2012 status report and challenges for the next decade

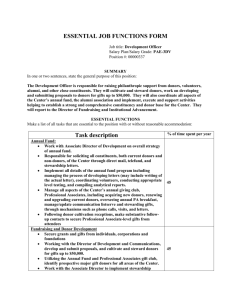

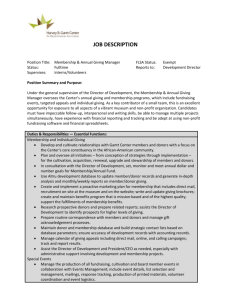

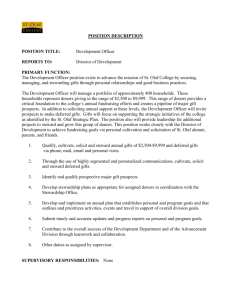

advertisement