Report No. 78/15 - Organization of American States

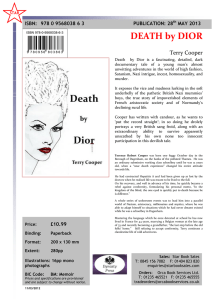

advertisement