Notes submitted by Highlander & Fahey

advertisement

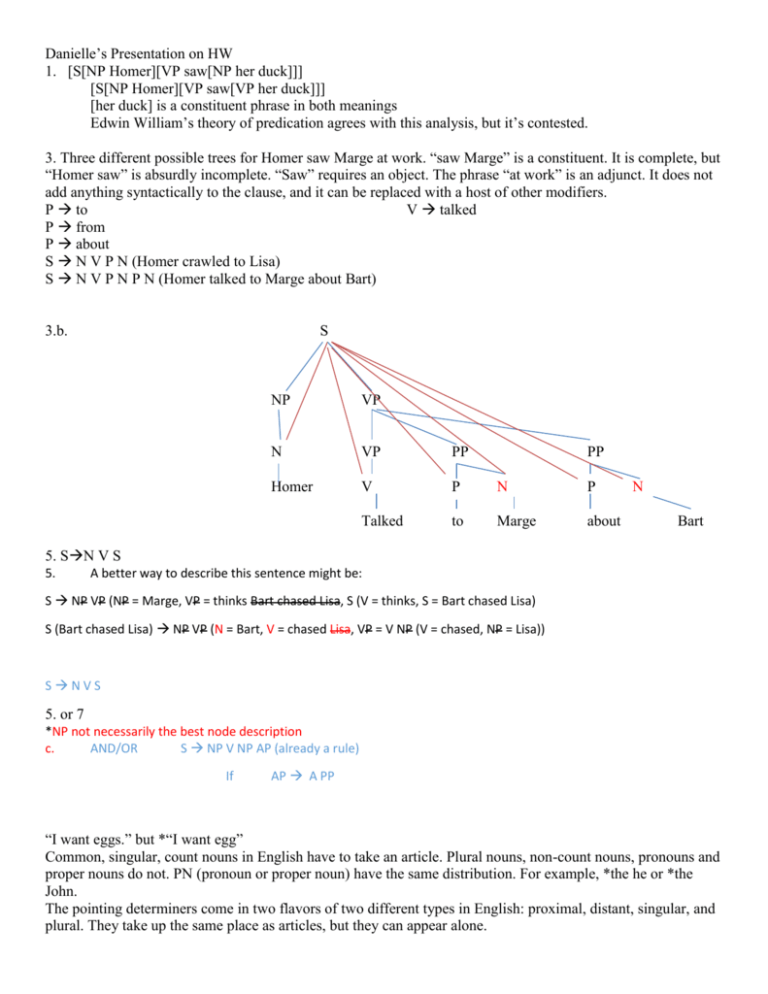

Danielle’s Presentation on HW 1. [S[NP Homer][VP saw[NP her duck]]] [S[NP Homer][VP saw[VP her duck]]] [her duck] is a constituent phrase in both meanings Edwin William’s theory of predication agrees with this analysis, but it’s contested. 3. Three different possible trees for Homer saw Marge at work. “saw Marge” is a constituent. It is complete, but “Homer saw” is absurdly incomplete. “Saw” requires an object. The phrase “at work” is an adjunct. It does not add anything syntactically to the clause, and it can be replaced with a host of other modifiers. P to V talked P from P about S N V P N (Homer crawled to Lisa) S N V P N P N (Homer talked to Marge about Bart) 3.b. S NP VP N VP PP Homer V P N P Talked to Marge about PP N Bart 5. SN V S 5. A better way to describe this sentence might be: S NP VP (NP = Marge, VP = thinks Bart chased Lisa, S (V = thinks, S = Bart chased Lisa) S (Bart chased Lisa) NP VP (N = Bart, V = chased Lisa, VP = V NP (V = chased, NP = Lisa)) SNVS 5. or 7 *NP not necessarily the best node description c. AND/OR S NP V NP AP (already a rule) If AP A PP “I want eggs.” but *“I want egg” Common, singular, count nouns in English have to take an article. Plural nouns, non-count nouns, pronouns and proper nouns do not. PN (pronoun or proper noun) have the same distribution. For example, *the he or *the John. The pointing determiners come in two flavors of two different types in English: proximal, distant, singular, and plural. They take up the same place as articles, but they can appear alone. Larson’s approach is a sandbox approach. Outside knowledge may not be used. NP V NP AP Marge found the vase broken. NP V NP AP Bart left the party angry. “John prepared the fish raw.” vs. “John prepared the fish naked.” What is the difference? In the first one, raw refers to the fish, and in the latter example, naked refers to the subject NP. Therefore, the APs of these two examples connect to different nodes in the syntax trees that represent them. Syntactic v. Semantic ambiguity -Semantic ambiguity seems to require syntactic ambiguity, but not the other way around. However, there are exceptions to this. -“[NPJohn CONJand NPSue CONJand NPLarry] all left” is not ambiguous semantically, but -there are two different possible syntactic analyses. -The two different possible analyses are equal. It’s like comparing (3+2)+1 and 3+ (2+1). NP John and NP Sue and Larry NP NP John and And Larry Sue -“All courses do not have prerequisites” is an example of a semantically ambiguous sentence that is not syntactically ambiguous. “Not” has to be in the VP or PredP. “Courses” has to be in the subject position. The syntax trees are identical for both both possible interpretations. “All students like some teacher” is another example of this. -logical form + abstract theory of covert movement of quantifiers -quantifiers and negation Weakly v. Strongly equivalent theories -The following two trees are strongly equivalent with regard to constituency structure, but they differ in regard to labelling. NP CN Art the AP tall CN man DP NP D the AP tall CN man Pro-= in place of -Proforms Many classes that substitute for many categories. Speaker’s knowledge of language -Speakers know how to form language, but they do not know the mechanics. It is analogous to a snowboarder. They know how to snowboard, but they could not tell you about the physics of it. Ambiguity v. uncertainty -Uncertainty (not explicit) is different from ambiguous (explicitly asserting two different things). -think of verbs Cleft is a subset of dislocation