an extensive biography and Q&A

advertisement

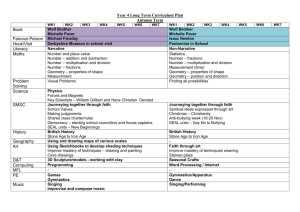

MICHELLE PAVER Biography & Interview Peter Cox / Redhammer BIOGRAPHY M ichelle was born in 1960 in Nyasaland (now Malawi), where her South African father ran the tiny Nyasaland Times, and her Belgian mother wrote a weekly gossip column. But the days of genteel colonial society were numbered, and in 1963 the family moved to England. Michelle was educated in Wimbledon and at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford. There she read Biochemistry and also made her first serious attempts at writing: two Mills & Boon-type novels, written in a matter of weeks and summarily rejected (‘with good reason!’ she says), followed by a couple of children’s fantasy novels - also rejected, although more encouragingly. By then she was in the grip of the writing bug. She even managed to ditch the usual final-year laboratory project in favour of a written thesis: simply because, as she admits, ‘I'd stumbled on a great story: Soviet genetics driven underground by an illiterate croney of Stalin's. How could I resist?’ That got her a First, but by then she'd decided against a career in science. ‘I knew I wanted to write, but I didn't think I'd be able to make a living at it, so I looked around for a day job: something that would pay the bills while giving me time to write. Like an idiot, I chose the Law. It was a spur-of-the-moment decision. One rainy afternoon I was leafing through a careers brochure when I came across an article on being a solicitor. I thought, ‘that'll give me a few years' breathing space before it gets too demanding, so why not?’’ Of course it didn't turn out quite like that. Michelle qualified as a solicitor with a big City firm, and was soon up to her neck in big-ticket scientific litigation. Multinational drug companies slugging it out over who owned which gene; tobacco companies battling to defend themselves against plaintiffs dying of cancer. ‘There were times,’ she says, ‘when I didn't exactly feel on the side of the angels.’ Outwardly she was a success, having been made a partner five years after qualification. But the strain of all-night meetings and missed weekends was beginning to tell. Then in 1996 her father died, and that proved a wake-up call. ‘I realized that I wasn't doing what I really wanted to do, and although I was earning lots of money, I'd never have time to spend it. So I decided to negotiate a year off, to get myself sorted out. At the time, that was unheard-of in a City firm. They didn't even have a sabbatical policy. But I told myself that if they said no, I'd quit anyway, and that at least gave me the courage to ask. To my astonishment, they PAVER 1 said yes.’ Michelle spent 1997 travelling around Peru, Ecuador, South Africa, France, and the States, and finishing the first draft of WITHOUT CHARITY… ‘It's no coincidence that the story is all about seizing the moment. And it's also personal in another way, as it's partly set during the Boer War, which bankrupted my father's family. Although they were fiercely loyal to the Crown, they fell victim to the scorched earth policy when the British burnt most of their farms - by mistake! To my surprise, researching the book in South Africa turned out to be a pretty emotional experience. I kept wishing my father could have been with me. For example, when I visited the little farming town of Reitz, where the early Pavers settled in the nineteenth century, I found a portrait of my great-grandfather, the second mayor, hanging in the Town Hall, and even a ‘Paver Straat’.’ After her year off Michelle returned to the City, and realized on the very first day that it was a mistake… ‘There were three thousand e-mails clogging up my computer, and all I could think about was WITHOUT CHARITY. So I sent the manuscript off to a publisher, and then, without waiting for a reply, I resigned. A couple of months later, Transworld offered me a publishing contract - to my relief!’ WITHOUT CHARITY was selected by WH Smith (Britain’s biggest booksellers) as one of a handful of debut novels to be awarded their Fresh Talent accolade for 2000. Since then, Michelle has worked as a writer full-time. She lives in Wimbledon, and is neither married nor divorced. PAVER 2 Michelle's second book, A PLACE IN THE HILLS, tells two intertwined love stories that take place two thousand years apart… ‘I've always been passionate about ancient Rome, and I've always loved the idea of a contemporary character having a real connection with someone in the distant past. But why a love story? Well, in a way, I was trying to prove to myself that great love - true, self-sacrificing, altruistic love - can actually exist. To my surprise, I ended up convincing myself. Although what the reader will think about that is up to them.’ A PLACE IN THE HILLS was short listed for the 2002 Parker Pen Romantic Novel of the Year award. Her third book, THE SHADOW CATCHER, is the first in the EDEN trilogy… ‘It's set in colonial Jamaica,’ she says, ‘at a crucial period of transition: the slaves had been freed, the great sugar plantations were in decay, and there was an incredible sense of uncertainty. The tone of the story is what I'd call Caribbean Gothic. With my background I'm obviously drawn to themes of the Empire under threat, but the EDEN trilogy is as much about class, and the position of women in Victorian society.’ ‘Researching it was an experience in itself. In Jamaica, everyone seems to know everyone else, so if you've got family there, as I have (this time on my mother's side), you're instantly connected to what seems like half the population. For example, my cousin has a farm on the north coast, and his wife's friend's mother is a leading light in the Jamaica Historical Society, and she's married to the grandson of a Victorian vicar who just happened to write the seminal work on Jamaican magic back in the 1890s, and so it goes on...’ In 2003, Michelle started work on an idea for a series of six books that had been brewing ever since childhood. Set in prehistoric, hunter/gatherer times, in a world of dark enchantment, menace and superstition, the stories revolve around a boy - and his wolf companion - growing up, fighting for survival and unleashing a powerful magic… PAVER 3 ‘CHRONICLES OF ANCIENT DARKNESS is my way of achieving what I used to dream about when I was ten years old: to run with the wild wolves in the prehistoric Forest. ‘As a child, my passions were myths, animals, and how people actually lived in the distant past. I read and re-read Roger Lancelyn Green's tales of the Norsemen and the Ancient Egyptians. I pored over pictures of Stone-Age hunters scraping hides and knapping flints. I bought a copy of Culpeper's Herbal, and dug up my parents' lawn to grow outlandish medicinal plants. And I read everything I could find on animal behaviour: especially about wolves. (Wolf researchers such as David Mech, Michael Fox and Lois Crisler quickly became my heroes.) As I grew older, I managed to do a fair bit of travelling in out-ofthe-way places: Iceland, Norway, South America, the Rockies; often hiking on my own so as not to dilute the experience. I worked as a volunteer on a wildlife survey in the Carpathian Mountains, where I heard red deer bellowing in rut, and found fresh wolf-tracks calmly crossing my own, and nearly lost my nerve when I came across an enormous pile of steaming dung. (Bear? Bison? I didn't hang around to find out.) Gradually I realised that the old enthusiasms hadn't gone away; they'd just broadened and taken root. And when I had the idea for CHRONICLES OF ANCIENT DARKNESS, it all came together!’ And when I had the idea for CHRONICLES OF ANCIENT DARKNESS, it all came together. `In fact, though, I'd had the basic idea back at University, in the early 80s. I'd even written it: a story about an orphaned boy struggling to survive with his beloved wolf-cub. But I'd set the story in the ninth century, and the historical context kept getting in the way. So I put the manuscript in a box-file and shoved it to the back of a cupboard. For twenty years the idea of the boy and the wolf simmered away in my subconscious. It nagged me. I really wanted to write it. But I knew I hadn't found the right context. Then, I unearthed the box-file and took another look at my twenty-year-old notes. The answer just leapt out at me. This isn't a story about history. It's about prehistory. As soon as I realised that, everything fell into place. PAVER 4 To learn what the Clans of Torak's world use for weapons, clothes, food and shelter, I studied the Mesolithic peoples of Northern Scandinavia, including the Maglemosians, and the Ertebølle and Kongemose cultures. I also borrowed from the more recent past: from the survival strategies of traditional Inuit and Native American peoples, and many others. Similarly, in trying to understand how my hunter-gatherers actually think, I've been guided by anthropology: not only that of the Inuit and the Native American peoples, but also the Ainu of Japan and the Sami of Lappland; the San, the Eboe and the Kwaio of Africa, and the Aborigines of Australia. CHRONICLES OF ANCIENT DARKNESS has now been sold into every major publishing market worldwide, setting records in many of them. PAVER 5 INTERVIEW * What made you start writing? I wrote my first story when I was five: a rip-roaring adventure about an escaped Tyrannosaurus rex and a rabbit called Hamish. I don't remember what made me start writing stories: it was just something I knew I wanted to do, as soon as I could read. * What did you find the hardest thing to do? Simply to keep writing - day after day, week after week, and year after year, when I had no idea whatsoever if I'd ever get published. I used to get up very early in the morning in order to put in a couple of hours before going to the office, and sometimes I'd sit at my desk listening to the dawn chorus starting up outside, and ask myself if I was completely crazy, wasting my time like this? But the thought of chucking it in - of not writing - was just too bleak to contemplate. So I'd make another mug of coffee and shuffle back to my desk, and get on with it. * How would you describe the ‘writer's life?’ Marginalized, solitary, sometimes worryingly lonely, but above all, not in the slightest bit grown-up. I sp * Do you miss the excitement/pressure of the lawyer's boardroom? When I heard this question with. for I was the afirst litigator time, for I laughed 13 years, so hard and to that begin I nearly with,fell it was off my chair! This may s wonderful to be learning the ropes of what was then still very much a man's job; and then there was all the excitement of going for partnership; and then - ? Well, then there was ‘more of the same’. More big-ticket cases about drugs and tobacco and disposable nappies (oh yes, I was one of the doyennes of the ‘Nappy Wars’ litigation of the 80s and 90s - which just about says it all); more horribly urgent ‘deal with it yesterday’ faxes from Japan and the States and wherever, more postponed holidays, and more weekends lost to work. * What were your favourite books when you were younger? As a small child, I adored Tove Jansson's Moomin books (I wrote to her once, and got a lovely long letter back, all about PAVER 6 Moomins' dietary requirements), and then it was Tolkien, and Alan Garner's Elidor and The Owl Service; John Gordon (especially The Giant Under the Snow); all of Roger Lancelyn Green's masterly re-tellings of the myths - Greek, Norse, Egyptian; and any anthology of ghost stories that I could get my hands on: M.R. James, of course, and E. Nesbitt. I was ten when I first read her Man-size in Marble, and it kept me awake in a cold, terrified sweat, for hours. * Who or what has influenced you? That's really hard to answer, because some of the most powerful influences are the hardest to spot. But I'd certainly name my mother as a strong influence because she never cuts corners, and always does her best at anything she sets her hand to. I remember once when I was about seven, I got the part of the queen in the school play, so I needed a crown. My mother got to work that night, and didn't just come up with the usual foil-covered cardboard zig-zags: she also made a dome of red velvet to fit inside, and an `ermine' trim of cotton-wool and black fluff. With an example like that, it's no wonder that I grew up a little finicky when it comes to details! * Where did you grow up, how did this place influence you? I grew up in Wimbledon, south-west London, and I don't think it did influence me very much, because I had a happy childhood, and in my experience happiness doesn't tend to provide easily identifiable `influences'. Adolescence, however, was another matter. I was overweight, spotty, and generally obnoxious. I hated everything, and that included Wimbledon, which was then just starting to get a bit more upmarket, so everyone suddenly seemed to be very thin and sure of themselves and fashionably dressed. That did influence me, enormously. For one thing, I stayed in and read everything I could lay my hands on. For another, I experienced at first hand what it's like to feel lonely, unlovely and generally miserable, for what felt like a very long time. It all proved pretty helpful when I started writing novels. * If you could invite five people alive or dead to dinner, who would they be and what would you eat? Charles Darwin, Gaius Valerius Catullus, Sir James Frazer, Anthony Trollope, and Jane Austen. I'd be far too intimidated to open my mouth, but I'd love to PAVER 7 meet this lot, so what the hell. As for food - I definitely would not want to be responsible for the menu. Instead I'd take them all to the Ivy - and with any luck, Catullus would end up choosing for everyone. * Who are your favourite authors? As you've probably guessed, Jane Austen and Anthony Trollope are high on the list. Also Kipling, Ray Bradbury, Keats, Henry James, and Edith Wharton. I also love the ghost stories of MR James. And I wouldn't want to leave out Homer, Catullus or Propertius. Since I became a full-time novelist, I tend to read much less modern fiction than I used to, because it's awfully difficult to avoid making comparisons with one's own work, and that's the opposite of relaxing. For example, if I think the author writes badly, I get discouraged because it still got published anyway, so maybe that's what people really want, etc, etc. And if he or she writes well, I just get discouraged, plain and simple. * Are you as bold in real life as you are in your writing? I don't think I'm anything like as bold in real life! I loathe confrontation, and tend to be much more of an observer than a participator. But I suppose one might say the same of a lot of writers. * How do you go about constructing your story lines? Do you know what will happen before you begin writing the first page or do things develop as you go along? I'm a typical Virgoan, that thereis will to say, come extremely a pointorderly, when Iwith have a passion to change for planning the plot and lists - so yes, I d because the characters are acting up... and so it goes on. * Did you conduct your research? What were your sources? Have you actually travelled to the sites you describe in your books? For the historical research, I find that the gold standard is the wonderful British Library, where you can unearth the most amazing contemporary sources if you know where to look. For example, for my first book Without Charity, I found the privately published memoirs of a British field surgeon from the Boer War, which contained a wonderfully vivid (and very funny) account of a small field PAVER 8 hospital in the veldt, with lots of unexpected detail. As regards what you might call the `location' research, there's no substitute for actually going there. For A Place in the Hills, this included a freezing week spent in a rented cottage in a tiny French Pyrenean village. * When did one book grow into the six books of CHRONICLES OF ANCIENT DARKNESS? Almost immediately. I quickly realized that Torak's story doesn't end with WOLF BROTHER: that's just the beginning. And last summer, during a heat-wave, I spent a wonderful week sitting in my small, overgrown garden, while the whole of CHRONICLES OF ANCIENT DARKNESS just unfolded before me. It felt as if it had always been there; as if I was merely discovering it. For a writer, that doesn't happen very often, but when it does, it's wonderful - and also slightly spooky. * How did you make the character of Wolf so real? Since I was a child, I've always read everything I could find about wolves, so I know a fair bit about them. But to get to know Wolf, I had to get inside his mind: to see the world through his eyes, and more importantly, through his nose and ears! From the start I knew that when he first meets Torak, Wolf mistakes him for another wolf, because of the strip of wolf skin which Torak wears on his jerkin. With that in mind, I began to see how Wolf would perceive Torak, with his complicated forepaws and his furless underpelt - and his puzzling lack of a tail. From then on, I began to know Wolf better, and it went from there. Being in the forest in Finland helped a lot too, because while I was there, I spent some time trying to perceive it as he does. * How far back in the deep past is Torak's world? It's six thousand years ago, which is after the Ice Age, and before farming reached this part of northern Europe. The land is one vast Forest, peopled by small clans of hunter-gatherers. They have no writing, no metals, and no wheel. They don't need them. They're superb survivors. They know every tree and herb in the Forest. They know how to make beautiful, deadly weapons from flint and bone. They know the animals they hunt, and they respect them, because without them they won't survive. PAVER 9 * How did you capture the way of life of the clans? To find out what the clans wear and eat and live in, I've studied archaeology, which has always been a passion of mine. In Torak's world, each clan has its own particular clan-tattoos and clothes; its own weapons and shelters and hunting customs. Torak is going to discover a lot of strange things as he journeys through his world, meeting the different clans. But that's not all. How do the clans think? What do they believe about the Forest, and about hunting and animals and death? For that I've learnt from more recent hunter-gatherers such as Native Americans, Inuit, Sami, the Ainu of Japan, and many African tribes. And again, in Torak's world, each clan has its own ideas about how the world came about, and what happens when you die, and how to avoid demons and sickness. Sometimes these ideas are very different from those of other clans, as Torak is going to find out in later books. * What one piece of advice would you give to aspiring authors? I think the main thing is to keep writing, preferably every day, no matter how busy you are with your job, children, etc. Reading some ‘How to write a novel’ books can help too, as it avoids having to reinvent the wheel. But there's no substitute for keeping writing - despite rejection letters, frequent bouts of ‘I'll never get there in a million years’, and well-meaning friends' suggestions that maybe you should try something else in the interests of sanity. One other thing: I don't think it's a great idea to talk about your work in detail to other people; just get on with it. I've noticed that people who tell me the plot of their novel-in-progress or screenplay or whatever in fascinating and exhaustive detail tend not to be the ones who ever get it finished. * What do you do in your free time? Do you have hobbies? I don't have an awfuland lot of thefree scenery time, isbutsowhen amazing. I'm not I'mwriting, also enjoying I love watching having my films - old, modern, fore own (small) garden for the first time. I currently have eight different kinds of bamboo in it - which is probably about all it can take! PAVER 10 * Are there times when you are so absorbed in your story that you have a hard time relating to the ‘real’ world? I find that's the case most of the time, but it doesn't usually bother me. It occurred to me the other day that, what with writing, watching television, going to the cinema and day-dreaming, I probably only spend a small fraction of every day in the ‘real’ world. Perhaps that's why I enjoy travelling so much: suddenly I'm catapulted into the ‘real’ world for whole days at a time, which makes a refreshing change. * They say writing is a lonely job. Do you find that to be true? Yup, no getting away from it. If you're a writer, you spend virtually all of your time on your own. When the writing's not going well, that can be difficult (but then, isn't that why videos were invented?). But when it's going well, it hardly feels like solitude, because you're with your characters. * What do you do when you feel exhausted and burnt out? Do you sometimes just run away from it all? What I should do is go away somewhere for a short break and a change of scene. What I tend to do is watch back-to-back Star Trek or The Simpsons videos - in other words, something completely different from the sort of thing I write - or put in a long day in the garden. That usually does the trick. * Your favourite writers? I've always loved the Sheridan nineteenth Le Fanu. century And writers I love- Jane Homer, Austen, but IThomas have to Hardy, be careful Anthony Trollope, Dosto about when I read him, because if I approach the Iliad when I'm feeling less than confident, I end up asking myself why I ever bothered to pick up a pen. Well, wouldn't anyone? PAVER 11 * What is your biggest dream? An Oscar for my yet-to-be-thought-of original screenplay would be rather nice. * What is the most rewarding and enjoyable part of being a writer? Two things. First, when (very occasionally) a scene comes alive the first time you put pen to paper. That's what I write for: that rare buzz when it's really going well. The second reason has to do with when I receive a letter from a reader, saying how much my novel meant to her. It's an exhilarating feeling, as well as a privilege, to know that you have moved someone whom you've never met. * What is the scariest experience you’ve ever had? It was a few years ago, in the Sierra Nevada of southern California, and I was hiking alone on a deserted mountain trail. Suddenly, on the opposite side of the stream I was following, a large female black bear and her two cubs appeared out of nowhere. One moment I was in the twentieth century; the next, I was back in the prehistoric forest. An old rancher in Wyoming had warned me that a female bear with cubs is at her most dangerous. He'd also told me that as bears can't see too well, and hate surprises, it's vital to make a noise to let them know you're there: his tip was to sing! The mother bear and her cubs was only thirty feet away from me, on the other side of the stream - but she clearly hadn't spotted me yet; and my way home led right past her. I couldn't hope to creep by unnoticed; I had to tell her I was there. So I took a deep breath and launched into Danny Boy. To my horror, instead of just watching me go, she pricked up her ears and started purposefully across the stream - towards me. That's when the fear really kicked in. If I made a wrong move, she might attack. And I had no defences. All I could do was try to persuade her that I wasn't a threat. I stopped. She stopped in midstream. We looked at each other. She rocked slowly from side to side, as if considering whether to rear up on her hind legs and go for me. For what seemed like a lifetime I side-stepped slowly past her. She watched me all the way. Then, finally, my path dipped out of sight - and I ran like hell. It was the most terrifying and exhilarating experience of my life. It also felt weirdly as if I'd been back in time. In those brief moments when I was facing the PAVER 12 bear, thousands of years of civilisation were suddenly irrelevant; I knew what it was to be prey. I'd been in Torak's world. *** CONTACT Michelle Paver is represented by Peter Cox/Redhammer Redhammer 186 Bickenhall Mansions : London : W1U 6BX : UK Web: www.redhammer.biz Contact Form: http://redhammer.info/client/michelle-paver/#client-section-4 PAVER 13