Tree Management Plan - National Capital Authority

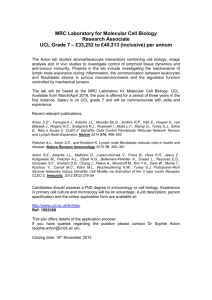

advertisement