The stepchild of labour law

The stepchild of labour law

The complex relationship between independent labour and social insurance

Inaugural lecture

delivered upon appointment to the chair of Professor of Social Insurance Law at the University of

Amsterdam on 2 December 2011

by

Mies Westerveld

This is inaugural lecture 423, published in this series by the University of Amsterdam.

Lay-out: JAPES, Amsterdam

© University of Amsterdam, 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in an automated data file, or

made public, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or

otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Inasmuch as the production of copies of this publication is permitted under Article 16B of the Copyright

Act 1912 in conjunction with the Decision of 20 June 1974, St.b. 351, as amended by the Decree of 23

August 1985, St.b. 471 and Article 17 of the Copyright Act 1912, the legally required payments must be

made to Stichting Reprorecht (PO Box 882, 1180 AW Amstelveen, The Netherlands). Any requests

regarding the inclusion of any part or parts of this publication in anthologies, readers and other

compilations (Article 16 of the Copyright Act 1912) should be directed to the publisher.

Madam Rector,

Honoured guests,

Carla Cantenaar was 35 years old and working in the healthcare sector when she developed cancer.

After three years and many rounds of chemotherapy, she was pronounced cured. Nevertheless, the

damage caused by the disease and aggressive medication had left her with only a limited capacity to

work. She had no hope of returning to her previous work. Under the Disability Insurance Act (WAO), the

law that was in force at the time that this story took place, she was still considered an 80-100 case, to

use the applicable jargon. Carla decided not to give up and instead to apply all her strength to find out

what was still possible for her. She soon learned that few employers are eager to hire an employee with

a history of illness and real constraints of the kind she had. She talked with her employment

specialist about the possibility of starting a small business, in which she would coach people like herself

as they try to return to a normal life. The employment specialist was amenable to the idea. Carla was

able to start within the framework of the Disability Insurance Act, with the requirement to report back

in a year about how she had fared. Carla applied all of her energy to her company. One year later, she

was able to announce with pride that she had actually realised a profit. Her joy was short-lived,

however, when she heard that she would have to repay almost twice as much as she had earned to the

Employee Insurance Agency (UWV). To ease the pain, she was informed that it was possible to work

out payment arrangements, of course.

Bertus Vuijk was 48 years old. He was drawing unemployment benefits (WW) after having been

declared redundant. Even though he had not read the report by the Bakker Commission, Bertus knew

that his chances of returning to permanent employment were low.1 He approached the Employee

Insurance Agency to ask whether he could start his own company while receiving unemployment

benefits. He already had a name: “Bertus Consultancy, for all your business transitions”. Bertus had

worked for years in a large company. From his experience, he knew that employers often use private

consultants to supply expertise that their own employees do not possess. Bertus received a green light

as well, and he was able to keep his benefits temporarily, even though he did not face any physical

restrictions (as had been the case with Carla). He was required to report the number of hours he

worked each month. In his case, the balance was calculated and settled each month, in order to

prevent the debt from building up. After one year Bertus, too, received the fright of his life: the

Employee Insurance Agency (UWV) had compared his timesheets to the hours that he had reported to

the tax authorities in order to claim the self-employment deduction and found that they did not match

up. Although Bertus was aware of this, he had assumed that this would not be a problem, as the

reports involved two different aspects of running a business. The UWV took a harder approach with

Bertus. Because he had submitted false information, he would be required to repay the excess benefits

he had received, in addition to facing a hefty fine and perhaps even criminal prosecution.

The nice thing about this chair, ladies and gentlemen, is that hardly any imagination is required to come

up with interesting examples. The practice is always more colourful than you could possibly imagine

behind your desk. I have selected these two cases as an opening for this public lecture about the

relationship between my field, social insurance, and self-employment. This relationship has always

been complicated, and it is complicated still. I would like to illustrate this with some examples from

recent history, as well as from the here and now. These cases will show that social insurance has never

really known what to do with the phenomenon of self-employment. I also hope that these cases will

make clear that is time for this topic to be put back on the agenda.

The rise of the freelancers

Long ago, when the first social insurance was being designed, there was already a category of “nonworkers”: people who are quite similar to employees in terms of economic position but who are not

employees, as they do not work for an employer. At that time, this category referred primarily to

farmers, gardeners and small shopkeepers. Just like employees, they often worked long hours without

earning enough money to set aside a reserve for later. In the wake of the discussion on the Disability Act

(IW), this raised the issue whether some type of social insurance should be arranged for this group. This

took the form of the Old Age Pension Act, which came into force parallel to the Disability Act. In

contrast to the IW, the Old Age Pension Act was not a form of social insurance; the law provided access

to affordable old-age facilities on a voluntary basis. Very little use was ever made of this possibility.

Bosschenbroek and van den Berg attribute this to the fact that, because the government had already

extended free pensions twice in the past, those to whom the Act applied reasoned that this would also

be the case when their time came.2 This assumption resembles the grasshopper analogy recently

drawn by VARA Ombudsman Pieter Hilhorst. “Freelancers, including myself, are grasshoppers. They

prefer not to think about the winter. They often have scanty retirement funds and, in many cases, they

have made no provisions for the event that they should become unable to work due to illness. Or

perhaps they do think about the winter, but are unable to prepare themselves for it”.3 With this allusion

to the fable by De la Fontaine, we return to the present.

In recent decades, the phenomenon of small independent businesses has soared, not only in our

country, but in many Western welfare states. In 2007, Buschhoff and Schmidt identified the rebirth of

entrepreneurship as one of the most significant developments in contemporary European labour

markets. In this context, they referred to the rise of what they call the “new self-employed”.4 The

designation “new” should be considered relative, though. The term freelancer is derived from the “free

lances” of the Middle Ages – entrepreneurs who, before the term was coined, hired themselves out,

complete with horse and lance, to the lord who made the highest offer.5 The rise of the “new” small

businesses raises questions to which the existing employment arrangements do not always have a

good answer. The classic 1999 report by Supiot and colleagues refers to an expanding “grey area” of

workers who are neither clearly employed nor clearly independent.6 This category lacks the certainty

and stability of work that employees enjoy in exchange for their subordination to employing

organisations and their rules. Self-employed people make a trade-off in which they forego security in

favour of the opportunity to make profits supported by fiscal facilities.7 For those falling into the

category described by van der Heijden – “economically comparable with employees but with no legal

status” – neither condition applies.8 These workers fall through the cracks with regard to both

protective labour laws and opportunity-creating business laws. On the other hand, self-employed

people are not always victims of a business world that exchanges permanent staff for less-expensive

non-employees. The category of freelancers also includes well-qualified workers who prefer the

freedom of entrepreneurship to the subordination required by labour laws and the weak risks

associated with the solidarity generated by social insurance. Supiot and colleagues establish that the

labour supplied by freelancers has increased the quality of work in some situations, while lowering it in

others. A quality-enhancing effect occurs when the deployment of self-employed people allows more

space for the abilities of truly autonomous workers (most of whom are highly qualified), thus leading

to innovation in the employing organisation. The opposite occurs when self-employment is used to

divest workers at the bottom of the labour market of the protections that are provided by labour law.9

The report by Supiot and colleagues dates from the late 20th century. Ten years later, Houweling

establishes that labour law still does both too much and too little for the self-employed and that this

situation emphasises the need for a fundamental debate about the positioning of freelancers and the

future of labour law.10

Self-employment in the Netherlands: definition and figures

The advent of the “new” independent enterprise has also raised difficult questions with regard to

social insurance. Before I address this issue, allow me to frame the discussion with a few figures. In

2006, self-employed people accounted for approximately 15% of the total workforce in the 25 EU

Member States. Freelancers comprised two-thirds of this group (approximately 20 million). Although

most were active in the agricultural and retail sectors, sub-contracting and contracting out brought

increasing numbers of freelancers into the construction and personal services sectors. These numbers

were obtained from the 2006 Green Paper on Labour Law.11 I shall refer to this European Commission

document again later in my address.

To some extent, we can only speculate as to how the Commission arrived at its assessment. As

observed by Aerts, freelancers do not lend themselves well to description, and they are difficult to trace

as a group. The concept does not exist in any legal sense, and its meaning is ambiguous even outside

the legal context. In an attempt to parse the notion, Houweling identifies the “classic” and “new” selfemployed, further distinguishing between “hybrid”, “true” and “involuntary” self-employed people.12

This sub-categorisation is problematic, as the concepts are neither mutually exclusive nor static.

The lack of clarity surrounding the designation of self-employment can explain why the 2007 estimates

concerning the number of freelancers in the Netherlands ranged from 150 to more than 500

thousand.13 Following a 2010 recommendation of the Social and Economic Council of the Netherlands

(SER), an unambiguous definition is now being applied. Based on this definition, the number of

freelancers exceeded 675 thousand in 2007, and it had increased to approximately 750 thousand by

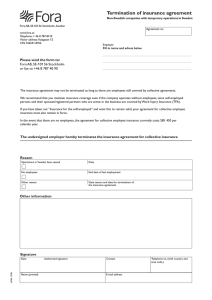

the end of 2010.14 The table below shows the scope of this share of the Dutch labour market.

The Dutch labour market in figures (2010)

Self-employment as a component of the workforce

Total

Employees in large companies

2,000,000

Employees in the public and semi-public sectors

1,000,000

Employees in the SME sector

4,000,000

Business owners in the SME sector

480,000

Freelancers

750,000

Welfare recipients

1,200,000

In recent years, there has been an unmistakable increase in the share of freelancers. In the period

1996-2011, this share increased from 11.7% to 12.9%. These figures indicate that our country has

experienced one of the greatest relative increases in the share of freelancers in Europe in recent

years.15

The SER bases its definition on the criteria that the tax authorities apply when issuing a Declaration of

Employment Status (VAR), which will be discussed later. The SER describes a freelancer as an “a person

who is considered an entrepreneur for tax purposes without personnel”. Aside from the fact that this

definition says very little of substance – even worse, it tends towards circular argumentation – it is so

restricted as to exclude freelancers that are registered as limited partnerships. One of the major

advocates for self-employed workers, the platform for independent entrepreneurs PZO (Platform

Zelfstandig Ondernemers) estimates the share of such “directors/major shareholders” to comprise 10%

of its membership, amounting to about 2000 self-employed people.16 Van Westing, the spokesperson

for the PZO, adds to this the question what is the relevance of the criterion “without personnel”. Is a

self-employed person who experiences modest growth and who hires a single employee no longer

eligible for protection? This question further illustrates the complexity of the criterion for freelancers

within the context of social protection law.

Self-employment and income

Another factor that is at least as important as the proportion of freelancers involves the income that

self-employed workers realise from their freelance activities. These figures do not paint a rosy picture.

More than 40% earn no more than € 10,000 per year, while about 30% earn an average income (or

slightly more). Profits amounting to twice the average income are reserved for the top 10%.17 It is

important to note that these somewhat depressing figures do not reflect the fact that many

entrepreneurs have several irons in the fire in addition to their own companies. Approximately 45%

combine their entrepreneurial activities with paid employment or a pension. These types of

entrepreneurs are known as “hybrids” – partial employees or retirees who are partial freelancers.

The effects of the economic crisis have been particularly harsh for freelancers. Many have had to close

or temporarily discontinue their businesses, waiting to resume them once the economic tide becomes

more favourable. The figures from 2009 reflect this as well. In 2009, the share of freelancers declined

for the first time since 2001, returning to a gradual increase at the end of 2010.18 Director Teulings of

the Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis (CPB) referred to “great hidden suffering” among

freelancers. Their income decreased by an average of 12% in the third quarter of 2009. The loss of

income over all of 2009 amounted to approximately 5%. At the same time, they continued to work the

same number of hours, with the losses largely reflecting a decrease in fees.19 In other words,

freelancers went below the market price in order to avoid going out of business, accepting a temporary

(or not so temporary) loss of income.

These workers should not expect any support from the government in their hidden suffering. They

should not count on such bailout measures as the part-time unemployment insurance that allows

struggling companies to retain their employees in anticipation of better times. On the contrary,

Minister Kamp informed Klaver, a Member of Parliament for GroenLinks, that it is an inherent

characteristic of entrepreneurship that income “breathes along” with the economic climate and that

self-employed people bear primary responsibility for finding solutions to any financial problems

experienced by their businesses.20

Freelancers versus employees

Self-employed people have also penetrated that bastion of organised discussion, the SER. Employers

and employees each relinquished one seat; the employers’ seat was assumed by the PZO, and the

employees’ seat was assumed by the freelancers’ association FNV Zelfstandigen. This did not proceed

in a cordial manner. On the contrary, the advancement of self-employment posed dilemmas for labour

jurisprudence and policymakers as well as for social partners, especially employees’ organisations. The

interests of employees do not always run parallel to those of self-employed people, after all, even if

they are both workers. This became obvious for the first time in the mid-1990s. At that time, the

unions tried to block what they considered unfair competition by including clauses about the pricing of

work performed by freelancers in collective labour agreements. In this way, freelancers lost an

important tool with which to enter as a more attractive source of labour. The Netherlands Competition

Authority (NMA) (and later, the judge) made short work of these determinations. FNV was unable to

provide plausible evidence that these agreements served the interests of employees to such an extent

as to warrant a deviation from the interest of free competition.21 The unions do have a certain amount

of leeway to try to reach agreements regarding situations in which “the deployment of freelancers

could lead to underbidding”, although the extent of this authority is far from clear. I shall set this issue

aside with a brief reference to the SER’s recommendations (Chapter 11) and the Cabinet’s reaction to

these recommendations, which add a degree of nuance to the SER’s standpoint on this component.22

Other collective labour agreements are also being made in which the interests of freelancers were

either exchanged for or subordinated to those of employees. As an example, Linde Gonggrijp, the

spokesperson for FNF-Z (the association for self-employed people), mentions the clause in the

collective labour agreement for the cleaning sector – which has been declared generally binding –

according to which employees are taken over when an object is transferred to another customer.23 For

self-employed people acquiring new projects, either on their own or with a partner spouse, this clause

could mean that they would be forced to take on personnel, thus eliminating the qualification of

“without personnel”. According to Gonggrijp, FNV-Z was taken aback by this regulation, and the union

that had drafted the agreement was apparently unaware of the problems.24 She also considers the

prohibition against re-hiring employees as freelancers within one year of termination as a hindrance

for FNV-Z’s target group, regardless of the relative legitimacy of such conditions from the perspective

of employees. These examples demonstrate the complexity of the relationship between freelancers

and employees. This calls to mind the analogy of a stepdaughter who is made to do all of the work

without receiving any rights in exchange for her efforts.

The social risks of self-employed labour

I shall now return to the social risks of freelancers. The statement that I quoted regarding “breathing

along” with the economic climate illustrates the fact that freelancers run social risks in the operation of

their businesses, in addition to the usual risks assumed by employees. In this regard, van Westing

refers to the risks of entrepreneurs and enterprise. The risk of a recession, as described above, is an

example of an enterprise risk. Other examples include the risk of default (customers paying late or not

at all), solvency risk (expected credit not being extended) and the investment risk (investments yielding

insufficient or no returns). With regard to the first risk, Van Westing notes that governmental

authorities (national and local) especially tend to pay their bills late (or extremely late), thus pushing

small entrepreneurs even closer to the brink. In the US, this risk was one of the driving forces behind

the rise of alternative unions for self-employed people. In our country, the introduction of costcovering notary fees will increase the risk of default for freelancers even further.

Personal risks for entrepreneurs include the risk of poverty in old age (the company not generating

sufficient reserves in order to save for the future), the risk of disability and the risk of death. To a

certain extent, these risks are comparable to the social risks of employees, but this applies only to

some degree, as further consideration makes it clear that the circumstances faced by freelancers are

often more difficult. Lastly, Heeger-Hertter and Koopmans distinguish the transition risk (for

freelancers attempting to go into entrepreneurship after drawing unemployment benefits), the risk of

income shifts, the risk of failure or bankruptcy, and the risk of losing social security rights.25

To address all of these risks in detail would exceed the scope of this lecture. Instead, I would like to

consider two entrepreneurial risks that deserve particular attention: the risks associated with

Declarations of Employment Status and the risk of disability.

Ostensible Self-Employment and the risks associated with Declarations of Employment Status

The risks associated with Declarations of Employment Status affect freelancers operating at the

boundaries between self-employment and employment. This type of worker is known as “ostensibly

self-employed” or a “quasi-employee”. To understand the nature of this risk, we must refer back to the

1990s, when the playing field for social insurance was still reasonably simple. People were either

employed (i.e. working for an employer) or self-employed (i.e. working for multiple customers). In the

first case, the customer was an employer and, in that capacity, obligated to pay employee-insurance

premiums and wage taxes. In the other case, there was no insurance and thus no obligation to pay

premiums, and the worker could claim fiscal facilities for the self-employed. Workers were assigned to

one of these two categories by the tax authorities (for income/wage taxes) and by the Employee

Insurance Agency (UWV) for the employee-insurance premiums.

The expansion of the grey area between entrepreneurship and employment highlighted the need for

rules that would define the relationship between the two more clearly. One such arrangement was the

previously mentioned Declaration of Employment Status (Verklaring Arbeidsrelatie, VAR), which was

introduced in 2001. A Declaration of Employment Status is a prior determination made by the tax

authority concerning the legal status of a person who wishes to offer services as a self-employed

worker. This declaration lets potential customers know that the worker is self-employed and that no

wage taxes or employee-insurance premiums are due. Although this appeared to be a perfect solution,

experience proved otherwise. The legislature failed to state what should occur if the two authorities

were to issue conflicting decisions. For this reason, it was possible for a customer of someone holding

such a declaration to hear from the UWV that employee-insurance premiums were nevertheless due

for the labour that had been purchased. The UWV took such action if its investigation had shown that

the person claiming to be self-employed had worked primarily for a single customer, such that the

customer had “actually” been the person’s employer. In addition to the fact that this was inappropriate

in administrative terms, it was deadly for the self-employed entrepreneur’s market: customers who

experienced such situations were likely to think twice before doing business with someone else holding

such a declaration. The 2004 legislation that extended the legal consequences of the Declaration of

Employment Status brought an end to such legal uncertainty by assigning primacy to the tax

authorities. Once they had issued a Declaration of Employment Status, the UWV was prevented from

imposing its own assessment, and the labour was classified as having taken place outside an

employment relationship.

So, all’s well that ends well? Not exactly. The legal uncertainty that was eliminated concerned only the

customer. The tax authority could rule — up to five years later — that a freelancer’s work history had

nevertheless failed to meet the criteria for self-employment, thus resulting in an obligation to repay

the self-employment deduction. The frequency with which this actually occurs is unknown, as it is

never registered anywhere. The government does not consider this necessary. The Declaration of

Employment Status and the self-employment statement were intended to provide additional certainty

to customers.26 State Secretary Weekers recently informed the Members of Parliament Smeets and

Groot (both of the Dutch Labour Party, PvdA) that the enterprise facilities that could be claimed for

income-tax purposes may be “corrected” if investigation proves that they have been claimed

inappropriately. “The frequency with which this happens to freelancers is not known, as they are

fiscally undefined and usually assumed to go along with entrepreneurship”.27

In his reaction to the SER report ZZP’ers in beeld (“An overview of freelancers”), Minister Kamp notes

that it is up to the freelancers in question to estimate the number of customers they expect to have

and that people holding a Declaration of Employment Status are responsible for reporting any changes

in their situations. The minister acknowledges that, in practice, the Declaration of Employment Status

“is sometimes perceived as definitive”, thus leading to negligence in reporting such changes. Such risks,

however, are the responsibility of the party that appeared to be self-employed but later proved not to

be. The only contribution that these workers can expect from the government in this regard is additional

information.28

ZZP Nederland Spokesperson Marrink feels therefore that the Declaration of Employment Status should

be eliminated. The regulation sends a false signal of legal certainty, which has already duped many

workers who are active in the grey areas.29 This conclusion goes too far for the PZO and the FNV- Z,

although they also acknowledge the tricky character of the regulation.30 For self-employed people who

are active at the boundary between self-employment and employment, the regulation might better be

referred to as the Deception of Employment Status.

Self-employment and disability

One entrepreneurial risk that has been the focus of recent attention is that of long-term disability. The

interest focuses on the private disability insurance (AOV), which is associated with quite a few

problems, according to research by the Financial Markets Authority (AFM). Based on its dossier study,

the AFM concludes that “insurers must still take major steps in order to gain a better focus on the

interests of the customer”. In somewhat less diplomatic terns, Hilhorst states: “The AOV policies are

expensive, and they offer a false sense of security. They are full of fine print and exclusionary clauses.

This amounts to deception for self-employed people who become ill”.31 For the purposes of this lecture,

it is relevant to note that, in the past, social insurance also covered this risk for self-employed people

and that such coverage was discontinued at some point. Why did this occur? And, more importantly,

was it wise? The answer to the first question lies in the parliamentary history, which has been

particularly colourful in this regard.

As you probably know, we have both employee and national insurance. For self-employed people, the

national insurance instrument means that the social risk addressed by the scheme is covered

collectively and according to solidarity of the strong with the weak. This is the case with the AOW (risk

of poverty in old age) and the AWBZ (uninsurable medical risks). For a long time, from 1976 to 1998,

disability was also included in a national insurance scheme under the General Disability Act. At that

time, long-term disability was regarded as a social risk, and not as an individual risk for workers.32 It

was noted of self-employed people in particular that they had covered this risk with private insurance

insufficiently, “although few figures are available on this point”. Moreover, a report by the Council for

Small and Medium Enterprise had shown that the risk of disability was not sufficiently covered by

private insurance.33 The choice for a national insurance scheme instead of, say, an insurance for the

self-employed as advocated by the SER, was motivated by the “red tape and costs” associated with

such separate insurance schemes and the impossibility of achieving a complete system for those who

were already disabled at the time when the scheme would take effect.34

Another arrangement was introduced that occupied the middle ground between the AOW (basic

allowance for residents) and the WAO (calculation of disability payments according to former earning

power). Only married women were excluded from entitlement to benefits, as “the position of married

women in the social security system is arranged in a manner that is quite different from employee

insurance”. This fact was “obviously due to (...) the structure of the first national insurance schemes

from the 1950s”.35 The transitional legislation for the AAW in 1976 was generous, if not limitless. All

residents who had been disabled longer than 52 weeks at the time when the legislation was adopted

were eligible for AAW. Municipalities were subsequently eager to take advantage of the opportunity to

bring their problematic public-assistance cases under this arrangement. It is for this reason that the

AAW became just as much a “success story” as the WAO had been in the 1990s. It was not, however,

the primary reason why the concept of national insurance was ultimately eliminated ten years later. The

AAW stumbled over a combination of the political desire to introduce greater market forces into the

WAO and the fact that the law was based on faulty premises, if not on quicksand.36 I could devote an

entire lecture to this ten-year history of ping-ponging between legislator and judge, but I shall resist this

temptation.37

In 1998, the law was replaced by two categorical arrangements, one of which, the WAZ, is relevant to

our topic. In full, the WAZ provides insurance against the financial consequences of long-term disability

and a benefit scheme in connection with childbirth for self-employed people, partner spouses and other

non-employees with earned income. Several arguments were advanced for sustaining a social

insurance scheme for self-employed people, closely resembling the arguments that had been advanced

some twenty years earlier with the introduction of the AAW. If left to their own devices, self-employed

people would waive their insurance due to considerations related to cost or to an optimistic estimate

of their own risk. Should disability occur in such a situation, its effect would be to shift the costs to the

General Assistance Act. Insurers cannot guarantee that they will be able to offer accessible and

affordable private insurance to all self-employed people. This is because such a plan would involve

individual contracts, the acceptance and premiums for which would be determined largely according to

the insurer’s assessment of individual risk.38

It is also worth noting that the legislature has made every possible effort to prevent groups of nonemployees from falling through the cracks. Directors and major shareholders would fall under the

scope of the WAO, while groups of “non-employees with other earned income” (e.g. home-care

workers, clergy and freelancers without employment contracts) were insured under the WAZ.39 A

government subsidy was provided for the costs of insuring these non-employees, as the Cabinet did

not consider it desirable for self-employed people to be burdened with the additional expenses

associated with this expansion.40 Such considerations were absent from discussions concerning the

transitional law. The point in this context was that people who had previously fallen under the AAW

cases would retain their rights under the old conditions and that these existing cases would also be

funded by the Disability Fund for the self-employed.41

Six years later, another source was tapped. The coalition agreement for the Balkenende II government

announced the elimination of the WAZ “in order to improve the scope of social insurance schemes”.

This improvement was once again dominated by the structural promotion of participation in the labour

market. The measure was legitimised with the observation that it was “essentially possible” to cover the

risks of disability for self-employed people “with private insurance”. Moreover, self-employed people

make a conscious choice for entrepreneurship, along with all of opportunities and risks that it entails.42

Hilhorst’s “grasshopper” argument (note 3 above) was apparently no longer a point for

consideration.

The government was able to get away with this about-face because the WAZ had already become quite

unpopular.43 MKB Nederland (the largest entrepreneurs’ organisation in the Netherlands) felt that the

level of benefits were out of proportion to the premiums to be paid. Moreover, and to the great

irritation of the organisation, the sharp increase in the WAZ fund – which amounted to approximately

€1 billion at the end of 2004 – had not resulted in premium reductions. They had further determined

that the conditions of private insurance policies were often more favourable and that, in some cases,

they were also less expensive.44 The WAZ was attractive, though, to freelancers with below-average

earnings; for self-employed people with annual income of less than € 13,000, the insurance was even

free. The various unions affiliated with the FNV also did not oppose the elimination of the WAZ. They

would nevertheless have preferred to see some discussion of alternatives, such as collective basic

health insurance or public disability insurance without a “tail burden”, which is another term for the

cost of benefits to those previously eligible for the AAW.45

These alternatives received no serious consideration. The government compiled all of the various

objections to the WAZ – no need for compulsory insurance amongst the target group, excessive income

solidarity, disproportionate premium pressure in relation to coverage – into a single argument for

abandoning the principle of social insurance for the self-employed. It was acknowledged, however, that

the elimination of this arrangement could be problematic for certain groups. For this reason,

agreements were made with the Dutch Association of Insurers for a guarantee scheme for selfemployed people who had been denied by an insurer or who were able to obtain insurance only with

medical exclusions or additional premiums. This arrangement appeared simultaneously with legislation

that terminated access to the WAZ. It was amended in 2008, in consultation with the various selfemployment interest groups, the Ministry of Financial Affairs and the Ministry of Social Affairs and

Employment. According to the 2009 legislative evaluation, however, very little use was made of this

scheme.46 To the best of my knowledge, the quality of the guarantee scheme has never been

investigated. For this reason, we can never be certain whether the group for which this product was

intended is acting irresponsibly or whether it is perfectly justified in avoiding it.

The legislation that terminated access to the WAZ also eliminated the public facilities for covering the

risks of pregnancy and childbirth for the self-employed. This measure was reversed several years later,

as the risks of pregnancy and childbirth proved less easily covered by private insurance than had been

estimated before the scheme had been eliminated. Moreover, according to the explanation

accompanying the legislation on pregnancy and childbirth benefits for the self-employed, the absence

of such arrangements would increase the risk that too many women would continue to work up to

delivery and resume working too soon thereafter. This could endanger their own health, as well as that

of their children.47 With respect to this measure the government’s action was perfectly timed. Two

years later, the EC issued a directive requiring Member States to provide at least a certain degree of

social protection for self-employed people with regard to pregnancy and childbirth.48

Attention from the European Union

The latter example brings us to the European Union’s approach to self-employment. Earlier in this

address, I mentioned the 1999 Supiot report that had been commissioned by the European Commission.

The Commission had invited a group of experts to outline the contours of the changing labour

relationships in the various Member States, and to examine the manner in which national and

European labour law should respond to these developments. Seven years after publication of this

report, the theme “Labour and Europe” appeared on the Commission’s agenda once again, this time in

the form of a Green Paper, which is a policy document that could serve as a prelude to legislation. This

document contained an analysis of the challenges facing labour law in the 21st century, and it invited

the Member States and all stakeholders to consider the analysis and some practical issues that were

related to it. The document identified the issue of how labour law could evolve to support the

objectives of the Lisbon Strategy regarding sustainable growth to achieve more and better jobs as the

“central challenge for Europe”. Flexicurity can play an important role in this regard, not as an end in

itself, but a means towards a “fairer, opener and more integration-oriented labour market that

contributes to improved European competitiveness”. A footnote adds that labour law is not the only

relevant factor. A revision of the tax burden may also be necessary in order to create jobs, particularly

low-paid jobs. Further contributions could be achieved by shifting the emphasis from labour taxes to

consumption or pollution.49

In this document, self-employment was approached primarily from the demand side. The Green Paper

described self-employment as an “opportunity to respond flexibly to the need for restructuring, to

reduce the direct and indirect costs of labour and to apply resources more flexibly in response to

unforeseen economic circumstances”. “In many cases”, states the Green Paper, self-employment is a

free choice for suppliers. In exchange for the lesser degree of social protection, self-employed people

gain more direct control over their pay and working conditions.50 The source of this claim is unclear; no

reference is made to statistical support or evidence from research in this regard.

After mentioning the benefits of the various forms of working, the document addresses their social and

societal risks. The Commission addresses these risks only with regard to employment, unless the term

“employee” can be understood to include freelancers and the term “employment” to include project

agreements with self-employed contractors. The Green Paper refers to “an increasing variety of

employment relationships”, ranging from workers who “have become trapped in a succession of shortterm, low-quality jobs” to “atypical contracts that do not result in better-protected employment, even

in the long term”. The analytical portion of the document concludes by noting that the Commission

intends to initiate a debate on the necessity of more flexible regulations in order to “help workers

anticipate and manage change, regardless of whether their contracts are permanent or of an atypical,

temporary nature”.51

Self-employment does re-appear in the concrete questions. Questions 7 and 8 concern the desirability

of clarifying the legal definitions of employment and self-employment (7),52 and the need for a floor of

rights to regulate the working conditions of all workers, regardless of the form of their employment

contracts (8).53

Almost immediately, the Green Paper generated a deluge of criticism from both academics and the

various stakeholders. Professor Silvana Sciarra, who holds the Jean Monet Chair, notes that the Green

Paper “rotates around ‘modernization’, a non-legal concept which leaves space to different approaches

and proposals. The ambivalence of this terminology (…) may cause some interpretative doubts”.54 The

employers’ organisation UNICE expressed its “deep concern” about the message of this document,

which paints an unjustified negative picture of flexible forms of employment and self- employment.

Moreover, it suggests an implicit agenda for the harmonisation of labour law that would come at the

expense of growth and employment and that is at odds with the flexicurity approach.55

The representative body of private employers with a public purpose, CEEP,56 was of the opinion that

the Green Paper posed the right questions but to the wrong actors. The employees’ organisation ETUC

argued that the Commission had addressed only part of the issues that should have been placed on the

agenda, wrongly suggesting that the cause of all problems lies in the fact that standard employment

contracts offer too much protection. Finally, the Platform of European NGOs announced that it was

pleased with the timely consultation on how to address the gaps in the protection of workers and the

establishment of a European social standard. On the other hand, the NGOs denounced the limited

approach of the Green Paper, which ignored many aspects of flexicurity, including infrastructure,

supportive activation policies and investments in lifelong learning. The president of the Platform,

Anne-Sophie Parent, noted that European citizens are concerned about the manner in which Member

States compete with each other by lowering taxes and reducing workers’ rights in order to win

investments. “If the EU does not act on that, it will never regain the confidence of people”.57

The initiative ultimately died a quiet death. The Commission issued a further communication on the

results of the public consultation,58 after which the topic disappeared into a European desk drawer.

The analysis in the Green Paper nevertheless provides a good picture of how the “new” selfemployment was perceived at the European level less than five years ago. In addition, several

publications that appeared in response to this document show that the legal aspects of the grey area

between independent enterprise and employee status can be approached in many different ways.59

Finally, this state of affairs provides an interesting illustration of how self-employment moved from the

spotlight to behind the curtains less than ten years after the Supiot report. The ball is over, and

Cinderella is back in the kitchen. But this obviously does not mean that she has disappeared.

Back to the transition risk

It is time for a brief review. I have attempted to provide some insight into the socio-economic position

of freelancers and other small businesses, as well as the social work-related risks that they may face. I

have also shown that this issue received considerable attention ten years ago, but that this attention

currently appears to have slackened. In his speech on the occasion of the Thirteenth National Labour

Law Dinner, Houweling notes that the conclusion that freelancers are on their own with regard to their

social risks can be contrasted with the fact that freelancers/entrepreneurs enjoy numerous tax

advantages.60 Be that as it may, such benefits do not count until a company has become successful and

thus profitable. As we have seen, for quite a few small independent entrepreneurs this is not the case.

I would like to use the rest of this lecture to make several observations and, in a few cases, specific

recommendations regarding the risks that I have described. I shall begin with the transition risk, or the

case of “starting as a social insurance beneficiary”. My inspiration for this case came from the report by

Hurenkamp, Tonkens and Duyvendak entitled Wat burgers bezielt (“What motivates citizens”).61 In this

report, the authors establish that the government is once again in search of citizens: what motivates

them, what do they need, and how can the government enter a good relationship with them?

Although these questions were raised in the context of volunteering, they are also relevant in relation

to people who display what Hilhorst calls “social resilience”, or the ability to absorb setbacks. Hilhorst

uses this term in relation to such group initiatives as the Bread Fund that he describes. A Bread Fund is a

savings reserve in which freelancers invest money in order reduce their risks collectively, and thus for

themselves as well.62 In this respect, they resemble the medieval guild chests which were early

precursors of social insurance.63 On the other hand, “resilience” can also be a matter of individual

actions, including the exchange of the relative security of social insurance for life as a freelancer. Can

social insurance help to reinforce the resilience of such entrepreneurial people and, if so, what does this

require? I have deliberately chosen to formulate the question in this way, as the treatment that

has befallen both types of starters can more appropriately be described as demotivating than as

motivating. How can this be? And, more importantly, can something be done about it?

For Carla, it was determined that she had to repay much more than she had earned, based on a scheme

for WAO recipients who had not yet recovered, but who had already begun to earn income. In this sort

of situation, the benefit is not repealed or revised, but the earnings are translated into a lower extent of

disability and thus a lower benefit payment. For freelancers, of whom it is usually uncertain whether

they will realise a profit, the benefit payments are tentatively based on the old level, with any profit

figures being used retrospectively to adjust the benefit percentage downwards.64 According to

established jurisprudence, the adjustment for self-employed people is calculated according to the

annual profits accepted by the tax authorities.65 Such calculation could have either favourable or

unfavourable effects. Upon filing the tax return, therefore, Carla or her accountant should have been

aware that there is more at stake than how much income tax she would either be refunded or be

required to pay. Retrospective recovery – which is deemed in most cases inappropriate and therefore

unlawful in many situations – is in fact permissible, as self-employed people report their information

only in retrospect, after the end of the fiscal year. In certain circumstances, retroactive recovery can

still be contrary to legal certainty or other general principles or unwritten rules.66

One nasty side effect is that the recovery takes place on the basis of a gross amount; it was up to Carla

to request a refund of any double tax that had been assessed for and by her. The law allows the UWV

no discretionary space or authority to relax its approach in such cases.67 It is thus quite possible that

the settlement in Carla’s case proceeded according to the rules. Even so, however, this is not the entire

story. First, a good board should be expected to inform any WAO recipient who is considering selfemployment in advance about the possible consequences. In this regard, counselling that amounts to

no more than “report back in a year” would seem to a bit careless, almost as if the freelancer is going

cold turkey. A more fundamental question is whether the legal system is still relevant in contemporary

situations. What if the UWV had warned Carla? Would she have dared to take that step? Or would she

have buried her plan, as it ultimately proved too risky? And what would have happened if that had

indeed been the case? Is it not time to reflect upon the perverse effects on those embarking on the path

of entrepreneurship from within the context of the WAO? I shall set this question aside for a moment

and return to Bertus.

Bertus was fortunate in that his case was not isolated, as with Carla, who had to wage her battle

against the bureaucratic windmill as a lone Don Quixote. Because Bertus represented a great many

“Bertuses”, his case led to an investigation by the National Ombudsman, in addition to many rounds of

parliamentary questioning and, in the words of Fluit and van der Schaft, a “damning report” on the

UWV’s implementation of the starters’ facility.68

I shall again begin with the legal background of the case. The Unemployment Act (WW) of 1985

establishes the general rule that starting to work as a freelancer heralds the end of eligibility for

benefits. This can refer to all benefits or only a part, in cases involving the gradual start-up of a

company. Those wishing to start businesses from within the context of the WW must submit periodic

retrospective reports of the hours they have worked, followed by a proportionate reduction in the

hours used to determine WW benefits. The termination of eligibility is irrevocable; once it has been

suspended, it remains suspended, even if the number of hours of self-employment decreases

thereafter.69 The law does allow for the possibility of renewing the benefits for entrepreneurs who

discontinue their business activities within eighteen months, although this requires the actual

termination of the business.

In the late 1990s, various measures were taken to strengthen the activating character of the social

security scheme. One of these measures involved the introduction of an orientation period in the WW.

During a period of up to six months, there was no obligation to seek employment, thus allowing

prospective freelancers to prepare for entrepreneurship without losing their eligibility for benefits.

Such preparation could include matters such as writing a business plan, registering with the Chamber

of Commerce and arranging for loans and insurance, but not soliciting customers or conducting any

other business activities. This scheme was in effect from 1998 until 2007.

In 2006, a more structural scheme for starters emerged.70 This scheme allowed unemployment

recipients wishing to start their own businesses to be self-employed for up to six months without

affecting their eligibility for benefits. It did require a plausible chance that prospective starters would

be able to support themselves structurally with their companies. During this period, benefits were paid

as an advance, being settled afterwards with 70% of the profits from business. It was not necessary to

specify the number of hours devoted to the company, and activities carried out for the company were

equated with job-application activities.71

Bertus had started under the old scheme, and he had reported the number of hours that he had spent

on his company, although this total was lower than the number of hours he had reported to the tax

authorities in order to claim the self-employed deduction. Was that fraudulent? If he had taken his

case to court, I would not have expected him to have much of a chance of winning, but the National

Ombudsman ruled otherwise. An investigation by the Ombudsman’s office revealed that, during the

period in which Bertus was starting his company, various information leaflets had been in circulation,

thus making the legal playing field extremely opaque. Just how opaque the situation was became

evident through the file comparisons conducted within the context of the investigation. Of all those

who had started businesses under the old system, 42% had committed benefit fraud

The freelance dossier as a wake-up call

As a result of this bizarre outcome, the dossier on the WW and self-employment had political

consequences. In this case, the House of Representatives, which is usually eager to take action

whenever any type of abuse is suspected,72 saw cause to request the Minister of Social Affairs to allow

the UWV additional space in which to waive recovery “in cases of government failure”.73 Honouring

this request would amount to a relaxation of the rules for collection and recovery, which had been

tightened considerably during the 1990s. Unfortunately for the Bertuses and Carlas of the future, the

Minister informed the House of Representatives that he was not amenable to this request. In his view,

the most important lesson from the freelance dossier was that “citizens should be provided with

adequate information, without abandoning the principle that all citizens are responsible for educating

themselves about their rights and obligations”. In addition, the regulations should be such that they

can be applied without the use of discretionary authority. According to the Minister, broad

discretionary powers, such as those requested by the House of Representatives, would threaten the

uniformity of practice.74 This response implied a promise for future regulation: in the future, this would

become clear, unambiguous and easy to interpret and apply. I shall set these ambitious targets aside75

and return to the motivation of citizens.

In this respect, the context of social security requires modesty. As a vehicle for the allocation of public

funds, social security is more of a straitjacket than it is an incentive for daring ideas and

unconventional solutions. It would already be a big step forward if the regulations and their

implementation did not impose excessive obstacles for people like Carla and Bertus. Inspired by these

two real-life examples, however, I can identify several points for improvement for which I would like to

present as recommendations.

A few specific recommendations

My first recommendation concerns the establishment of a public-private advisory and information

service for benefit recipients who are considering the option of entrepreneurship. Although such

offices do currently exist, most have either a public or a private character.76 A public-private

partnership or PPP can bring together the best of both worlds. The office could be located in the

existing job centres and staffed by employees of the Chamber of Commerce, municipality and the UWV

as public parties, along with a representative of an interest group for self-employed people as a private

substantive expert. This office could organise afternoon information sessions in the spirit which the

PZO spokesperson described as follows: “Know who you are and know your abilities”. But also: think

carefully before you take this step. You do not become an entrepreneur overnight, and

entrepreneurship is not for everyone. In this respect as well, the expertise of an organisation of selfemployed people could help in assessing both the commercial and personal chances of survival for the

company.

The office would also be intended for annual or semi-annual progress conferences. In these

conferences, the operating results of the previous period (twelve or six months) could be discussed

and, if applicable, the relative wisdom of continuing or stopping. Afterwards, and this is my second

suggestion, the agreements on such matters as extending the trial period and the repayment of

benefits received could be recorded in writing and signed by both parties. This trial period could be –

this is my third suggestion – extended twice for a maximum of eighteen months. This would be

equivalent to the irrevocability period in the WW. The starting point for the discussions would be an

approach based on high trust and the acknowledgement that starters are faced with many issues in the

initial period and that they are not intending to swindle anybody. During the initial period, it will

therefore be necessary to overlook more than in later stages, when people have become familiar with

the way things work. And yes, this does indeed imply that the UWV should have more discretionary

power, just like that which has already been allowed to municipalities for years now. Especially for the

Minister of Social Affairs, I add that discretionary power does not necessarily lead to arbitrariness, and

that letting go of uniformity in social security can also be thought of as customisation. To those who

are afraid of wasting public money, I would say that not always recovering every last euro can also be

seen as an investment in a new business and thus in moving out of public assistance. There are

undoubtedly several snags – for example, when such terms as “investment” and “unfair competition

risks” are used. With clear delineation and a solid foundation, however, these problems can be

resolved.

Reprise: illness and disability risk

My second set of recommendations concerns a social risk that is considered the most problematic risk

associated with freelancing: that of debilitating illness and long-term disability. From my argument, it

should be clear that the label of “freelancer” is too indefinite for general statements. The same holds

for such terms as “new” or “small” self-employed people. This explains why some advocates of

freelancers consider certain government interventions as commandments, while others are equally

resolute in rejecting them. It also explains why, according to the statement of the PZO, the majority of

its members have no desire for state-organized social insurance, even as a growing group of

freelancers are organising themselves in archaic and substantively vulnerable Bread Funds. This fact is

consistent with the findings of Dekker. Dekker interviewed about 40 freelancers – 25 in the IT sector

and 15 in the construction sector – and found that there was indeed a base of support for collective

coverage against illness, disability and age. There was considerably less enthusiasm for collective

unemployment insurance. Indeed, according to the respondents, considerably less money should be

used for this purpose.77 Finally, the multiplicity of the target group can explain the nuanced

recommendations of the SER on this point. Nuance, however, is not the same as division: the SER

managed to herd all of the cats and reach a unanimous recommendation. On a less positive note, this

unanimity was achieved by introducing a working definition that is suitable for separating the

employee sheep from the goats that fall outside of the employee-insurance rolls, but which says

nothing about an individual’s social or socio-economic position. Such information is a crucial element

for research or statements concerning the base of support for or the desirability of collective

arrangements. Because, although we may tend to overlook this aspect in our unified and egalitarian

welfare state, social insurance thrives best in fairly homogeneous collectives.

For this reason, I would advocate a fresh reconsideration of the combination freelancing and social

disability insurance, eight years after the WAZ fiasco. I was inspired to make this recommendation by

the programme Goudzoekers (“Prospectors”) that was broadcast by VPRO last summer. Allow me to

present the last case study for this afternoon.

Gerard was 43 years old and worked in the construction industry. Five years earlier, he had discovered

that he could exploit his abilities more fully by not working for one boss, but according to project

contracts for multiple companies. The business prospered, Gerard had a profitable company and he

was enjoying prosperous times. Then the recession struck. In October, he and many of his colleagues

were informed that there would be no more contracts after 1 January. Gerard did what many of the

previously mentioned freelancers in “hidden suffering” do: he tightened his belt and drew on his

reserves. Approaching the municipality for temporary support was not an option, as he was self-

employed. The only way that he could qualify for assistance would be to go out of business, and he was

not yet ready to take such a step. At one point, he cancelled his disability insurance, as he needed the

money to live on. Three months later, Gerard had a heart attack. You can fill in the rest.

This case shows that the arguments that were advanced 60 years ago, when the post-war employee

insurance schemes were being designed, are no less relevant today. However understandable it may

be under such circumstances, society should not allow people like Gerard the freedom to cancel their

insurance, at least not as long as our social system maintains such a binary structure. You are X and

therefore not Y; if you are Y, you can no longer be X.

Does this amount to a plea for returning to the WAZ? Absolutely not. From the outset, the WAZ was an

historical mistake, and it is not surprising that no self-employed person – and not even the relevant

interest groups – would like to return to that law. The insurance was unnecessarily expensive, as the

principals in the self-employment system were not involved in the premiums, while those premiums

were moreover used to pay for benefits for people who had nothing to do with Gerard and his

counterparts. And the scheme was inadequate, as it was designed according to principles that have

little or no relationship to self-employment. That was already the case under the classic regime of the

ZW and the WAO, and it became even worse with the discovery that employers are responsible for

reintegration, the ZW was eliminated and the waiting time for disability benefits was extended to two

years. By that time, self-employed people like Gerard would have used up all of their reserves and be

bankrupt. Self-employed people need another product that would be better suited to their position as

well as their social and occupational risks. My guess is that if we were to succeed in developing such a

product, the willingness to invest in such a scheme would increase rapidly.

The question whether such an arrangement will ever materialise is obviously up to the politicians. In

the 2009 policy brief entitled Zelfstandig ondernemerschap (“Independent enterprise”), the

government identifies as the “underlying rationality of policy” the fact that self-employed

entrepreneurs require no inequality compensation.78 This is not a good omen, although I would not

label an arrangement that does what is needed in this respect as inequality compensation, but as the

facilitation of professional solidarity. Instead of advancing even more substantive arguments, I would

like to take you to the year 2016, when I will give a lecture on a new social insurance scheme that will

take force in the next year.

Freelancers and social insurance, a beckoning prospect

Ladies and gentlemen, next year, the Exit and Reintegration Act for Self-employed Workers (WURZA)

will go into effect for the construction and technology sectors. This arrangement is an experiment; if it

proves successful, it will be extended to the care and commercial haulage sectors. The IT and

consultancy sectors, in which just as many self-employed people are active, have requested in great

numbers to be allowed not to take part in this experiment.

Those who would be insured and obligated to pay premiums would be self-employed people – without

personnel or with only a few employees (no more than five) – with an average annual turnover of at

least € 20,000. Starters will be exempt from premiums for the first two years, and self-employed

people with a lower annual turnover can take out a voluntary insurance policy. The premiums will be

levied by the WURZA-Construction department, which will form a separate branch within the UWV.

This department will collect the premiums for the large and medium-sized employers in the

construction industry, for whom a certain degree of commissioning is assumed. The scheme is funded

in accordance with the formula of “50% independent, 50% principal”.

Self-employed people who are unable to work due to illness will report this to one of the three ARBO-Z

services operating within this sector, and they will be assessed within one week. At that time, a dossier

will be opened, which the self-employed person will be responsible for maintaining. Workers who have

not yet recovered after six weeks must take their dossiers and report to the Z benefits office. Depending

on the disability, applicants will receive benefit payments of 70% (complete disability), 50% (two-thirds

disability) or 35% (between one and two-thirds disability) of the average annual turnover over the past

three years. The maximum benefit duration is two years. For the period thereafter, voluntary WIA

insurance can be arranged with the UWV.

In addition to temporary benefit payments, the legislation will offer reintegration programmes for selfemployed people who do not have the option of returning to their previous occupation. This will be

funded by the construction industry’s education and development fund. It will not be necessary to wait

six weeks before starting such a programme. If the self-employed person and the monitoring physician

agree, re-training can begin immediately. A bonus will be awarded to self-employed people or their new

employers for the successful completion of the reintegration programme within the maximum benefit

duration.

You will understand – and I now return to 2011 – that these are just the main points, and that they are

accompanied by several political choices. Nevertheless, I thought it would be a good idea to sketch a

tentative outline of a scheme that would eliminate a substantial portion of the illness risk for small

entrepreneurs without immediately imposing excessive costs. The six-week waiting period and the

limited benefit duration guarantee that people will not make unnecessary use of the arrangements and

that they will not linger in them unnecessarily.

Conclusion

Ladies and gentlemen, I shall now come to my conclusion. A lot is happening in my field. The implosion

of pensions, work according to ability and the never-ending reintegration file are just a few of the

major topics. The topic I have selected for my address today is one about which we hear much less, but

which more than deserves the attention of the law. It a fitting case for the HSI research programme on

changes in the legal order of labour. I plan to keep the small entrepreneur as a focal point within this

domain, and I would like to conclude my story with three propositions.

First, the treatment of small entrepreneurs is duplicitous. On the one hand, they are hailed as the new

heroes. On the other hand, they are met with indifference when they encounter legal barriers or social

risks. Good examples include the case of “starting while receiving social insurance” and the dossier on

the Declaration of Employment Status, which protects the customer and saddles the quasi-employee

with two negatives: none of the benefits, all of the risks.

Second, the realisation that quite a few small entrepreneurs only appear to be self-employed and that,

even if they have chosen this path voluntarily, they encounter a number of uninsurable practical risks,

should once again have a place on the scientific and policy agendas. In other words, freelancing is a

matter not only for the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Innovation, but also for the Ministry of Social

Affairs and Employment. We must take care not to allow the modest demands of a small group to be

drowned out by those who are in a stronger position both numerically and economically.

At the same time – and this is my third proposition – the category of freelancers is insufficiently definite

for generic policy. A more successful alternative to a single collective arrangement would be more

categorical arrangements that would address the need for protection on the part of a majority in the

sector and that would be grounded in the basic principles of social insurance: mandatory participation,

risk solidarity and shared financing. Such arrangements could operate through legislation or through

collective labour agreements – that is less relevant. It is more important that the issue is redeemed

from its present permissive, opportunistic character.

Finally, the title of my address refers to the freelancer as the stepchild of labour law. In fairy tales, a

bright future is in store for stepchildren. But life is not a fairy tale, of course…

Acknowledgements

I have now come to the end of the substantive portion of my address. I should like to close by thanking

several people. I shall begin with the Dean of this faculty. Edgar, thank you for your efforts to retain the

Chair in Social-Insurance Law within this faculty. I am committed to using this Chair to the fullest in

order to ensure that this wonderful field continues to receive the academic and societal interest it

deserves. The second person whom I would like to thank is the head of the Department of Labour Law,

who has ensured that I have the privilege of holding this Chair. Evert, thank you for the trust you have

placed in me, and thank you for our inspiring and occasionally electrifying cooperation. To my

colleagues in the Department of Labour Law and my colleagues in the HSI: I would like to thank you for

the pleasant working environment and collegiality that I have experienced over the years. A special

word of gratitude is in order for Els Sol, who has helped me to grow from a mono-disciplinary into an

interdisciplinary researcher. I would also like to thank Teun, my supervisor and academic advisor from

the very beginning. Teun, thank you for kick-starting my career as a scientist and for continuing to

believe in me and in my potential, even when I did not yet believe in it myself. I will not devote too

many words to the home front today. Anuscka knows how I feel about her, and if she does not, I will

tell her at some other time.

I would also like to mention several people who have contributed to the creation of this speech. Alex

Brenninkmeijer pointed me in the direction of citizen motivation, and Catelene Passchier assisted me

in sharpening the focus of the topic. I am also grateful to the research respondents: Mieke van Westing

of the PZO, Linde Gonggrijp of FNV Zelfstandigen and Johan Marrink of ZZP Nederland. In this regard, I

must obviously also mention Sakina Kodad, the student assistant for Labour Law, who helped me to

gather all the material that I have presented today.

My final words are for those for whom we do it all, our UvA students. Do not allow yourselves to be

fooled by people who say that social-security law is boring or extremely technical. Those who say such

things know the field only from the outside, or their work has caused them to be too involved in it.

Social security poses questions that are of great public interest. With whom do we wish to show

solidarity and with whom do we not? What do we feel that we can expect of people, and why? And

how can we then translate all this into rules that are both fair and easy to implement, and that can be

understood by the citizens who are affected by them?

I have spoken.

Notes

1. Bakker Commission “Naar een toekomst die werkt” [Towards a future that works], Rapport van de

Adviescommissie Arbeidsparticipatie [Report of the advisory committee on labour participation], 2008.

2. H. Bosschenbroek & J. van den Berg, Doel, grondslagen en geschiedenis der sociale verzekeringen in

Nederland [The objective, foundations and history of social insurance in the Netherlands], The Hague,

1952, p. 102.

3. P. Hilhorst, “Het broodfonds” [The bread fund], De Volkskrant, 12 July 2011.

4. Karin Schulze Busschoff, Claudia Schmidt, “Adapting labour law and social security to the needs of

the ‘new self employed’ – comparing European countries and initiatives at EU level”, WZB discussion

paper, December 2007, ISSN nr 1011-9523.

5. From: M.C.M. Aerts, De zelfstandige in het sociaal recht. De verhouding tussen juridische status en

sociaal-economische positie [The self-employed in social law: the relationship between legal status and

socio-economic position] (doctoral dissertation), UvA, 2007, p. 5.

6. A. Supiot (ed.), “Beyond Employment, The transformation of work and the future of labour law in

Europe. Report for the EC”, 1999. Source: Deakin (2002), see Note 7 below.

7. S. Deakin, “The many futures of the contract of employment”. In: J. Conaghan, R.M. Fischl, K. Klare,

Labour law in an era of globalization, Oxford University Press, 2002, p. 177-197.

8. P.H. van der Heijden, “Een nieuwe rechtsorde van de arbeid” [A new legal order for labour], NJB

1997, p. 1837-1844.

9. A. Supiot, Beyond Employment, Oxford University Press 2001, p. 4, 5. Several country reporters have

co-authored this report, including labour-law Professor van der Heijden from our country.

10. A.R. Houweling, “ZZP: wat wil, moet en doet het arbeidsrecht ermee?” [Independent labour: what

is labour law doing about it, what does it aspire to do and what should it do?] AR 2011, 8/9 Katern, p.

6.

11. EC Green Paper, “Modernising labour law to meet the challenges of the 21st century”, Brussels

22.11.2006, COM (2006) 708, p. 8. The Green Paper suggests that the 15% amounts to 31 million and

indicates that the category of “self-employed without employees” constitutes 10% (two thirds of this

31 million).

12. Houweling (2011) with regard to the definitions of CBS, SER and EIM (Enterprise Information

Management).

13. Aerts (2007), p. 7, with regard to a statement of the Platform for Independent Contractors (PZO).

14. “Zzp’ers in beeld” [An overview of freelancers], Recommendation of the Social and Economic

Council of the Netherlands (SER) dated 15 October 2010, SER, 2010/04.

15. F. Dekker, Flexible employment, risk and the welfare state (doctoral dissertation), Ingkamp

Drukkers, Enschede, 2011, Chapter 5.

16. The PZO has about 2000 direct members and 18,000 people who are members through ties to the

affiliated member organizations. The second large organisation, FNV Zelfstandigen, has about 30,000

members. Another example is ZZP Nederland, which began as a helpdesk for freelancers and which has

become a source of information for freelancers, having nearly 18,000 members. These figures overlap

to some extent, however, as many of the self-employed are members of two or all three agencies.

17. SER Recommendations 2010, p. 91.

18. “Flexwerkers weer aan de slag. Herstel van de arbeidsmarkt komt voornamelijk van ‘éénpitters’”

[Flexworkers back on the job. Labour-market recovery largely due to one-person operations]. NRC

Handelsblad dated 9 December 2010.

19. NRC Handelsblad dated 8 December 2010.

20. TK 2010-2011, Appendix 1476, regarding TK 2009-2010, Appendix 1739.

21. Vision document on collective labour agreements (CAO) for self-employed people and the

Competition Act (Mededingingswet) Stcrt 12 December 2007, nr 241, p. 29. District Court of The

Hague, dated 27 October 2010, LJN BO3551.

22. SER Recommendations (2010). Cabinet reaction to the SER recommendations, dated 4 March 2011,

Parliamentary Papers II, 31 311, no. 71, p. 10, 11.

23. Art. 38.3. An employer who acquires an object due to re-contracting (hereinafter contract change)

shall offer employment contracts to all employees who had been working at the object for at least 1.5

years at the time of the contract change, with the exception of…