Gift K - Kansas State University

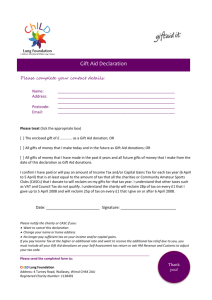

advertisement