sand folded

advertisement

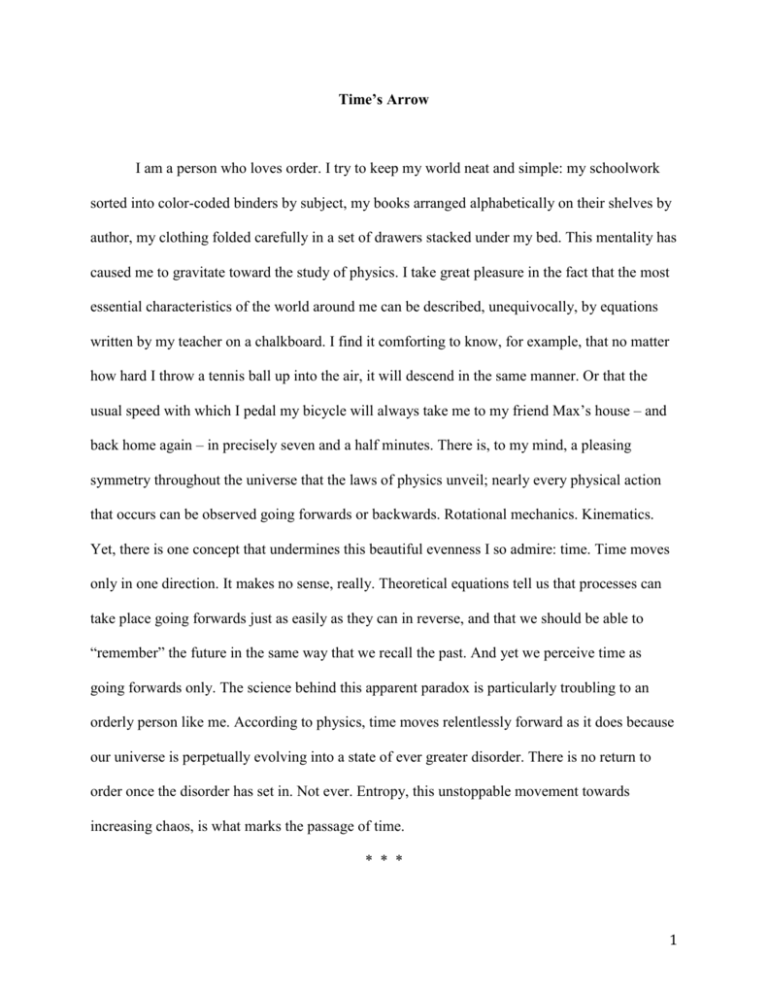

Time’s Arrow I am a person who loves order. I try to keep my world neat and simple: my schoolwork sorted into color-coded binders by subject, my books arranged alphabetically on their shelves by author, my clothing folded carefully in a set of drawers stacked under my bed. This mentality has caused me to gravitate toward the study of physics. I take great pleasure in the fact that the most essential characteristics of the world around me can be described, unequivocally, by equations written by my teacher on a chalkboard. I find it comforting to know, for example, that no matter how hard I throw a tennis ball up into the air, it will descend in the same manner. Or that the usual speed with which I pedal my bicycle will always take me to my friend Max’s house – and back home again – in precisely seven and a half minutes. There is, to my mind, a pleasing symmetry throughout the universe that the laws of physics unveil; nearly every physical action that occurs can be observed going forwards or backwards. Rotational mechanics. Kinematics. Yet, there is one concept that undermines this beautiful evenness I so admire: time. Time moves only in one direction. It makes no sense, really. Theoretical equations tell us that processes can take place going forwards just as easily as they can in reverse, and that we should be able to “remember” the future in the same way that we recall the past. And yet we perceive time as going forwards only. The science behind this apparent paradox is particularly troubling to an orderly person like me. According to physics, time moves relentlessly forward as it does because our universe is perpetually evolving into a state of ever greater disorder. There is no return to order once the disorder has set in. Not ever. Entropy, this unstoppable movement towards increasing chaos, is what marks the passage of time. * * * 1 When I was younger, every summer my mother, father, sister and I would visit my grandparents at their beach house. My grandfather was a large and imposing man in those days, with a loud voice and quick temper. During our time at the beach, my sister and I lived in constant fear of his anger. We spent the days at a small surf club near the house, where multiple generations of families gathered to enjoy the ocean. My grandfather was an important figure in the club. I remember watching as men and women of all ages approached to pay their respects to him while he held court in his chaise by Cabana #10. Children were prodded by anxious mothers to shake his hand. Young men solicited his business advice. Older men posed questions to him about real estate, politics and old movies. After the parade of greetings and requests, my grandfather’s routine demanded a large serving of rum raisin ice cream that the club restaurant stocked especially for him. He ate his treat in his chaise, the dish balanced precariously on his huge stomach. Then he took a nap, and my mother would whisk my sister and me down to the ocean, so that we wouldn’t disturb my grandfather’s sleep. My own routine dictated that the first day at the beach, I stake out an area of untouched sand, far from the body surfers and boogie boarders, the sunbathers and the teenagers with their flat wooden skim boards that skated across the film of water left behind by the receding surf. Settled in my spot, I methodically constructed a wall between the ocean and me. I made sure the barrier was perfectly straight, of uniform height and width. Then I would draw my name on the side of the wall protected from the waves, large capital letters in the sand: LEO. Each successive day, I would squat down and look at how the ocean had climbed the shoreline to eat away at the wall I had created. First the square edges of the divider would soften. After several days its form would gradually loosen into a rounded mound, then just a faint bump in the sand. Finally, the ocean would destroy my barrier completely, sweep up the beach and begin to erase my name. It 2 was then that I knew our vacation was nearly over. When my name had dissolved completely, it was time to go home. * * * Three years ago, my grandfather had a stroke, and he hasn’t been the same since. We visit him regularly, and I have watched as he has gradually declined. He is no longer the powerful, imposing man he once was. After the stroke he could still walk very slowly, with an unsteady, shuffling gait; then after some months he needed to lean on a walker for support; then he stopped walking entirely and had to rely on a wheelchair. Now most days when we visit, he is lying in his bed. The doctors tell us he will never stand up again. On good days, when he is awake and lucid, he is bewilderingly gentle. As a child, I wanted more than anything for him to be nice to me. When he yelled, my sister and I would scramble to escape the room. And yet his benign demeanor now – his sweet and quiet smile – feels oddly inappropriate. I find myself missing the way he once ordered us around, yelled for us to be quiet, scolded us in his booming voice for disrupting his peace with our games and chatter. Now his voice is so faint we can hardly hear him speak. On bad days, he doesn’t remember who I am at all. This past summer, we still managed to visit my grandparents at the beach. With the help of a wheelchair and nurses, my grandfather was able to make it to the beach club and lie on his chaise for few hours each day, but he received hardly any visitors. Many of the men and women who had once come to see him have died. Others, perhaps out of respect for his ailing health, kept their distance. Those who did pull up a chair at Cabana #10 most often found him asleep – his daily nap having now taken over most of his afternoon. Even the ritual of his rum raisin ice 3 cream had ended – the restaurant no longer keeps the unusual flavor in stock, now that my grandfather is unable to eat it. Swallowing is difficult for him. * * * As much as I love order, I seem incapable of keeping it in my life. Every day I’m bombarded with commitments, pulled in a hundred different directions by the demands of my schoolwork, my friends, my sports team. It seems that each successive year brings a new host of responsibilities and obligations to daily life that, despite my best efforts, renders my world increasingly disorderly. It’s my own personal entropy I’m sensing, as inescapable as the laws of physics. While I know that this chaotic tangle of experience is the nature of life, there are moments when I find myself wishing that time’s arrow could, just once, point in reverse. For a brief spell, I could live again like the young child I once was. My homework and social obligations disappear. The pressures of adolescence abate. The ticking of the clock constitutes nothing more than a rhythmic background noise, not the counting off of tasks still remaining to be completed. And my grandfather would stand again. A towering figure of authority in front of the blue and white wooden frame of Cabana #10, he would maybe yell at my sister and me to get lost so that he could relax on his chaise without being disturbed after a morning of consultations. I would race to the beach, where my name, LEO, would be written forever on the shoreline, protected by a wall of sand miraculously restored to perfect uniformity by the ocean waves, never to be erased from view. 4

![PERSONAL COMPUTERS CMPE 3 [Class # 20524]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005319327_1-bc28b45eaf5c481cf19c91f412881c12-300x300.png)