for sustainable protein sources are the growing global population, evolving diets in developing economies, and shrinking land and water availability. Several research articles have demonstrated that edible soybeans used for soyfoods and soy protein ingredients contribute significantly to meeting dietary energy and quality protein requirements; these soybeans make efficient use of land, energy, and water resources. Soyfoods and soy protein are plant-based sources of complete protein.65 Soybeans and soy proteins are comparable to animal proteins as reported in Chart 1 from the Food and Agriculture Organization. 66 This FAO report suggests the Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) for isolated soy proteins is 1.067, indicating a complete protein on par with egg, whey, and milk proteins; whereas soybean and beef have a comparable PDCAAS score of slightly more than 0.90. (Refer to Chart 1.) Legumes and other vegetable sources of protein have PDCAAS values of less than 0.7, as they are limited by one or more essential amino acids or may be less digestible by the body. 64 Gilchrist, J.M., Moore, M.B., Andres, A., Estroff, J.A., Badger, T.M. 2010. Ultrasonographic patterns of reproductive organs in infants fed soy formula: Comparisons to infants fed breast milk and milk formula. Journal of Pediatrics. 156(2):215-220. 65 Beer WH, Murray E, Oh SH, Pedersen HE, Wolfe RR & Young VR. A long-term metabolic study to assess the nutritional value of and immunological tolerance to two soy-protein concentrates in adult humans. 1989 Am J Clin Nutr, 50:997-1007. 66 (FAO/WHO (1991). Protein Quality Evaluation; FAO Food and Nutrition Paper 51, Rome, Italy) 67 Hughes GJ, Ryan DJ, Mukherjea R, Schasteen CS. Protein digestibility-corrected amino acid scores (PDCAAS) for soy protein isolates and concentrate: criteria for evaluation. J Agric Food Chem. 2011 Dec 14;59(23):12707-12. 1050 17th Street, N.W. • Suite 600 • Washington, DC 20036 • USA 13 Chart 1 The meaning of sustainability used here is how well the production of a crop or livestock for human consumption uses land, water, and energy inputs. Because arable land for agriculture is a precious global resource, a focus on environmentally sustainable sources of complete protein nutrition emerge. Livestock is the primary user of arable land accounting for 78 percent of agricultural land and as much as 33 percent of cropland is used to produce animal feed.68 Some estimates suggest that in 2010 cattle will graze 24 million hectares of land that was forest in 2000.69 Based on an analysis by LMC International, soybeans make the most efficient use of land to produce a complete protein for human health. As seen in Chart 2, soy delivers 941 pounds of protein per acre of land, while the next most efficient land user is egg at only 212 pounds per acre. (Estimates of protein per acre were prepared by LMC International modeling using USDA data on crop yields and protein content of foods and expert advice on animal husbandry.)70 Jutzi, S. et al. (2006). Livestock’s long shadow. The FAO’s Livestock Environment and Development (LEAD) Initiative. The report is available here: http://www.fao.org/docrep/010/a0701e/a0701e00.HTM 69 Wassenaar, T., Gerber, P., Verburg, P. H., Rosales, M., Ibrahim, M. & Steinfeld, H. (2007). Projecting land use changes in the neotropics: the geography of pasture expansion into forest. Global Environmental Change, 17(1), 86104. 70 LMC International. Soy Soyfoods and Soy Protein in the Human Diet: A Tool in the Quest for Food Sustainability. Review and interpretation of the literature, January 2011. Paper available here: http://www.soyfoods.org/wp-content/uploads/LMC-SANA-Soyfoods-Sustainability-Lit-Review_final_complete.pdf 68 1050 17th Street, N.W. • Suite 600 • Washington, DC 20036 • USA 14 Chart 2 As freshwater resources become strained and food production becomes compromised, production of foods will be measured by volume of water needed to produce high-quality protein. Soybeans are the most efficient protein source per cubic meter of water used in production.71 The International Water Management Institute estimates that by 2023, water scarcity could cause the loss of up to 350 million metric tonnes of food. In chart 3, Liu found that soy is efficient in terms of unit of water per energy compared to animal products.72 Brummett also found rain-fed soybeans deliver about 106 grams of protein per cubic meter of water; rice delivers approximately 40 grams of protein per cubic meter of water, as seen in Chart 4. 71 Brummett, R. E. (2007). Comparative analysis of the environmental costs of fish farming and crop production in arid areas. In D.M. Bartley, C. Brugère, D. Soto, P. Gerber and B. Harvey (eds). Comparative assessment of the environmental costs of aquaculture and other food production sectors: methods for meaningful comparisons. FAO/WFT Expert Workshop. 24-28th April 2006, Vancouver, Canada. FAO Fisheries Proceedings. 10, 221–228. Essay available here: http://www.fao.org/docrep/010/a1445e/a1445e00.HTM 72 Liu, J. and Savenije, H. H. G. (2008). Food consumption patterns and their effect on water requirements in China. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 12, 887–898. Online paper available here: http://www.hydrol-earth-systsci.net/12/887/2008/hess-12-887-2008.pdf 1050 17th Street, N.W. • Suite 600 • Washington, DC 20036 • USA 15 Chart 3 Chart 4 1050 17th Street, N.W. • Suite 600 • Washington, DC 20036 • USA 16 Lastly, considering the amount of fossil energy inputs (such as fuel, fertilizer, pesticides, transportation) required to produce soybeans, soy-based foods deliver the largest number of calories and highest protein density for human consumption per amount of fossil fuel input.73 Eshel and Martin also found soybeans are the most efficient food commodity at more than 400 percent, in terms of energy efficiency, which measured calorie output against fossil energy input to produce the soybeans. They found the energy efficiency, in terms of protein per energy input, of soybeans is nearly three times that of corn and more than ten times milk, as seen in Chart 5. Chart 5 As the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee considers constructing and recommending dietary patterns that maintain cultural preferences; encourage consumption of nutrient rich foods that are low in saturated fat and cholesterol; support cardiovascular health; and use efficiently natural resources that soyfoods be considered in their entirety. Thank you for your time, attention, and dedication to this critical and relevant public health report. Sincerely, Nancy Chapman, RD, MPH Executive Director 73 Eshel, G and Martin, P. A. (2006). Diet, Energy and Global Warming, Earth Interactions, 10, 1-17. 1050 17th Street, N.W. • Suite 600 • Washington, DC 20036 • USA 17