Patzke_Annotation_Lave

advertisement

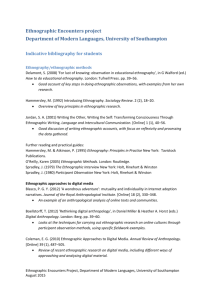

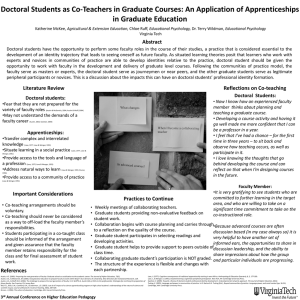

Karin Patzke EcoEd Annotation 4 Lave, Jean, and Etienne Wenger. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral participation. Cambridge university press, 1991. Lave, Jean. Apprenticeship In Critical Ethnographic Practice. University of Chicago Press, 2011. “In our view, learning is not merely situated in practice – as if it were some independently reifiable process that just happened to be located somewhere; learning is an integral part of generative social practice in the lived-in world. … Legitimate peripheral participation is proposed as a descriptor of engagement in social practice that entails learning as an integral constituent” (Lave and Wenger (1991), 35). Legitimate peripheral learning is a conceptual frame for understanding how persons engage in education throughout one’s life. As a frame, it has had many iterations and conceptual names, including apprenticeship and situated learning. However, in this most recent iteration, the focus is on ‘ways of belonging’ as a means by which learning is a social endeavor. Learning is not restricted to one place and participants are not passively receiving information. Instead, locations of learning change as students move to ‘get a better view’ and become more involved in the practice/process at hand. “In contrast with learning as internalization, learning as increasing participation in communities of practice concerns the whole person acting in the world. Conceiving of learning in terms of participation focuses attention on ways in which it is an evolving, continuously renewed set of relations….” (Lave and Wenger (1991), 49-50). Lave and Wenger present learning as a reflexive endeavor linked to bodily motion, time, and location. These considerations highlight the diverse modes of learning in consideration of age and locality. While there is an agenda in teaching, how information is presented – to be learned by students – requires a change in focus from communication/reception to ‘acting in the world.’ Apprenticeship as a conceptual frame implies an active method of learning; participation highlights the reciprocal mode of teaching/learning. ‘Communities of practice’ highlights these modes of belonging to continuously iterative learning systems. Furthermore, the author’s focus on evolving relationships reveals the reflexive attitudes developed to continue learning / continue participation. “One assumption underlying social practice theory (and thus this conception of critical ethnographic research) is that theoretical and empirical endeavors are mutually constitutive and cannot be separated – social practice theory is a theory of relations. So research on learning (through apprenticeship) and research as learning (through critical ethnographic practice) are each and together empirical/theoretical practices” (Lave (2011), 2). This preliminary assumption guides Lave’s narrative in Apprenticeship In Critical Ethnographic Practice. Her discussion of her ethnographic work is not about the results of the observations and interviews, but about the practice of ethnography itself. Lave does not write a cohesive narrative about tailoring practices in Liberia. Instead, she focuses on moments in her field work, which she calls the ‘the process of research.’ This change in viewpoint (from looking at ethnographic subjects to looking at her ethnographic practices) situates Lave’s narrative on her own learning in the field, i.e. her own apprenticeship to critical ethnography. In Situated Learning, Lave draws from her ethnographic work conducted in the 1970s with tailors in the cities of Vai and Gola in Liberia to illustrate the concepts of peripheral participation. Through multiple iterations she moves beyond highlighting the differences in everyday practices of mathematical learning to focus on how the ethnographic study revealed new insights into learning practices generally. In Apprenticeship In Critical Ethnographic Practice, Lave presents a self-reflexive narrative that highlights her own changes – not only in approaching the field, but how she re/presents herself in the field and beyond, i.e. as an apprentice to the practices of critical ethnography. Furthermore, as she identifies as an apprentice herself, ethnography takes on new forms and meanings while hidden theoretical assumptions and constraints are revealed. In identifying what ‘critical’ may mean in critical ethnographic practice, she identifies the desire to “change theoretical practice in the process” (Lave (2011), 10). As in the third quote above, Lave attempts to cohesively link empirical practices and theoretical practices through critical ethnographic inquiry. This backgrounds practices like interviews and (participant) observation and foregrounds the social, ethical, and theoretical implications of acting in the field. Furthermore, as Apprenticeship… demonstrates, it’s not just the ethnography that changes, but the ethnographer who is required to re/evaluate methods applied in the field, the consequences of those methods, and the lenses through which those methods are interpreted as ethnographic observations. Thoroughly self-reflective, Lave calls into question ethnographic practice itself. However, in her criticality, she salvages the practices as a means of learning – not about a so-called ‘other’ nor to highlight ‘difference’ but to draw attention to the ways in which critical ethnographers, at times, can be exposed to new insights in quotidian practices such as learning.