File - Corie Zylstra ePortfolio

advertisement

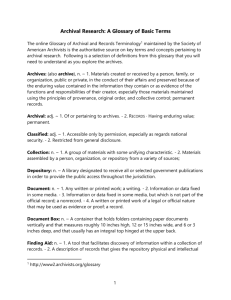

1 CUSTODIAL AND POST-CUSTODIAL APPROACHES TO ARCHIVES Corie Zylstra LIS 775: Introduction to Archival Principles, Practices, and Services Professor A.W. Dunbar April 25, 2012 2 Abstract Little in this world is ever constant; much in life is always changing, and so too are archives, archival theory, and archival practice always changing. The archival area that this theory development paper discusses is that of archival custody and the custodial and postcustodial approaches to archives. Until the late 20th century the idea of archives having physical custody of records was the generally accepted practice. Then electronic records were introduced into the mix and changed everything. This paper will begin with a timeline pointing out the important events in archival custody theory and how custodial approaches have changed over the years. The main portion of the paper will compare the custodial and post-custodial approaches to archives, examining the arguments for and against both and also middle ground options. It will end with an analysis of both approaches and a look at their future in the archival profession. Custodial Timeline Archival theory goes back in time a long way, and although the post-custodial approach seems fairly recent due to electronic records, ideas about it can be traced back over 130 years. In 1874 a man named Theodoor Van Riemsdijk, a friend of Sam Muller (one of the three authors of the Dutch Manual) went to work as the city Archivist in Zwolle. By 1877 Van Riemsdijk had developed firm beliefs about the organization and custody of archives, but more importantly he “focused not on the actual record, but on the record-creating process. He tried to understand why and how records were created and used by their original users, rather than how they might be used in the future.”1 Van Riemsdijk’s interest in records creation over their future use is a precursor of the post-custodial approach in which the understanding of business functions and transactions becomes just as or more important than the details of the documents created by those businesses. 1 Eric Ketelaar, “Archival Theory and the Dutch Manual,” Archivaria 41 (January 1996): 33. 3 These ideas, however, would not develop further until many years later because the postcustodial approach was not seen as necessary, and many archivists did not look on the idea favorably. “The pioneers [like Shellenberg] knew all about noncustody: records lost and damaged, others in vast disarray and a new National Archives to deal with the aftermath. They could not possibly wish that situation on later generations for records in any format.”2 Archivists like Shellenberg felt that custody was important because they would keep the records organized and prevent loss and damage. Unlike the subject of appraisal on which Shellenberg and Jenkinson had differing views, custody was something that they came closer to an agreement on. In 1937 Jenkinson defined archives as 'documents that are set aside for preservation in official custody'. Custody was critical to what he called 'Archive quality', which depended on records appraised as having continuing value as archives being managed by 'an unblemished line of responsible custodians', whose 'primary duties' were the 'physical and moral defense' of the archives in their care.3 Jenkinson obviously felt the same as Shellenberg, that the physical custody and protection of archives was an important and primary task of archivists or custodians. However, in the second half of the 20th century electronic records began to change many of the accepted ideas about archives, especially the ideas of how to deal with the custody of such records. In the 1960’s the Society of American Archivists (SAA) emphasized the importance of educating archivists on how to deal with electronic records. “The emphasis on educating archivists showed a basic assumption: that archivists would and should manage electronic records in an archival setting, i.e., valuable records would be transferred to an archives which 2 Linda J. Henry, “Schellenberg in Cyberspace,” American Archivist 61, no. 2 (1998): 320. Don Boadle, “Reinventing the Archive in a Virtual Environment: Australians and the Non-Custodial Management of Electronic Records,” Australian Academic & Research Libraries 35, no. 3 (September 2004): 242. 3 4 would hold custody of them, preserve them, and make them available for use.”4 Custody was still very important to the SAA. They may not have seen the issues electronic records would present in the future that would make post-custodial management a popular approach. Two decades later the idea that electronic records should remain in the custody of their creators and that archivists should help creators manage their records from their creation immerged. In 1980 F. Gerald Ham introduced the term “postcustodialism into archival vocabulary and theory.”5 He saw the possible future of the custody of archives in the way electronic records would be cared for and the role of the archivist. “Ham foresaw that ‘managing’ rather than merely ‘keeping’ records would become the role for the archivist of the future.”6 The post-custodial approach to archives would mean archivists would have more management of records before and as they are being created instead of having just the role of custodian. The approach then would encourage the action of leaving those records with the creator. During the 1980’s many archivists did not know which approach to use, the old or the new7, and ever since that time, great debate has developed between many prominent archivists and historians over which approach, custodial or non-custodial, is better. 4 Henry, “Schellenberg in Cyberspace,” 312. 5 Jeannette Allis Bastian, “A Question of Custody: The Colonial Archives of the United States Virgin Islands,” American Archivist 64, no.1 (Spring/Summer 2001): 97. 6 Ibid. 7 Henry, “Schellenberg in Cyberspace,” 312-13. 5 Bearman and Cook Versus Eastwood American David Bearman was the most outspoken critic of custody8 and one of the biggest supporters of the post-custodial approach even though he was not an archivist.9 Bearman and archivist Terry Cook shared their views on the role of the archivist in that the role of custodian should be abandoned. “The role of the archivist would be to work together with the records manager in identifying the records that are significant both for ‘institutional corporate memory’ and the broader documentation of society.”10 The idea was that archivists would give up the custody of electronic records and instead work closely with records managers to appraise the records based on the relevance to the corporation as a whole and then on its relevance to the society in which it was created, not on at all based on the record itself. This close relationship that archivists have with creators and managers in the postcustodial approach might be cause for appropriate concern. In working closely with records managers archivists may certainly have a better understanding of the importance of the records to the business and society instead of appraising the records individually; however, this close relationship may also increase the archivist’s subjectivity in appraising the records.11 The biases of records creators and managers may skew or influence the archivist’s own appraisal, an issue that would be less likely to occur if the archivist had taken custody of the records without any input from the creators and managers. Archivist Terry Eastwood also saw the danger in the post-custodial approach and advocated that custody of records remain with archivists. “The physical custody of archival 8 Boadle, “Reinventing the Archive in a Virtual Environment,” 243. 9 Henry, “Schellenberg in Cyberspace,” 323. Reto Tschan, “A Comparison of Jenkinson and Schellenberg on Appraisal,” American Archivist 65 (Fall/Winter 2002): 193-94. 10 11 Ibid., 194. 6 material remains essential for guaranteeing an uncorrupted and intelligible record of the past, and in terms of ensuring accountability for both institutions and for society as a whole.”12 Eastwood saw the danger of subjectivity and bias and the corruption of records that they could cause. Archival custody is important for making sure companies remain accountable to themselves and to society whether the biased appraisal of records becomes intentional or unintentional. The “New Paradigm” A slightly different take on the post-custodial approach is known as the “new paradigm.” The major difference is that not only do archivists aid managers and creators in appraisal but they also take part in the creation of the records. Proponents of the new paradigm “argued that archivists should change their focus, from the content of a record to its context; from the record itself to the function of the record; from an archival role in custodial preservation and access to a nonarchival role of intervening in the records creation process and managing the behavior of creators.”13 It seems that if archivists can have their say in the creation of the records and therefore their content, then during appraisal focus can be taken away from the record content and placed on context and function. Strong advocates of the new paradigm have little good to say about the traditional custodial approach. “New paradigm supporters urge archivists to ‘cease being identified as custodians of records’ because, among other things, this role ‘is not professional.’ An archives with custody is ‘an indefensible bastion and a liability.’ These writers maintain that creators of records or other institutions, whether they are archives or not, can take care of archival 12 Ibid. 13 Henry, “Schellenberg in Cyberspace,” 313. 7 records.”14 There is certainly a strong impression that these new paradigm supporters have a very low opinion of traditional archivists and feel that they are no longer necessary. Archivists seem to be necessary only if they are working with the records creators and do not attempt to take physical control of the records. Linda J. Henry, author of “Shellenberg in Cyberspace” points out that “in general, supporters of a new paradigm seldom referenced past archival literature or practice”15 to defend or explain their new approach. They did poor research and defended their positions by referencing others who held the same views. They also, like Bearman, lacked experience in the archival field. Henry uses Shellenberg as a good example of how to develop new ideas. He “developed his concepts in the context of both archival history and his own and others' experiences. In contrast, supporters of the new paradigm for electronic records seldom ground their pronouncements in, or demonstrate an understanding of, Schellenberg or any historical archival theoretician.”16 The reliability of these supporters and the new paradigm are called into question by their lack of research and unwillingness to look beyond their own opinions and experiences. Henry suggests that for a good example supporters of the new paradigm should look at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) which has almost 30 years of experience working with electronic records. “Supporters of new approaches to electronic records have not tried to learn what NARA does or what it has learned about electronic records from its custodial experience.”17 If advocates for the new paradigm used the NARA as an 14 Ibid., 319. 15 Ibid., 313. 16 Ibid., 322. 17 Ibid., 323. 8 example they might improve their approach and have a better understanding of and regard for the traditional custodial approach. Instead, they feel that traditional archival practices cannot handle new technologies, and therefore must be changed to accommodate them. Post-custodial Management in Australia It may well be advisable to work closely with the creator of the records to ensure that electronic archives are stored, documented and managed in appropriate formats, well before they are transferred to an institutional repository. Archivists and manuscript librarians have traditionally been wary of this kind of early intervention in the life-cycle of personal archives. But this approach is integral to the “post-custodial” and “records continuum” thinking which now underpins much of the work in the government records sector in Australia.18 One area of the world in which the post-custodial approach, also known as the distributed management approach, took off earliest was Australia where they believed that post-custodial management of electronic records “was consistent with Australian practice and compatible with Australian contributions to archival theory.”19 Post-custodial management in Australia is very similar to what has already been described, but includes even more involvement in the creation of not only the records themselves, but also the systems and technology used to create and store the records. Archivists “work collaboratively with other information specialists, including records managers and information technology professionals, to analyze information management requirements, design appropriate systems, and estimate and oversee the management of risks involved in keeping or destroying information.”20 Essentially, archivists became record keepers who managed records throughout their entire life cycle. 18 Toby Burrows, “Personal Electronic Archives: Collecting the Digital Me,” OCLC Systems & Services 22, no. 2 (2006): 86. 19 Boadle, “Reinventing the Archive in a Virtual Environment,” 242. 20 Ibid., 243. 9 The National Archives of Australia (NAA) thought that post-custodial management was the best practice for dealing with electronic records. They believed that in order to ensure that electronic records would receive proper maintenance and still be accessible they must be kept with their creating or controlling agency. That agency would then have to operate “in compliance with standards established by the National Archives.”21 Archivists and the records agencies worked closely together under the same rules to ensure the best protection and use of electronic records. It seems that under this form of post-custodial management there is more of a joint custody of records because of how close the two sides work together. Archivists still have custody of the electronic records because they have access to them. They simply lack the physical possession in their own repository. Two prominent Australian archivists that jumped on board with post-custodial management were Glenda Acland and Sue McKemmish. Acland, the archivist at the University of Queenland, worked to establish “an integrated record keeping operation that combined the university's records management and archival functions in a single organizational unit under her control.”22 Her goal follows the same form that was laid out by the NAA; have the archivist and the agency work together, and in this case under Acland’s control. McKemmish, Monash University’s archivist, saw an entirely new future for the archival profession in which archivists would no longer have custody of physical objects but would be concerned “with issues of 'moral defense': that is, the elucidation of conceptual relationships between creating structures, animating functions, and the resulting (virtual) records.”23 Archivists would clarify the relationships between the agencies, the ways those agencies created 21 Ibid., 243. 22 Ibid., 244. 23 Ibid. 10 their records, and the records themselves. The focus would again be on the life cycle of the record beginning from even before they were created. In regards to the actual custody of the electronic records McKemmish also believed that they should remain with the creating or controlling agency. There were also archivists who opposed Australia’s post-custodial management including Eastwood and Luciana Duranti. Three concerns that Eastwood voiced were that first, smaller or “weak” institutions would not be able to compete in a post-custodial environment. They would not be able to afford the costs of preserving new electronic formats, nor would they be able to begin post-custodial management because the larger archives had more money to do so; therefore, the smaller institutions would have little chance at survival. Eastwood’s second concern was with separating electronic records from records in other formats. “To leave digital records in the hands of creating or controlling agencies, was itself 'unprofessional' because it complicated (and possibly vitiated) attempts to establish relationships between records in different formats and thereby compromised the archivist's moral defense of the records in his care.”24 If electronic records are kept in different places as records in other formats then their relationships cannot be established which makes it difficult for archivists to justify the records that they do have custodial control over. Eastwood’s third concern was again that of subjectivity and bias of the creator or controller. He emphasized the importance of archival custody to preserve “an adequate and authentic memory of affairs for both primary and secondary users,”25 something that might be questionable if records are left in the care of the creator. 24 Ibid., 246. 25 Ibid., 247. 11 Duranti, a former archivist at the State Archives of Rome, felt very strongly about the issue of subjectivity and bias. Her argument was based on Roman history. “An archive for Romans was a secure place under public control where records were deposited, so that they remained uncorrupted, provided trustworthy evidence, and served as the continuing memory of that to which they attested.”26 It is possible that records can stay with their creators and remain authentic and reliable, but then there is no guarantee, and it is more difficult to keep the creators accountable for the care and appraisal of their records. Duranti also believed in the concept of archival “threshold,” the journey across of which is one way, making post-custodial management impossible. At the threshold the archivist determines the provenance, relates the records to others already in custody, and secures the records in a repository. Director of NAA’s System Integration Project and historian Stephen Ellis did not completely agree with Duranti because there was “evidence to suggest that transfer to archival custody did not automatically guarantee the authenticity of what was being transferred.”27 However, Ellis did agree that finding a way to keep electronic records authentic meant managing the records both physically and intellectually. Other Arguments in Custody Theory In “The Post-custodial/Pro-custodial Argument from a Records Management Perspective” author Alistair G. Tough summarizes the views of Greg O’Shea, Frank Upward, Alf Erlandsson, Heather MacNeil, and Sarah Flynn. O’Shea holds with post-custodial management and believes if archivists wait around for electronic records to become non-current before they work to preserve them then archivists will not find those records; they will be gone. Also on the post-custodial side, Upward begins to question the future of archiving processes “when the 26 Ibid. 27 Ibid. 12 location of the material matters less than its accessibility, when records no longer have to move across clear boundaries in space or time to be seen as part of an archives.”28 It is a compelling argument; why would archives need to have physical custody of electronic records when there is no way to say who exactly has custody. Since the records can be made accessible to everyone, everyone has some amount of intellectual custody and can create physical custody by changing the format. Alf Erlandsson, author of “Electronic Records Management: A Literature Review,” takes a middle ground approach to the custody debate. He connects the custodial issue to the “debate regarding metadata systems strategy. Erlandsson identifies a ‘metadata systems approach’ school who argue that ‘archival descriptive elements should be included in the design of metadata systems’.”29 The idea is to have the archival users in mind when the systems are designed and the records are created. Creating the metadata for electronic records before and as they are being created will aid the archivists later if they are asked to take physical custody. This would eliminate problems archivists had in the past when they received digital records but had no way of knowing the meaning of the records or their connection to their creating body. This middle ground approach to the custodial debate did not appease all custodialists. Many were worried, not about the influence records creators would have on electronic records, but about the systems and metadata creators. “Heather MacNeil and other opponents of this view argue that the evidential value of the metadata may be undermined if it is the product of interference from outsiders rather than a reflection of the needs and concerns of the people who 28 Alistair G. Tough, “The Post-custodial/Pro-custodial Argument from a Records Management Perspective,” Journal of the Society of Archivists 25, no. 1 (2004): 20. 29 Ibid. 13 create and maintain the system.”30 It is possible too that the “outsiders” refers not just to the systems and metadata creators but also archivists who are asked to be involved early on in the records creation as opposed to just being custodians after the records are created. Anyone involved in the metadata creation can change the evidential value. Another important argument is made against the post-custodial approach by Sarah Flynn. She points out that post-custodial supporters view their approach as permanent, but they need to consider that it is merely a transitional phase until a better approach appears. With all the recent and continuous changes in technology and archival theory it is dangerous to take what you have now for granted; it might be gone tomorrow. More Middle Ground Approaches Another option, instead of vying completely for custodial or post-custodial, is to take the middle ground approach like Erlandsson did, choosing neither side or a little of both sides. Ellis asserts that the best choice is to not take an extreme position. He believes that the NAA’s position on electronic records is case sensitive and archivists should not “pin their faith on standards to secure the long-term preservation of electronic records.”31 The post-custodial approach will not work for all records or all institutions, and “the setting and culture of organizations does also have a legitimate role in determining whether post-custodial arrangements will suit them.”32 The type of technology the organization has, the types of records, and even the ways they have approached such issues in the past will help determine if custodial or post-custodial management is best. 30 Ibid. 31 Boadle, “Reinventing the Archive in a Virtual Environment,” 248. 32 Tough, “The Post-custodial/Pro-custodial Argument,” 23. 14 Archives should also remember that they have a choice. In 1996 the American Research Libraries Group's Task Force on Archiving Digital Information had the opinion that records creators had the initial responsibility of archiving their own digital information, but agencies without that ability could partner or subcontract to a “certified digital archives.” These certified digital archives would then also have the ability and responsibility to rescue records at risk of destruction for the public interest.33 Change in Australia Somewhat surprisingly, in 2000 the NAA abandoned the post-custodial model which they had so vigorously promoted and took on “custodial management of ‘digital records of archival (that is, long-term) value’.”34 They realized that they needed to focus on saving records once they were created and they did so primarily by preserving records in XML-based archival data formats. Change, however, comes slowly and not always clearly. In 2002 the Australian Public Service Commission's State of the Service Report “ ‘revealed a lack of understanding and a high degree of confusion among employees regarding their responsibilities and abilities to manage electronic records’ as well as considerable confusion among agency recordkeepers about the requirements of the standard on electronic recordkeeping.”35 Clearly if Australia ever thought they had the custodial issue figured out, then they were wrong. Too many changes to their national standards and the strong debate between custodialists and post-custodialists have left archivists and records creators confused about their responsibilities and which approach is best to take. 33 Boadle, “Reinventing the Archive in a Virtual Environment,” 248. 34 Ibid., 249. 35 Ibid., 251. 15 Final Analysis and Conclusion Major debate over custody is certainly not long in comparison to the history of archives, but it is interesting to me that throughout the history of archives certain opinions on custody have alluded to the issue before electronic records even existed. Over 130 years ago Van Riemsdijk’s focus on records creation rather than the records themselves was an early reference to one part of the post-custodial approach. Later, Shellenberg’s distaste of the idea of not having physical custody of records alluded to the other part of the post-custodial approach, that of leaving custody with the creator. The foresight of these men is incredible because they could not know exactly what the future would bring (the technology and electronic records) but they were aware that the future would bring change and possibly question current archival practice. This foresight is something that many archivists during the height of the custodial debate and even archivists today seem to lack. Archivists on both sides focus too much on the right now and do not take the time to look at the past or think about the future. “The principal proponents in the post-custodial/pro-custodial debate have addressed in quite different ways the charge that some archivists are seeking to colonize the domain of records management. There is, however, one common factor—both sides have asserted the overwhelming intellectual superiority of their own view.”36 It is true that post-custodial proponents such as Bearman need to act and think more like the archival pioneers, taking into consideration what has worked in the past and the experience of seasoned professionals. On the other hand, supporters of custody need to think about the future electronic records and new ways of saving these records in a fast changing world of technology. 36 Tough, “The Post-custodial/Pro-custodial Argument,” 22. 16 In this debate one of the major issues—that of the influence of creators and archivists in the creation of the records—needs to be dealt with. “Archivists are warned that, if they do not involve themselves in the records creation process for electronic systems, they run the risk that these systems will not provide adequate and authentic records to serve long-term institutional and societal purposes. Involvement in records scheduling can mitigate against future problems.”37 This is argued by post-custodial proponents who worry that if archivists do not get involved in records creation then those records will not be adequate enough for future use. It is possible for archivist to be involved early to help organize records in more meaningful and useful ways and to do so without inserting their own subjectivity. However, just because archivists assist in the creation of electronic records does not mean they are better prepared for the ways electronic systems will change in the future, and their current knowledge of electronic systems may be little to no more than the creators’ themselves. It is interesting that post-custodialists think archivists need to be involved in records creation to “provide adequate and authentic records” whereas custodialists believe the opposite. Would not an archivist’s involvement in records creation—involving their own biases and subjectivity—contribute to inadequate or skewed records? When records creators hand all their records over to an archivist to sort through, then the creators do not get involved in the selection and weeding process. On the other hand, perhaps archivists’ involvement will force records creators into being less biased in their selection because they know they are being watched, and at the same time archivists get the metadata and provenance about the records that they might not have gotten if they were not involved. 37 Susan E. Davis, “Electronic Records Planning in ‘Collecting’ Repositories,” The American Archivist 71 (Spring/Summer 2008): 169. 17 If organizations and archives are going to use post-custodial management they will need to find ways to keep themselves accountable. They should create policies and standards that keep records creation and selection in check. These will also help make clear what the duties and responsibilities are of all the people involved. Good work cannot get done if, like the Australians in 2002, archivists are confused about their role. Policies will help keep both creators and archivists accountable to themselves, each other, and future primary and secondary users of the records. One point that everyone needs to accept is that post-custodial management is not beneficial or plausible for all archivists or institutions. Archives that deal with older materials or non-electronic records most likely do not need to or cannot work directly with the records creator, and the records will receive the best care in the custody of the archive. Also, smaller institutions, the “weak” ones that Eastwood was worried about, cannot afford to take on postcustodial management by themselves, and no archive should be forced into any type of management that is not suitable for them. Higher bodies like the NAA should research different theories before changing national standards. Had they done so before implementing postcustodial management they may have found Erlandsson’s metadata systems to be less confusing for archivists, or they could have created clearer policies on post-custodial management. It appears that the post-custodial theory of archives, although it may work in some institutions, is not the best theory. It changes too many defining aspects of archives and makes them into something completely different. A major issue is that it makes the archivist too much involved with the creation of records. A current definition of an archivist is “an individual responsible for appraising, acquiring, arranging, describing, preserving, and providing access to records of enduring value, according to the principles of provenance, original order, and 18 collective control to protect the materials’ authenticity and context.”38 There is no mention of creation. When archivists are no longer just caring for a record but actually contributing to its creation, then they have really gone beyond the role of an archivist. Although it is difficult with today’s electronic records, there must be a better way to collect and save these records without having archivists affect or change their authenticity. If a better way cannot be found, then records creators and archivists need to have clear boundaries and policies for the work they are doing to maintain the accountability, authenticity, and context of the records. 38 “A Glossary of Archival and Records Terminology,” The Society of American Archivists, accessed April 10, 2012, http://www.archivists.org/glossary/index.asp. 19 Bibliography “A Glossary of Archival and Records Terminology.” The Society of American Archivists. Accessed April 10, 2012. http://www.archivists.org/glossary/index.asp. Bastian, Jeannette Allis. “A Question of Custody: The Colonial Archives of the United States Virgin Islands.” American Archivist 64, no.1 (Spring/Summer 2001): 96–114. Boadle, Don. “Reinventing the Archive in a Virtual Environment: Australians and the NonCustodial Management of Electronic Records.” Australian Academic & Research Libraries 35, no. 3 (September 2004): 242-252. Burrows, Toby. “Personal Electronic Archives: Collecting the Digital Me.” OCLC Systems & Services 22, no. 2 (2006): 85 - 88 Davis, Susan E. “Electronic Records Planning in ‘Collecting’ Repositories.” The American Archivist 71 (Spring/Summer 2008): 167 - 189. Henry, Linda J. “Schellenberg in Cyberspace.” American Archivist 61, no. 2 (1998): 309–327. Ketelaar, Eric. “Archival Theory and the Dutch Manual.” Archivaria 41 (January 1996): 31 - 40 Tough, Alistair G. “The Post-custodial/Pro-custodial Argument from a Records Management Perspective.” Journal of the Society of Archivists 25, no. 1 (2004): 19 - 26. Tschan, Reto. “A Comparison of Jenkinson and Schellenberg on Appraisal.” American Archivist 65 (Fall/Winter 2002): 176 - 195.