Talar Fractures and Dislocations Description Talar fractures and

advertisement

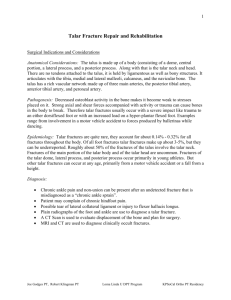

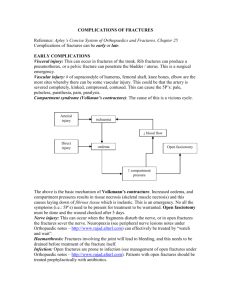

Talar Fractures and Dislocations Description Talar fractures and dislocations are relatively uncommon orthopaedic injuries resulting from high energy impacts such as severe motor vehicle accidents or falls from significant height. Their importance lies in the fact that the talus is integral to weight bearing in humans and the propensity for complications, such as avascular necrosis of the talus body. Structure and Function The talus is an architectural masterpiece. Body weight is distributed through the tibia to the superior surface of the talus. Anatomically, the talus is composed of: 1. Body - consists of dome (articulates superiorly with tibial plafond), central portion, posterior process (consisting canal for the flexor hallicus longus tendon) and lateral process. The body has relatively poor blood supply which runs distal to proximal. 2. Neck – most commonly fractured zone. This area has the main blood supply (via sinus tarsi) to the talar body, thus fracture displacement at the talar neck can result in avascular necrosis of the talar body. 3. Head – articulates with navicular providing abduction and adduction movements at the talonavicular joint. Epidemiology Talar fractures are rare injuries, representing 0.1 – 0.85% of all fractures (Fortin & Balazsy, 2001). Significant force of impact is required for fracture formation. Clinical Presentation Fracture of the talar neck results from hyperdorsiflexion of the ankle whereby the neck is pushed violently against the anterior edge of the tibia. More severe force may result in fracture dislocations. Fractures of the body are usually the result of a compression injury such as fall from significant height. Classically the patient presents with a painful and swollen foot with crepitus. There is pain on weight-bearing. Displaced fractures may present with obvious deformity or skin tenting (a dangerous sign). Talar neck fractures are popularly classified using the Hawkins (1970) classification system, which allows for treatment options and prognostic value (risk of AVN). This is a controversial system because lack of treatment distinction between Types II-IV. Students are advised to appreciate distinction between displaced and non-displaced as this influences management. Hawkins Type I Type II Description Nondisplaced Displaced with subluxation or dislocation of subtalar joint Risk of AVN (%) 0-15 20-50 Treatment No reduction needed Controversial (Closed Reduction vs ORIF) Type III Type IV Displaced with dislocation of body from ankle mortise Displaced with subluxation or dislocation of the talonavicular joint 20-100 ORIF ORIF Fracture of talus head: Uncommon, usually involves talonavicular joint. Fracture of talus body: Uncommon, often displaced, best visualised using CT imaging. Fracture of lateral and posterior processes: Usually associated with ankle ligament strains. Red Flags Some clinical red flags include neurovascular compromise and tenting of the skin. Tenting is a poor sign due to risk of skin necrosis if reduction is delayed. Differential Diagnosis Clinical presentation (painful and swollen foot) and the fact that severe impact required for injury, means that other foot and ankle injuries such as soft tissue injuries and ankle fractures need to be excluded. Specifically, subtalar dislocation and total dislocation of the talus should be excluded. Objective Evidence Talus fractures are commonly missed on foot and ankle series. First line imaging (in most cases) is anteroposterior, lateral and oblique x-rays. The canale view provides the best view of talar arch. CT imaging allows for better definition of the fracture and associated soft tissue injuries. MRI is particularly useful in the diagnosis of osteochondral fractures of the talus which usually occur on the lateral part of the dome of the talus. AP view. Talar body fracture, sagitally orientated. There is also disruption of the tibiotalar and subtalar joints. AP view. Lateral process fracture. LP= Lateral Process. LM= Lateral Malleolus. CT scan. Fracture of the lateral and posterior process of talus, which are associated with talar body fracture. Risk factors and Prevention Talar fractures and dislocations are the result of high-energy trauma. Treatment Swelling is a major problem in talar fractures and dislocations – it causes pain and makes clinical examination difficulty. Consequently, swelling should be addressed with realignment, splinting and elevation of the foot (Solomon, Warwick, & Nayagam, 2010). Ice packs and intermittent foot compression can be considered. Once fracture pattern is identified, definitive treatment should begin. Undisplaced fractures: 0 week – split below knee plaster applied. Once swelling subsides, replaced by complete cast with foot plantar flexed. Non-weightbearing. 4 weeks – remove plaster, imaging studies, apply new cast and have patient for gradual weightbearing. Physiotherapy. 8 - 12 weeks – Splintage discarded and return to normal function. Displaced fractures of the neck: All Hawkins Type II-IV fractures require reduction. If skin tenting, reduction acquires more urgency due to risk of skin necrosis. Reduction must be perfect to ensure subtalar joint mechanically sound and to reduce the propensity for avascular necrosis. Type II – closed manipulation under general anaesthesia can be attempted as first line. Apply nonweight bearing below knee cast for 4 weeks. Usually at 8-12 weeks there is evidence of union at which time the patient can be made weightbearing. Closed reduction often fails and ORIF is required. Consequently, many orthopods advise ORIF as first line treatment. Anteromedial incision is made and fracture manipulated into place. Fracture fixed with two K-wires or lag screw. Post-operatively, below knee non-weightbearing cast till 8-12 weeks. Type III-IV: Require ORIF. Approach depends on fracture pattern and position of displaced fragments. Post-operatively swelling allowed to reduce, then same as for Type II. Displaced Fractures Body: Displaced fractures with dislocation of adjacent joints should be accurately reduced by ORIF. Prognosis is poor with considerable incidence of malunion, joint incongruity, avascular necrosis and secondary osteoarthritis. Dispalced Fractures Head and Talar Processes: ORIF if fragments large enough, excision if fragments small and highly comminuted. Outcome Talar neck fractures are associated with high complication rates. Elgafy et al (2000) retrospectively reviewed 58 talus fractures followed for a period of 30 months. In their study, 53.3% developed subtalar arthritis, 25% had ankle arthritis and 16.6% developed AVN (Elgafy, Ebraheim, Tile, Stephen, & Kase, 2000). The incidence of AVN was much more common in Hawkins Type II and III fractures. Vallier et al (2004) reviewed data on 60 patients with talar neck fractures treated with ORIF, followed for a period of 36 months post-operatively. Osteonecrosis had a high occurrence rate (49% of patients), with or without collapse of the talar dome (Vallier, Nork, Barei, Benirschke, & Sangeorzan, 2004). Additionally the study found that there was no correlation between time to surgical fixation and the development of osteonecrosis (Vallier, Nork, Barei, Benirschke, & Sangeorzan, 2004). A limitation of both studies is the small sample size. Vallier et al (2004) had complete radiographic data on only 39 patients. Vallier et al (2004) recommend proceeding with surgical fixation after soft tissue swelling subsides to minimise soft tissue related complications. Miscellany and Skills There still remains a lot to be discovered in this area of orthopaedics. Considering that there is no difference in treatment between Hawkins II-IV, medical students should be stressed to appreciate the difference between displaced and non-displaced talar neck fractures. The key points here are that talar neck fractures are rare and difficult to identify on plain imaging for the unskilled eye. However, due to the important nature of the talus bone and the propensity for complications, it is important that medical students appreciate the significance of the talus and the need to screen for such fractures. Key Terms – Talus; Talar neck fractures; Hawkins; ORIF Elgafy, H., Ebraheim, N., Tile, M., Stephen, D., & Kase, J. (2000). Fractures of the talus: experience of two level 1 trauma centers. Foot Ankle International , 1023-1029. Fortin, P. T., & Balazsy, J. E. (2001). Talus fractures: Evaluation and Treatment. Journal of American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons , 114-127. Solomon, L., Warwick, D., & Nayagam, S. (2010). Apley's System of Orthopaedics and Fractures. London: Hodder Arnold. Vallier, H. A., Nork, S. E., Barei, D. P., Benirschke, S. K., & Sangeorzan, B. J. (2004). Talar neck fractures: Results and Outcomes. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery , 1616-1624.