Who decides in hard cases? - Health and Disability Commissioner

advertisement

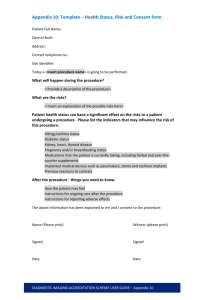

HDC Medico-Legal Conference 2012 “Creating a consumer-centred culture” Wednesday 17 October, Auckland; Thursday 18 October, Wellington Paper for Session Four WHO DECIDES IN HARD CASES? - THE BOUNDARIES OF COMPETENCE AND CONSENT Aaron Martin Director of Proceedings, Office of the Health and Disability Commissioner Wellington, NZ amartin@hdc.org.nz “It wanted about five minutes of eight when, taking the patient’s hand, I begged him to state, as distinctly as he could . . . whether he (M Valdemar) was entirely willing that I should make the experiment of mesmerizing him in his then condition. He replied feebly, yet quite audibly, “Yes, I wish to be. I fear you have mesmerized” – adding immediately afterwards, “deferred it too long.” From The Facts in the Case of M Valdemar, Edgar Allan Poe (1845) Overview Situations where a health or disability services consumer is not competent to make informed choices about, or consent to, treatment, may be highly emotionally charged and extremely demanding for the professionals involved. The first question a service provider must ask is what the consumer would choose if he or she were able to do so. What is expected of providers faced with this difficult question depends on what is reasonable in the circumstances, taking into account time and resource constraints. But framing the decision as an exercise of an emergency power to provide ‘best interests’ treatment risks losing sight of the consumer’s right to choose. Scenarios involving longer-term treatment are more likely to give rise to legal consent issues than emergency situations. There is, for example, uncertainty as to how long services may be provided to an incompetent consumer before an application is made for a court order. Treatment on an indefinite basis or continuing over an extended period without explicit consent may at some point become arbitrary, unreasonable, and unlawful. In practice however, it will not always be straight-forward to determine who should be responsible for applying for an order, or who should maintain oversight of the consumer’s interests after any order has been obtained. 2 Demographic trends towards an older population mean conditions such as dementia are likely to become more prevalent. It follows that legal provisions dealing with questions of adult competence and consent are also likely to assume increasing significance in our society.1 Right 7(4) in context - the Code as a framework for informed consent It has been suggested that the passage from Edgar Allan Poe’s short story quoted at the beginning of this paper contains one of the first descriptions of informed consent, long before the concept was recognised in medicine. 2 The narrator, a hypnotist, wishes to test whether mesmerism might arrest the process of death in a dying man. First, he has witnesses record his patient’s willingness to have the technique performed. Poe was clearly well ahead of his time. His depiction of the exchange between practitioner and patient suggests an appreciation not only of the importance of obtaining permission for what would follow, but also of diminishing competence as a complicating factor in doing so. (Those of you interested in the adverse event that awaited M Valdemar are referred to Poe’s account.) Although informed consent has long-since established itself in the medico-legal lexicon, the concept can still raise difficult practical questions of scope and content for providers of health and disability services. Right 7 of the Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers’ Rights3 provides for consumers to make informed choices and give informed consent. This paper discusses Right 7, with a particular focus on the place of Right 7(4) within that informed consent framework. Right 7(4) provides: (4) Where a consumer is not competent to make an informed choice and give informed consent, and no person entitled to consent on behalf of the consumer is available, the provider may provide services where (a) It is in the best interests of the consumer; and (b) Reasonable steps have been taken to ascertain the views of the consumer; and (c) Either, (i) If the consumer's views have been ascertained, and having regard to those views, the provider believes, on reasonable grounds, that Statistics New Zealand projections are that from the late 2020s the 65+ age group will make up over 20% of the 1 population (over 1 million people), compared with 13% in 2009. http://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/population/estimates_and_projections/demographic-trends2011/national%20demographic%20projections.aspx (accessed 10 October 2012). Altschuler, E. L., The Lancet, Volume 362, Issue 9394, Page 1504, 1 November 2003, doi:10.1016/S01406736(03)14710-1,http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(03)14710-1/fulltext (accessed 10 October 2012). 3Health and Disability (Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers’ Rights) Regulations 1996. 2 3 the provision of the services is consistent with the informed choice the consumer would make if he or she were competent; or (ii) If the consumer's views have not been ascertained, the provider takes into account the views of other suitable persons who are interested in the welfare of the consumer and available to advise the provider. Right 7(4) applies where a consumer is not competent and no proxy4 is available. In those circumstances, services may be provided where specified criteria are satisfied. Right 7(4) is however, best viewed as a right in itself, rather than as an exception to other provisions in Right 7 and elsewhere in the Code. In order to understand Right 7(4) in context, it is worth briefly considering Right 7(1), 7(2), 7(3), 7(5), and 7(7) and Clause 3 of the Code, the full text of which are set out in Appendix B to this paper. Services may only be provided where the consumer has made an informed choice and given informed consent, except where the law provides otherwise (Right 7(1)). Consumers are presumed competent unless there are reasonable grounds for believing otherwise (Right 7(2)). Where consumers have diminished competence, the right to informed choice and informed consent apply to the extent appropriate to their level of competence (Right 7(3)). If a consumer is not competent to consent, providers must ascertain whether anyone is entitled to consent on behalf of the consumer. If so, that person’s consent or refusal applies (subject to ss 18 and 98(4) of the Protection of Personal and Property Rights Act 19885). Only if no such person is available, is the provider justified in proceeding without consent, and then only where the other steps specified in Right 7(4) have been taken. Note however, that by virtue of Clause 3 of the Code, a provider will not be in breach of Right 7(4) if the provider has taken reasonable actions in the circumstances to give effect to the right and comply with the duties under that right (Clause 3(1)). The “circumstances” include the consumer’s clinical circumstances and the provider’s resource constraints (Clause 3(3)). Right 7(5) provides that every consumer may use an advance directive in accordance with the common law. Identifying any relevant advance directive is clearly one of the ways the views of a consumer may be ascertained for the purposes of Right 7(4). A person entitled to consent on a consumer’s behalf includes a welfare guardian or person exercising enduring power of attorney. 5 The powers of a welfare guardian and attorney do not extend, for example, to refusing consent to standard 4 medical treatments or procedures intended to save life or prevent serious damage to health (s 18(1)(c)). 4 Central to the ideas of consumer autonomy and informed consent is the principle that every consumer has the right to refuse services and to withdraw consent to services (Right 7(7)). Returning to the steps that apply under Right 7(4), it is axiomatic that the services provided must be in the best interests of the consumer (Right 7(4)(a)). Although this will mainly involve a clinical assessment by the provider of the consumer’s treatment needs, it may also involve taking a broader view of the consumer’s needs, interests, and quality of life, as required by Right 4(4) of the Code.6 The steps required of providers in Right 7(4)(b) and (c) boil down to taking reasonable steps to ascertain what the consumer would have wished to happen if he or she were competent. An important step is therefore to try to ascertain the consumer’s views about the proposed provision of services. If however, ascertaining these views is not possible, the views of other ‘suitable persons who are interested in the welfare of the consumer and available to advise the provider’ must be taken into account. Such people may include family, partners, friends or caregivers. The key point is that they have a relationship with the consumer that suggests they are interested in what will be in the consumer’s best interests.7 Having said this, it is important to emphasise that it is not a matter of obtaining the informed consent of a suitable person, as the procedure set out in Right 7(4) is premised on no one who is legally entitled to consent being available. Rather, at this stage the provider is only required to take into account the views of ‘suitable persons’. The provider would be wise to canvas the views of as many such people as may be reasonably available, and is not bound to take steps the provider regards as unreasonable on the strength of such advice.8 Note that, irrespective of the views of concerned persons, clinicians are never required to provide treatment that is not clinically appropriate or which conflicts with ethical standards. At the end of this paper there is a flow diagram of the Right 7(4) process. The flow diagram has been framed in a way that ensures the consumer’s wishes, to the extent that it may be possible to ascertain these, remain central to, and where possible inform, any treatment decision. It is worth noting that although in the text Right 7(4)(a) comes before Right 7(4)(b) and (c), in the flow diagram it is suggested the more logical sequencing has ‘best interests’ treatment as the final box. In terms of the decision-making process, if the steps in Right 7(4)(b) and (c) are required, the (4) Every consumer has the right to have services provided in a manner that minimises the potential harm to, and optimises the quality of life of, that consumer. 7Greig, K, “Informed Consent in the Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers' Rights”, 8 February 2000, 6 http://www.hdc.org.nz/education/presentations/informed-consent-in-the-code-of-health-and-disability-servicesconsumers'-rights (accessed 10 October 2012). Greig, K, “Informed Consent in the Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers' Rights”, above n 8. 8 5 consumer’s best interests cannot be determined until those steps have been completed. Emergency situations Jurisprudence suggests clinical decisions to provide ‘best interests’ treatment in emergency situations will very rarely result in a subsequent complaint or legal challenge.9 Most people will understandably be very grateful for the skill and judgment exercised by professionals who may have saved their life. Indeed, this is one reason why viewing Right 7(4) as a ‘necessity’ exception that applies in relation to ‘emergency services’ may risk losing sight of the bigger picture. Although emergency treatment may involve tense and traumatic situations, the application of Right 7(4) is likely to be relatively straight-forward in such circumstances, especially given what Clause 3 of the Code has to say about reasonable actions. In practice, the quality and content of consent to treatment is more likely to be called into question in situations involving longer term incompetence and intellectual disability. The ‘emergency’ setting is therefore dealt with here briefly, before moving on to consider longer term scenarios. Cole’s Medical practice in New Zealand10 offers this advice to doctors finding themselves in emergency situations where a patient is not competent to consent: If, in an emergency, immediate action must be taken to preserve the life or health of a patient, then you can provide the key services without consent. Only those treatments that are necessary to preserve life or health should be done at this time. Any procedure that can reasonably be delayed should be delayed until an opportunity can be given for the patient to consent. Occasionally, when a patient is unable or refuses to consent to treatment, a legal opinion should be sought with a view to seeking authority from the High Court. The Medical Council’s March 2011 guidance on ‘Information, choice of treatment and informed consent’ discusses Right 7(4) and adds (at [23]): If you have not been able to ascertain the patient’s views and no suitable person is available to give advice and the delay will not be harmful, it is wise to seek a second opinion from an experienced colleague before providing care. You should document this colleague’s views in the patient record. As Professor Peter Skegg puts it in Medical Law in New Zealand11: [E]ven if there is some uncertainty about what a patient would have chosen, treatment without consent will often be warranted. Patients should never be left to 9 P D G Skegg, R Paterson et al, Medical Law In New Zealand, Brookers Ltd, 2006 pp 243-244 and 247-248. St George, I, (ed), Medical Council of New Zealand, 2011, p89. P D G Skegg, R Paterson et al, above n 10, at 245. 10 11 6 die or suffer because of the mere possibility that they would have refused consent, had they had the opportunity to do so. By contrast with emergency scenarios however, are situations where a consumer is only temporarily unable to consent and it is reasonably possible to delay in order to allow his or her consent to be obtained. Consent to non-urgent elective surgery In December 2009 the Health Practitioners Disciplinary Tribunal issued an important decision on informed consent, particularly in terms of the obligations and duties of a surgeon when undertaking non-urgent elective surgery.12 A surgeon had proceeded with elective surgery despite knowing that the risks of death and of post-operative complications were significantly greater than those he had disclosed to his patient. The day before the surgery was to proceed, liver function tests (LFTs) were taken. However, the surgeon did not review these until after the patient was anaesthetised. The LFTs showed significant liver cirrhosis and therefore increased the risk of death from the one percent that the patient had been informed about to somewhere in the vicinity of 15 to 22 percent. Rather than wake his patient to discuss this and the various options that were available to the patient, the surgeon continued with surgery. Sadly, the patient developed post-operative complications and died some three weeks later. The Tribunal confirmed that the significantly greater risk of death was material information and that the patient should have had the opportunity to reconsider whether he still wished to proceed with the operation. The Tribunal rejected the surgeon’s argument that by proceeding with the operation he was acting in his patient's best interests, noting that it was not the surgeon’s decision whether or not to proceed but that of his patient. It also rejected the surgeon’s argument that he faced a clinical dilemma, stating that any so-called dilemma was entirely of his own making as it was a result of a succession of failures by him to make adequate enquiries before he arrived at the hospital to perform the operation. The Tribunal considered it was pure conjecture to say what the patient might have chosen had he been given the choice prior to the operation. Further, the Tribunal rejected the submission that the surgeon knew the patient sufficiently well to make a decision to proceed with the surgery without first informing him of the increased risks and other options open to him. The Tribunal also rejected the submission that the situation could be remedied by a post-surgery conversation during which the surgeon said the patient had retrospectively given approval for what had occurred. Med09/113D. 12 7 Thinking about Right 7(4) Take a moment now to consider the following two working summaries of Right 7(4). First, consider each statement on its own, from a pragmatic standpoint without overanalysing. Next, compare the two statements and choose the one you think best reflects the requirements of Right 7(4): (1) Right 7(4) is an ‘emergency’ exception to informed consent principles, permitting ‘best interests’ treatment where a consumer is not competent to consent, no proxy is available and, time permitting, any ‘significant others’ or family have been consulted. (2) Right 7(4) means that, even when a consumer is not competent to consent, informed consent principles require providers to take reasonable steps to find out what the consumer would wish to happen, and act accordingly. Considered individually, did you find that either statement could pass muster as a working summary of Right 7(4)? Did you find choosing between the two statements straight-forward? Or did you find the juxtaposing of the two statements set up a degree of conflict between them? No doubt both statements could be improved upon. However, as by now you may anticipate, it is here argued that the second statement is the one that best accords with the intent of Right 7(4), and better reflects its proper context within Right 7. The object of the above exercise was to suggest that the way a problem is framed – in this case the application of Right 7(4) to a particular case – may in itself have implications for the way we approach the problem. But does it really make any practical difference how we think about Right 7(4)? Arguably it could do. If, for example, we think about Right 7(4) as an exception to other rights dealing with informed consent or as an 'emergency' power akin to the common law doctrine of ‘necessity’, we may unconsciously over-emphasise a notion of presumed (as opposed to explicit) consent. If, on the other hand, we approach Right 7(4) as a consumer-centred provision, we may be more intentional about identifying any evidence of what the consumer would actually choose, were he or she competent to do so. In thinking about Right 7(4) it is important not to substitute a presumed mandate to act (albeit in the consumer's best interests) for the clear requirement in Right 7(4) to first enquire into the consumer's actual wishes. This does not ignore the possibility that it may be unreasonable to expect clinicians to ascertain a consumer’s wishes in the time available and given resource constraints. As already mentioned, those limits on Right 7(4) are provided for through the application of Clause 3 of the Code. In practice however, the difficult legal issues in applying Right 7(4) are more likely to arise in relation to a long-term resident in a dementia unit than an unconscious patient brought into A & E. In situations where providers can reasonably be expected to have the time and 8 resources at their disposal to make enquiries about a consumer’s wishes before he or she became incompetent, simply framing Right 7(4) as a ‘presumed consent’ emergency power may diminish the quality of decisions made under it. Speaking about the ‘framing effect’ generally, psychologist and Nobel Prize winner in economics Daniel Kahneman suggests we would do well to ask ourselves: “Do we still remember the question we are trying to answer? Or have we substituted an easier one?”13 Kahneman cites an experiment undertaken by his colleague Amos Tversky and others at Harvard Medical School. Doctors were asked to choose between two lung cancer treatments: surgery and radiation. For half the doctors the short-term outcome of surgery was framed in terms of a survival rate: The one-month survival rate is 90%. Framed this way, 84% of doctors chose surgery. For the other half of the doctors in the study, the problem was framed in terms of a mortality rate: There is 10% mortality in the first month. Although this second description is logically equivalent to the first description, only 50% of doctors favoured surgery over radiation when the question was framed in this way. According to Kahneman, the explanation is this: [M]ortality is bad, survival is good, and 90% survival sounds encouraging whereas 10% mortality is frightening.14 The general proposition emerging from research of this kind is that how a critical question is framed can produce dramatically different answers - even when the information available is the same. Let’s take another example, this one discussed in the book Nudge by Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein.15 In many countries including our own, a driver’s licence records a person’s willingness (or otherwise) to donate organs in the event of Kahneman, D, Thinking fast and slow, Penguin Books, 2011, p 104. Kahneman, above n 14, at 367. 15Yale University Press, 2008. 13 14 9 death in a car accident. How this information is collected differs from country to country, with some countries inviting drivers to opt-in to organ donation (i.e. requiring explicit consent) and other countries applying a default rule that drivers agree to donate unless they opt-out (i.e. presumed consent). A study in 2003 found that in Germany, where the driver must opt-in, only 12 per cent of drivers consented to being donors. In Austria on the other hand, where a default presumed consent rule applies, 99 per cent of drivers were recorded as donors.16 (Equivalent figures have been noted for Denmark (4%) and Sweden (86%), again neighbouring and culturally similar countries where the only difference appears to be the default rule.17) On the face of it, presumed consent is the opposite of explicit consent and the marked differences caused by the format of the critical question are surprising. This, it has been suggested, is the framing effect in action. Thaler and Sunstein go on to make an observation that may be particularly germane to our discussion of Right 7(4): Determining the exact effect of changing the default rule is difficult because countries vary widely in how they implement the law. France is technically a presumed consent country, but physicians routinely ask the family members of a donor for their permission, and they usually follow the family’s wishes. This policy blurs the distinction between presumed consent and explicit consent.18 [Emphasis added] So, it appears that even when the underlying choice is the same, the way in which we ask ourselves a question can affect the answer we come up with. Arguably, the outcome of decision-making under Right 7(4) may differ depending on whether the starting point is ‘presumed consent’, or identifying any evidence of explicit consent (i.e. what the consumer would choose). As Thaler and Sunstein suggest in relation to organ donation, routinely talking to family members may in itself blur the distinction between presumed consent and explicit consent. Having said this however, it is important to reiterate that Right 7(4) does not require clinicians to seek permission from the family, nor does it sanction following the family’s wishes where those are not in the best interests of the patient. For a limited time . . .? Right 7(4) is not time-bound and can therefore arguably apply over extended periods of time. That it is silent on the period of time for which it may be applied is another reason it is best not viewed as an 'emergency' power or as an ‘exception’ Thaler and Sunstein, above n 16 at 179. Kahneman, above n 14, at 373. 18Kahneman, above n 14, at179. 16 17 10 akin to the common law doctrine of necessity. Although there will often be emergency situations in which it can be applied, there will also be other situations where it is arguably much more relevant. A related point is that if Right 7(4) can be relied on for the provision of extended and ongoing treatment, then there will also be ongoing obligations on providers. A 43-year old woman with a complex history that included severe psychological trauma, depression and alcohol abuse, was admitted to hospital in May 2007 in a confused state. She was assessed as not having capacity to make decisions about her own care, and it was decided that an application should be made for a court order to place her in an appropriate residential facility. The application was prepared but never filed with the court. In August 2007 the woman was discharged from hospital and placed by a needs assessment and service co-ordination service (NASC) in a secure dementia unit caring mostly for older people. She understood she was legally required to live there. She was assessed by the NASC three times over the following ten months, and on each occasion she expressed her wish to leave the dementia unit and to live somewhere more suitable. At various times she clearly expressed her frustration at having to live in the dementia unit, and was recorded as being unhappy and increasingly depressed about her situation. In August 2008 the Community Alcohol and Drug Service discovered there was no court order and therefore no legal requirement for the woman to remain in the dementia unit if she did not wish to be there. Over the following two months, arrangements were made for the woman's transition and she left the unit in October 2008.19 This case illustrates not so much ‘presumed consent’ but an erroneous assumption that there was a court order in place. If however, Right 7(4) had been engaged in that case, how long would it have been appropriate to treat the consumer in reliance on that provision in the Code? Would there come a point when it would be expected that clinicians would seek a court order for continuing treatment? Such an order might at least provide the protections of periodic review so that the consumer could challenge the order in the event he or she regained a sufficient degree of competence. If the consumer were being treated against a background where there had been clearly documented discussions with family members, would that affect the decisions about how long Right 7(4) could be relied on, or whether a court order should be applied for? Needs Assessment and Service Co-ordination Service – HRRT No. 024/2011 [2012] NZHRRT 3 (22 March 2012); Rest Home – HRRT No. 025/2011 [2012] NZHRRT 4 (22 March 2012); The Human Rights Review Tribunal's decisions in these cases are available at http://www.nzlii.org/nz/cases/NZHRRT/2012/. 19 11 One possible route through this uncertainty as to how long a consumer may be treated under Right 7(4) may lie in the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990. Section 22 of that Act provides that everyone has the right not to be arbitrarily arrested or detained. Section 11 provides that everyone has the right to refuse to undergo any medical treatment. Wherever an enactment can be given a meaning that is consistent with the rights and freedoms contained in the Bill of Rights, that meaning shall be preferred to any other meaning (s 6). However, recourse to these provisions only takes us so far. Just as clause 3 of the Code provides for reasonable action in the circumstances, the rights and freedoms contained in the Bill of Rights may be subject to such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society (s 5). A high profile UK case concerned a mental health service consumer who lacked the capacity to consent to treatment or detention as an ‘informal’ inpatient in Bournewood Hospital. Relevant legislation at the time (1997) provided for informal admission of patients, namely, those with legal capacity to consent who do consent to admission for treatment, or those persons without legal capacity to consent to treatment but who are admitted for treatment on an “informal basis” as they do not object to that admission. In this particular case, the hospital did not consider that formal committal was necessary because the patient was compliant and did not resist admission. The question that was subject to extensive judicial review proceedings was whether for the purposes of informal admission under the relevant legislation the patients needed to have legal capacity to consent and to explicitly consent to admission, or whether compliant and non dissenting patients could also be admitted informally. If the statute did not provide for admission of a compliant and non dissenting patient then the questions were whether the patient in this case had in fact been detained and, if so, whether that detention was justified under the common law doctrine of necessity. In the House of Lords, Lord Steyn recognised the importance of procedural safeguards for compliant incapacitated patients: The common law concept of necessity is a useful concept, but it contains none of the safeguards of the Act of 1983. It places effective and unqualified control in the hands of the hospital psychiatrist and other health care professionals. It is true, of course, that such professionals owe a duty of care to patients and that they will almost invariably act in what they consider to be the best interests of the patient. But neither habeas corpus not (sic) judicial review are sufficient safeguards against misjudgements and professional lapses in the case of compliant incapacitated patients. Given that such patients are diagnostically indistinguishable from compulsory patients, there is no reason to withhold the specific and effective protections of the Act of 1983 from a large class of vulnerable mentally incapacitated 12 individuals. Their moral right to be treated with dignity requires nothing less.20 The case was appealed all the way to the European Court of Human Rights where it was ultimately decided in the context of Articles 1 and 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights. The Court considered the key fact in relation to whether the patient was ‘detained’ to be that the health care professionals treating and managing the patient exercised complete and effective control over his care and movements. The Court decided that it was not determinative whether the ward was locked or lockable. The Court21 concluded therefore that the patient was deprived of his liberty. The Court found that there was an absence of procedural safeguards to protect against arbitrary deprivations of liberty when detaining a patient informally on the grounds of necessity. As such, the detention of the patient was found to be arbitrary and therefore unlawful in contravention of Articles 1 and 5 of the Convention. Following the ruling of the European Court of Human Rights the UK government introduced new procedural safeguards known as the deprivation of liberty safeguards. The new procedures were introduced by the Mental Health Act 2007 as an amendment to the Mental Capacity Act 2005. These safeguards were intended to cover the so-called ‘Bournewood gap’ between informally admitted compliant and non dissenting patients and formally admitted patients. The safeguards came into force in April 2009. The safeguards, as they apply to hospital and care home residents, require six assessments to be made before detaining a person who lacks capacity to consent to that detention.22 The assessments relate to age, mental health, mental capacity, best interests, eligibility, and whether there has been a refusal of treatment in accordance with the provisions in the Mental Capacity Act. That Act encompasses five main principles:23 1 A presumption of capacity − Every adult has the right to make their own decisions and must be assumed to have capacity to do so unless it is proved otherwise. That capacity is presumed to be ongoing until there is evidence to the contrary. 2 The right for individuals to be supported to make their own decisions − All reasonable help and support should be provided to make their own decisions L, In re [1998] UKHL 24; [1999] AC 458; [1998] 3 All ER 289; [1998] 3 WLR 107; [1998] 2 FLR 550; [1998] 2 FCR 501; [1998] Fam Law 592 (25th June, 1998). 21Ref [91].H.L. v The United Kingdom (45508/99) Section IV, ECHR, 5 October 2004. 22 The safeguards applying to hospital and care home residents can be found in Schedule A1 to the Mental 20 Capacity Act 2005 (UK). 23Summarised by Nursing and Midwifery Council UK, www.nmc-uk.org, accessed 12 October 2012. 13 and to communicate those decisions where necessary, before it can be assumed that they have lost capacity. 3 It should not be assumed that someone lacks capacity simply because their decisions might seem unwise or eccentric. 4 If someone lacks capacity, anything done on their behalf must be done in their best interests. The Act provides a checklist of factors that all decision makers must work though in deciding what is in the best interests of the incapacitated person. 5 If someone lacks capacity, before making a decision on their behalf, all alternatives must be considered and the option chosen should be the least restrictive of their basic rights and freedoms. Interestingly, but perhaps not surprisingly, the principles accord with the main thrust of Right 7(4) of the Code. Concluding remarks – and some questions for discussion Right 7 is clearly intended to safeguard consumer autonomy and choice in relation to treatment and other services. It applies when consumers are arguably at their most vulnerable. In that context, Right 7(4) is best seen as a set of specific protections for consumers who are not competent to consent. It demarcates boundaries around consent based on competence, rather than simply providing an exception to informed consent principles. Against this background it would be surprising if Right 7(4) provided a legal basis for the provision of treatment and other services on an indefinite basis or for an extended period without explicit consent. Given a meaning consistent with the rights and freedoms contained in the Bill of Rights, prolonged and continuing reliance on Right 7(4) in a particular case may at some point become arbitrary, unreasonable, and unlawful. Just as Right 7(4) is silent on time limits, so too is it therefore silent on two important practical issues, raised here for further discussion: If there is no proxy, and no suitable person taking an interest in the consumer’s welfare, who should be responsible for applying for any court order? It may be that making an application is the responsibility of the provider, and the court may appoint counsel for the subject person. But who will maintain ongoing oversight after the court process is concluded and any orders made? With an aging population and inevitable fiscal constraints these questions warrant further consideration. 14 APPENDIX A – STATUTORY ROLE OF DIRECTOR OF HEALTH AND DISABILITY PROCEEDINGS The Director of Proceedings is an independent statutory officer appointed under the Health and Disability Commissioner Act 1994. Where the Health and Disability Commissioner (HDC) has found a serious breach of a consumer’s rights, HDC may refer the provider to the Director of Proceedings. The Director then reviews the Commissioner’s investigation file and makes an independent decision regarding whether to proceed or not. The Director can lay a disciplinary charge before the HPDT, issue proceedings before the HRRT, or both. The Director can also issue proceedings or provide representation in other forums (other tribunals, courts, or inquiries). The Director works with a small team of lawyers and an assistant reviewing files and prosecuting cases. Charges against registered health practitioners24 are heard before the HPDT. If the provider is not a registered health practitioner,25 the Director may file proceedings with the HRRT. The Tribunal may hear claims against bodies such as rest homes and district health boards, or against a registered health professional, regardless of whether disciplinary proceedings are also brought. Unlike the HPDT, the HRRT has the power to order the provider to pay compensation to a consumer. However, the Accident Compensation legislation limits the circumstances in which compensatory damages are available. The purpose of laying a charge in the HPDT is to ensure that standards for the profession are maintained, that the individual practitioner is held accountable for his or her actions, and that the public is protected. Proceedings in the HRRT are used to obtain remedies for the consumer and to set standards for providers, particularly non-registered providers. Therefore the work of the Director of Proceedings is important in helping to set professional standards for both registered and nonregistered providers. It also helps maintain public confidence in the quality and safety of services. Registered health practitioners include medical practitioners, nurses, midwives, dentists, psychologists, chiropractors, and pharmacists. 25Non-registered practitioners include providers such as counsellors, massage therapists, caregivers, rehabilitation workers and acupuncturists. 24 15 APPENDIX B – FULL TEXT OF RIGHT 7AND CLAUSE 3 OF THE CODE OF HEALTH AND DISABILITY SERVICES CONSUMERS’ RIGHTS RIGHT 7 Right to Make an Informed Choice and Give Informed Consent (1) Services may be provided to a consumer only if that consumer makes an informed choice and gives informed consent, except where any enactment, or the common law, or any other provision of this Code provides otherwise. (2) Every consumer must be presumed competent to make an informed choice and give informed consent, unless there are reasonable grounds for believing that the consumer is not competent. (3) Where a consumer has diminished competence, that consumer retains the right to make informed choices and give informed consent, to the extent appropriate to his or her level of competence. (4) Where a consumer is not competent to make an informed choice and give informed consent, and no person entitled to consent on behalf of the consumer is available, the provider may provide services where (a) It is in the best interests of the consumer; and (b) Reasonable steps have been taken to ascertain the views of the consumer; and (c) Either, (i) If the consumer's views have been ascertained, and having regard to those views, the provider believes, on reasonable grounds, that the provision of the services is consistent with the informed choice the consumer would make if he or she were competent; or (ii) If the consumer's views have not been ascertained, the provider takes into account the views of other suitable persons who are interested in the welfare of the consumer and available to advise the provider. (5) Every consumer may use an advance directive in accordance with the common law. (6) Where informed consent to a health care procedure is required, it must be in writing if (a) The consumer is to participate in any research; or (b) The procedure is experimental; or (c) The consumer will be under general anaesthetic; or (d) There is a significant risk of adverse effects on the consumer. 16 (7) Every consumer has the right to refuse services and to withdraw consent to services. (8) Every consumer has the right to express a preference as to who will provide services and have that preference met where practicable. (9) Every consumer has the right to make a decision about the return or disposal of any body parts or bodily substances removed or obtained in the course of a health care procedure. (10) No body part or bodily substance removed or obtained in the course of a health care procedure may be stored, preserved, or used otherwise than (a) with the informed consent of the consumer; or (b) For the purposes of research that has received the approval of an ethics committee; or (c) For the purposes of 1 or more of the following activities, being activities that are each undertaken to assure or improve the quality of services: (i) a professionally recognised quality assurance programme: (ii) an external audit of services: (iii) an external evaluation of services. 3 Provider compliance (1) A provider is not in breach of this Code if the provider has taken reasonable actions in the circumstances to give effect to the rights, and comply with the duties, in this Code. (2) The onus is on the provider to prove that it took reasonable actions. (3) For the purposes of this clause, the circumstances means all the relevant circumstances, including the consumer’s circumstances and the provider’s resource constraints. clinical 17 FLOW DIAGRAM OF RIGHT 7(4) PROCESS (Summary for discussion purposes only. Not intended as a substitute for legal advice.) Is consumer competent for informed choice/consent? Y INFORMED CONSENT REQUIRED N Is any person entitled to consent on behalf of consumer available? Y N Take reasonable steps to ascertain consumer’s views Have consumer’s views been ascertained? Take into account views of available suitable persons N Y Having regard to consumer’s views, are there reasonable grounds to believe services consistent with informed choice consumer would make? Y Provide services if in best interests of consumer N STOP