View/Open

advertisement

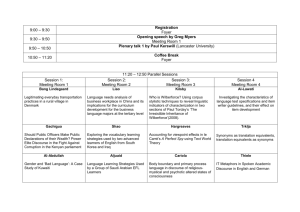

The business of pragmatics. The case of discourse markers in the speech of students of business English1 Lieven Buysse Hogeschool-Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium lieven.buysse@hubrussel.be 1. Introduction In foreign language learning grammar and vocabulary typically take centre stage, leaving only a marginal position, if any at all, for pragmatic features (cf. inter alia Pawlak 2010). Learners thus appear to be expected to learn a language with little attention to context and the array of social actions they can perform with the target language. Among these pragmatic devices are discourse markers2, i.e. small words that do not carry propositional weight but modify the message in various subtle ways, e.g. in order to contribute to coherence or build rapport with the interlocutor. These have been studied extensively in native speaker discourse over the past few decades for a multitude of languages (e.g. Schiffrin 1987; Bazzanella 1990; Hansen 1998; Maschler 1998; Wouk 1999; Beeching 2001; Aijmer 2002; Fischer 2006; Pons Bordería 2006; Amfo 2007) but their use in non-native spoken discourse has only recently started to attract some attention (e.g. Romero Trillo 2002; Jordà 2005; Müller 2005; Fung and Carter 2007; Hellermann and Vergun 2007; Gilquin 2008; Mukherjee 2009). This contribution gauges the extent to which these pragmatic items are used (and may hence be assumed to have been acquired) by two types of foreign language learners who have almost reached the end of formal instruction in English. The English speech of undergraduates of Commercial sciences will be compared with that of undergraduates of English Linguistics and that of native speakers of English. First I shall briefly sketch findings from previous research in section 2. Section 3 outlines the corpus data used for the present study, whereas section 4 provides the basic quantitative results. These are further discussed at length and tentatively explained in section 5. Finally, section 6 draws conclusions from these findings. 1 This paper is not intended for publication in its current form. The taxonomic debate in this research field is on-going, resulting in a plethora of terms that are used for much the same concept or for its sub-classes. Among these are: discourse markers, pragmatic markers, discourse particles, pragmatic particles, discourse operators, cue words, connective particles, … A fairly comprehensive list of the terms used in the field is provided by Fraser (1999: 932). 2 [1] 2. Previous research Foreign language learners have been reported to display a narrower range of pragmalinguistic forms with a more restricted and less complex inventory of pragmatic items than native speakers of the target language (Kasper and Blum-Kulka 1993). Romero Trillo (2002, 2007) distinguishes two types of discourse markers. On the one hand, operative discourse markers “deal with the management of concepts and language comprehension to make the conversation flow without disruption” (Romero Trillo 2007: 84). On the other hand, involvement discourse markers are those items that “deal with the management of social rapport to safeguard the face of the interactants” (Romero Trillo 2007: 84).3 Examples of the former are so, now and look, and examples of the latter are you know, like and kind of. Previous research on the use of discourse markers in non-native speech indicates that non-native speakers of English are able to use these items, albeit with differing frequencies, a restricted functional scope and varying results for individual markers. Fuller (2003) compares the discourse marker use of non-native speakers of English, all of whom had been staying in an English-speaking community for at least two years and have either German, French or Spanish as their mother tongue (L1), with that of native speakers. She finds that the non-native speakers used all of the discourse markers analysed (well, y’know, like, oh and I mean) and did so correctly. However, the frequency of discourse markers among non-native speakers is lower overall and they show less variation in the use of these discourse markers across the three speech contexts that she investigated than the native speakers. The non-native group of subjects also turn out to be less homogeneous in their use of discourse markers. Only for oh and well does Fuller conclude that “non-native speakers do effectively mimic the native speakers” (Fuller 2003: 206). On a more basic level, Hellermann and Vergun (2007) examine like, you know and well in dyadic classroom interaction among beginning adult learners of English from varying L1 backgrounds. The participants in the study barely made use of these markers, but frequently turned to so, alright, now and okay, i.e. markers considered “characteristic of transitions between activities and in the lesson” (2007: 175). These operative markers, the authors point out, are typical of teacher talk, which benefits the learners’ level of exposure to them and allows learners to more effectively take them over in their own speech. Müller (2005) scrutinises a corpus of dyad conversations in which participants retell and discuss a silent film they watched. She compares how the discourse markers so, well, you know and like are used in the English speech of native speakers of German and in that of Britons and Americans. The former turn out to employ all four markers but not all to the same extent: frequencies tend to differ as does the usage of individual functions with some being used by English native speakers and not by German native speakers and vice versa. The Germans greatly underuse so, as Müller records only half the number of tokens as for the native speakers. Results for you know and like are even more revealing with Germans using them only a fraction of the time of native speakers of English. Well, on the other hand, is used twice as often by the German subjects as by the native speakers. What is most striking is not so much 3 Aijmer (2002) makes a similar distinction between markers that function on a “structural or textual level” (2002: 40) and those that function on an “interpersonal or phatic level” (2002: 48). [2] the massive underuse of you know and like as the contrasting pattern for well and so – two operative discourse markers – among native speakers of German. Müller (2004, 2005) offers a few tentative explanations. Most importantly, it seems that well can substitute for so in an avoidance strategy. Because these markers show a partial functional correspondence and can both be translated into German also, speakers may use them interchangeably, at least for some functions. However, that does not explain the preference for well over so. An analysis of German EFL textbooks reveals that well is unrealistically overrepresented in course materials, as opposed to so (you know and like are even only scarcely present). Attitude also seems to play a role: some of the German participants in the study were asked later about their feelings regarding well and so, to which they replied that the former sounds more English or that they believe native speakers use it more frequently. In the present study the two types of discourse markers that Romero Trillo (2002, 2007) distinguishes will be in focus. Operative discourse markers are represented by so and well, and involvement discourse markers by you know, like, kind of/kinda/sort of4 and I mean. Following Schourup (1999) such linguistic items are considered to fulfil a discourse marker function if they meet three criteria: connectivity, nontruth-conditionality (i.e. they do not contribute to the propositional content of the utterance) and (semantic as well as syntactic) optionality (i.e. they can be left out without rendering the utterance unintelligible or ungrammatical). For instance, you know in an utterance such as you know the answer is not connective, carries propositional meaning and cannot be left out; therefore, such instances have been discarded from the analysis.5 3. Corpus data The corpus that serves as the data for the current study consists of informal interviews in English with forty Belgian native speakers of Dutch who are in second or third bachelor (age 19-26) at university or university college. Half of the interviewees study English Linguistics as a major subject at university (henceforth EL) and the other half study Commercial Sciences at a university college (henceforth CS). Hence, these two groups exhibit distinct learner profiles, viz. that of English linguistics students and that of English language students. The former have been extensively exposed to the target language, supposedly have a keen interest in the language and their aim is to attain a level of the language that approximates native speaker practice as closely as possible. The latter, on the other hand, study English as a minor yet compulsory course in their curriculum, their exposure to the language is less profound than that of students of English Linguistics, and their aim is of a solely instrumental nature. These populations seem excellently suited to verify the extent to which foreign language learners manage to acquire discourse markers, since pragmatic competence, which discourse markers are part of, is generally considered to develop to its optimal potential in the later stages of the foreign language 4 Kind of, kinda and sort of are taken together here. Aijmer (2002: 207-208) points out that they “seem to have the same meaning” and that the only notable difference between them is the extent to which they are used: in British English she observes sort of as being much more frequent than kind of. 5 Elsewhere I have provided a more elaborate enumeration of the (non-)discourse marker functions of the items at hand (Buysse 2010 and Buysse In press). [3] learning process (Barron 2000; Nikula 2002; Romero Trillo 2002; Pawlak 2010). Most studies investigating pragmatic items in the speech of foreign language learners focus solely on students of English Linguistics in tertiary education (e.g. Hays 1992; House 1996; Pulcini and Furiassi 2004; Gilquin 2008; Mukherjee 2009). However, as Kasper and Rose (2002: 219) point out, not all foreign language environments are the same, and each offers a different kind of learning opportunities for pragmatic strategies. The interviews were conducted by members of the teaching staff at the students’ institutions according to the format of the Louvain International Database of Spoken English Interlanguage (LINDSEI)6. They each last about fifteen minutes (with an average word count of 1,587) and follow the same pattern: the interviewee is asked to talk about a travel experience, hobbies, a book, etc., which leads to a conversation with the interviewer; every interview ends with a short picture-based storytelling activity. All interviewees volunteered to participate, which has not led to balanced gender ratios. Over two thirds of the EL corpus (14 out of 20) are made up of female speech, whereas the CS corpus is almost balanced for gender (11 female interviewees out of 20). In total the non-native interviews contain 63,494 words of interviewee speech (30,134 in CS and 33,360 in EL). The LINDSEI project also has a native speaker reference corpus (LOCNEC, Louvain Corpus of Native English Conversation)7, from which I selected a sample of 20 interviews with the same gender ratio as CS. In total my native speaker corpus (henceforth NS) comprises of 52,036 words of interviewee speech (2,602 on average). All native speakers were British students majoring in English Language and/or Linguistics at the University of Lancaster. 4. Results From Graph 1, which provides the relative frequency (as number of tokens per 1,000 words) for each discourse marker per sub-corpus, a clear divide between the operative and involvement discourse markers emerges. The former, so and well, show a higher incidence for CS and EL than for NS, whereas the latter, you know, like, kind of/kinda/sort of8 and I mean, are marginal in the two learner sub-corpora but relatively frequent in NS. Log-likelihood tests have been performed to measure statistical significance.9 The differences between EL and NS are all statistically significant at p<0.0001 (with loglikelihood ratios at 24.82 for so, 61.85 for well, 48.32 for you know, 106.42 for like, 154.16 for kind 6 For further details see: <http://cecl.fltr.ucl.ac.be/Cecl-Projects/Lindsei/lindsei.htm>. I am much indebted to the Centre for English Corpus Linguistics at the Université Catholique de Louvain-la-Neuve for granting me access to this corpus. 8 For the sake of completeness, these are the relative frequencies per 1,000 words for each form individually: kind of/kinda CS 0.33, EL 0.57 and NS 0.77; sort of CS 0.20, EL 0.33 and NS 5.03. 9 The log-likelihood ratio indicates the degree of certainty of an observed difference representing a true difference or being due to chance. A 100 per cent guarantee is unattainable but the level of significance (represented by the letter p) should never exceed 0.05 (p<0.05) in corpus linguistics, which means that we can be more than 95 per cent confident that the difference is real (McEnery et al. 2006: 55). Log-likelihood is especially useful if the expected frequency is lower than 5, in which case other tests, such as chi-square, are unreliable (Rayson and Garside 2000). 7 [4] of/kinda/sort of and 63.21 for I mean). The discrepancy between CS and NS achieves significance at p<0.01 for so, at p<0.001 for well and at p<0.0001 for you know, like, kind of/kinda/sort of and I mean (log-likelihood ratios at 7.21, 14.69, 161.11, 150.51, 181.20 and 75.42, respectively). 14.00 n tokens per 1,000 words 12.00 10.00 8.00 6.00 4.00 2.00 0.00 so well you know like kind of, etc. I mean CS 11.28 6.14 0.20 0.60 0.53 0.53 EL 12.98 8.45 1.65 1.20 0.90 0.75 NS 9.32 4.17 4.30 5.25 5.80 3.19 Graph 1 Relative frequency of each discourse marker per sub-corpus A comparison of the two learner sub-corpora reveals that CS frequencies are lower than EL frequencies for all discourse markers. Both CS and EL interviewees make elaborate use of so and to a lesser extent of well, but whereas in EL the involvement discourse markers still occasionally surface, these are virtually absent in CS. There is definitely a huge difference in incidence of you know between CS and EL, it being almost inexistent in the former whereas the latter interviewees make moderate use of the marker. Interestingly, that difference does not apply to I mean, which is even more frequent in CS than you know. Statistically significant differences between CS and EL are achieved for like at p<0.01, for well at p<0.001 and for you know at p<0.0001 (the log-likelihood ratios are 6.47 for like, 11.64 for well and 40.52 for you know); according to the log-likelihood test the differences for so, kind of/kinda/sort of and for I mean are not statistically significant (with ratios at 3.76, 3.02 and 1.18, respectively). It should be noted, however, that these numbers are on the whole small for the learner sub-corpora, which makes the results particularly vulnerable to distortion by individual interviewees’ performances. For instance, in both CS and EL two interviewees together account for more than half of all tokens of like in their respective sub-corpora. Similarly, in both of these sub-corpora one student produces over half of all I mean tokens. This phenomenon cannot be detected for discourse markers with a higher frequency in CS and EL (viz. so and well) nor for NS. [5] Compared to NS interviewees, EL subjects more heavily overuse so and well than CS participants, while their numbers for the other discourse markers more closely resemble NS frequencies, although they still far from approximate them. 5. Discussion The most striking observations from the quantitative overview are that (a) the students of Commercial Sciences who participated in the investigation hardly employ involvement discourse markers, awarding them final place in the ranking of the sub-corpora; and (b) the operative discourse markers are highly frequent in their speech, even more so than in that of the native speaker interviewees, yet less than in that of their EL peers. The following sections proffer a few tentative explanations for the situation sketched above. 5.1 Avoidance strategy Involvement discourse markers occasionally suffer from stigmatisation in English (Andersson and Trudgill 1990: 94), which exposes them to avoidance strategies in learner language. Although few would agree with the final part of their statement today, O’Donnell and Todd (1991), for instance, refer to you see, you know and I mean as “phrases which occur with varying frequency in informal speech, or with unskilful speakers” (1991: 69). Similarly, like has been described as a marker which is “intrusive […] and makes sentences seem disjointed to many listeners” (Underhill 1988: 234), and researchers have reported popular accusations of it being “redundant and without meaning” (Andersen 1998: 150) and “a mark of inarticulacy or word-finding difficulties” (Levey 2006: 415). Fox Tree (2007) claims that “[u]m/uh, you know, and like are often treated as a trio to avoid at all costs” (2007: 298), and MiskovicLukovic (2009) points out that kind of and sort of are “typical of informal style, and nonstandard language varieties” (2009: 602) and that “more often than not, these forms have borne the stigma of bad usage through prescriptivism and bias” (2009: 602). These claims are supported by attention that is occasionally paid to these markers in the public eye. Berkley (2002), for instance, has drawn up a website with tips that can help speakers avoid “verbal viruses” such as like, you know and sort of, and The Wall Street Journal has reported on attempts by schools to wipe out like from pupils’ speech (Petersen 2004). In a conversation with native speakers or with English teachers language learners will try to speak the target language “properly” (certainly if they know that their language is being monitored). For many that still involves avoiding all signs of informality, and as Aijmer (2002) notes about sort of, involvement discourse markers are “symptomatic of informal speech” (2002: 190), which may incite language learners, who are not highly confident about the appropriateness of linguistic forms in specific registers, to avoid them altogether. If foreign language learners were made aware, however, of the beneficial role such pragmatic devices can play, the results might look differently. Romero Trillo (2002) believes that “the development of pragmatic competence demands a (pseudo-)natural foreign language context that is often impossible [6] to produce in formal education” (2002: 770), a view shared by inter alia Kasper and Rose (2002) and Pawlak (2010).10 The linguistic input foreign language learners are exposed to is often unnatural and rarely focused to pragmatic items in spoken language (Fung and Carter 2007), and in advanced stages of the language learning process, such as in tertiary education, precedence is given to writing skills (Watts 2000). The interpersonal function of language is then often sacrificed in favour of the referential, because students are first and foremost expected to get messages across (Barron 2000). Therefore, the educational setting restricts the opportunities for foreign language learners to familiarise themselves with pragmatic devices such as involvement discourse markers. This certainly holds true for the CS interviewees in the corpus, and definitely more so than for their EL peers, since students of Commercial Sciences are merely scantily exposed to “real-life” spoken English in a classroom setting, let alone in their community. It has even been argued that a classroom setting does not spark a need to express relations foregrounded by involvement discourse markers (Nikula 2002), and hence students are hardly ever exposed to markers of such relations, be it in their mother tongue or in a foreign language. The language classroom would then become utterly unsuited as a locus to develop pragmatic competence. 5.2 Preference strategy To the best of my knowledge no stigmatisation has been reported for operative discourse markers. On the contrary, it would seem that because they are “linked to the mechanics of interaction” (Romero Trillo 2002: 782), they play a vital role as useful aids to attaining the main goal of the interaction, viz. to get a message across in a coherent fashion. Language learners may, therefore, not be reluctant to use them, because these linguistic items are rather uncontroversial in native speech. They have been acquainted with some of these markers (e.g. so) in their purely connective function since the early days of their language learning process, both in speech and writing, making it more convenient for them to acquire the perhaps less straightforward functions later on. Moreover, Lorenz (1999) and Anping (2002) have found that the operative discourse marker so is highly overused by language learners in written texts, suggesting that they certainly do not associate it with informality. Operative markers are abundantly present in teacher talk (Hellermann and Vergun 2007), and as a result language learners, even in the early stages of the acquisition process, seem to experience few problems mimicking operative discourse markers. Hence, students are constantly exposed to a limited set of textual discourse markers, which offers them a small inventory of such devices, which they then use time and again. In other words, they want to convey their message in a coherent way but (a) their paradigm of lexical choices is still limited, as a consequence of which they always resort to the same strategies; and/or (b) they want to make absolutely certain that their interlocutor interprets the discourse appropriately, to which end they supply an abundance of clues. Furthermore, the prototypical Dutch equivalents of so (i.e. dus) and well (i.e. wel, nou (ja), nu (ja)) are also highly frequent in spoken language without their being stigmatised. Because of this positive (or 10 Pawlak (2010) notes that mere exposure to the pragmatic devices of the target language is a necessary but insufficient condition for the acquisition of pragmatic competence in that language. What is vital is that learners pay attention to how the target language works in such environments, notice these devices and understand them. “[S]uch processes can be profitably fostered by formal instruction,” Pawlak (2010: 445) comments. [7] at least neutral) attitude towards well and so language learners may resort more to these discourse markers to perform functions which they share with involvement discourse markers. For instance, well, so and I mean can all be used as self-correction devices, although this function is more typical of I mean than of the other two markers. 5.3 Where the two strategies meet It is my contention that in the corpus under investigation the language learners craftily take advantage of the similarities between some operative and involvement discourse markers. Indeed, some functions of operative discourse markers may lean towards similar functions performed by an involvement discourse marker. Thus, the distinction between these two types of markers is somewhat too categorical, as it is based on the prototypical function rather than on the whole spectrum of uses of the discourse markers involved. If we now zoom in on so as a case in point, a picture of a notably versatile marker emerges, which prototypically acts as an operative discourse marker and is highly frequent in both the native and the learner sub-corpora under investigation. An outline of all ten functions than can be attested for so in the present corpus falls beyond the scope of this paper (for a detailed analysis see Buysse In press)11. All of these contribute to the coherence of the conversation, whether it be as an indicator of a relationship of ‘result’ or ‘inference’, or as a ‘floor-yielding’ device or as a marker of a shift back to a higher discourse unit. In some cases overlap can be established between a function of so and functions of involvement discourse markers. For instance, as examples (1) and (2) demonstrate, so can introduce a segment that elaborates on the prior segment by providing an example, specifying a vague or general statement or offering a parenthetical remark. (1) <B> no I've got my own car so <\B> <A> [oh yeah <\A> <B> [I just drive <X> <\B> <A> so that's quite easy [so you come whenever you: <\A> <B> [yeah I just commute whenever I want yeah <X> <\B> <A> oh yeah that's nice it's better than <\A> <B> [yeah <\B> <A> [I think <X> it's less expensive than [if you just took the bus because it's quite expensive <\A> <B> [yeah .. oh yeah .. and it's more convenient as well so . it's only . just just under half an hour <\B> <A> mhm <\A> 11 These are the ten discourse marker functions that can be attested for so: indicate a result, draw a conclusion, mark an evaluation, end a discourse sequence, hold the floor, introduce a part of the discourse, introduce the next sequence in a story or explanation, indicate a shift back to a higher unit of the discourse, introduce an elaboration and introduce a self-correction (cf. Buysse In press). [8] <B> from where I live so .. erm it's not too far <\B> (NS06; 16:00)12 (2) <B> […] well it’s very expensive to: [to do one of the= these courses <\B> <A> [yes I heard . yeah <\A> <B> and erm . so . normal people can’t pay can’t . pay . those courses <\B> <A> uhu <\A> <B> no it’s impossible for them so it’s about thi= no eight hundred euros for twelve days so <\B> <A> really <\A> <B> that’s very expensive [yes <\B> (EL17; 05:40) Although this is first and foremost an operative use of the discourse marker, in many of the elaborative uses of so another discourse marker, viz. I mean, would fit the same context and might even be idiomatically more appropriate. Fuller (2003) considers I mean a marker of “expansion, modification or clarification in a speaker’s contribution” (Fuller 2003: 190) and in a study of oral narratives González (2004) describes it as a marker of “reformulation, evaluation and addition of information whenever the narrator considers that his/her message requires further elaboration and/or expansion” (González 2004: 181). Example (3) illustrates the potential of I mean to mark explanatory segments in the present corpus. (3) <A> where does she live <\A> <B> she lives she lives in Newcastle <\B> <A> oh yeah mhm <\A> <B> .. <X> and and since I've come to university I've like . been a lot closer to her <\B> <A> mhm <\A> <B> I mean now it's only a hundred miles <\B> (NS05; 01:20) The ‘elaborative’ function of so can hardly be considered among its typical uses, given its low incidence in the native corpus, in which it accounts for only 6 per cent of all discourse marker tokens of so with a relative frequency of 0.58 tokens per 1,000 words (which compares with 1.00 in CS and 1.36 in EL). Moreover, it occupies a distant position vis-à-vis so’s ‘resultative’ core: rather than providing closure to a discourse sequence, it is aimed at continuing one, and rather than marking a shift to a superordinate level of the discourse (Schiffrin 1987), it marks the opposite. 12 The conventions used to transcribe these excerpts are those set for the LINDSEI project, and can be consulted at http://www.fltr.ucl.ac.be/fltr/germ/etan/cecl/Cecl-Projects/Lindsei/transnew.htm. The information in brackets refers to the interview (the code of the sub-corpus – NS, CS or EL – combined with the number of the interview in the sub-corpus) and the time (in minutes and seconds) at which the excerpt occurs in the interview. [9] In a similar vein, speakers may use so to signal upcoming self-repair, as is evidenced in both in the native and the learner sub-corpora, like in examples (4) and (5). (4) <B> […] I spent quite a lot of time at home on my own so I'm so used to being on my own that when with so many people around <\B> <A> mhm <\A> <B> it gets a bit a bit too claustrophobic so this year it was completely different living in town .. erm and I've actually really enjoyed it . because you've got the freedom of your own house and then you can so you've got some people in your house but then you can . sort of [go for <\B> <A> [go to your own room and <\A> (NS19; 06:11) (5) <B> er I really lo= it was about erm . well this girl and a guy and em they they’re in a relationship and er well eventually they break up and the girl decides she wants to: have her brain washed so she wants to have a brainwash and em . well then . it’s . really difficult to follow the movie but in the end it’s really like oh yeah that’s how it went […] <\B> (CS14; 00:28) This function of so is infrequent in the corpus, and certainly in the native corpus (with a relative frequency of 0.08 tokens per 1,000 words, which compares with 0.23 in CS and 0.30 in EL), and is also quite far removed from so’s core function. Much like for ‘elaborative’ so, such instances of self-repair warrant the use of I mean as an alternative to so as well. Fox Tree and Schrock (2002) inter alia describe I mean as a means to indicate “upcoming adjustments” (2002: 741), like in excerpt (6). (6) <B> but at the same time it’s . I think it’s a nice campus and it’s not I mean it could be a lot worse you could be surrounded by: lots of . at least you’ve got the trees the duck pond <\B> (NS07; 14:16) A final function of so that is worth touching upon in the light of the present discussion, exemplified in excerpts (7)and (8), is one in which so does not preface a segment and carries segment-final intonation (falling tone). Yet, an underlying proposition that is the result, conclusion or evaluation of what precedes can be conceived of and a corresponding segment can hence be (re)constructed if needs be. As such so (a) indicates that the speaker is willing to yield the floor, (b) marks an implicit ‘resultative’, ‘conclusive’ or ‘evaluative’ segment and (c) instructs the hearer to infer this segment from the prior co-text and/or the context. [10] (7) <A> do you find it’s a problem when you have nine o’clock lectures <\A> <B> I don’t have <begin laughter> any so <\B> <A> ah you’re lucky <\A> <B> yeah <end laughter> <\B> (NS16; 09:48) (8) <A> uhu uhu . em any films that you’ve seen recently <\A> <B> . erm well I hate films so <\B> <A> you hate [films <\A> <B> [yeah I hate films <\B> (CS16; 06:32) In these examples so could well be replaced by you know, because the latter “invites the addressee to complete the argument by drawing the appropriate inferences” (Jucker and Smith 1998: 196), as excerpt (9) illustrates. However, the additional capacity to instruct the hearer to take over the floor is not as poignantly present in you know as it is in so. In the present corpus, for instance, tokens of you know that lead to a turn shift are rare, even in the native speaker corpus. (9) <B> [but probably think about going into advertising <\B> <A> oh yeah <\A> <B> or . say like article writing <\B> <A> mhm <\A> <B> [something not <\B> <A> [for a newspaper <\A> <B> more like for a women’s magazine <\B> <A> oh yeah mhm <\A> <B> something that is . interesting but doesn’t take . so long and . you know <\B> <A> mhm <\A> <B> yeah <laughs> <\B> (NS03; 09:11) With a relative frequency of 1.63 tokens per 1,000 words, this non-prefatory function of so takes up 18 per cent of all discourse marker tokens in NS (compared with 2.82 in CS and 2.31 in EL), making it fairly frequent. It is also more proximal to so’s core function than the other two functions mentioned above, because it does end a discourse sequence and it introduces a result, conclusion or evaluation, albeit implicitly. On the other hand, it is highly interpersonal in its appeal to the hearer to make use of their shared background knowledge to complete the speaker’s utterance, and in its indication of the speaker’s desire to surrender the floor. [11] The frequencies for I mean and you know and related discourse markers (quoted in section 4) indicate massive underuse by language learners. The discussion above has indicated that there is some functional overlap between these two involvement discourse markers and the operative discourse marker so. Strikingly, the three functions of so concerned are clearly overused by the language learners in the corpus. It would seem that in the two learner sub-corpora the scope and frequency of non-core functions of so are extended, enabling the marker to take on prototypical functions of some involvement discourse markers, which these speakers seem to avoid, to a greater extent than native speakers. 5.4 Code-switching One could argue that the language learners in the corpus should already be familiar with devices in their mother tongue that are similar to the English involvement discourse markers. The question then remains, though, whether this leads to positive or negative transfer from the learners’ L1 to their interlanguage. (Belgian) Dutch has equivalents which closely resemble their English counterparts in that they are almost literal translations: weet je (wel) for you know, (ge)lijk for like (zoiets hebben van for quotative BE+like) and ik bedoel for I mean. For want of relevant academic investigations in this field, informal observations of students with the same profile as the participants of the present study may justify the claim that they use these markers with a high frequency in everyday conversation. However, that does not mean that these students are aware of that. Andersson and Trudgill (1990) point out that discourse markers “may pass unnoticed for a long period, but once they are discovered (or, rather, brought to our awareness) we hear them all the time” (1990: 94), which may lead to stigmatisation. Just like in English, these involvement discourse markers are often viewed negatively in Dutch and are on occasion publicly scoffed at. Some Dutch items similar to English discourse markers feature in columns and blogs that invariably evaluate these items negatively (e.g. Hautekiet 2008) and once in a while radio programmes have had listeners draw up lists of linguistic items that they find obnoxious. One such list13 ranks ik heb zoiets van (similar to quotative like) in first place and also features ik bedoel (identical to I mean). Thus, if native speakers of Dutch are aware of how these expressions are used in their mother tongue, they must also be familiar with how the public ‘ear’ tends to assess them. In an interview with a relative stranger in a foreign language, in which the interviewer can be regarded as ranking higher than the interviewee in the educational context (the former is a member of the teaching staff whereas the latter is a student), language learners may prefer to remain on safe ground and hence push the “involvement” aspects of the conversation into a secondary role. On the other hand, some code-switching can be attested in the language learners’ speech. Once in a while a linguistic item14 crops up that is borrowed from Dutch and fulfils the function of a discourse 13 This list was drawn up for the radio programme Dito, which was broadcast on the Flemish public network Radio 1 (VRT) on 11 March 2004. The list can still be consulted on some websites such as: http://www.kkunst.com/kk/20040309643.php (last accessed on 30 May 2010). 14 The status of these items is not always clear, and for want of research on these items, they cannot explicitly be dubbed “discourse markers”, and will be referred to as “(linguistic) items”. Note that pff may not even qualify for [12] marker such as the involvement discourse markers examined in this study. This is the case for ja, pff, goh, hè and allez (which is in its turn borrowed from French in the cross-regional spoken variety of Dutch in Flanders, known as “tussentaal”). Some examples may clarify their uses. In (10) the interviewee wants to minimise or at least qualify his prior statement with ja in much the same way as well or I mean could do in English. Pff in (11) performs a role often played by like and you know in English: it approximates a number. In (12) goh can be attributed a similar function as well as that of a stalling device, which allows the speaker to think of what to say next. Hè in (13) is a perfect match for you know in appealing to the hearer for understanding. In (14) and (15) allez, in its turn, signals a word-searching strategy similar to you know, and as a self-correction device such as I mean. (10) <B> […]15 I don’t I don’t want to teach or anything like that so that’s out of the question . and then and then I’d like to . be able to use my two languages I’ve studied that’s . obvious so . perhaps . go to: Sweden and . teach ja I don’t know not really teach but . yeah I really don’t have a clue . […] <\B> (EL02; 06:18) (11) <B> […] but there is no: . er the soup is can be: . pff . the the . fifth thing that . that <laughs> . that you: you get […] <\B> (CS17; 10:10) (12) <B> […] and . there you can eh <begin whisper> goh . <end whisper> yeah drive for er er one hundred miles without seeing er . one house or er . <\B> <A> uhu <\A> <B> something like that so: . it was a nice er .. experience <\B> (CS09; 01:17) (13) <B> […] but erm the stay over there wasn’t that expensive because . we . could eh stay there for a very cheap <\B> <A> uhu <\A> <B> er price because we had to to work over there also hè <\B> (EL20; 04:03) (14) <B> and if you . <\B> <A> uhu <\A> <B> must er allez walk faster than you can . actually in your tempo . that is that is not good <\B> the denomination “linguistic”, as it has more in common with the growl grr than with e.g. ja (English yes, yeah) or allez. 15 Excerpts have been abridged if certain passages are considered irrelevant to the illustrative purpose of the excerpt. [13] (CS18; 02:14) (15) <B> so it even . I wasn’t really good allez16 I couldn’t sleep after <begin laughter> I saw the documentary <end laughter> [it was very . <\B> (CS01; 02:18) As Graph 217 illustrates, CS interviewees use these Dutch items 4.05 times per 1,000 words, which is more than double the incidence of all English involvement discourse markers taken together (relative frequency 1.86; n=56). EL displays the mirror image, though: the Dutch items only surface 1.47 times per 1,000 words as opposed to 4.50 (n=150) for the English involvement discourse markers. Statistical significance is achieved at p<0.01 for pff, at p<0.0001 for goh, allez and the overall incidence of these markers (with log-likelihood ratios at 10.11, 15.86, 25.89 and 40.05, respectively).18 4.50 4.00 3.50 3.00 2.50 2.00 1.50 1.00 0.50 0.00 ja pff goh hè allez Overall CS 0.80 1.56 0.66 0.10 0.93 4.05 EL 0.54 0.72 0.09 0.03 0.09 1.47 NNS 0.66 1.12 0.36 0.06 0.49 2.69 Graph 2 Dutch markers in EL and CS Pff, allez and ja appear as the most popular items in the Dutch set. This may be a sign that the language learners, and CS interviewees in particular, experience problems common to a language learning situation, e.g. searching for the right phrase or self-correction, but cannot always manage to handle them with the appropriate pragmatic tools of the target language. Note, though, that the Dutch markers 16 The interviewee in (15) corrects the prior segment I wasn’t really good after she realises it is a literal translation from colloquial Dutch (ik was niet echt goed, meaning I wasn’t feeling all too well). 17 “NNS” represents the learner sub-corpus as a whole (i.e. the interviews of CS and EL combined). 18 The differences for ja and hè are not statistically significant because the respective log-likelihood ratios are at 1.58 and 1.26. [14] that are employed are not the object of stigmatisation in the Dutch language community, as opposed to others such as ik bedoel. Interestingly, the student who shows the lowest discourse marker frequency in the learner subcorpus (CS12) with only 9 tokens of so (relative frequency 5.21) and none of the other markers, reverts to ja, hè and allez 6 times (relative frequency 3.47), although he is undoubtedly aware of the inappropriateness of their use in English. The student with the highest discourse marker frequency in the learner corpus (CS14 with 56.35 discourse marker tokens per 1,000 words), on the other hand, does not use any Dutch items whatsoever. Obviously the numbers for these individual markers are fairly small, making these findings particularly vulnerable to distortion by performances of individual participants. 6. Conclusion This study has demonstrated that Dutch-speaking learners of English who have almost arrived at the end of their formal language learning process exhibit a clear preference for some English markers, notably those with an “operative” function (so, well), and neglect others, notably those with an “involvement” function (you know, I mean, sort of, …). The differences between the students of English Linguistics and Commercial Sciences are often subtle, but in general there is a tendency for the former to use these markers more frequently than the latter. On the whole, the language learner participants in the investigation take advantage of minor functional overlap between some operative and involvement discourse markers, in that the latter are typically avoided while the former take up some of their noncore functions to a larger extent than they do in native practice, thereby narrowing the inventory of pragmatic items in their speech. Some learners, particularly those studying Commercial Sciences, make up for this lack by inserting less controversial markers from their mother tongue into their English speech. In certain contexts a virtual absence of involvement markers in the language learners’ speech may hamper the effectiveness of their discourse as well as their opportunities to establish rapport with their interlocutor and to come across not only as a proficient speaker of English, but as a proficient speaker altogether. These observations clearly point at a potential handicap both for students who strive for near-native mastery of the language and for students whom the labour market expects to be able to, for instance, conduct effective business negotiations. By using discourse markers in a non-target-like fashion, or by code-switching, speakers may come across as disfluent, and run the risk of enlarging the distance between them and the target speech community (Hellermann and Vergun 2007), whereas speakers that are able to employ discourse markers adequately in the target language, will come across as fluent and confident (Sankoff et al. 1997). Thus, this investigation raises concerns that not only contribute to the current state of research in language acquisition, but that are equally relevant to matters of curriculum design and competence development. A solution is hardly in sight, though. Many have advocated that pragmatics should forge a place of its own in foreign language learning processes, because incorrect use or underuse of discourse markers by [15] non-native speakers may lead to misunderstandings (Aijmer 2002), but because these are habitually regarded as subservient to similar problems at the lexical, syntactical or morphological level (Hansen 1998), they are all too easily swept under the rug. After all, what is at stake for the language learner may not be as much miscommunication of her/his message as problems with how they are perceived by their interlocutors (Terraschke 2007; Gómez Morón et al. 2009). Thus, if language learners want to attain native-like proficiency in a target language, which is likely to be an aim for students of English linguistics, they have to demonstrate appropriate use of discourse markers (Hlavac 2006). If the aim of the language learning process is more modest, as can be expected for students of Commercial Sciences, the learners may still use these pragmatic devices to their advantage in, say, negotiations or job interviews, in which building rapport may be vital to achieving one’s goals. The crux of the matter seems to be twofold. First, one may wonder whether language education is altogether capable of forging a suitable environment for the acquisition of pragmatic devices. House (1996) as well as Bardovi-Harlig and Griffin (2005) remain convinced that pragmatic awareness and competence are developed gradually and specific classroom activity is needed to stimulate the process. Yet, recall that Romero Trillo (2002) and Pawlak (2010) have pointed out that (pseudo-)natural language environments are of the utmost importance in this respect, which classrooms are unlikely to be able to provide. In this light Llinares-García and Romero-Trillo (2008) suggest that Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL), in which courses other than language courses are taught in a foreign language, may offer a way out in that such an approach extends the language learning process beyond the language classroom, thereby expanding the span with which learners need to employ the foreign language. Although these authors demonstrate that pupils in a CLIL-setting in Spain are indeed exposed to more discourse markers in English than in a traditional classroom setting, their results equally show that (non-native) CLIL-teachers do not always use discourse markers appropriately. Moreover, Nikula (2005) shows that discourse markers are still used less in CLIL-classes than in L1-taught classes. This appears to be particularly the case for involvement markers due to a greater “interpersonal distance and a certain sense of artificiality” (2005: 45). Second, what is the ultimate goal of the language learning process? It may not be unjustified to wonder whether some of the precious time language teachers (at whichever level of education) get allocated should be devoted to the “subtleties” of the target language, such as pragmatic devices, if their pupils or students have not satisfactorily mastered the grammar of the language yet, and if the course schedule has to pay attention to other aspects than pure language acquisition as well (e.g. writing skills, presentation skills, literature). It seems that a thorough debate that involves all relevant actors (linguists, educators at different levels, curriculum designers and course materials developers alike) is long overdue. [16] References Aijmer, K. 2002. English Discourse Particles. Evidence from a Corpus (Studies in Corpus Linguistics 10). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Amfo, N. A. A. 2007. Explaining connections in Akan discourse. Languages in Contrast 7(2). 185-202. Andersen, G. 1998. The pragmatic marker like from a relevance-theoretic perspective. In A. H. Jucker and Y. Ziv (eds.), Discourse Markers. Descriptions and Theory (Pragmatics & Beyond New Series 57), 147-170. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Andersson, L.-G. and P. Trudgill. 1990. Bad Language. London: Penguin Books. Anping, H. 2002. On the discourse marker so. In P. Peters, P. Collins and A. Smith (eds.), New Frontiers of Corpus Research. Papers from the Twenty First International Conference on English Language Research on Computerized Corpora Sydney 2000, 41-52. Amsterdam/New York: Rodopi. Bardovi-Harlig, K. and R. Griffin. 2005. L2 pragmatic awareness: Evidence from the ESL classroom. System 33. 401-415. Barron, A. 2000. Acquiring ‘different strokes’. A longitudinal study of the development of L2 pragmatic competence. German as a Foreign Language 2. 1-29. Bazzanella, C. 1990. Phatic connectives as interactional cues in contemporary spoken Italian. Journal of Pragmatics 14(4). 629-647. Beeching, K. 2002. Gender, Politeness and Pragmatic Particles in French (Pragmatics & Beyond New Series 104). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Berkley, S. 2002 (7 February). How to cure the “Verbal Virus”. A five-step treatment plan. Retrieved from http://www.school-for-champions.com/speaking/verbalvirus.htm (last accessed on 30 May 2010). Buysse, L. 2010. Discourse markers in the English of Flemish university students. In I. Witzcak-Plicieka (ed.), Pragmatic Perspectives on Language and Linguistics (Vol. 1: Speech Actions in Theory and Applied Studies), 461-484. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. Buysse, L. In press. Discourse Marker So in Native and Non-Native Spoken English (unpublished doctoral dissertation). Gent: Universiteit Gent. Fischer, K. (ed.). 2006. Approaches to discourse particles (Studies in Pragmatics 1). Amsterdam: Elsevier. Fox Tree, J. E. 2007. Folk notions of um and uh, you know, and like. Text & Talk 27(3). 297-314. Fox Tree, J. E. and J. C. Schrock. 2002. Basic Meanings of you know and I mean. Journal of Pragmatics 34(6). 727-747. Fraser, B. 1999. What are discourse markers. Journal of Pragmatics 31(7). 931-952. Fuller, J. M. 2003. Discourse marker use across speech contexts: A comparison of native and non-native speaker performance. Multilingua 22. 185-208. Fung, L. and R. Carter. 2007. Discourse markers and spoken English: Native and learner use in pedagogic settings. Applied Linguistics 28(3). 410-439. Gilquin, G. 2008. Hesitation markers among EFL learners: Pragmatic deficiency or difference? In J. Romero-Trillo (ed.), Pragmatics and Corpus Linguistics: A Mutualistic Entente (Mouton Series in Pragmatics 2), 119-149. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. [17] Gómez Morón, R., M. Padilla Cruz, L. Fernández Amaya and M. de la O Hernández López. 2009. Incorporating pragmatics to foreign/second language teaching. In R. Gómez Morón, M. Padilla Cruz, L. Fernández Amaya and M. de la O Hernández López (eds.), Pragmatics Applied to Language Teaching and Learning, xii-xlii. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. González, M. 2004. Pragmatic Markers in Oral Narrative: The Case of English and Catalan (Pragmatics & Beyond New Series 122). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Hansen, M.-B. M. 1998. The Function of Discourse Particles. A Study with Special Reference to Spoken Standard French (Pragmatics & Beyond New Series 53). Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Hautekiet, J. 2008 (11 February). Weg met ‘Zoiets hebben van…’! Taalschrift. Tijdschrift voor Taal en Taalbeleid. Retrieved from http://taalschrift.org/discussie/001718.html (last accessed on 30 May 2010). Hays, P. R. 1992. Discourse markers and L2 acquisition. In D. Staub and Ch. Delk. (eds.), The Proceedings of the Twelfth Second Language Research Forum. April 2-5, 1992. Michigan State University, 24-34. Michigan: Papers in Applied Linguistics. Hellermann, J. and A. Vergun. 2007. Language which is not taught: The discourse marker use of beginning adult learners of English. Journal of Pragmatics 39(1). 157-179. Hlavac, J. 2006. Bilingual discourse markers: Evidence from Croatian-English code-switching. Journal of Pragmatics 38(11). 1870-1900. House, J. 1996. Developing pragmatic fluency in English as a foreign language. Routines and metapragmatic awareness. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 18(2). 225-252. Jordà, M. P. S. 2005. Pragmatic production of third language learners of English: A focus on request acts modifiers. International Journal of Multilingualism 2(2). 84-104. Jucker, A. H. and S. W. Smith. 1998. And people just you know like 'wow': Discourse markers as negotiating strategies. In A. H. Jucker and Y. Ziv (eds.), Discourse Markers. Descriptions and Theory (Pragmatics & Beyond New Series 57), 171-201. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Kasper, G. and S. Blum-Kulka. 1993. Interlanguage Pragmatics: Introduction. In G. Kasper and S. BlumKulka (eds.), Interlanguage Pragmatics, 3-17. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Kasper, G. and K. R. Rose. 2002. Pragmatic Development in a Second Language. Oxford: Blackwell. Levey, S. 2006. The sociolinguistic distribution of discourse marker like in preadolescent speech. Multilingua 25(4). 413-441. Llinares-García, A. and J. Romero-Trillo. 2008. Discourse markers and the pragmatics of native and nonnative teachers in a CLIL corpus. In J. Romero-Trillo (ed.), Pragmatics and Corpus Linguistics: A Mutualistic Entente (Mouton Series in Pragmatics 2), 191-204. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. Lorenz, G. 1999. Learning to cohere: Causal links in native vs. non-native argumentative writing. In W. Bublitz, U. Lenk and E. Ventola (eds.), Coherence in Spoken and Written Discourse: How to Create It and How to Describe It (Pragmatics and Beyond New Series 63), 55-75. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Maschler, Y. 1998. Rotsè lishmoa kéta? ‘wanna heir something weird/funny [lit. ‘a segment’]?: The discourse markers segmenting Israeli Hebrew Talk-in-interaction. In Jucker and Ziv (eds.). Discourse [18] Markers. Descriptions and Theory. Pragmatics & Beyond New Series 57. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. 13-59. McEnery, T., R. Xiao and Y. Tono. 2006. Corpus-Based Language Studies. London/New York: Routledge. Miskovic-Lukovic, M. 2009. Is there a chance that I might kinda sort of take you out to dinner?: The role of the pragmatic particles kind of and sort of in utterance interpretation. Journal of Pragmatics 41(3). 602-625. Mukherjee, J. 2009. The grammar of conversation in advanced spoken learner English: Learner corpus data and language-pedagogical implications. In K. Aijmer (ed.), Corpora and Language Teaching (Studies in Corpus Linguistics 33), 203-230. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. Müller, S. 2004. Well you know that type of person: Functions of well in the speech of American and German students. Journal of Pragmatics 36(6). 1157-1182. Müller, S. 2005. Discourse Markers in Native and Non-native English Discourse (Pragmatics & Beyond New Series 138). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Nikula, T. 2002. Teacher talk reflecting pragmatic awareness: A look at EFL and content-based classroom settings. Pragmatics 12(4). 447-467. Nikula, T. 2005. English as an object and tool of study in classrooms: Interactional effects and pragmatic implications. Linguistics and Education 16(1). 27-58. O’Donnell, W. R. and L. Todd. 1991. Variety in Contemporary English (second edition). London: Harper Collins Academic. Pawlak, M. 2010. Teaching and learning pragmatic features in the foreign language classroom: Interfaces between research and pedagogy. In I. Witzcak-Plicieka (ed.), Pragmatic Perspectives on Language and Linguistics (Vol. 1: Speech Actions in Theory and Applied Studies), 439-460. Newcastle-uponTyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. Petersen, A. 2004 (4 February). It’s, like, taking over the entire planet. Young adults abandon the speech crutch “like”. The Wall Street Journal, p. 4. Pons Bordería, S. 2006. A functional approach to the study of discourse markers. In K. Fischer (ed.), Approaches to discourse particles (Studies in Pragmatics 1), 77-99. Amsterdam: Elsevier. Pulcini, V. and C. Furiassi. 2004. Spoken interaction and discourse markers in a corpus of learner English. In A. Partington, J. Morley and L. Haarman (eds.), Corpora and Discourse (Linguistic Insights 9), 107123. Bern: Peter Lang. Rayson, P. and R. Garside. 2000. Comparing corpora using frequency profiling. In A. Kilgarriff and T. Berber Sardinha (eds.), Proceedings of the Workshop on Comparing Corpora. Held in Conjunction with the 38th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. 7 October 2000, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Hong Kong, 1-6. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Romero Trillo, J. 2002. The pragmatic fossilization of discourse markers in non-native speakers of English. Journal of Pragmatics 34(6). 769-784. Romero-Trillo, J. 2007. Adaptive management in discourse: The case of involvement discourse markers in Spanish conversations. Catalan Journal of Linguistics 6. 81-94. [19] Sankoff, G., P. Thibault, N. Nagy, H. Blondeau, M.-O. Fonollosa and L. Gagnon. 1997. Variation in the use of discourse markers in a language contact situation. Language Variation and Change 9(2). 191-217. Schiffrin, D. 1987. Discourse Markers (Studies in Interactional Sociolinguistics 5). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Schourup, L. 1999. Discourse markers. Tutorial overview. Lingua 107. 227-265. Terraschke, A. 2007. Use of general extenders by German non-native speakers of English. IRAL 45(2). 141-160. Underhill, R. 1988. Like is, like, focus. American Speech 63(3). 234-246. Watts, S. 2000. Teaching talk: Should students learn ‘real German’? German as a Foreign Language 1. 64-82. Wouk, F. 1999. Gender and the use of pragmatic particles in Indonesian. Journal of Sociolinguistics 3(2). 194-219. [20]